Fairchild Channel F

Fairchild Channel F is a video game console from the US manufacturer Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation for connection to a television. It is based on Fairchild's F8 microprocessor system and went on sale in 1976. The console technology has been licensed to numerous European manufacturers. In West Germany alone, with SABA , ITT Schaub-Lorenz and Nordmende , three major manufacturers produced their own variants: SABA Videoplay , ITT Telematch Processor and Nordmende Color TelePlay .

With Fairchild's device, a video game console was the first to have a programmable microprocessor and interchangeable ROM cartridges . Another innovation was added with the joystick for control. However, the performance and the game selection were limited, so that it could not compete with other devices of the same generation - especially with the Atari VCS 2600 - despite a lower price. After the revised version Channel F System II had also failed, Fairchild announced its exit from the video game business in 1979. Fairchild sold all remaining stocks and technical know-how to Zircon International. A total of at least 350,000 consoles were sold.

Many authors agree that Fairchild's little-known console revolutionized the video game industry in technical, economic and cultural terms.

history

1972 saw the appearance of the first video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey . Just two years later, various companies began developing a new generation of consoles. In contrast to the Odyssey, for example, with its hard-wired discrete electronic assemblies, these devices should have a microprocessor and thus be programmable.

The US company Alpex Computer Corporation constructed the first working prototype of this new generation of consoles in 1974. Your device Remote Access Video Entertainment, or Raven for short, was based on the Intel 8080 microprocessor, which was also released in 1974 . A game was no longer implemented using permanently soldered transistors and logic gates , but rather using program instructions that the microprocessor read from a storage medium and processed. For the first time, it was possible to run various games - which will also be created in the future - on one and the same console. Their exchange only required the exchange of the corresponding storage medium. For this, Alpex chose robust read-only memory in the form of electronic EPROM modules that could be installed on plug-in and thus exchangeable circuit boards. The dimensions and costs of such a circuit board were also very much lower compared to the console of the old generation that had to be replaced in its entirety. This conversion from hardware to software opened up completely new opportunities for the marketing of video games.

development

In the search for financially strong licensees, Alpex presented its patented device to the US company Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp. in 1975, along with two games of tennis and hockey. in front. Fairchild showed interest, but insisted on equipping the console with a microprocessor from his own semiconductor division. Fairchild entrusted his engineer Gerald A. Lawson , who already had experience with arcade machines , with the management of a corresponding feasibility study, code-named Stratos . Working with Alpex designers, Lawson and his development team modified the Raven console and replaced Intel's 8080 system with Fairchild's F8 microprocessor chipset . In addition, the keyboard originally intended by Alpex was dropped in favor of a new type of operating device devised by Lawson. This 8-way joystick had significantly more control options than the rotary controls previously used in consoles . A final assessment of the knowledge gained in the Stratos project, which also contained a study of the housing design by Nicholas F. Talesfore, was presented to the company management on November 26, 1975. Also in view of the forecast sales figures that were also presented, Fairchild decided to build the video entertainment system shortly afterwards .

The miniaturization of the electronic components turned out to be one of the major challenges in the transition to production readiness. The construction of a safe and user-friendly changing system for the game boards, begun in early 1976, also represented new technical territory. Just as difficult was the implementation of the joystick proposed by Lawson for everyday use. The designers completed the last work in August 1976 and then patented the device with all its new components. Most of the technical solutions go back to the mechanical engineer Ronald A. Smith, the shape of the console components to the industrial designer Nicholas F. Talesfore. The acceptance test for electromagnetic compatibility by the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was successfully completed in October - a key requirement for the device to be sold in North America.

