The double murder on Rue Morgue

The Murders in the Rue Morgue (also: The Murders in the Rue Morgue ; english The Murders in the Rue Morgue [ ry: mɔrg ]) is a short story of the American writer Edgar Allan Poe , the first time in April 1841 the magazine Graham's Magazine published . It is the first of three short stories that revolve around the deductive analyzing detective C. Auguste Dupin .

content

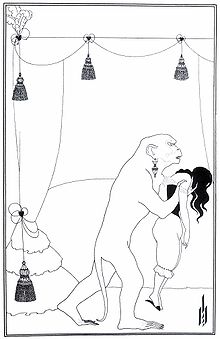

Together with his partner, C. Auguste Dupin investigates the inexplicable murders of two Parisian women. These were brutally murdered on the fourth floor of their otherwise empty house. But the case cannot be resolved at first. All the doors and windows to the room are locked from the inside , so it is a mystery to the police how the murderer (s) escaped from the scene. But Dupin is investigating the case himself and thanks to his brilliant analytical mind he can get to the bottom of the matter and determine who the murders are to be attributed to. The murderer of the Paris women is an orangutan who escaped from its owner, a sailor. The animal had always watched its owner shave. After it escaped from its cage, it fled into the house where the women lived and killed one of the residents while mimicking the shaving process with a razor . The other was brutally strangled by him and pushed upside down into the fireplace. The monkey then fled through a sliding window that was only apparently attached to the window frame with a nail (which had now broken through).

Interpretative approach

The actual narrative in the unabridged version is a Sir Thomas Browne motto about “amazing questions, the solution of which is not beyond the realm of possibility” ( “puzzling questions, are not beyond all conjecture” ) and a subsequent theoretical treatise on the ability to cognize of the human mind. In this treatise-like essay, the style of which is supposed to create the impression of scientificity, the possible perfecting of human intellectual abilities and their application in precise observation and logical-analytical combination is asserted. With the help of practical examples, the anonymous first-person narrator then tries to prove the correctness of the theoretical considerations. After this opening credits, the first-person narrator draws attention to the figure of the impoverished nobleman C. Auguste Dupin, who from his point of view perfectly embodies the previously discussed analytical abilities of the human mind, and illustrates its extraordinary intellectual power, its psychological empathy and its ability for mind reading with the description of a particular episode.

The story itself begins with the newspaper reports about a horrific murder case, without directly depicting the horror of the crime in contrast to the horror stories (“gothic tales”) . After a dramatic increase in the suspense of the plot, the case, which at first seems unsolvable, is resolved with an explanation of the inexplicable by the supreme detective Dupin; the human mind thus triumphs over the irrational.

Corresponding to Poe's own literary theoretical ideas about the short story, this narrative also proves to be constructed from the end; the tension and the single effect postulated by Poe can only be achieved if the individual construction elements of the story are specifically selected with a view to the end and artfully nested. The dating remains fuzzy; however, frequent references to Parisian daily newspapers, street names or French expressions suggest the appearance of reality. The crime documented in the various newspaper reports initially appears extremely mysterious and insoluble. The protagonist Dupin is interested in the puzzling case for ambivalent motives: On the one hand, clarifying it gives him intellectual pleasure ("amusement") and gives him the opportunity to demonstrate his special intellectual abilities . On the other hand, he shows a certain human sympathy because he wants to help his friend Le Bon, who is suspected of having committed the crime.

The underlying crime was committed in a locked room , which in Poe's narrative is a model for a core element of the mystery structure of the case. The narrator accompanies Dupin on the crime scene inspection; however, all observations that Dupin makes are initially concealed from the reader. At the end of the story, when the case is surprisingly cleared up, he learns that Dupin has discovered a way to open a window. As the reader can only see in the final part, Dupin resolved the case immediately during the initial inspection of the crime scene.

Before Dupin's lengthy monologue at the end of the narrative, in which he intellectually resolves the case, additional dramatic tension is built up as the detective and the narrator expect a mysterious visitor. The appearance of the seaman, whom Dupin found through his newspaper advertisement, not only creates an additional element of tension; At the same time, the report of the seaman, which the narrator summarizes, helps to confirm the detective's analytical reasoning. The deduction and exclusion of possibilities in the intellectual resolution of the case is primarily presented by Poe not as a mind game, but predominantly as a narrative that arranges the facts with regard to the ultimate solution. This structure of the plot with withholding the solution by the detective and the subsequent explanation is not only a prototype of the other Dupin stories of Poe, but is also a model for almost all classic detective stories. The truth of the story therefore ultimately only means factual accuracy, which is only consistent in the fictional narrative, but not in reality.

