Spiritual warfare

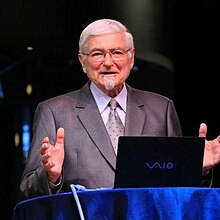

Spiritual warfare ( spiritual warfare ) is a religious concept in the late 1980s in the "third wave" of neucharismatischen movement was developed. Internationally, this concept is particularly associated with the name of Charles Peter Wagner . One of the main representatives of spiritual warfare in German-speaking countries is Wolfhard Margies, founder and senior pastor of the Free Church “Congregation on the Way” in Berlin. In the meantime the term “warfare” is no longer used often, but the concept as such is still behind many actions and prayer initiatives from the neo-Charismatic spectrum.

The concept

Spiritual warfare advocates assume that demonic powers (so-called territorial spirits and powers) rule certain geographic regions. Before the people who live there can be reached with the gospel , the demons must first be defeated. Sometimes this is paired with the idea of being able to exert a direct influence on social and political developments through spiritual warfare; z. For example, the initiative “Intercession in Germany” is of the opinion that, through its intervention in 1988, it reversed the negative trend in German population development. The fall of the Berlin Wall is seen by some groups as a success of spiritual warfare. The defensive variant of spiritual warfare is about protecting cities through “spiritual border patrols”. The “Wächterruf” initiative is organizing a network with the aim of “uninterrupted prayer coverage” in Germany.

methodology

Charles Peter Wagner developed a method of spiritual warfare that can be learned and that involves six steps:

- The area is selected. For a large area (e.g. "40/70 window" between the 40th and 70th parallel north) prayer armies are raised.

- The participants create unity with one another, especially the pastors as “spiritual gatekeepers” of a place must unite.

- Building on this, the various Christian communities should also unite in a region for the purpose of spiritual warfare .

- The prayers prepare for the upcoming spiritual battle through personal sanctification .

- Christians with prophetic talent locate and identify the demons to be found in this area ( spiritual mapping ). As their fortresses z. B. Locates places with pagan or Nazi history.

- Practical prayer fight, specifically as a prayer march: The believers proclaim God's power and order the demons to give way.

Basic theological motifs

According to Peter Zimmerling, there are three basic motifs that are characteristic of the concept of spiritual warfare. Although battles with demons are known from various figures in church history, such as the Desert Fathers , this is something new:

- The whole charismatic movement assumes that demons could influence the fate of people. What is special, however, is that territorial spirits and powers are identified for states, cities, population groups, etc. One imagines that Satan's realm is hierarchically structured.

- Spiritual mapping draws practical consequences from this demonology . So Wagner could z. B. explain why only a few evangelical Christians lived in Guadalajara, Mexico : he identified a marble compass rose, which was set into the ground in a public square, as the “throne of Satan”, from where he ruled Guadalajara.

- Spiritual warfare includes acts of reconciliation between peoples. According to the concept of spiritual warfare , if “fortresses” are not captured, this can be due to the fact that demonic powers are bound to this place through unpunished guilt. Acts of penance are intended to break the curse of guilt. In this way Wagner felt empowered to redeem the sins of the American nation against Japan through vicarious penance.

Prayer Movements and Spiritual Warfare

The understanding of prayer in spiritual warfare (areas could be covered by prayer and spiritual powers driven out) is widespread without the militant vocabulary. "Many prayer initiatives promise social changes through the spiritual conquest of the forces that cause 'evil' (eg homosexuality , abortion , also pluralism and humanism ) and an 'in-existence prayer' of the order willed by God."

Jesus marches

Wagner's prayer movement got an impetus from the “ outdoor intercession ”, which has been practiced in charismatic circles in Great Britain since the late 1980s: “There are all kinds of prayers for a city, regional, national, international prayer hikes and marches, even worldwide 'Jesus marches' take place. ”The purpose of a Jesus march is to conquer a land for Jesus. Anti-divine powers would be disempowered in the region touched by the march, and God would have space to manifest himself there. Associated with this is an act of penance in which the participants ask for forgiveness for the sins of the fathers.

The “March for Jesus” movement achieved public fame through two confessional marches organized around the world in 1994 (according to press reports, a total of 10 million participants) and 1996 (12 million participants); in Germany they took place in Berlin.

Marches of life

The TOS Services e. V. in Tübingen run “ marches of life ” all over Europe : descendants of Nazi perpetrators confess the guilt of their ancestors, descendants of Nazi victims forgive them. Several Protestant regional churches (North Church, Hessen-Nassau and Kurhessen-Waldeck, Bavaria) as well as the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising advise their communities against participating.

"Ultimately, it is about the neopentekostale idea of 'spiritual warfare' ( spiritual warfare ), a high affinity has about on activities, certain areas 'freizubeten' where many Muslims live, as these areas by Islam than by demonic powers haunted are understood. ”The steps of spiritual warfare according to Wagner are also recognizable in the concept of the“ marches for life ”.

Political component

In countries with larger Pentecostal populations, spiritual warfare can be a mobilization strategy to advance a political agenda.

Take the Philippines as an example: here spiritual warfare is often mentioned in connection with political actors oriented towards US interests, but it doesn't have to be that way. Butch Conde, founder of the mega-church Bread of Life , combined spiritual warfare in the 1980s with the fight against the large US military bases in the Philippines. The church founder Wilde Estrada Almeda ( Jesus Miracle Crusade ) tried in 2000 to intervene non-violently with twelve other "prayer warriors" when Abu Sayyaf was taken hostage (so-called Talipao Peace Mission ). The exact circumstances of the hostage release and the role of a military special task force are unclear. Jesus Miracle Crusade spreads the version that the "prayer warriors" freed the hostages without violence.

