Odyssey (game console)

The Odyssey is a video game console that can be connected to a television; it was the first of its kind. It was developed under the direction of Ralph Baer and produced by Magnavox in a slightly modified form . From September 1972 initially only available in the USA, followed by further international sales areas the following year. In the Federal Republic of Germany, for example, ITT Schaub-Lorenz took over the distribution of the device called Odyssey in 1973 .

In contrast to devices that appeared later, such as the Atari 2600 and Philips G 7000 , the Odyssey console does not have a microprocessor built into it . Simpler integrated circuits with, for example, logic gates are also not used. The entire electronic processing takes place exclusively with the help of discrete components such as transistors and diodes , which means that the performance is very low. The representation on the television is limited to coarse-resolved black and white images; there is no background sound.

After more than 350,000 units had been sold, Magnavox discontinued production in the spring of 1975 in favor of the successor models Odyssey 100 and Odyssey 200. Despite its simplicity, the console, often referred to in retrospect as the Magnavox Odyssey , is considered a revolutionary device: According to many reviewers, it made history in technical, economic and cultural terms.

history

In September 1966, Ralph Henry Baer, who immigrated to the USA, designed an additional device for television for the first time, with the help of which he wanted to make interactive TV games possible for every household. The content to be displayed should be fed into the antenna socket that was built into every television set. In this and in its commercial claim - there were around 40 million televisions in American households in the mid-1960s - Baer's plan differed from other electronically generated games with video display devices. These had already existed in the university environment and in research laboratories since the late 1940s, but were often only accessible to scientific staff and students.

development

The trained television technician Baer presented the first electron tube-based feasibility study of the device to his employer Sanders Associates at the end of 1966. Convinced by the design, the US defense company, which specializes in electronic components, approved funds and personnel for a corresponding development project under Baer's direction shortly thereafter.

First drafts and Brown Box

After starting work in February 1967, Baer and his team of developers, consisting of William L. Harrison and William T. Rusch, were able to present concrete proposals for the games to be implemented as early as May. A first transistor-based prototype ready for demonstration , which also included games for use with a light rifle, was presented to Sanders management in June. After this was found to be good, Baer's development budget was immediately increased.

This was followed by investigations into the structure of the device using various electronic technologies. This included, for example, the use of integrated circuits in diode-transistor and resistor-transistor logic , but also of emitter-coupled gates . Their use turned out to be uneconomical in view of the sales price targeted by Baer of 25 US dollars (today, adjusted for inflation, corresponds to approx. 190 euros) for the finished device. It remained with diode-transistor logic with inexpensive discrete components.

In November 1967, Baer presented an advanced prototype in-house, which for the first time also included a ping-pong game and the associated control dial. Finally, in January 1969, another, largely fully developed prototype, the Brown Box, was ready for demonstration purposes for potential licensees. This device, completely covered with imitation wood foil, contained light gun and chase games as well as some other ping-pong variations. In the meantime, designs with contemporary transistor-transistor logic in the form of integrated circuits of the 74xx series - also in the then novel CMOS technology - had also fallen victim to the cost pressure.

After it was licensed to Magnavox, one of the largest manufacturers of television sets at the time, in January 1971, the further product development of the company's internal 1TL200 device was transferred to the engineers there. The underlying game suggestions and technical solutions developed by Baer, Harrison and Rusch had previously been registered for various patents by Sanders.

Under the direction of George Kent, Magnavox initially made some revisions to the Brown Box to reduce manufacturing costs. So you only took over the knobs from the controllers, but equipped them with an additional button to restart a game. Magnavox planned the light rifle as an optional accessory; a third type of controller developed by Baer's team was omitted entirely, as was the assembly for outputting a colored image background. As an inexpensive replacement for the latter, colored foils were introduced instead, which adhered electrostatically to the television screen. Magnavox also dispensed with the game selector on the Brown Box in favor of six wire bridge cards. The games themselves were essentially designed by Baer, Harrison and Rusch. Ron Bradford and Steve Lehner expanded and combined these with additional elements such as playing cards, play money and dice, which were later included with every console. In addition to the technology and the games, Magnavox also revised the visual appearance. The device and the coordinated controller were given futuristic-looking housings made of two-tone plastic. By May 1971, the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) had its electromagnetic compatibility approved - a key requirement for the device to be sold in the USA.

