Lathe (psychiatry)

Lathes were a somatotheraptic drug used in psychiatry , particularly in the early half of the 19th century.

Aulus Cornelius Celsus and Avicenna already gave advice to calm the mentally ill by rocking, as did Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein . The Dutch medic Herman Boerhaave also recommended turning the sick person; he is said to have used a swivel chair himself. In the opinion of the psychiatrist Christian Müller, the lathes ultimately served not only for therapy, but also for intimidation and deterrence.

Swivel chairs

The name Cox 'swing goes back to Joseph Mason Cox (1763-1818), who had used it in the Fishponds Private Lunatic Asylum near Stapleton and described it in 1806. It was a chair with a backrest, which was hung with four ropes on the front legs and backrest so that it could rotate, so that the chair was tilted backwards. The patient was strapped into the chair and then both rotated rapidly. As a result, up to 100 revolutions per minute could be achieved; usual were more likely 40 to rare 60. The effect of also Heinroth recommended and used in the "madhouse" of the Würzburg Julius Hospital under Anton Müller lathe on the patient was both nausea -causing dizziness and disorientation, on the other hand, changes in brain blood flow to unconsciousness by occurring centrifugal forces by hanging the chair at an incline and with the patient's head off the axis of rotation . There are both different names of the device (English gyrating chair , rotating swing ; German English swing apparatus ) as well as different constructions.

A similar device used by Erasmus Darwin , the grandfather of Charles Darwin , was called the Darwinian chair (English Darwin's chair or Darwin's machine ). In this device, the chair or cage with the patient is suspended vertically from a crankshaft and is set in rotation by an assistant by cranks.

A swivel chair is also described by William Saunders Hallaran , Ireland, 1818.

Rotary beds

Benjamin Rush , one of the founding fathers of the United States and a pioneer of psychiatry, developed another device, which he called the gyrator or gyrater in 1812 . The exact construction is not entirely clear, but he then describes a possible improvement of the device in which the patient is fixed horizontally on a rotating board. Since the distance between the head and the axis of rotation is much greater, the centrifugal forces that occur would also be correspondingly greater. This construction is often meant when a gyrator is mentioned.

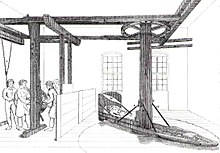

Peter Joseph Schneider reported in 1824: “The lathe, also known as the turning bed, should by no means be missed in well-equipped madhouses, even if this indispensable machine is quite expensive. It can be viewed both as a perfectly comfortable place to rest and as a bed that rotates horizontally on its axis. (...) The patient is now attached to the lathe in such a way that his feet are turned towards the center of the machine, but the head is directed outwards, in a horizontal position of the whole body or also in a sizing position, rotated in rapid oscillations around the axis becomes. This rotating bed is now set in motion by a lever, which is pulled by three to four assistants, so that forty to sixty revolutions of the machine occur in one minute, depending on whether the movements must be faster or slower. "

An acceleration force of 4 to 5 G was achieved in the area of the head . According to Schneider, such a lathe had been in the insane asylum associated with the Royal Charité Hospital in Berlin at the instigation of Ernst Horn since 1807 . Schneider named the effect: “In very many of them there is dizziness, nausea, choking, violent vomiting.” In 1818, Horn wrote: “A healthy individual who is exposed to the effects of this machine can no longer bear the extremely unpleasant feeling for a few minutes is brought about by this peculiar movement. "

See also

literature

- Richard Noll: Article circulating swing and Gyrator in: The encyclopedia of schizophrenia and the psychotic disorders. Facts on File, New York 1992, ISBN 0-8160-2240-2

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Christian Müller : The turning machines in the history of psychiatry. In: Gesnerus: Swiss Journal of the history of medicine and sciences. 55th year 1998, issue 1–2, pages 17 to 32

- ↑ Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein: Novum medicinae genus nimirum vim centrifugum ad morbos sanandos applicatam more geometrarum proponit. Copenhagen 1765.

- ^ Joseph Mason Cox , Practical Observations on Insanity. 1806

- ^ Nicholas J. Wade , Ulf Norrsell, and A. Presly: Cox's Chair: A Moral and a Medical Mean in the Treatment of Maniacs. In: History of Psychiatry, vol. 16, no. 1, 2005, pp. 73-88.

- ^ Emil Kraepelin : A century of psychiatry. A contribution to the history of human morality. Berlin 1918, p. 59.

- ↑ Magdalena Frühinsfeld: Anton Müller. First insane doctor at the Juliusspital in Würzburg: life and work. A short outline of the history of psychiatry up to Anton Müller. Medical dissertation Würzburg 1991, pp. 9–80 ( Brief outline of the history of psychiatry ) and 81–96 ( History of psychiatry in Würzburg to Anton Müller ), here: pp. 139 f. ( Lathe ).

- ^ Benjamin Rush : Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon the Diseases of the Mind. Philadelphia 1812, pp. 224–226 ( digitized version )

- ^ A b c Peter Joseph Schneider : Draft for a doctrine of remedies against mental illnesses, or remedies in relation to forms of mental illness. Volume 2, 1824, p. 96 ff

- ↑ Viktor Harsch: Centrifuge 'Therapy' for Psychiatric Patients in Germany in the Early 1800s. In: Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, vol. 77, no. 2, 2006, pp. 157-60