The author Bartholomäus Grill described the spiritual warfare in connection with the conflict in Nigeria as “Christian Jihad ” and sees the aggressive Christian mission as a cause of the escalation of the civil war. In a Christian fundamentalist strategy paper called AD 2000 and beyond , the so-called 10/40 window between the tenth and fortieth degree of latitude, i.e. the core areas of Islam, was declared as a “satanic bulwark” and “spiritual battlefield of the 21st century”.

In São Paulo, the largest city in Brazil, the annual Jesus marches are a tradition. In June 2019, over a million people attended, including President Jair Bolsonaro .

reception

The Manila Manifesto (1989) of the Lausanne movement adopted the concept of spiritual warfare in Part 5 (“God the Evangelist”) : “Every evangelization involves a spiritual warfare with the principalities and powers of evil ) in which only spiritual weapons can triumph. First of all, these are the Word and the Spirit along with prayer. That is why we call on all Christians to stand up faithfully in their prayers for the renewal of the church and for the evangelization of the world. Every true conversion involves a battle of powers against which the superior authority of Jesus Christ is demonstrated ( a power encounter, in which the superior authority of Jesus Christ is demonstrated ). "

criticism

Spiritual warfare is controversial within the charismatic movement . Wolfram Kopfermann , one of the most important representatives of this movement in Germany, accused the representatives of this concept of a subjective, experience-based pragmatism . The Bible is losing its meaning as a corrective.

When the American organization Global Harvest Ministries called in 2001 for prayer struggle against the "Queen of Heaven", a demon that supposedly the "40/70 Window" dominant (even the Catholics revered Queen of Heaven Mary was one of their masks), distanced the evangelical network German Evangelical Alliance and declared that no groups would be supported that wanted to bring about a spiritual awakening with "territorial warfare". These are "unbiblical methods."

The Evangelical Lutheran side ( VELKD ) named the following points of criticism, among others: The idea of territorial spirits and powers is unbiblical. This is all the more true of the idea that evil spirits are banished to one place through unpunished guilt. "The aggressive attitude and the presumption of being able to take up the fight with evil with or even instead of Christ contradict the spirit of the gospel." A guilt connection between peoples is a complex phenomenon with historical, biographical and psychological aspects, but not supernatural reality that can be erased with an act of penance and thus also put out of the world.

In a similar way, the Baptist theologian Andrea Strübind criticized the principle of "territorial warfare": the underlying demonology exempts believers from seeking rational solutions to conflicts. The sovereignty of God is called into question if, for example, territories are to be conquered for God through Jesus marches so that he can “set himself free” there.

literature

- Matthias Pöhlmann , Christine Jahn (Ed. On behalf of the VELKD ): Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 2015, pp. 231–233.

- Peter Zimmerling : The charismatic movements: theology, spirituality, stimulating conversation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2nd ed., Göttingen 2002, pp. 351-360.

- Wolfram Kopfermann : Power without a mandate. Why I do not participate in "spiritual warfare" . C - & - P-Verlag, Emmelsbüll 1994. ( Review: p. 209ff. )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 43.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 381.

- ↑ Wolfhard Margies, pastor of the parish on the way. In: Aufbruch Verlag, community on the way. Retrieved July 17, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 231.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 352.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 353.

- ↑ a b c Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 232.

- ^ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 354 f. Handbook of world views, religious communities, free churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 232.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 359.

- ^ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 384.

- ↑ Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 233.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 362.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 369.

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 366.

- ↑ Hanna Lehming, Commissioner for Christian-Jewish Dialogue of the Northern Church: Declaration on the planned “March of Life” through Northern Germany in April and May 2015. (PDF) 2014, accessed on July 16, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Center Oekumene, Evangelical Church in Hesse and Nassau, Evangelical Church of Kurhessen-Waldeck: Center Oekumene / page 1 of 8EvangelischeKircheinHessenundNassauEvangelischeKirchofKurhessen-Waldeck Statement on the initiative “March of Life” - Center Oekumene. (PDF) In: http://www.zentrum-oekumene.de/ . 2015, accessed July 16, 2019 .

- ↑ For an appropriate commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the death marches and the liberation of the concentration camps. (PDF) In: www.christen-juden.de. January 27, 2015, accessed July 16, 2019 .

- ^ Giovanni Maltese: Pentecostalism, Politics and Society in the Philippines , Ergon-Verlag, Baden-Baden 2017, p. 82 f.

- ^ Giovanni Maltese: Pentecostalism, Politics and Society in the Philippines , Ergon-Verlag, Baden-Baden 2017, p. 132.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ More than a million people march for Jesus in São Paulo. In: pro media magazine. June 28, 2019, accessed July 20, 2019 .

- ^ The Manila Manifesto (authorized German version). In: Lausanne Movement. Retrieved July 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Peter Zimmerling: The charismatic movements , Göttingen 2002, p. 385.

- ↑ German Evangelical Alliance is critical of the prayer initiative against the "Queen of Heaven." Against territorial warfare in prayer. In: The Evangelical Alliance in Germany. September 4, 2001, Retrieved July 18, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 244.

- ↑ Handbook Weltanschauungen, Religious Communities, Free Churches . Gütersloh 2015, p. 243.

- ↑ Andrea Strübind: Notes on the neo-charismatic movement. (PDF) In: Evangelical Central Office for Weltanschauungsfragen Orientations and Reports No. 21 Stuttgart V / 1995 Ecumenical Forum People's Church and Charismatic Movements October 10 - 12, 1994 Documentation of a conference. Evangelical Central Office for Weltanschauungsfragen, pp. 30–42, here pp. 34–36 , accessed on July 18, 2019 .