marketing

In order to evaluate the acceptance among potential buyers and thus the market opportunities, demonstration samples with the name Skill-O-Vision were first exhibited in various US cities. Probably because of the similar sounding Smell-O-Vision, a design for odor-accompanied television by Michael Todd , Magnavox changed the name of its device to Odyssey after the successful marketing tests. The new name probably goes back to Stanley Kubrick's popular 2001 film : A Space Odyssey . In May 1972 Magnavox had familiarized all its dealers with the console and on May 22nd informed the public at a press conference in New York. A little later, production of the 100,000 devices planned for 1972 began in Tennessee, USA. According to Baers, the manufacturing costs were between 40 and 50 US dollars per console.

Market launch and advertising campaign

The console was only available from Magnavox specialist dealers in the USA from September 1972 at a price of US $ 99.95 (today, adjusted for inflation, corresponds to approx. EUR 610). In addition to the device with its two controllers, the scope of delivery included six wire bridge cards, an antenna splitter, six batteries and accessories for the games. A power supply, the light gun controller and other games were optionally available.

The launch was accompanied by a nationwide advertising campaign. In addition to classic print advertising in the form of newspaper advertisements, glossy brochures, cardboard displays and the like, Magnavox also used radio broadcasts on radio and television. It praised the console as "a new dimension in television" and as the "game of the future". The entire family can participate in television and are no longer just a viewer. The “electronic game simulator” is particularly suitable for children for “entertaining learning” of numbers and letters and for expanding their knowledge of geography.

The ubiquitous advertising did not fail to have its effect - many retailers sold out the devices within a short time. Surprised by the sales figures, Magnavox increased its production output. However, interest in buying slackened unexpectedly and sales slumped towards the end of the year. The sales figures for 1972 - the figures fluctuate between 69,000 and around 100,000 units - were thus well below the 140,000 devices forecast by Magnavox and already pre-produced. According to Baer, Magnavox then considered withdrawing from the video game business in 1973, an idea that was discarded only a little later because sales had picked up again in the meantime.

Worldwide sales

In 1973 Magnavox began to develop additional markets, especially in Europe. At the international radio exhibition in West Berlin, for example, the regional distributor ITT Schaub-Lorenz presented a version intended for the German market for the first time. This device, known as the Odyssey , was then available in stores for around DM 400 (adjusted for inflation today would be around EUR 610). The product was advertised on the packaging and in print media as an "electronic television game for the whole family". The slogan "The fourth program" used in advertisements emphasized in particular the use of domestic television, which is now independent of public broadcasting, and its possible transformation "into a football stadium, a tennis court, a shooting range or even space".

The console was also available in other Western European countries, including France and Italy. In addition, from 1973 onwards, some manufacturers in Europe also offered unlicensed replicas such as the Spanish Overkal . These clones were technically largely identical, but differed in their optical design from the original. Outside Europe and the USA, the Odyssey console could be purchased in Mexico and Brazil, among others. In 1974, Nintendo, which had previously only appeared as a supplier of the light rifle controller, took over further sales for Japan .

From autumn 1973, Magnavox - meanwhile economically stricken by poor sales in its television division - granted a 50 percent discount on its console if the buyer purchased a television set at the same time. In total, Magnavox was able to sell around 89,000 consoles in 1973. In the following year the manufacturer intensified the advertising measures and brought out a revised version of its device with improved ball control and revised clubs. In addition, Magnavox, which had been hostile to Philips in October, changed its marketing policy at Christmas time and from then on accepted sales by the US mail order company Sears . In 1974, depending on the source, a total of 129,000 or 150,000 consoles were sold. It is believed that the US alone accounted for around 90,000 units.

Cessation of production and successor models

In May 1975, according to Baer, Magnavox stopped production after around 350,000 devices - but significantly more are also possible. Production of the successor models Odyssey 100 and Odyssey 200 had already started in spring .