Poe consistently subordinates all events to the "single effect" ; Various “narrative tricks” are used to work towards the given solution in the sense of his theory of the “unity of effect” . Therefore, the reader has no real opportunity for intellectual guesswork. Poe's “single effect” , which is reached by the climax of the story in the Dénouement , lies in the suggestive persuasion of the reader that man can perfect his intellectual abilities and thereby become capable of solving seemingly unsolvable problems.

This suggestion is further reinforced by a correspondence between the narrative time and the narrated time in Dupin's monologue, while earlier in the first-person narrator's report, a time lapse alternates with a time lengthening in the dialogue. At the same time, Dupin's narrative perspective is adopted in the final part in order to bring his person and his skills to the fore in terms of narrative technology.

The design of the figure of the amateur detective Dupin clearly shows Poe's consideration for the tastes and latent interests of his contemporary reading public. Despite the propagation of Franklin's work ethic at the time, readers of American magazines had not yet completely lost their hidden admiration for the European aristocracy; However, Poe believed, who himself despised the masses and felt as an aristocrat, could only expect an impoverished nobleman from his audience, who has lost his feudal political power, but nevertheless still retains his aristocratic "nature" and his eccentric lifestyle. As a French nobleman, he continued to meet the American ideal of the French enlightenment spirit.

His first name Auguste (= the sublime) emphasizes his outstanding position as well as the detailed, exaggerated description of his social position (“excellent, illustrious”) ; Poe's character drawing makes him a heroic role model who, as in Emerson's The American Scholar or numerous popular stories about the pioneers of the West, can be considered an ideal worth striving for.

However, Dupin's personality does not experience any further development in the story; He is reduced by Poe as a type to his intellectual activity, which is emphasized all the more by his eccentricity ( "bizarre" ). There are also no further pictorial details in his description, as would be typical for later detective characters in the succession of Poe, such as Holmes' pipe and cap or Father Brown's umbrella.

The description of Dupin and the description of the events are from the perspective of the first-person narrator, who participates in the world of fictional reality as the experiencing self and reflects on it as the narrative self. As a character, the narrator remains anonymous and is hardly characterized in a tangible form, but assumes a multiple function in Poe's story. As a reporting eyewitness, on the one hand he ensures the verification of the thesis and narrative, on the other hand he anticipates the reactions of the readers within the story as a “dramatic audience” in order to suggest the admiration of Dupin to the reader. As a foil for Dupin, his own helplessness in the face of his train of thought or chain of thought lets the protagonist appear in an even more radiant light. In addition, he takes on the role of mediator between the reader and the detective and creates an opportunity for Dupin to demonstrate his thoughts in a narrative manner. Poe uses this particular narrative situation, which becomes the classic pattern of many subsequent detective stories, not only in his other Dupin stories, but also in The Gold Bug , where the first-person narrator appears equally as a friend and admirer of an extraordinary main character.

The Murders in the Rue Morgue also proves to be carefully and precisely constructed in the narrative details . The multi-layered, sometimes eclectic, narrative and style elements are consistently geared towards the unity of effect in accordance with Poe's own poetological demands . In addition to elements of the literary riddle, the history of the philosopher ( e.g. Voltaire's Zadig ), the gothic novel , the adventure novel and the philosophical essay, there are also moments of the edifying story and the sermon. With its artistry, the narrative not only suggests a belief in the capabilities of the human mind, but also addresses the reader's need for sensation and shudder, which is then suppressed again by the appearance of logical deduction. In this way, in the end, the fiction of an ideal world is produced for the reader; In this respect, Poe's narrative not only shaped the foundations of later detective literature , but also of escape literature .

History of origin

Poe changed the title in the manuscript from The Murders in the Rue Trianon Bas with a suggestive alliteration to The Murders in the Rue Morgue , thereby emphasizing the area of horror or morbidity. Unlike a pure sensational or horror story, the original version of the text consists of a motto taken from Sir Thomas Brownes Hydriotaphia or Urne Buriall (1658), a pseudo-scientific treatise on the capabilities of the analytical mind ( "analytical mind") ) and the actual narrative, which, according to the narrator, provides a comment or an explanation of the theses in the preceding treatise (“a commentary upon the propositions just advanced”) . The initial motto also illustrates the subject of the knowledge of the human mind; In Poe's time, Sir Thomas Browne, as a scientific scholar, doctor and homo religiosus , primarily represented bridging the conflict between belief and knowledge.

In structure, Poe's original overall story resembles an edification sermon on the perfection of the human mind and its application with the structural components text, explicatio , applicatio and coda. A similar adoption of sermon forms can be found not only in numerous essays of the 18th and 19th centuries, but also occupies a special position in Melville's Moby-Dick in Chapter IX, "The Sermon" . In later editions and reprints of The Murders in the Rue Morgue the motto and treatise are often left out at the beginning; thus, contrary to Poe's original intention, this element of the sermon form is omitted .

