Judaism in music

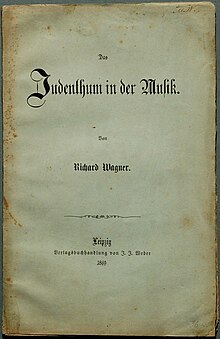

Judaism in Music is an anti-Semitic essay by Richard Wagner , which he wrote in 1850 during his stay in Zurich. On September 3rd and 9th, 1850, he appeared in the " Neue Zeitschrift für Musik " edited by Franz Brendel under the pseudonym K. [Karl] Freiedank. In 1869 Wagner published the article, greatly expanded, as a separate brochure under his name.

Emergence

The essay can be seen as the culmination of a literary feud that began with several reviews of the opera The Prophet by the Jewish composer Giacomo Meyerbeer in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in January 1850, in which the "patriotic Meyerbeer" was accused of a "cosmopolitan musical style". Wagner, who had rated Meyerbeer positively in a letter to his friend Theodor Uhlig dated March 13, 1850, changed his mind under Uhlig's influence.

With his contribution under the pseudonym Freedank, Wagner referred to a previous article that Uhlig had written in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik and commented on the “ Hebrew taste in art ”. Wagner, as he himself writes, considered it necessary to discuss this subject in more detail in order to explain “ what is involuntarily repulsive which the personality and nature of the Jews have for us, in order to justify this instinctive aversion from which we nevertheless clearly recognizing that it is stronger and more prevalent than our conscious zeal to get rid of this aversion. "

The article did not attract much attention at first, with the exception of a protest by eleven professors from the Leipzig Conservatory (today the University of Music and Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy" Leipzig ) to Franz Brendel , the editor of the " Neue Zeitschrift für Musik ", who asked him to resign prompted.

In 1869 Wagner published the article again, as a separate brochure under his own name with a dedication and a short foreword as well as a detailed afterword to Marie von Mouchanoff-Kalergis. In 1860 his concerts in Paris had a deficit of CHF 10,000. covered. Gustav Freytag responded sharply to this brochure and the anti-Semitism it contained in his contribution The dispute over Judaism in music in the magazine Die Grenzboten (1869).

content

After introductory considerations on the supposedly excessive power of the Jews (" ... the 'believer of kings' has become king of believers. ") Wagner describes in his essay "the Jews" as " incapable, due to his external appearance, his language, Least of all through his singing, to make himself known to us artistically ”, that he could“ only repeat ”or“ reproduce ”. " Strange and uncomfortable " is, as Wagner claims, " hissing, shrill, buzzing and muddy phonetic expression " in his speech ; He calls their ritual a " grimace of worship chant in a people's synagogue ", in which " mind and spirit confusing gurgles [], yodels [] and chatter [] " can be found. At the same time, in public conversations with Jews, Wagner stated in her speeches “ cold indifference ” and a “ lack of purely human expression ”. Nonetheless, “the Jew” had come to master public taste in music.

"The Jews could not gain control of this art until what they had to demonstrate in it what they had demonstrably disclosed in it: their inner inability to live."

He criticizes the musical work of Jewish composers of his time. As educated Jews, they strive to strip off the " conspicuous features of their lower fellow believers ". Precisely because of this, however, they are incapable of “ deep, soulful sympathy with a great common striving for something”, the unconscious expression of which the true musician and poet has to interpret. What " the educated Jew " has to say " if he wants to make himself known artistically " can only be " the indifferent and trivial, because his whole drive for art is only a luxurious, unnecessary one ". Wagner particularly goes into Mendelssohn Bartholdy , whom Heine had as early as 1842 ascribed to " lacking naivety ". In his theoretical main work “ Opera and Drama ” from 1852, Wagner expressed the same criticism of Meyerbeer . Jacques Offenbach , the operettas - Composer , however, does not experience any appreciation in his public musical complacency; under “ Jaques O. ” he is only mentioned in passing in one sentence as a complete denunciation of his musical qualities.

In 1850 Wagner wrote the essay with the intention of " still fighting the influence of the Jews on our music with the prospect of success ". When it was re-published in 1869, he saw himself as a victim of an alleged Jewish agitation (he even spoke of a " reverse persecution of Jews "). The pseudonym at the time gave " the enemy the strategic means " to fight against it - Wagner's. With the renewed publication under his own name, he wants to reveal his position to his own supporters. At the same time he addresses the hope that “ only this openness can lead friends in the hostile camp to me and strengthen them to fight for their true emancipation. "

The publication of 1869 drew numerous replicas, such as Joseph Engel , " Richard Wagner, Judaism in Music, a Defense ", 1869, Eduard Maria Oettinger , " Open Billetdoux to Richard Wagner ", Dresden 1869, and Arthur von Truhart , " Open letter to Richard Wagner ”, St. Petersburg 1869. The writer Gustav Freytag accused Wagner in a review of the script:“ In terms of his brochure, he himself appears as the greatest Jew ”.

In principle, Wagner denies Jewish artists any form of originality. They may have mastered their craft with virtuosity, but the result will always be a deception, even a lie, as he explains using Heinrich Heine as an example :

- “I said above that the Jews did not produce a true poet. We must now mention Heinrich Heines here . At the time when Goethe and Schiller wrote poetry with us, we do not know of any poetic Jew: but at the time when poetry became a lie for us, everything possible from our completely unpoetic elements of life, only no true poet wanted to sprout anymore, was there it is the office of a very talented poetical Jew to expose this lie, this bottomless sobriety and Jesuit hypocrisy of our poetry, which is still poetic, with ravishing mockery. He also ruthlessly scourged his famous musical tribal comrades for pretending to be artists; There was no deception in him: the inexorable demon of negating what seemed to be negligible, he was chased forward restlessly, through all the illusions of modern self-deception, to the point where he now lied to the poet again, and his own as well poetic lies put to music by our composers. - He was the conscience of Judaism, just as Judaism is the bad conscience of our modern civilization. "(Pp. 31–32, italics is blocked in the original.)