Games

Due to the strong simplifications in both the presentation and the game mechanics, the pong- like games that can be generated by the console are among the simplest possible video games. They are not directly comparable with the later published and much more complex games of modern game consoles or computers.

Base game and variations

The base game of the console is table tennis , an implementation of the table tennis of the same name. The happening is shown in a highly simplified plan view. All four graphic objects that can be generated by the console electronics are used. Two square points of light on the screen symbolize the two clubs. The ball is also shown as a square point of light, its dimensions being slightly smaller than those of the racket. The net appears in the form of a continuous but ball-permeable center line, which only serves to separate the two halves of the playing field.

After the ball has been activated by pressing the start button, it moves in a straight line across the screen. The player in whose direction the ball is moving must now move his racket using the controller on the screen in such a way that the ball is touched. The direction of flight of the ball is reversed, and now it is up to the opponent to return the ball - and so on. If, on the other hand, the ball is missed, it can be thrown in again using the start button and another rally begins. In order to make the game more varied, the attacking player can influence the ball further. This cutting causes an additional change in the direction of movement of the ball up or down on the screen.

In addition to cutting the ball, its speed and thus the degree of difficulty can also be set using a corresponding rotary control on the console before the game begins. A score display and an acoustic background of the event are not available due to the lack of technical capabilities of the console.

Different arrangements of the four graphic objects can be used to simulate other highly abstract field sports such as soccer and volleyball. The visualization is supported by overlay foils which, for example, mark the boundaries of the playing field. Before the game started, the players had to place these transparent, partially colored plastic films on the picture tube of the switched-on television. The thickness of the foils was dimensioned in such a way that they adhered to the picture tube through electrostatic attraction.

In addition to the sports games, Magnavox also offered games of skill, luck, learning and strategy. In addition to the overlayer, these games were often accompanied by other non-electronic material such as game boards, chips and cards. In many cases, the console only acted to support the game.

Light gun games

The games for use with the light rifle are based on the principle of clay pigeon shooting . The dummy target to be hit is shown on the screen as a white square on a black background. One of the two players uses his control panel to move this pixel across the screen at a specified speed. The other player has to aim at this object with a light gun and "shoot" it by pressing the trigger. In contrast to real shooting, no projectile is emitted by the rifle. Rather, a light-sensitive photocell at the rear end of the gun barrel is used to check whether the bright image point and the gun barrel form a straight line at the time of the trigger. If this condition is not met, not enough light will reach the photocell from the pixel. As a result, it does not provide an evaluation signal for the console electronics and the light spot on the screen is not deleted.

Overview of the games

In the United States, the Odyssey console came with twelve games, compared to only ten for export devices. With the appearance of the console, six more games could be purchased in the USA for 5.95 US dollars each (today, adjusted for inflation, corresponds to approx. 40 euros) and the light gun controller with four associated games for 24.95 US dollars. In the following year a few more titles were added. ITT Schaub-Lorenz took over the game distribution in the Federal Republic of Germany.

Technical information

Control unit

In the front part of the stepped plastic housing of the “play center” there is the slot (“play program slot”) for the wire bridge cards (“plug-in boards”). When you plug it in, the desired game is set and the console is switched on at the same time. Accordingly, the device is switched off again by removing the card. The connections for the two plug-in, wired controllers ("game consoles") are on the back, as are some controls and the sockets for connecting the optional power supply unit and the light rifle. All electronic components and the battery compartment, which is accessible via a flap in the bottom of the housing, are housed inside the housing. The first version of the console produced consists of around 300 individual parts.

The device contains a large base board on which all electronic and mechanical assemblies are accommodated except for the battery compartment. The individual electronic assemblies are located on smaller, pluggable boards, the modules. There are multiple identical modules for similar functions. The differences required for the game functions are implemented by means of appropriate wiring on the base board. In order to shield against electromagnetic interference radiation, the assemblies for providing the high-frequency antenna signal are housed in a metal housing. There are no integrated circuits such as logic gates, microprocessors or memory modules on the circuit boards. Only standard electronic components are used.