As a magazine writer and editor, Poe had already stated in a letter to Thoma W. White on April 30, 1835 that as a writer he had to take the bad taste of the reading public into consideration and therefore resort to exaggeration and flattening. Against this background, the main character Dupin is designed as a figure whose contradictions are resolved in the “single effect” presented above, the suggestion of his special analytical cognitive abilities. In order to stimulate metaphysical speculation and to pretend profundity for an educated reading public, Poe at the same time ascribes a "Bi-Part Soul" to him.

Impact history

Poe's short story, published in 1841, is considered the prototype of the genre of detective history emerging in the 19th century and one of the first stories to make use of the technology of " locked space ". Dupin occurs as the main character again in 1842 in The Mystery of Marie Rogêt ( The Mystery of Marie Rogêt ) and 1844 in The Purloined Letter ( The Purloined Letter on). The constellation of Dupin's assistant first-person narrator , who mediates between the brilliant detective and the reader, and the structure of the short story (demonstration of Dupin's detective skills, crime and unsuccessful police investigations, inspection of the crime scene, investigation and spectacular resolution) provide the successful Conception for almost every subsequent detective story, such as Arthur Conan Doyle , who 45 years later expanded this composition even further with his figure of Sherlock Holmes (very similar to Dupin) . Even as the type of "amateur detective" who looks down at the police with contempt, Dupin is the forerunner of many later detective figures.

However, Poe's story deviates from the later scheme of the classic detective story at various points: In the end, the alleged double murder turns out to be an act of an animal that has gone wild and thus an accident, but not a crime with a motive. In addition, instead of numerous suspects, there is only one suspect who is actually never really suspect. The (reading) tension in Poe's rather "accidental" detective story does not grow from guessing, but rather from "admiring comprehension" of Dupin's thought processes.

The work also had a more immediate effect on Israel Zangwill , whose The Big Bow Mistery is now also referred to as a classic of the crime genre. The motif of murder behind closed doors appeared for the first time in Poe, but Zangwill directly influenced Gaston Leroux with The Secret of the Yellow Room (1904).

Dupin's cult-like veneration of the night ("The sable divinity") and its bizarre properties point back to romanticism . His activity as an amateur detective, who personifies the belief in human reason and is far superior to the Paris police, expresses a rational belief in progress. The Murders in the Rue Morgue is after the previous short stories, which, such as Ligeia or The Fall of the House of Usher, were still largely in the gothic tradition of the horror story, the first significant story by Poe in which the thematization of the analytic minds (analytic mind ) is in the foreground. The story shows the poles between which Poe's work is located in the larger context of the 19th century: the conflict between rationality and irrationality, between the emergence of the natural sciences and the inevitable romantic feelings. At the end of the story, Dupin turns against the overemphasis on fantasy and thus on romanticism by describing the incompetent, rather ridiculous-looking Parisian police prefect with a quote from Rousseau .

German translations (selection)

The story was printed in numerous anthologies. The DNB lists around 90 editions of the original version and the German translation in alternating combinations with other stories. Some of the editions contain a foreword by Charles Baudelaire . Baudelaire was an avid reader and a translator of Poe into French.

- ca.1890 : Alfred Mürenberg : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Spemann, Stuttgart.

- 1896: unknown translator: The murders on Morgue Street. Hendel, Halle / S.

- around 1900: Johanna Möllenhoff : The murders in the Rue Morgue. Reclams Universal Library, Leipzig.

- 1901: Hedda Moeller and Hedwig Lachmann : The murder in Spitalgasse. JCC Bruns, Minden.

- 1909: Bodo Wildberg : The murders in the Rue Morgue. Book publisher for the German House, Berlin.

- 1922: Gisela Etzel : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Propylaea, Munich

- 1922: Hans Kauders : The murder in the Rue Morgue. Rösl & Cie., Munich.

- 1923: Wilhelm Cremer : The murder in de Rue Morgue. Verlag der Schiller-Buchhandlung, Berlin.

- ca.1925 : Bernhard Bernson : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Josef Singer Verlag, Strasbourg.

- 1925: unknown translator: The murder on Rue Morgue. Mieth, Berlin.

- 1927: Julius Emil Gaul : The murders on Rue Morgue. Rhein-Elbe-Verlag, Hamburg.

- 1930: Fanny Fitting : Murder on Rue Morgue. Fikentscher, Leipzig.

- 1948: Ruth Haemmerling and Konrad Haemmerling : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Schlösser Verlag, Braunschweig.

- 1953: Richard Mummendey : The murders on Rue Morgue. Hundt, Hattingen.

