Ice Cellar Assembly

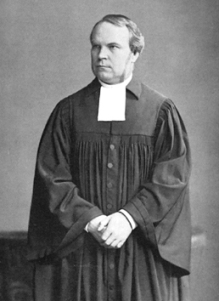

The ice cellar meeting on January 3, 1878 was the unsuccessful first attempt by the anti-Semitic court and cathedral preacher Adolf Stoecker to found a Christian Social Workers' Party as an alternative to social democracy .

prehistory

On December 5, 1877, the Central Association for Social Reform was founded in Berlin on a religious and constitutional-monarchical basis . In addition to Adolf Stoecker, the pastor Rudolf Todt and the economist Adolph Wagner were involved in the establishment. The aim of the association should be to answer the social question religiously and in accordance with the system and thus to counter atheism and the revolutionary aspirations of the social democracy of the time . However, since Stoecker came to the conclusion relatively quickly that the association did not meet his expectations, he invited to a popular assembly on January 3, 1878, just four weeks later, at which a new party was to be founded.

aims

In parts the objectives of the new party were similar to those of the Central Association: The social question should be answered in a Protestant and monarchist way. The means should be reform rather than revolution. But the start-up should achieve more: Stoecker did not want to discuss the social question. The new Christian-Social Workers' Party should rather be the main instrument of his struggle against social democracy, which in his eyes endangered the existence of state and church. He wanted to turn the workers away from social democracy so that they could return to the church and the fatherland. "To oppose the atheistic organization of social democracy with a Christian coalition of workers - that was the task" (Adolf Stoecker)

procedure

On January 3, 1878, the public founding meeting took place in the restaurant “Eiskeller” in a working-class district in the north of Berlin. Stoecker had commissioned his helpers to recruit employees of the Berlin City Mission , supporters of conservative associations and evangelical youth and men's groups in order to secure a following in the audience. Nevertheless, the approximately 1,000 social democratic workers present were in the overwhelming majority, and so they elected one of their ranks, Paul Grottkau , to chair the assembly.

Now Stoecker's supposed trump card appeared: the former social democrat Emil Grüneberg was supposed to advertise in a speech for turning away from social democracy and joining the Christian Social Party. However, his speech was a fiasco: he spoke incoherently and incomprehensibly and was often interrupted by laughter and contradiction.

Stoecker had not originally planned to give a speech himself, but he now spoke spontaneously. In his impromptu speech he presented himself as a man from a humble background and took up some social democratic demands. He then sharply polemicized against the path of the bloody social revolution, against atheism, materialism and hatred of the “fatherland”. He concluded with an advertisement for his program: The socialist principles of freedom, equality and brotherhood all come from the Gospel of Christ .

After Stoecker, the Social Democrat Johann Most took the floor. In his equally spontaneous, passionate counter-speech, he reduced the address of the court preacher to absurdity and carried those present with him. A resolution was then adopted by a large majority “considering that Christianity, which had existed for almost 1900 years, was not able to alleviate the misery, the extreme misery of the vast majority of humanity” and the establishment of a Christian Social Workers' Party was rejected. Grottkau closed the event with three cheers for the Social Democrats, and as they left the hall, the workers' marseilise was sung. Stoecker had suffered a serious setback.

After that

On February 1, 1878, the constitution of the party was carried out in a small meeting closed to the public and with police protection. According to Stoecker, fifty workers were accepted on the founding day, more than half of them Social Democrats.

literature

- Eduard Bernstein (ed.): The history of the Berlin workers' movement. a chapter on the history of German social democracy. First part: From 1848 to the enactment of the Socialist Law . Buchhandlung Vorwärts, Berlin 1907, pp. 349-350

- Günter Brakelmann , Martin Greschat , Werner Jochmann : Protestantism and politics. Work and effect of Adolf Stoecker . Christians, Hamburg 1982 (Hamburg contributions to social and contemporary history, vol. 17), ISBN 3-7672-0725-7

- Grit Koch: Adolf Stoecker 1835-1909. A life between politics and church . Palm & Enke, Erlangen, Jena 1993 (Erlanger Studies, Vol. 101), ISBN 3-7896-0801-7

Remarks

- ↑ The dates are contradictory in the literature. Often it is simply written “a little later”. The date “1. February ”can be found in Greschat's essay in Brakelmann et al .: Protestantism and Politics , p. 28.