The Odyssey console is designed for battery operation to make handling easy and safe for children. Through the use of energy-saving components with exclusively discrete electronic components, the total current consumption could be limited to 15 mA, which enables an operating time of more than 100 hours.

Game consoles, wire bridge cards and accessories

Two identical wired controllers, the "consoles", are provided for operation. They are each connected to the back of the console using a 12-pin connector. In each controller there are two rotary controls ("adjusters") for the horizontal and vertical movement of the "screen figure", another to influence the ball trajectory and the "start button" to start a game.

The numbered jumper plugs are "preprogrammed" for each game, i. H. the silver contact tongues are physically connected to one another in a very specific and unchangeable manner in the black housing. The 44-pin contact spring strip on the base board is used to accommodate the plugs and thus to connect the required functional groups. According to the manufacturer, this type of switching between different games is particularly easy and fast. In addition, there is greater flexibility for possible later expansions to additional play options.

An antenna cable and a TV switch box were included in the scope of delivery for connection to the television at home. In addition to complying with the US radio interference suppression regulations, the latter also enabled convenient switching between antenna reception and console operation.

functionality

In addition to realizing the course of the game, the console must also generate the electrical signals for the television picture. This must be done in accordance with the technical specifications for the analog tube televisions used exclusively in the 1970s . This includes, for example, that an image is made up of lines and that 50 images are to be output per second. This ensures that motion sequences appear as fluid as possible for the viewer and that still images appear largely flicker-free.

The electronic signal processing, which is based on diode-transistor logic, takes place in different function groups, each located on its own circuit board. The most important are the two sync pulse generators, the four screen figure generators (also known as light spot or video generators), the ball flip-flops and the high-frequency transmitter and modulator for the antenna signal. In addition to the passive components, each of the functional groups consists of a maximum of four transistors.

Synch pulse generators

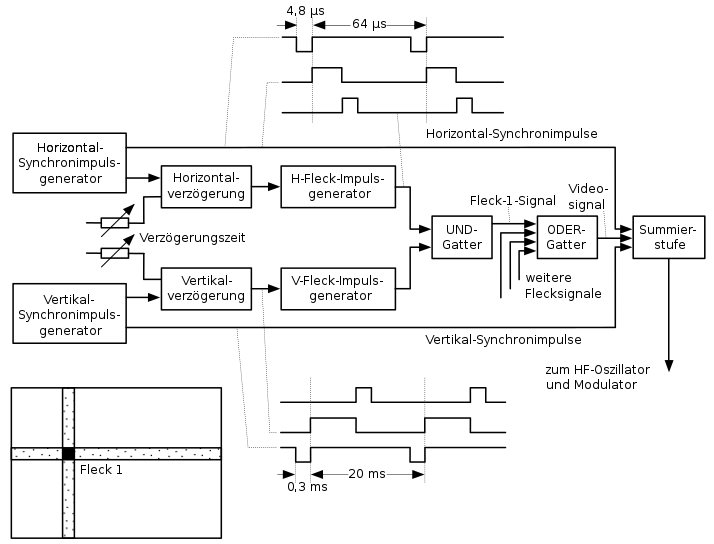

To build up the picture, the television needs the appropriate control signals, the horizontal and vertical sync pulses, for changing lines and pictures . They are provided by the generators for vertical and horizontal synchronization. In terms of circuitry, these are constructed identically and each contain astable multivibrators . The generators only differ in the dimensioning of their components in order to be able to generate the different pulse repetition frequency and pulse width for the horizontal and vertical synchronization.

Screen figure generators, ball flip-flops and gate matrix

To display the four graphic objects bat, ball and center line, corresponding image data are required for the television set. Similar to the synchronous signals, these are electrical impulses, which are also called light pulse impulses. Their generation is based on the use of delay circuits and subsequent logical links between the generated signals. These four screen figure generators are identical in terms of their circuitry. Their behavior essentially only depends on the control voltages supplied: The distance between a racket and the left and top of the screen is determined, for example, by the values of two voltages that are proportional to the resistance values of the potentiometers built into the associated controller, the console . The width and height of the graphic objects cannot be changed.