marketing

Presentation and delivery difficulties

While the development work was still in progress, Fairchild presented its console to the global public in June 1976 at what was then the world's largest consumer electronics show , the Consumer Electronics Show , in Chicago. However, it was a mere display dummy without any functionality, so there was little interest in it. Fairchild's new device first attracted major national attention in July with a report in the high-circulation US newspaper Business Week , which granted the console a pioneering role in the emerging age of microprocessors. The advertising agency Peter Chope and Associates was responsible for the marketing campaign that may have already been started. On their advice, the manufacturer changed the console name to Channel Fun or Channel F. Already at the Third Pennsylvania Hi Fi / Stereo Expo, which took place on October 18 and 19, Fairchild presented its console under the new name. The manufacturer announced the delivery of the first devices for the beginning of November 1976, the suggested retail price should be 149.95 US dollars. After the start of sales, for unknown reasons, only the outer packaging and the games had the new name Channel F. The name plate, however, still identified the console as a video entertainment system ; a fact that would not change later.

An advertising brochure from 1976 to accompany sales offered the console as a “true entertainment system” for all age groups and family members, because the new plug-in module technology offers everyone the right learning or gaming experience. With the also announced monthly plug-in module replenishment - only three different games were available at the start of sales - the home television set would never be boring and the television room would be transformed into a leisure center "in no time at all". The individual and therefore time-consuming acceptance tests of every single console and every single plug-in module prescribed by the FCC made it impossible to deliver the device in the requested quantity. Therefore, only a comparatively small contingent came onto the market for the 1976 Christmas business. The console with its two built-in games tennis and hockey cost US $ 169.95 at the end of 1976 at the US department store chain JC Penney . The separately sold game modules could be acquired from the same provider for 19.95 US dollars.

Licensing business in Europe and video game crash 1977

After the US sales start, which some publications also specify as August 1976, Fairchild presented its new console in Europe. At the end of November 1976, for example, the “Fairchild TV game” could be seen at the electronica technology fair , which took place in Munich.

As one of the first licensees, the Black Forest radio manufacturer SABA announced a version of the console intended for the German market in April 1977. This replica, called SABA Videoplay, was first presented to a larger audience together with eight game modules in August 1977 at the International Radio Exhibition in Berlin. SABA's 1977 product catalog praised the device with its “videocart cassettes” as “the new entertainment system for the whole family” and as “a completely new system for active television”. Because compared to “all games already on the market”, it would have the decisive advantage of being able to be expanded “continuously” with new games. SABA used print media such as the lifestyle magazine Playboy and the children's television magazine Siehste for product advertising . The device was sold by mail order and retail at the end of 1977 and cost around DM 500, the games around DM 50 each. In other European countries, Fairchild's console was sold under the names Barco Challenger (Belgium), Emerson Videoplay (Italy, price at the end of 1978 320,000 Lira ), Dumont Videoplay (Italy) and Luxor Video Entertainment Computer (Sweden). In probably only very limited circulation, the console also appeared in Japan, where - as in North America and - under the name Channel F . Marubeni Housing Equipment Sales offered them in 1977 for 128,000 yen and the modules for 9,800 yen each.

While the licensing business was ramping up in Europe, the US video game market was increasingly flooded with older consoles. Because of the oversupply, many manufacturers had to offer their devices at prices that were sometimes below production costs. In addition to this ruinous price drop, the video game Crash 1977 , a direct competitor for Fairchild's Channel F came on the market at the end of the year with the appearance of the technically superior Atari VCS 2600. Atari's new console was more expensive and at the end of 1977 only had nine game titles, but Atari was able to come up with implementations of popular arcade machines. Although Fairchild had expanded its range of games to a total of 17 titles, the price of their now outdated console fell visibly. JC Penney also lowered its retail price by January 1978 - to $ 99.99. By early 1978, Fairchild had sold around 250,000 units and planned to manufacture another 200,000 consoles in 1978.

Channel F System II and takeover by Zircon International

In view of the intensifying competition, Fairchild revised its console in 1978 to better keep up with the Atari VCS 2600. The Channel F System II received a more elegant housing with plug-in joysticks and more cost-effective electronic assemblies. In June, the new device could be viewed at the Consumer Electronics Show. As part of the advertising offensive that followed in November, the well-known US actor Milton Berle was hired as a brand ambassador to increase sales through humorous newspaper advertisements and TV commercials.

