Hop frog

Hopp-Frosch (in the original Hop-Frog; Or, the Eight Chained Ourangoutangs ) is a story by Edgar Allan Poe first published on March 17, 1849 in The Flag of Our Union , which is about the macabre revenge of two disadvantaged people.

action

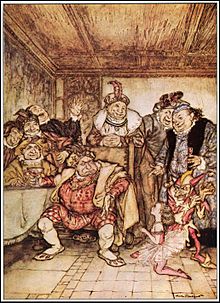

A general gives his king a dwarf who comes from "some barbaric region" that "no one had ever heard of before." The dwarf can only move so sluggishly on his weak legs that the seven ministers of the king give him the nickname Hopp-Frog. As if to compensate, Hopp-Frosch has extremely powerful arms. A girl named Tripetta was part of the general's gift. It comes from the same unknown land, is also petite but graceful, can dance and is pampered by everyone. Linked by their common origins and their small size, Hopp-Frosch and Tripetta become friends. The king, as stout as his fat seven advisors, loves rude jokes and makes Hopp-Frog his fool . When a masked ball is imminent, Hopp-Frosch should recommend a masking method that has never been seen before to him and his seven advisors. When the Hopp-Frog can't think of anything, the king forces the reluctant to drink. When he tries to force a second full wine glass on him, Tripetta humbly asks her to spare her friend, who cannot stand the wine, the agony. Angry at her presumption, the king pours the wine on her face. Now Hopp-Frosch finally comes up with how the eight dignitaries can mask themselves: As orangutans ! The ministers are enthusiastic about the prospect of creating great horror, especially among the women. They have jerseys that are covered with tar and tow is glued onto them. Then Hopp-Frosch ties them together in a circle with a chain, but adds two chains that intersect the circle at right angles. In the ballroom, the large chandelier has been removed from the dome, but not the chain on which it was hanging. When the king and his ministers appear in their disguise, to the great horror of the audience, Hopp-Frosch accidentally attaches the chain cross to the hook of the chandelier chain, which can be moved over the roof by a counterweight. Hopp-Frosch lets the eight masked men pull up, gets a torch, jumps up with them and lights the bundle of those hanging, who are quickly in bright flames and burn. Hop-frog escapes over the roof; neither he nor Tripetta are ever seen again.

The table of contents is based on the translation by Hans Wollschläger .

interpretation

Hervey Allen interpreted the story as an allegory: poetic ingenuity (Hopp-Frosch) and imagination (Tripetta) join forces against the prose of everyday life and money-making (the king and his ministers). Marie Bonaparte sees little Oedipus at work killing his (foster) father, in Tripetta she sees the sylphidic incarnation of Poe's mother who died early. The exotic origin of Hopp-Frosch and Tripetta also points to a structure in which the enslaved colonized strike back against their arrogant masters.

Emergence

The story is inspired by the Bal des Ardents reported by Jean Froissart . Of course, the masked people only catch fire there by accident. Poe wrote to Annie Richmond in February 1849: “The five pages of prose I finished yesterday are called - what do you think? - I'm sure you will never guess - 'Hop frog'! Imagine your Eddy writing a story with a title like this: 'Hop-frog'! I am sure you will never guess the terrible subject after the title. "Hopp-Frosch says goodbye to his audience with the words:" As for me, I'm just Hopp-Frosch, the joker - and this is my last fun. ”Eight months after Poe wrote this, he died. The story can therefore also be read as the poet's farewell and legacy, comparable to Shakespeare's romance The Tempest .

German translations (selection)

- 1861: unknown translator: jumping frog. Scheible, Stuttgart.

- around 1900: Johanna Möllenhoff : The black cat. Reclams Universal Library, Leipzig.

- 1901: Hedda Moeller and Hedwig Lachmann : Froschhüpfer. JCC Bruns, Minden.

- 1909: Bodo Wildberg : Poggehupp. Book publisher for the German House, Berlin.

- approx. 1920: Carl Wilhelm Neumann : Huppefrosch. Reclams Universal Library, Leipzig.

- 1922: M. Bretschneider : The frog hopper. Rösl & Cie. Publishing house, Munich.

- 1922: Gisela Etzel : Hopp-Frosch. Propylaea, Munich.

- 1923: Wilhelm Cremer : The Dwarf's Revenge. Verlag der Schiller-Buchhandlung, Berlin.

- ca.1925 : Bernhard Bernson : Hopp-Frosch. Josef Singer Verlag, Strasbourg.

- 1930: unknown translator: frog hopper. Fikentscher, Leipzig.

- 1945: Marlies Wettstein : Hoppefrosch. Artemis, Zurich.

- 1953: Günther Steinig : Hopping Frog. Dietrich'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig.

- 1966: Hans Wollschläger : Hopp-Frosch. Walter Verlag, Freiburg i. Br.

- 1989: Erika Engelmann : Froschhüpfer. Reclams Universal Library, Stuttgart.

- 1989: Heide Steiner : Hopp-Frosch. Insel-Verlag, Leipzig.

Web links

- Original English text

- German translation by Gutenberg

- Hop-frog at Zeno.org .

- "Huppefrosch", illustrated adaptation by Stefan Mart , in: Märchen der Völker , Hamburg 1932

Individual evidence

- ↑ See Hervey Allen: Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe. New York 1934 (reprint 2007), p. 513.See also Ronald Gottesman: 'Hop-Frog' and the American Nightmare, 'Masques, Mysteries and Mastodons. In: Benjamin F. Fisher: A Poe Miscellany. The Edgar Allan Poe Society, Inc., Baltimore 2006, pp. 133-144, here pp. 136 f., Online .

- ^ Marie Bonaparte: Edgar Poe. Volume III. Vienna 1934, pp. 40-46.

- ^ Marie Bonaparte: Edgar Poe. Volume III. Vienna 1934, p. 40.