The position and movement of the ball is controlled by the voltage of an RC element : while the capacitor is charging, the ball moves from right to left. On the other hand, if it discharges, the direction of movement is reversed. The speed of the ball is determined by the adjustable resistance of the RC element, which is accessible to the players on the back of the housing. If the positions of the ball and a club are the same, the direction of the ball is reversed, which, depending on the game, is controlled by up to two other ball flip-flops and the gate matrix. The names are derived from the underlying electronic circuit of the RS flip-flop or a combination of logic gates.

Summing stage and modulator

The synchronizing signals (horizontal and vertical synchronizing pulses) are combined with the image data generated by the generators, the (luminous) spot signals, in a further assembly, the summing stage, to form the BAS television signal . Then, with the help of a high-frequency modulator and an antenna cable, it is fed into the antenna socket of the television set.

reception

Contemporary

As early as April 1972, before Magnavox's official presentation, the New York Times reported the planned manufacture of an "electronic apparatus" for television sets that "simulates" various types of sport. In May 1972, Time Magazine described the Odyssey console as an "in-house transmitter" that was "as complex as a black and white television." The player uses it to control "movable luminous squares" that are "projected onto the screen". The Time magazine went on to say that it is essential for some of the included games on fast reactions are required, on other concentration and coordination. The contribution summed up that the "gaming pleasure" is suitable for all ages, but will be "not cheap". In June 1972, the popular science magazine New Scientist briefly and concisely characterized the Odyssey console as a "very ingenious game" - the television can now be used for more than just watching radio programs.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, too, in 1972 the then high-circulation magazine Funkschau informed about the appearance of the device which "projects a playing surface ... onto the screen on an unused [television] channel". After the Odyssey was presented at the International Consumer Electronics Fair in 1973, the news magazine Der Spiegel reported that the "new [] electronic [] TV accessories from America" are making the television the "family play center". The radio show wrote that "the program makers of the television companies ... [will] have to make an effort, because in the future dissatisfied people will be able to convert their screen at home into a playing field where the family can be active". "Concentration and appropriate reaction" are required of the players, according to the radio show . In particular, the operation of the console requires “some skill”, as Radio TV Phono Praxis noted. In addition, according to the magazine Funk-Technik, “completely new game ideas” and “interesting learning games” can be implemented with the console at the “standard broadcast price”.

The American linguist Michael Z. Newman noted in 2018 that the description of the then novel Odyssey system and other game consoles in the press using vocabulary from television technology was typical.

Retrospective

Even after production was discontinued, many authors referred to the Odyssey console as the “founder” of the home video game industry. Even at a later point in time, publications of various kinds largely agreed that the Odyssey system, the first of all commercial video game consoles, is the "forefather" and "the original console of all video game systems for the home". The magazine Elektronikpraxis went even further and called the device a “milestone in the history of electronics” in 2012 , the media scientist Stefan Höltgen approved a “revolutionary concept” in 2012 and Newman also described the console in 2018 as a link between the era of traditional board games and that of electronic games. The non-fiction author Leonard Herman added in 2012 that Odyssey was the first home video game console, but not the first video game. This honor goes to the arcade machine Computer Space from 1971.

According to the non-fiction author David H. Ahl, the performance of the Odyssey console did not come close to that of the Pong arcade machine, which was also released in 1972 , which is why he described the console as "comparatively primitive" and out of date in 1976. Newman agreed with this assessment in 2018 and added that most Odyssey games could not have been realized with just the "electronic component" alone. Due to the lack of a "processor (let alone a [it] microprocessor [s])" and "memory" functions such as counting the score and using it against a human opponent were not even possible, according to Höltgen in 2012 in a demarcation of the Odyssey Console from computer games. Computer scientist Guy W. Lecky-Thompson said in 2007 that the Odyssey system was overpriced for its poor performance. This placed him in the ratings of Ahl in 1976 and those of Radio Electronics magazine in 1982 as “tight” perceived price as the majority opinion of earlier newspaper reports.