1978 appeared with the ITT Telematch Processor and the Nordmende Color TelePlay μP, two console versions of German licensees, which were based on Fairchild's revised device. In its overall program from 1978/79, ITT Schaub-Lorenz emphasized in the product description that “state-of-the-art microprocessor technology” was used for an “inspiring and varied teaching and entertainment medium”. In its product catalog from 1978/79, the consumer electronics manufacturer Nordmende particularly emphasized the versatility and entertainment value of its console: "Much more than just a gimmick: Nordmende TelePlay μP - with a versatile micro-processor that you can play with and learn while playing" and "If the television program is yawning - insert the TelePlay cassette and it will be exciting on the screen". The ITT Telematch Processor cost around 490 DM at the beginning of 1979, the games 48 DM each. SABA released the SABA Videoplay 2, an updated version of its console, which also contained all the innovations from Fairchild. In other European countries, Ingelen (Telematch Processor, Austria), Luxor (Luxor Video Entertainment Computer, Sweden) and Adam Imports (Adman Grandstand Video Entertainment Computer, 1978, Great Britain) offered license versions of the System II.

The overhauled console, priced between 125 and 150 US dollars, was not accepted by potential buyers in North America, especially during the high-turnover Christmas business in 1978. Fairchild then gave up his involvement in the video console sector in early 1979. The US-based company Zircon International Inc. took over the remaining stocks and all of the technical know-how. According to journalist Benj Edwards, Fairchild had sold around 350,000 consoles by this time. The US magazine Videogaming Illustrated , on the other hand, names 400,000 devices.

Technical details

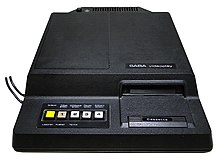

In the front part of the stepped plastic housing there is a slot for the plug-in module and a button panel for controlling the device. The joysticks, which are permanently connected to the device, can be stowed in a coverable housing recess after use. The power supply unit and all electronic components are installed inside the housing.

Main processor, memory and system software

The game console is based on the 8-bit Fairchild 3850 microprocessor . In general, it forms the central component (CPU) of a network of further coordinated circuit components, the F8 microprocessor system. However, due to its deliberately simple architecture, Fairchild's console only contains the read-only memory of the F8 system in addition to the 3850. The CPU of this simplest of all configurations can access an address space of 65536 bytes , which also defines the theoretically possible upper limit of the main memory of 64 kilobytes (KB). The system clock in Fairchild's console is 1.8 MHz , whereas the European PAL versions produced under license are 2 MHz.

In contrast to other contemporary microprocessor systems such as those from Intel or MOS Technology , the communication between the components of Fairchild's F8 system is based on a special technology. This allows the CPU to handle input / output operations in its 40-pin housing and it also contains 64 bytes of RAM ( scratchpad RAM ), which were completely sufficient for many contemporary applications. This means that additional electronic components, such as those for input and output, are no longer necessary, which in turn leads to cost and space savings. However, these advantages were bought at the price of the comparatively demanding programming of the system. In addition to the 64 byte RAM of the CPU, the console has an additional 2 KB video RAM . It serves as a frame buffer for the image content and cannot be used for any other purpose. If the main memory provided by the console is insufficient, additional modules can be retrofitted using appropriately designed plug-in modules. For example, the game Chess produced by SABA contains 2 KB of freely usable working memory in order to be able to increase the depth of the moves calculated by the console.

Immediately after switching on the device, the system software (BIOS) stored in the read-only memory is activated and the console is initialized. If no game module is plugged in, the user can start one of the two built-in games, hockey or tennis, from the keyboard. In cooperation with the BIOS, additional keys allow a game to be paused or extended. The operating system also provides some subroutines that are often required in games, for example for clearing the screen and for simplified memory management. In addition, it also contains character patterns for digits that can be called up by inserted game modules and displayed on the screen.

