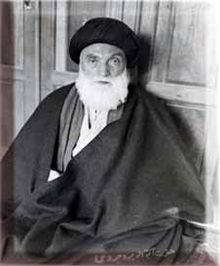

Hossein Borudscherdi

Hossein Ali Ahmadi Tabatabai Borudscherdi (also Husain Ali Ahmadi Tabatabai Borujerdi , Persian آیتالله العظمی حسین طباطبایی بروجردی; * 1875 in Borudscherd , Lorestan , Iran ; † March 30, 1961 in Qom ) was an Iranian Grand Ayatollah and the last Marja-e Taghlid recognized by all Shiite clergy .

Life

In 1875 Hossein Borudscherdi was born in Borudscherd, to which his Nisba refers. He studied Islamic jurisprudence ( Fiqh ), was a student of Achund Mohammad Kāzem Chorāsāni and developed a great influence through his own interpretations and jurisprudence. B. Morteza Motahhari but also many other clergy of his time. His hadith criticism on a scientific basis is considered outstanding . Starting from the investigation of small periods, he traces the chain of narration and questions the authenticity of many hadiths.

effect

The position of Marjah was vacant after the death of Grand Ayatollah Hossein Haeri Yazdi in 1941. Many religious scholars wanted Borudscherdi as their successor. In 1944, when Borudscherdi went to Tehran for medical treatment, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi visited Borudscherdi personally in the hospital, a rare gesture by the monarch. The visit was taken as the monarch's approval of his calling as mardschaʿ.

In 1949, after the assassination attempt on Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi , and after Borudscherdi had been recognized as the absolute authority (or also: the source of imitation) by all Shiite Grand Ayatollahs, he summoned more than 2,000 religious scholars to a congress in Qom to follow the quietistic tradition there to remind and renew the Shiite clergy. As long as Borudscherdi was alive, he publicly supported Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi several times. After the assassination attempt on the Shah in February 1949, he ended his speech in favor of the Shah with the words: "May God protect your kingdom".

Under his leadership, the students in the Qom seminars were urged not to be actively involved in politics. So he took Seyyed Modschtaba Mirlohi, better known under the name Navab Safavi and Seyyed Abdol-Hussein Vahedi, the founders of Fedajin-e Islam , from the seminary in Qom because of their involvement in assassinations ( assassination attempt on Ahmad Kasravi , assassination attempt on Abdolhossein Hazhir , Assassination attempt on Ali Razmara ) forcibly de-registered. Borudscherdi also put pressure on Khomeini , who was an insignificant cleric at the time, because he believed him to be the spiritual mentor of fedayeen-e Islam. For the same reason, the relationship between Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi and Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani was clouded. Despite the strained personal relationships, Borujerdi campaigned for Kashani's exile to be lifted in 1950, his return to Iran and his release in 1956 after the fall of Mossadegh.

Borudscherdi saw the monarchy as the antithesis to the secular republic and communist atheism. After initially supporting Prime Minister Mossadegh on the question of the nationalization of the oil industry and its political consequences , he increasingly moved away from Mossadegh over time. He even threatened to emigrate to Najaf, which would have meant the political end of his government. Borudscherdi, who worked closely with parliamentary president Ayatollah Kashani during this time, even supported the replacement of Mossadegh in the end. On June 13, 1953, on the festival of the breaking of the fast , Kashani brought more protesters against Mossadegh to the streets than Mossadegh's supporters in a counter-demonstration a week later. Borudscherdi is therefore, according to recent research results, as a decisive factor in the overthrow of Mossadegh on August 19, 1953, since it was the clergy who organized the massive pro-Shah demonstrations on that day that ultimately Mossadegh to give up his office in favor of Fazlollah Zahedi forced.

It is therefore not surprising that Borujerdi was not against the persecution and the ban of the Tudeh party and the burgeoning persecution of the Baha'i , both in the years 1954–1955. In a fatwa (1955) he declared Pepsi-Cola to be reprehensible because the Iranian concessionaire was an avowed Baha'i.

However, his quietist attitude did not prevent Boroudscherdi from exerting his influence on important political issues. Opposed to women's emancipation and land reform, he issued a fatwa on May 16, 1960 against the reforms of the Shah. Out of consideration for Boroudscherdi, the Shah only implemented his reform program after his death and after a number of concessions to the clergy, which would go down in Iran's history as the White Revolution . Islam classes in schools were expanded, entertainment events were banned in public places and in public institutions during religious holidays , the Shah's obligation to advocate Shiite Islam was renewed, state support for the construction of mosques increased and the number of pilgrims , who were able to travel to Mecca with government support increased.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini polemicized later against Borudscherdi in 1970 in his treatise Hokumat-e eslami (The Islamic State) and described him and others as pseudo-pious :

“Because they are an obstacle to our reforms and our movement. They tied our hands. In the name of Islam, they harm Islam. "

Quote

Hossein Borudscherdi is ascribed the following quote on the occasion of the fall of Mohammad Mossadegh in 1953:

“We, the clergy, should found an Islamic state? ... We would be a hundred times bigger criminals than those who are now in power. "

See also

literature

- Heinz Halm : The Schia . Darmstadt 1988, ISBN 3-534-03136-9 .

Web links

- Hossein Borudscherdi . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica (English, including references)

- Biography (English)

swell

- ↑ Heinz Halm: The Schia. Darmstadt 1988 page 155

- ↑ Darioush Bayandor: Iran and the CIA. New York, 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ Shahrough Akhavi: Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran. State University of New York Press, 1980, p66.

- ↑ Heinz Halm: The Schia. Darmstadt 1988. page 153

- ↑ Houchang Chehabi: Clergy and State in the Islamic Republic of Iran. 1993. page 19

- ↑ Darioush Bayandor: Iran and the CIA. New York, 2010, p. 78.

- ↑ Darioush Bayandor: Iran and the CIA. New York, 2010, pp. 79f.

- ↑ Darioush Bayandor: Iran and the CIA. New York, 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ Darioush Bayandor: Iran and the CIA. New York, 2010, pp. 147-154.

- ^ Karl-Heinrich Göbel: Modern Shiite Politics and State Idea. 1984. page 171

- ↑ Shahrough Akhavi: Religion and Politics in Contemporary Iran. State University of New York Press, 1980, p. 92.

- ↑ Bahman Nirumand et al. Keywan Daddjou: With God for power. A political biography of the Ayatollah Khomeini. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1989, page 88

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Borudscherdi, Hossein |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Borujerdi, Husain |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Shiite clergyman, last Mardschaʿ-e Taghlid |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Borudscherd , Lorestan , Iran |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 30, 1961 |

| Place of death | Qom |