With the general considerations on economic performance that followed in the early 1980s, the manufacturer's sales policy increasingly came into focus. According to the unanimous opinion, the exclusive sale only by Magnavox authorized dealers and the initially ambiguous advertising would have led many interested parties to assume that the device only works with Magnavox televisions. These “marketing errors” would have significantly reduced the chances of success of the “revolutionary” device. Baer shared these assessments in 1983 and came to the conclusion that the economic success "on balance ... was not particularly [great]". The fact that the Odyssey console did not turn out to be a losing business was due not least to Atari's Pong machine, without which it would “have been over pretty quickly”. The sales of the Odyssey console, as the only alternative to the expensive pong machine, would have benefited greatly from the popularity of the arcade machine, according to Herman 2012. The journalist Winnie Forster noted in 2009 that the "arcade scene celebrates Atari's electronic games [e] “, While the Odyssey console could not have“ cracked ”the“ broad mass market ”. For Magnavox, the “first living room video game was not a flop, but also not an overwhelming success”.

According to David Kalat, a more productive source of income for Magnavox was the licensing business with the patents going back to Baer and his employees. The one with Atari is cited as a prominent example. Its founder, Nolan Bushnell , had attended a presentation of the Odyssey system by Magnavox in May 1972 and had an improved version developed and marketed under the name Pong . In a court proceeding brought about by Magnavox and Sanders, a settlement was reached , as a result of which Atari subsequently licensed the necessary patents from Magnavox. Further licensing by other manufacturers such as General Instrument with their AY-3-8500 , which was later produced by the millions, followed, according to Baer. In 1985 the level of inventiveness and thus the legality of the patents was confirmed to Nintendo . According to Baer, revenue from the licensing business is said to have amounted to approximately 100 million US dollars. In addition to the "entry of lawyers into the game business" as formulated by Forster, the idea that came up with the Odyssey console to use the home television for games led to a video game industry that in 2015 reached over 90 billion US dollars, according to the non-fiction author Marty Goldberg implemented.

The Odyssey console and the Brown Box were or are exhibits in various museums around the world, including the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, the Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum in Paderborn, the Computer Games Museum in Berlin and the Pixel Museum in Schiltigheim, Alsace.

literature

- Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press , 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 .

- Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 .

Web links

- Demonstration of the brown box and table tennis by their designers Ralph Baer and William T. Rusch (video, English)

- TV commercial from 1972 (video, English)

- Technical documents of the manufacturer (English)

- Odyemu emulator for Windows operating systems

- Odysim Simulator and lots of information about the Odyssey

Notes and individual references

- ↑ Born as Rudolph Heinrich Baer in Pirmasens .

- ↑ a b Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 14.

- ^ A b c Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 143.

- ^ Tristan Donovan: Replay - The History of Video Games. Yellow Ant, 1st edition, 2010, ISBN 978-0-9565072-0-4 , pp. 7-13.

- ↑ Brookhaven National Laboratory: The First Video Game?

- ↑ a b Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 30.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 144.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 145.

- ^ Ralph Baer: Television Games - Their Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, Vol. CE-23, No. 4, November 1977, p. 498.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 146.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 147.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 148.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 6.

- ↑ a b Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 58.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 150.

- ^ A b c d Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 151.

- ^ A b Harold Goldberg: All Your Base Are Belong to Us: How Fifty Years of Videogames Conquered Pop Culture. Three Rivers Press, ISBN 978-0-307-46355-5 , 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ a b c Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 73.

- ^ Walter H. Buchsbaum and Robert Mauro: Electronic Games. McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-008721-0 , 1979, p. 30.

- ↑ Peter Ross Range: Space Age Pinball Machines. Lakeland Ledger, Sept. 15, 1974, p. 7D.

- ↑ a b c Kate Willaert: Pixels In Print (Part 2): Advertising Odyssey - The First Home Video Game. The Video Game History Foundation, May 20, 2020, accessed June 29, 2020.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 91.

- ↑ Brian J. Wardyga: Video Games Textbook. CRC Press, 2018, ISBN 978-0-8153-9089-3 , p. 5 f.

