Hippopotamus William

| Hippopotamus "William" | |

|---|---|

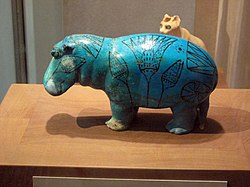

Side view of "William"

|

|

| material | Faience |

| Dimensions | H. 11.2 cm; W. 20 cm; |

| origin | Middle Egypt , Mair , Tomb of Senbi |

| time | Middle Kingdom , 12th Dynasty , approx. 1981–1885 BC Chr. |

| place | New York , Metropolitan Museum of Art , 9/17/1 |

The ancient Egyptian faience - hippopotamus nicknamed "William" is the 12th dynasty dated (circa 1981 to 1885 BC..). The figure has a height of 11.2 cm and is 20 cm long. It belongs to the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) in New York .

Provenance

The faience hippopotamus was found in Senbi's grave in Mair in May 1910 . Its decoration suggests a habitat on the Nile . In 1917 it was given as a gift to the museum by Edward S. Harkness . Bradford Kelleher had a replica designed for the MMA's museum shop , which soon became the museum's unofficial mascot . The nickname "William" goes back to a 1931 article by HM Raleigh in Punch magazine .

"William" became one of the most famous hippopotamus figures and is considered to be one of the most beautiful in the Middle Kingdom .

Description and classification

The "William" called faience from Mair with blue-green glaze shows in black lines on each side and on the head a blossom of the blue lotus flower (Nymphaea caerulea) , framed by two buds; adapted to the shape of the rump, this was provided with the round leaves and the blossom of the white lotus ( Nymphaea lotus ) . The expression of the animal in the figure from Mair is determined in particular by the carved and accentuated eyes and the bulges on the neck.

Faience animal figures are often found grave goods, especially in the late Middle Kingdom. Hippopotamus figures are represented among them and then also a popular grave object in the Second Intermediate Period , with the other animal figures disappearing during this time. The body and head of the hippopotamus figures are consistently designed with a linear-schematic representation of plants or insects, which can be assigned to the humid and swampy habitat of the animal. Several hundred such hippopotamus figures have survived; further examples can be found in the holdings of the Louvre in Paris , in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna or in the Altes Museum , Berlin .

Kunsthistorisches Museum , Vienna

Middle Reich to the Second Intermediate Period

( Altes Museum , Berlin)

meaning

Hippopotamus figures have been documented in Egypt since early dynastic times . During this time they are often found as votive offerings in temples. Representations of hippopotamus hunts in the graves of the old (for example in the mastaba of Ti (around 2340 BC) in Saqqara ) and New Kingdom are interpreted as a reference to an old myth . This is about the ritual overcoming of a monster that was considered a symbol of evil . The hippopotamus is often depicted there with its mouth open, a threatening expression that the faience from Mair completely lacks.

Hippopotamuses also appear in female form: the goddess Taweret was worshiped as an obstetrician in the form of an upright, pregnant hippopotamus, for example.

literature

- Claude Vanderslayen (Ed.): The Ancient Egypt. (= Propylaea Art History [PKG] Volume 15). Berlin 1975; P. 371, color illustration panel L

Web links

- Object description and provenance information from the Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Randy Kennedy: Bradford Kelleher, Creator of Met's Store, Dies at 87 . In: The New York Times of November 6, 2007 (with picture by William).

- ↑ Who is William the Hippo? ( Memento from May 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Metmuseum: FAQ for Kids = The Met's Collection .

- ↑ P. Lacovara, in: Mummies and Magic, The Funerary Arts of Ancient Egypt. Boston 1988, ISBN 0-87846-303-8 , p. 58.

- ↑ Hippopotamus figurine (Inv. E 7709). Louvre website (English / French).

- ↑ G. Dreyer: Elephantine VIII, Der Tempel der Satet. Von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0501-X , p. 74.

- ↑ Claude Vanderslayen (Ed.): The Old Egypt (= Propylaea Art History , Vol. 15. Berlin 1975). Figure 252b, description pp. 288–289; further illustration: Ti on the papyrus boat, hunting hippopotamus. Saqqara. The Mastaba of Ti ( Memento from April 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Claude Vanderslayen (ed.): Das Altegypt, p. 371.