II-VI

The II-VI - cadence is the most common chord compound in the jazz music . The tonic can be a major or minor chord. The bass note is typical for jazz in the fifth case . The cadence often occurs without a dissolving tonic. It can be derived from the classic full cadence with the added sixth on the subdominant .

An alternative functionally harmonious interpretation takes the II chord as a dominant lead .

Use in the major scale

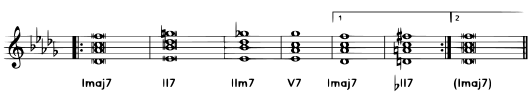

The cadence of the seventh chords with chord symbols is in major:

IIm 7 - V 7 - I maj7

Used Moll - seventh chord of the second stage, the major -Septakkord the fifth and the major chord at the first stage major seventh or sixth large.

If C is the tonal center , you get the chord progression (in jazz, changes are the harmonic changes of a piece that form the basis for improvisation):

Dm 7 - G 7 - C maj7 ( )

Use in the minor scale

The II-VI chord progression is applicable not only to the major, but also to the (harmonic) minor scale. In this minor scale, the cadence is:

IIm 7 ♭ 5 - Vm 7 ♭ 9 / ♭ 13 - In maj7 or IIm 7 ♭ 5 - Vm 7 ♭ 9 / ♭ 13 - In 6

All three chords use different minor scales: IIm 7 ♭ 5 natural minor, V 7 ♭ 9 harmonic minor, Im melodic minor. The minor tonic either consistently contains the major seventh or the major sixth; but very often also the minor seventh from the natural minor scale.

Wolf Burbat sums up the whole sound material: 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, 6, b7, maj7. From this he builds various scales. Jungbluth uses the melodic minor upwards scale . In jazz there is an audible confrontation with the tones of this scale. Melodic minor is useful for creating melodies, harmonic minor is only used by the V 7 ♭ 9 / ♭ 13 , namely vertically.

Or as an altered variant:

IIm 7 ♭ 5 - V 7alt - Im maj7 or IIm 7 ♭ 5 - V 7alt - Im 6

The first chord of this sequence is a semi-diminished chord on the second degree and the second chord is harmonically seen as a dominant seventh chord in harmonic minor, which leads to the lowering of the ninth and the third, or alternatively usually an altered dominant seventh chord , which also includes the excessive ninth (# 9 ) may contain. For example, if you have A minor as your basic key, the chord progression is:

Hm 7 ♭ 5 - E 7 ♭ 9 / ♭ 13 - Am maj7 or Hm 7 ♭ 5 - E 7 ♭ 9 / ♭ 13 - On 6

b9 is the f, b13 is the c, the g is missing, or

Hm 7 ♭ 5 - E 7alt - Am maj7 or Hm 7 ♭ 5 - E 7alt - Am 6 Here you have the fisis as # 9, which corresponds enharmonically to the g ( i.e. the blue note ).

Relation to the fifth case sequence

The root notes of this chord progression form a fifth case sequence :

... H - E - A - D - G - C - F - ...

Conversely, the pure fifth fall sequence almost exclusively represents a II-VI sequence, such as the beginning of Autumn Leaves :

Dm 7 - G 7 - C maj7 - F maj7 - Hm 7 ♭ 5 - E 7 - Am (repetition) This corresponds to: II - V - I - VI - ii - v - i

Practical use

Typical final cadence

The II-VI connection is often found at the end of a song or chorus.

Examples:

- and I (Dm 7 ) think to myself: (G 7 ) WHAT A WONDERFUL (C) WORLD

- Tell me (Em 7 ) dear ARE YOU (A 7 ) LONESOME TO- (D) NIGHT

- (Dm 7 ) SUMMER FEELING (G 7 ) with Bacardi (C) Rum

- (Am 7 ) saying SOMETHING (D 7 ) STUPID like I (G) love you

- DON'T (Am 7 ) WORRY, (D 7 ) BE (G) HAPPY

- It's (Em 7 ) just another (A 7 ) MANIC (D) MONDAY

- (On the 7th ) I want to- (D 7 ) back to WESTER- (G) LAND

Jazz improvisation

A repertoire of solo phrases and chord voicings via the II-VI connection are part of the tools of every jazz musician

- the harmonious connection occurs in almost every standard and

- Solo phrases mastered in one key above II-VI also sound good in another key.