- ↑ a b Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds Volume I: 1971 - 1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , pp. 152 f.

- ^ A b c Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 153.

- ^ Steven L. Kent: The Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press, ISAN, 0761536433, 2001, p. 54.

- ^ Wilhelm Roth: TV screen now also playing field. Funk-Technik, No. 17, 1973, p. 626.

- ↑ a b Elektro Konsumgüter Magazin. Radio TV Phono Praxis, September 1973, p. 33.

- ↑ Tom Werneck : Renner of the season. In: The time. 17th December 1976.

- ↑ Products. Der Spiegel, September 10, 1973, p. 176.

- ^ ITT advertisement: The fourth program. Funkschau, issue 25, December 6, 1974, p. 3105.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 90.

- ↑ a b c David Winter: Magnavox Odyssey. Pong-Story.com, accessed June 29, 2020.

- ^ Lisa McCoy: Career Launcher Video Games. Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7982-7 , 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ a b Jerry Eimbinder: TV Game Background. In: Proceedings of the First Annual Gametronics Conference January 18-20, 1977, CMP Publications, 1977, p. 161.

- ^ Magnavox - The magnificient gift for the entire family. The Tuscaloosa News, December 23, 1973, p. 13A.

- ↑ a b c d e Alexander Smith: 1TL200: A Magnavox Odyssey. They Create Worlds, November 16, 2015, accessed June 29, 2020.

- ↑ How to be a superstar - just play ball on TV. Rome News-Tribune, October 25, 1974, p. 19.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 76.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 7.

- ↑ Industry. Funkschau, Issue 11, May 23, 1975, p. 33.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 180.

- ^ Mark JP Wolf and Bernard Perron: Basic Elements of Video Game Theory. P. 14.

- ^ Michael Z. Newman: Ball-and-Paddles Games. In: Matthew Thomas Payne, Nina B. Huntemann (Ed.): How to Play Video Games. New York University Press, 2019, ISBN 978-1-4798-2798-5 , p. 209. (books.google.de)

- ↑ a b c d e f g Günther Bleß: Odyssey - electronic games on the screen. Funkschau, August 31, 1973, pp. 667-670.

- ↑ Demonstration of the Brown Box and table tennis by their designers Ralph Baer and William T. Rusch (English)

- ^ A b c Michael Z. Newman: Atari Age: The Emergence of Video Games in America. MIT Press, 1st edition, ISBN 978-0-262-53611-0 , 2018, pp. 95 f.

- ↑ Alexander Smith: They Create Worlds. Volume I: 1971-1982. CRC Press, New York, 1st edition, 2020, ISBN 978-1-138-38992-2 , p. 152.

- ↑ Brett Weiss: Classic Home Video Games. McFarland & Company, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7864-6938-3 , pp. 247-253.

- ↑ a b Magnavox: Odyssey rules of the game. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Magnavox: Odyssey Installation and Game Rules (Export version). Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ↑ Operating instructions for various games from Magnavox. Archive.org, accessed June 30, 2020.

- ^ David Winter: The extra games of the Odyssey. Pong-Story.com, accessed July 2, 2020.

- ↑ a b c d ITT Schaub Lorenz: The game package. Funkschau, issue 25, December 5, 1975, p. 120.

- ↑ a b c d G. Bless: "Odyssey", an electronic game simulator. Funk-Technik, No. 24, December 1973, pp. 928-933.

- ^ Otto Limann and Horst Pelka: Television technology without ballast. Franzis-Verlag GmbH, Munich, 1991, 16th edition, ISBN 3-7723-5722-9 , pp. 23-30.

- ↑ Technical documents of the manufacturer (English)

- ↑ G. Bless: "Odyssey", an electronic game simulator. Funk-Technik, No. 24, December 1973, p. 928.

- ↑ G. Bless: "Odyssey", an electronic game simulator. Funk-Technik, No. 24, December 1973, p. 929.

- ^ Home Games Use TV. New York Times, April 29, 1972, p. 43.

- ^ Modern Living: Screen Games. Time Magazine, May 22, 1972, p. 82.

