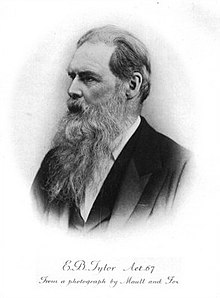

Edward B. Tylor

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (born October 2, 1832 in London , † January 2, 1917 in Wellington , Somerset ) was a British anthropologist , ethnologist and religious scholar . With his most influential work Primitive Culture (1871) he is considered the founder of social anthropology .

Life

Tylor was the fifth child of a wealthy brass caster and came from a Quaker family. This explains his initial interest in the origins of the religion. However, he did not see religion as an expression of a belief, but as an intellectual building. After attending a small Quaker school in Tottenham , he joined his parents' business, since in the 1840s membership of the Anglican Church was a prerequisite for admission to one of the major state church universities.

Tylor acquired his knowledge as an autodidact . He traveled to America and met the archaeologist and anthropologist Henry Christy in Havana . While traveling together to Mexico in 1856, Tylor discovered his interest in anthropology. Back in England he dealt systematically with the history of Mexico and turned particularly to prehistoric research. In 1858 he married Anna Fox, who took an active part in his research. In 1861 Tylor, who lived as a freelance private scholar , published his first work, the travelogue Anahuac: or Mexico and the Mexicans, ancient and modern . The first significant result of his intensive studies was Researches into the Early History of Mankind in 1865 . Tylor gained recognition and has since been considered one of the leading ethnologists of his time.

In 1871 he was accepted into the prestigious Royal Society and in 1883 appointed curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum . In 1884 he was appointed Reader in Anthropology at Oxford University . In 1896 he received the first chair as professor of anthropology at Oxford University, which he held until his retirement in 1909. In 1905 he pushed through that anthropology could also be studied as an independent subject. In 1912 he was raised to the nobility for his services to science.

plant

Tylor's definition of culture shaped anthropology for decades because it is an openly formulated definition and can be adapted at any time to new historical circumstances: “Culture is that complex whole, knowledge, belief, art, morality, law, custom and all other abilities and includes habits that humans have acquired as a member of society. "

Tylor's focus was on the study of mythology , magic and the religion of the so-called " primitives ". Especially in his work Primitive Culture (1871) he showed himself to be a determined evolutionist in the sense of a socio-cultural evolution . He described the development of religion as follows: At the beginning there is the animistic belief (belief in an animated nature), which develops in a second step into polytheism (polytheism), and finally in the last step it changes into monotheism (one-god belief) . He was convinced, however, that remnants of a more primitive way of thinking could still be found in the most advanced cultures. During his six months of field research in Mexico, Tylor coined the term survival ("holdover"). This term describes fragments of old traditions that have been preserved through the historical development of a culture. On the basis of this, the history of the culture can be reconstructed.

Tylor described the matriarchal society in 1896 . He based his studies on the reports published in 1871 by a Dutch colonial official on the Minangkabau in western Sumatra .

For Tylor, the comparison of cultures was the yardstick for determining culture evolution; he created a dynamic picture of this cultural development:

- progress

- Decay

- to survive

- Resurrection

- remodeling

According to Tylor, a culture can theoretically develop in three directions at any point in time:

- progress

- sideways stray

- Regression

Aftermath

Among the ethnologists influenced by Tylor were James George Frazer and later the Viennese School of Cultural History around Wilhelm Schmidt . Like many evolutionists of his time, however, Tylor was also referred to by his critics as an "armchair anthropologist". This term means all those anthropologists of the 19th century who do not base their theories on their own field research, but on reports from missionaries, colonial officials, etc. Among the critics of Tylor were Robert Ranulph Marett and Andrew Lang , who denied that the idea of God was a matter of fact developed animism, and also Edward E. Evans-Pritchard . The term “animism”, coined by Tylor, proved to be particularly long-lived. Due to its central role in Tylor's teaching buildings, it is nowadays avoided as far as possible in religious studies and ethnology.

Works

- Anahuac: or Mexico and the Mexicans, ancient and modern (1861) digitized

- Researches into the Early History of Mankind (1865) Digitized / German research on the prehistory of mankind and the development of civilization. Leipzig 1866 digitized

- Primitive Culture (1871) / dt. The beginnings of culture: Investigations into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom. Leipzig 1873 - Digitized I , II

- Anthropology: an introduction to the study of man and civilization (1881) digitized ; German under the title Introduction to the Study of Anthropology and Civilization . German authorized edition by G. Siebert. Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1883 digitized

literature

- Karl-Heinz Kohl: Edward Burnett Tylor (1832 - 1917) , in: Axel Michaels (ed.): Klassiker der Religionswissenschaft , Verlag CH Beck, Munich 1997, 3rd edition 2010, ISBN 978 3 406 61204 6 , p. 41– 59

Web links

- A Bibliography of Edward Burnett Tylor. From 1861 to 1907

- Literature by and about Edward B. Tylor in the catalog of the German National Library

- Books by and about Edward Burnett Tylor in the catalog of the SUB Göttingen

- EB Tylor at Project Gutenberg (engl.)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Tylor, Edward B. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tylor, Edward Burnett |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British anthropologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 2, 1832 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 2, 1917 |

| Place of death | Wellington (Somerset) |