Graphics and sound generation

The console can display a total of 64 lines of images, each with 128 pixels, on the television. However, it does not make sense to use all of the pixels because the curvature of contemporary picture tubes leads to disruptive distortions in their edge areas. Because of this, the console's system software only supports a smaller display area. For this rectangular section, Fairchild chose the size of 102 horizontal and 58 vertical pixels. One of the eight possible colors can be assigned to each of the pixels, whereby a maximum of four colors can be displayed simultaneously per line. The main processor initially stores the graphic content in the video RAM. The actual television picture is then generated from the data in the video RAM by a graphics module together with a downstream RF modulator . Fairchild's console does not have a highly integrated graphics module like Atari's device with its television interface adapter . Rather, the graphics assembly consists of standard electronic components. The sound generation is just as simple. Only tones in three different frequencies can be played through a loudspeaker built into the console.

Joysticks, control panel and plug-in modules

In his patent specification, Fairchild himself describes the control elements of the console as “hand controllers”, with a movably mounted “joy stick” with an attached triangular control knob embedded in the housing. The plastic rod with the knob mounted on it can be moved in eight directions, in contrast to the knobs on older consoles. In addition, it can be turned about five degrees in two directions, pulled out, but also lowered by applying pressure. Since there is no separate fire button, the possibility of pressing the knob was used instead, for example to shoot balls. The pull function, on the other hand, was often used to start and reset games.

There are two different types of joystick, which differ mainly in the shape of the knob and the shape of the housing. In the revised version, the knob is now square and the housing is more ergonomic in the shape of a pilot's handle.

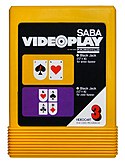

The storage media, also known as cartridges , each contain a circuit board with contact tongues that are protected by a movable plastic shield. The plastic shield also prevents unwanted electrostatic discharge processes when inserting or removing the plug-in module, which can damage the sensitive electronic components of the console and cartridge. If there is a plug-in module in the console, the plastic shielding is at the same time folded to the side by a special mechanism and a conductive connection is established with the electronics inside the console. The microprocessor can thus begin reading out the two read-only memories located on the plug-in module circuit board, each of which has a storage capacity of 1 KB. The board of the game chess is an exception . It contains 6 KB read-only memory and 2 KB work memory together with special control electronics. The design of the yellow plug-in module housing comes from Nicholas F. Talesfore, the sticker was created by the artist Tom Kamifuji.

Games

With the appearance of the console at the end of 1976, three plug-in modules were available in addition to the permanently installed hockey and tennis. Each of the game titles published by Fairchild and the licensees was clearly marked with a sequential number. In total, Fairchild and the successor company Zircon International produced 26 different games. Foreign licensees took over some of the games, but adapted some of them to national requirements or changed the numbering. In addition, in-house developments such as the chess game made by SABA came onto the European market.

List of games released in North America and West Germany

|

reception

Contemporary

Even before the console was released, the American magazine Popular Electronics commented on Fairchild's new device. The ability to load games as a program and thus to change them makes the computer-based console unique. This new concept will set a new trend in the video game industry. It also opens up completely new fields of application for home television, for example through educational games. The imaginable uses are practically unlimited.