- ^ Gary Pownall: Game, set and match. New Scientist, June 8, 1972, p. 584.

- ↑ Additional television device enables games. Funk-Technik, issue 13, July 1972, p. 664.

- ↑ Products. Der Spiegel, September 10, 1973, p. 176.

- ^ Günther Bleß: Odyssey - electronic games on the screen. Funkschau, issue 18, August 31, 1973, p. 667 f.

- ^ Wilhelm Roth: TV screen now also playing field. Funk-Technik, issue 17, September 1973, p. 626.

- ^ Michael Z. Newman: Atari Age: The Emergence of Video Games in America. MIT Press, 1st edition, ISBN 978-0-262-53611-0 , 2018, p. 52.

- ↑ Kris Carrole: Roundup of TV Electronic Games. Popular Electronics, December 1976, p. 32.

- ^ Len Buckwalter: The New Playing Field. Video Games, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1977, ISBN 0-448-14345-3 , p. 11.

- ^ Danny Goodman: Magnavox Odyssey. Radio Electronics, July 1982, p. 55.

- ^ Mark D. Crucea: The Virtual Hand: Exploring the Societal Impact of Video Game Industry Business Models. Dissertation, December 2011, p. 130.

- Jump up ↑ Raiders of the Lost Consoles - More than an old piece of plastic. Spiegel.de, April 17, 2008, accessed on July 19, 2020.

- ↑ Thomas Kuther: 1972 - The first video game console. Elektronik-Praxis, January 24, 2012, accessed July 2, 2020.

- ↑ Stefan Höltgen: There has been backfire for 40 years. Heise.de, July 1, 2012, accessed on July 2, 2020.

- ↑ Leonhard Herman: Ball-and-Paddles Consoles. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , pp. 53 f.

- ^ David Ahl: Odyssey Video Games. Creative Computing Magazine, November / December 1976, p. 24.

- ↑ Stefan Höltgen : There has been backfire for 40 years. Heise.de, accessed on July 2, 2020.

- ↑ Guy W. Lecky-Thompson: Video Game Design Revealed. Charles River Media, 2007, ISBN 978-1-58450-562-4 , p. 83.

- ^ David Ahl: Odyssey Video Games. Creative Computing Magazine, November / December 1976, p. 24.

- ^ Danny Goodman: Magnavox Odyssey. Radio Electronics, July 1982, p. 55.

- ↑ Videogames… Which Are Best. The Times-News, November 26, 1981, p. 5.

- ↑ Jerry Eimbinder and Eric Eimbinder: Videogame History. Radio Electronics, July 1982, p. 50.

- ↑ George Sullivan: Screen Play: The Story of Video Games. Frederick Warne & Co., ISBN 0-7232-6254-3 , 1983, p. 23.

- ↑ Leonhard Herman: Ball-and-Paddles Consoles. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , p. 54.

- ↑ Steve Bloom: Video Games Interview: Ralph Baer. Video Games, February 1983, p. 81.

- ↑ Leonhard Herman: Ball-and-Paddles Consoles. In: Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Edited by Mark J. P. Wolf. Wayne State University Press, Detroit 2012, ISBN 978-0-8143-3450-8 , p. 55.

- ↑ Winnie Forster: Game consoles and home computers 1972-2009. Gameplan, 2009, ISBN 978-3-00-024658-6 , p. 14.

- ↑ a b David Kalat: The Case of the Video Game Lawsuit Racket.

- ^ David Winter: The story of the Telstar systems. Pong-Story.com, accessed July 27, 2020.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 4.

- ↑ Winnie Forster: Game consoles and home computers 1972-2009. Gameplan, 2009, ISBN 978-3-00-024658-6 , p. 15.

- ^ Martin Goldberg: Magnavox Odyssey - Gaming Started Here. Videogames Hardware Handbook, Imagine Publishing Ltd, ISBN 978-1-78546-239-9 , p. 15.

- ↑ Ralph Baer: Ralph H. Baer.Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Ralph H. Baer: Videogames in the Beginning. 1st edition. Rolenta Press, 2005, ISBN 0-9643848-1-7 , p. 15.