- 1953: Günther Steinig : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Dietrich'sche Verlagbuchhandlung, Leipzig.

- 1955: Arthur Seiffart : The double murder in the Rue Morgue. Tauchnitz Verlag, Stuttgart.

- 1966: Hans Wollschläger : The murders in the Rue Morgue. Walter Verlag, Freiburg i. Br.

- 1989: Siegfried Schmitz : The murders in the Rue Morgue. Reclams Universal Library, Stuttgart.

- 2017: Andreas Nohl : The double murder on Rue Morgue. dtv, Munich.

Adaptations

- In 1932 the material was filmed under the direction of Robert Florey with the title Murder in the Rue Morgue .

- As part of the British TV series Detective , the story was filmed as the 35th episode in 1968.

- In 1971, the loose film version Murder on Rue Morgue was released, directed by Gordon Hessler .

- In 1986 there was an American TV adaptation with George C. Scott in the role of Dupin. In other roles: Val Kilmer and Rebecca De Mornay .

- The British writer Clive Barker wrote the story New Murders in the Rue Morgue , which is based heavily on Poe's original.

Five radio plays were produced in Germany:

- 1946: The murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: BR . The director and speaker are no longer known.

- 1956: The double murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: WDR . Director: Raoul Wolfgang Schnell . Speaker: Ernst Ginsberg , Dietmar Schönherr , Arthur Mentz , Heinz Schimmelpfennig , Lilly Towska u. a.

- 1965: The murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: BR. Director: Edmund Steinberger . Speaker: Horst Tappert , Erik Jelde , Christian Marschall , Christian Wolff , Wolf Euba u. a.

- 1991: The double murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: Broadcasting of the GDR . Director: Jörg-Michael Koerbl . Speaker: Florian Martens , Sven-Erik Just , Klaus Piontek , Horst Lebinsky , Michael Kind u. a.

- 2007: The double murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: Maritim-Verlag. Director: Dennis Hoffmann . Speaker: Frank Glaubrecht , Volker Brandt , Gerd Baltus , Christian Rode u. a.

- 2013: The double murder on Rue Morgue . Producer: Die Mediabühne. Director: Annelie Krügel . Speaker: Till Hagen , Sascha Rotermund , Peter Kirchberger , Christian Rudolf .

- 2015: The Man in Orange (in the “Sherlock Holmes & Co.” series ). Producer: Romantruhe Audio. Speaker: Douglas Welbat , Manfred Lehmann , Uve Teschner , Helmut Krauss , Gabi Libbach , Merete Brettschneider , Martin Sabel u. a.

- The British heavy metal band Iron Maiden processed some of the stories in the song Murders in the Rue Morgue on their 1981 album Killers .

- 2013: The German rapper Casper wrote the song La Rue Morgue for his album Hinterland .

literature

- Paul Gerhard Buchloh : Edgar Allan Poe The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller et al. (Ed.): The American short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 94-102.

- Alexandra Tischel: Monkeys like us. What the literature says about our closest relatives. JB Metzler, Stuttgart 2018, ISBN 978-3-476-04598-0 , pp. 113–126.

Web links

- The double murder on Rue Morgue at Zeno.org ., German translation.

- German translation by Gutenberg

Individual evidence

- ↑ The following is quoted after the German text edition on Projekt Gutenberg-De and the edition of the English original text on Wikisource; see. Web links below.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh : Edgar Allan Poe · The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , p. 96f.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe · The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , p. 97.

- ↑ See in detail Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe · The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 97-99.

- ↑ See more detailed Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe · The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , p. 99f.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 101f.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 95 f.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , p. 100 f.

- ↑ See Sven Strasen and Peter Wenzel: The detective story in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story. Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-7720-3370-9 , pp. 84-105, here p. 92 f.

- ↑ Cf. Manfred Smuda: VARIATION AND INNOVATION: Models of literary possibilities of prose in the successor of Edgar Allan Poe. In: Poetica , Vol. 3 (1970), pp. 165–187, esp. P. 172. See also Sven Strasen and Peter Wenzel: The detective story in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story. Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-7720-3370-9 , pp. 84-105, especially pp. 85 and 92-95.

- ↑ See Sven Strasen and Peter Wenzel: The detective story in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story. Francke Verlag, Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-7720-3370-9 , pp. 84–105, here pp. 85 and 92–95.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Walter (Ed.): Reclams Krimi-Lexikon . Authors and works. Philipp Reclam Jun., Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-15-010509-9 , p. 452 f.

- ↑ See Paul Gerhard Buchloh: Edgar Allan Poe The Murders in the Rue Morgue. In: Karl Heinz Göller u. a. (Ed.): The American Short Story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02212-3 , pp. 100 and 94.