With the Video Entertainment System from Fairchild, the "second generation" of devices came onto the video game market, so the impression of Robert M. Bogursky in a scientific study published in 1977. He goes on to say that the microprocessor-controlled console with its ROM plug-in modules revolutionized the world of television games. An unlimited number of game options has become possible for one and the same device. The book author Len Buckwalter also wrote in 1977 that the device would never get boring, as was the case with the consoles without a microprocessor. To better illustrate the readership at the time, he compared Fairchild's console with a record player , where you only need to change the records depending on your taste and interest. In addition to the mostly positive impressions, Buckwalter also names shortcomings: The movement sequences in action-heavy games are "jerky" and the controllers take getting used to. It cannot be controlled with them “with the necessary sensitivity”, as we know from the knobs of the older consoles. In early 1978, John Butterfield named the Fairchild Video Entertainment System in Starlog magazine as the “most spectacular television computer” sold as a “toy”. With Fairchild's console you mutate "all of a sudden" into a "television freak of the next level", because now it is possible to actively intervene in the events shown on the television. Compared to the recently released Atari VCS 2600, Fairchild's device is the "more complex" and "more interesting" system in the eyes of many users.

Retrospective

After Fairchild had given up its involvement in the video game sector, the US American magazine Radio Electronics speculated as early as 1982 that the console could have been widely used without the delays in the FCC acceptance tests. A report in the computer magazine Video Games goes into the already low level of awareness in 1983, with the descriptive title "Channel F: The system that nobody knows". Although it is unknown, it is nevertheless the first device of its kind that was designed for an “infinite supply of new plug-in modules”. Without this development, the latest in video game technology would be unthinkable. In 1983, Fairchild's games were comparatively primitive in audiovisual terms, but some of them could still be captivating, even if the joysticks required to control them were difficult to use due to their many functionalities.

Even decades later, the console is consistently classified as the first of its kind. According to many authors, it has also set further milestones in video game history and culture. However, Fairchild's device is still largely unknown in 2012, which the communication scientist Zach Whalen prominently expresses with the exaggerated phrase "Channel F for Forgotten". In addition to the obvious innovations such as the microprocessor and the exchangeable plug-in modules, the Channel F was the first to pause a game and change game parameters while the system was running. In addition, a player could now compete against the computer - a novelty at that time. Older consoles, for example, would have required a human opponent, according to journalist Benj Edwards in 2016. However, due to the technology that was completely new when it appeared, the console also suffers from defects, as Tim Miller wrote back in 2002: the sound output via the internal loudspeaker is suboptimal, the power switch is located on the back of the device, which is difficult to access, and the joysticks cannot be separated from the console by plug connections. Edwards stated in 2015 that the joysticks, despite their “unique design”, met with little approval from gamers and critics, but that they were completely sufficient for the “simple games of their time”. The non-fiction authors Winnie Forster and Stephan Freundorfer describe the “chic black Channel F-Controller” with their “unusual design” as “multifunctional”, which also makes them “cumbersome” and therefore “takes getting used to”.

In view of the economic historical significance of Fairchild's console noted Edwards that their appearance the development of other consoles with microprocessors like Studio II of RCA Corporation have significantly accelerated and Atari VCS 2600th Whalen sees the main reason for the rapidly decreasing sales success of Fairchild's device in the limited game selection compared to the Atari VCS 2600. Edwards supports this thesis and also states that the manufacturer only brought the device onto the market as a means to an end - for better sales of its semiconductor products. For Atari, however, the "fun factor" has always been the maxim of action. Since Atari, unlike Fairchild, was not tied to a single chip manufacturer, the prices could have been designed much more freely. According to Edwards, the reasons for the poor economic performance of Fairchild's system are primarily to be found with the manufacturer itself.

With the introduction of the microprocessor-controlled generation of game consoles, business based on the razor blade model was also able to establish itself in the video game industry. By selling as many consoles as possible - if necessary, including losses - the manufacturers tried to achieve a high level of market penetration as quickly as possible . The real profit comes from the subsequent high-margin sales of software that can be manufactured and distributed comparatively cheaply, according to Edwards and communications scientist Mark D. Crucea.

Fairchild's console is a permanent exhibit in various computer museums, including the Berlin Computer Game Museum and the California Computer History Museum .

Web links

- Interview with Gerald D. Lawson (English)

- Technical information and programming instructions (English)

- Online emulator with various Channel F games

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Benj Edwards: The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge. Fast Company, January 22, 2015, accessed May 9, 2019.