Some jazz standards consist almost exclusively of such connections, as the changes (M 7 denotes the major seventh there) of "Tune-up" ( Miles Davis ) show:

for listening (with a repetition).

The harmonies snap into the third measure of each phrase in a target sound to which the previous levels refer. The target sounds are relatively far apart: D major has 2 sharps, C major no accidentals and B major again 2 Bes (see: Circle of Fifths ). Cohesion creates here, however, that the target sounds at the beginning of the next phrase are "missed" and can thus be used as the second level of the next target sound. The only sound that breaks out of this scheme is the E flat major sound labeled IV. (IV in relation to the still valid B flat major). This sound is necessary to find your way back to the starting point within the 16 bars. If you were to spin the model further, you would arrive at A flat major. At this point, E flat major offers itself as a bridge between B flat major and E minor, since E flat major, as already mentioned, is the fourth degree of B, but on the other hand only through chromatic change of chord tones (E flat to E; B to B ) can be converted to E minor. The final, faster turn in the last bar leads back to the first chord of the piece as a conventional turnaround .

II-V

A split II-V is also often used: For example, the first six bars of Satin Doll ( Duke Ellington ) only use this phrase. In addition, the seventh bar comes up with a little surprise in that the immediately preceding II-V structure is not brought to an end as expected. Only the turnaround in the eighth bar is a complete II-VI connection to the repetition.

Often one finds scale material in textbooks as a basis for melodic soloing over II-VI (cf. scales for improvisation over the dominant seventh chord ). In our example, it can be enough to start improvisation that all of the sound material can be taken from the C major scale ( ionic mode ) without any problems . You can also get along well with the C major pentatonic scale. The alterations that give a melody line the right flavor come from either the blue notes of the basic key, tritone substitutions or parallel shifts of the specified chords.

VI-II-VI

The detailed sequence VI-II-VI, also in variants, is also common. If you start the sequence with I you have: I-VI-II-VI, where I-VI are tonic and minor parallels. In addition, VI and II are counter-sound and minor parallels of the subdominant, which functionally approaches the full cadence. In the rock / pop area you can also hear the variant in which II is replaced by IV: I-VI-IV-VI.

II-V-II-V

Chords spaced apart from fifths are also strung together as chains of II-V in different tonalities: For example Em - A 7 - Dm - G 7 (- C). The first sequence Em - A 7 is in D major, but dissolves into D minor ( free passage ), which means that the second II-V sequence in C major is reached at the same time.

VI-II-VI variants

On the one hand, you can replace the V chord with a suitable variant (Mixolydian, Altered, V 7 ♭ 9 with b9, # 11, 13) and there are the following options for the VIm 7 :

- # I ° 7 , uses the whole tone halftone scale

- bIII ° 7 , uses the whole tone half-tone scale

- II 7 , uses the above scale V 7 ♭ 9 with b9, # 11, 13, i.e. Mixolydian with a small ninth and an excessive fourth.

- VI 7 , uses the harmonic minor scale from the fifth level ( HM5 ) or the altered one .

- bIII 7 also uses the scale V 7 ♭ 9 with b9, # 11, 13, i.e. Mixolydian with a minor ninth and an excessive fourth.

The last variant, if it is started with the sixth chord of the tonic and given the altered dominant, gives a chromatic bass fall from the third to the root of the tonic.

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Mark Levine : The Jazz Piano Book. Advance Music, Rottenburg / N. 1992, ISBN 3-89221-040-3 , p. 23.

- ↑ Axel Jungbluth : Jazz harmony theory. Functional harmony and modality. Schott, Mainz a. a. 1981, ISBN 3-7957-2412-0 .