Ultimately - according to Wagner - the Jews had only one possibility of returning to the circle of civilized humanity: by means of a “work of redemption that regenerates through self-destruction”. As an example of this, Wagner cites Ludwig Börne in the final chord of his pamphlet from 1850 , Heine's antipode:

- “We have to name one more Jew who appeared among us as a writer. From his special position as a Jew, he stepped among us in search of redemption: he did not find her and had to become aware that only with our redemption would he be able to find her into true people . For the Jew, becoming human with us initially means as much as: stop being a Jew. Borne had fulfilled this. But Börne also teaches how this redemption cannot be achieved in comfort and indifferent cold comfort, but that, like us, it costs sweat, distress, fears and abundance of suffering and pain. If you take part ruthlessly in this work of redemption, which regenerates through self-annihilation, we will be united and undifferentiated! But remember that only one thing can be your release from the curse that weighs on you: the release of Ahasver , - the downfall! "(P. 32)

Jens Malte Fischer (see Literature, pp. 85–87) writes about this end: “Starting from this conclusion, there have been many misinterpretations that include the annihilation of European Jewry in the 20th century in the keywords 'downfall' and 'self-destruction' wanted to see preformed. Such an interpretation seems to me to be determined by the consequences of anti-Semitism in the 20th century, at least by the aggravation of the hatred of Jews by the late Wagner, as depicted in the 'Regeneration Writings' of the late period and the often cited statements in Cosima's diaries. However, we are obliged to read the text as it looks towards us from the year 1850. ”Fischer explains that“ annihilation ”and“ redemption ”are basic concepts of Wagner's myth-led fantasy, as exemplified in the Kundry figure in Parsifal represents, an Ahasver figure: “Redemption, dissolution, complete extinction is only promised to her if one day a purest, most blooming man would resist her powerful seduction. [...] she feels that only a man can redeem her in a devastating way ”[Wagner, draft prose for Parsifal , August 1865]. Fischer: “'Annihilation', 'self-destruction' and 'redemption' are not words per se for Wagner that have to do with 'extermination', with murderous intentions. The final passage of Wagner's writing clearly plays with Christian ideas of salvation. [...] The Jews can participate in this process, but they must meet a crucial precondition, by ceasing to be Jews. "His conclusion:" Between the distinct Proto racism of text and pathetisch- apocalyptic cloudiness of the conclusion gapes an insurmountable logical Abyss."

Carl Dahlhaus sees the "poisonous effect" of Wagner's pamphlet in the inhumanity, which consists in the suppression of morality by the philosophy of history :

- “The anti-Semite Wagner does not moralize (and intellectuals may initially tend to credit him with that). He does not reproach Judaism - the allegory, for which the real Jews then have to answer - for being malicious, but instead asserts with a serene, judicial gesture that Judaism is of history - an instance against whose verdict it is there is no appeal - be condemned to wickedness. The hatred masks itself as objectivity; one does not decide for oneself (in order to then take the consequences of the decision on oneself), but lets the world spirit or the law of history speak for itself. "

- “The passages of the pamphlet that, on a cursory reading, appear to be the most abhorrent because resentment is blatantly erupting, such as the caricature of Jewish speaking, are in truth not the worst, although one can imagine that they incited violence. It was not the butchers who carried out anti-Semitism who read Judaism in Music , but intellectuals who were seduced by Wagner's music into adopting miserable philosophemes that they believed connected with the musical work. "

The basic anti-Semitic tone of Wagner's writing was effective until the Nazi era and served Karl Blessinger as the basis for his pamphlet: Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Mahler. Judaism in Music as the Key to 19th Century Music History , published in 1938 and expanded in 1944.

Remarks

- ↑ Matthias Brzoska: Remarks about Meyerbeer's Le Prophète ( Memento of the original from August 10, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , as well as Sabine Henze-Döhring and Sieghart Döhring : Giacomo Meyerbeer. The master of the Grand Opéra. Verlag CH Beck , Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-66003-0 , pp. 147-148.

- ^ Bernt Ture von zur Mühlen: Gustav Freytag. Biography. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2016, page 197f. ISBN 978-3-8353-1890-8 .

- ↑ Published under the title "Richard Wagner's Antisemitism. Repression of Morality through the Philosophy of History", in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, April 19, 1975; Reprinted in: Collected Writings in 10 Volumes , Volume 9, Laaber 2006, p. 365.

literature

- Richard Wagner: The art and the revolution; Judaism in Music; What is German? Edited and commented by Tibor Kneif , Rogner and Bernhard, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-8077-0034-X .

- Jens Malte Fischer: Richard Wagner's ›Judaism in Music‹ . A critical documentary as a contribution to the history of anti-Semitism. Insel, Frankfurt a. M., Leipzig 2000. New edition Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-8260-5844-8 .

- David Conway: Jewry in Music: Entry to the Profession from the Enlightenment to Richard Wagner . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012 ISBN 978-1-107-01538-8 .

- Melanie Kleinschmidt: "The Hebrew Music Taste": Lies and Truthfulness in German-Jewish Music Culture . Cologne / Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2015 ISBN 9783412217792 .

- Jean-Jacques Nattiez : Wagner antisémite: unproblemème historique, sémiologique et esthétique . Paris: Christian Bourgois, 2015 ISBN 978-2-267-02903-1 .