- ^ Consumer Products Group. Fairchild Annual Report to Employees 1976, April 1977, p. 10.

- ↑ Fairchild Game Okayed. Television Digest, October 25, 1976, p. 11.

- ^ Games - New CES Star. Television Digest, June 21, 1976, p. 13.

- ^ The smart machine revolution: Providing products with brainpower. Business Week, Jul 5, 1976, p. 39.

- ↑ a b c Nicholas F. Talesfore. Fndcollectables.com, accessed May 16, 2019.

- ↑ 3rd Pa. Hi Fi Expo Solid Campus Draw. Billboard, Nov. 5, 1977, p. 71.

- ^ Corporation Affairs. The New York Times, Oct 21, 1976, p. 79.

- ↑ a b Jerry Eimbinder: Home Electronic Game Categories. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Gametronics Conference January 18-20, 1977, CMP Publications, 1977, p. 211.

- ↑ Fairchild Channel F Brochures. Fndcollectables.com, accessed May 16, 2019.

- ↑ Benj Edwards: VC&G Interview: Jerry Lawson, Black Video Game Pioneer. Vintagecomputing.com, February 24, 2009, accessed May 16, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Jerry Eimbinder and Eric Eimbinder: Videogame History. Radio Electronics, July 1982, p. 52.

- ^ Martin Goldberg: Fairchild Channel F. Videogames Hardware Handbook, Imagine Publishing Ltd, ISBN 978-1-78546-239-9 , p. 21.

- ↑ JC Penney advertisement: It's Amazing! Oakland Tribune, Apr. 27, 1977, p. 9.

- ^ Zach Whalen, Channel F for Forgotten. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , p. 63.

- ↑ Jerry Eimbinder: TV Game Background. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Gametronics Conference January 18-20, 1977, CMP Publications, 1977, p. 165.

- ↑ Michael Heysinger: Electronica '76. ELO , February 1977, p. 34 f.

- ↑ Innovation boost in the new color device range from Saba. Funk-Technik, No. 8, April 1977, pp. 146-150.

- ^ Henning Kriebel and Winfried Knobloch: Glotzen-Spiele. ELO , November 1977, p. 36 ff.

- ↑ SABA VIDEOPLAY The new entertainment system for the whole family. SABA complete range 1977, p. 7.

- ↑ SABA VIDEOPLAY The new entertainment system for the whole family. SABA complete range 1977, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Jens Brinkmann and Stephan Freundorfer: Saba Videoplay Werbung # 2. Federal Republic of Pong, April 16, 2010, accessed May 16, 2019.

- ^ Henning Kriebel and Winfried Knobloch: Glotzen-Spiele. ELO , November 1977, p. 36 ff.

- ↑ Antonella Riccio Tabassi: Vetrina - Giocare con la tv. L'Europeo, November 10, 1978, p. 176.

- ↑ William Audureau: Pong et la Mondialisation. Pix'n Love, 2014, ISBN 978-2-918272-78-6 , p. 67.

- ↑ フ ェ ア チ ャ イ ル ド ・ チ ャ ン ネ ル F (丸 紅 住宅 機器 販 売) を 東京 都 江東 江東 区 の お 客 客 様 よ り 買 取 さ せ て 頂 き ま し た. June 3, 2015, accessed July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Advertisement. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ↑ Mirko Ernkvist: Down Many Times, but still Playing the Game Creative Destruction and Industry Crashes in the Early Video Game Industry 1971-1986. History of Insolvency and Bankruptcy, January 2008, pp. 11-16.

- ^ A b Charles WL Hill and Gareth R. Jones: The Home Video Games Industry. Strategic Management - Cases, 8th Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2008, ISBN 978-0-618-89471-0 , pp. C71.

- ^ Fairchild Channel F News Articles / Sales Ads. Fndcollectables.com, accessed May 16, 2019.

- ↑ Now! New low price. JC Penney, January 1978.

- ↑ David Ahl: Random Ramblings. Creative Computing, September / October 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Cutback in Games. Television Digest, Aug 21, 1978, p. 9.

- ↑ The intelligent screen games and the new Tele-Match Processor. ITT complete program 78/79, p. 33.

- ↑ Much more than just a gimmick. Nordmende Programm-Illustrierte 78/79, p. 8.

- ↑ video play. Video, Vereinigte Motor Verlage GmbH, issue 1 from 1979, p. 72 f.

- ↑ SABA VIDEOPLAY 2. SABA complete program 1979, p. 34 f.

- ↑ a b Dieter König: Fairchild Channel F And Relatives Cart List. Classic Consoles Center, accessed May 21, 2019.

- ↑ Sally Peberdy: The marketing of games is high risk business. Financial Times, Nov. 23, 1978, p. 22.

- ^ David H. Ahl: Smart Electronic Games and Video Games. Creative Computing, November / December 1978, p. 74.

- ↑ Programmable video game ... Television Digest, April 2, 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ ABC's. Videogaming Illustrated, October 1982, p. 10.

- ↑ a b Fredric Blåholtz: Schematics. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ↑ Terry Dollhoff: F8. 16-Bit Microprocessor Architecture, Reston, 1979, ISBN 978-0-8359-7001-3 , pp. 70-73.

- ^ Lowell O. Turner: Fairchild Semiconductor. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ↑ Fredric Blåholtz: Homebrew: RAM test. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ Zach Whalen, Channel F for Forgotten. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , p. 65.

- ↑ Sean Riddle: Channel F specs. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ↑ a b Patent application : Cartridge Programmable Video Game Apparatus. Filed August 23, 1976, published June 20, 1978, Applicant: Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corp., Inventor: Ronald A. Smith, Nicholas F. Talesfore.

- ^ Zach Whalen, Channel F for Forgotten. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , pp. 67-69.

- ↑ Jerry Eimbinder: Home Electronic Game Categories. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Gametronics Conference January 18-20, 1977, CMP Publications, 1977, p. 209.

- ↑ a b c Winnie Forster and Stefan Freundorfer: Channel F Hand-Controller. Joysticks, Gameplan, 2004, ISBN 3-00-012183-8 , p. 9.

- ^ Andre Adrian: Fairchild Channel F / Saba Videoplay Chess, 1979? Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ↑ Torsten Othmer: SABA Videoplay - Debut for the plug-in modules. Videospielgeschichten.de, October 10, 2009, accessed on May 16, 2019.

- ↑ Fredric Blåholtz: Gallery. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- ↑ Kris Carrole: Roundup of TV Electronic Games. Popular Electronics, December 1976, p. 36.

- ↑ Robert M. Bogursky: A Home Video Game Cartridge Connector System. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Gametronics Conference January 18-20, 1977, CMP Publications, 1977, p. 89.

- ^ Len Buckwalter: Games with Brains. Video Games, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1977, ISBN 0-448-14345-3 , p. 87.

- ^ Len Buckwalter: Channel F. Video Games, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1977, ISBN 0-448-14345-3 , p. 127.

- ^ John Butterfield: The Computer's Game. Starlog, January 1978, p. 41 f.

- ^ Roger Dionne: Channel F: The System Nobody Knows. Video Games, March 1983, p. 73 f.

- ^ Zach Whalen, Channel F for Forgotten. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , p. 60.

- ↑ Benj Edwards: You wouldn't be able to pause your video games today without Jerry Lawson. Arstechnica.com, February 28, 2016, accessed May 21, 2019.

- ^ Tim Miller: Change the Channel. Ugvm, Issue 3, 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Zach Whalen, Channel F for Forgotten. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , pp. 63 f.

- ^ Mark D. Crucea: The Virtual Hand: Exploring the Societal Impact of Video Game Industry Business Models. Dissertation, December 2011, p. 131 f.