Intracerebral haemorrhage

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| I61 | Intracerebral haemorrhage |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

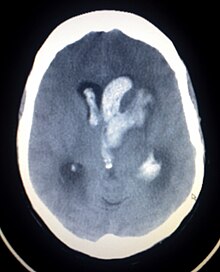

An intracerebral hemorrhage ( ICB , from the Latin intra- 'in' and cerebrum ' brain ' ) is a cerebral hemorrhage in the brain tissue itself. Intracerebral hemorrhages usually occur suddenly. Cerebral haemorrhage is hemorrhagic damage that causes the same symptoms as a stroke (ischemic damage). However, despite the same symptoms, these are two different diagnoses.

The most common causes are changes in small blood vessels that occur as a result of high blood pressure ( arteriolosclerosis ). Other causes can be changes in the vessels such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy or vascular malformations , but also traumatic damage - especially in connection with the use of anticoagulant drugs - play an important role. Rarely, inflammatory diseases of the brain or tumors can manifest as ICB. Even if bleeding from ruptured vessel wall sacs, the cerebral aneurysms , is usually subarachnoid bleeding, intracerebral bleeding can also be caused by aneurysm ruptures. In addition to the localization, the size of the bleeding is important for the prognosis and possible therapeutic measures. For example, 50 cm³ in supra tentorial bleeding and 20 cm³ in infratentorial bleeding are regarded as the critical limit for the further clinical course. Another unfavorable prognostic sign is the onset of bleeding into the ventricular system , which can lead to circulatory disorders of the cerebrospinal fluid .

The most frequent immediate trigger of an intracerebral hemorrhage is a rhexis hemorrhage of the central anterolateral arteries in its course through the area of the basal ganglia .

frequency

Every year around one million people worldwide and around 90,000 people in the European Union are affected by intracerebral haemorrhage. According to the Federal Statistical Office, a total of 33,996 people suffered intracerebral hemorrhage in Germany in 2008. 10 to 17% of all strokes are intracerebral bleeding. However, the proportion varies greatly from region to region. In China, a proportion of intracerebral bleeding in strokes of up to 39.4% has been determined.

Risk factors

The most commonly detected risk factor for intracerebral bleeding is arterial high blood pressure . This risk factor has been demonstrated in epidemiological studies in 70 to 80% of those affected. Treatment for arterial hypertension lowers the risk of developing intracerebral bleeding.

Another important risk factor is therapy with anticoagulant drugs . Therapy with oral anticoagulants such as phenprocoumon , which is used, for example, to prevent ischemic strokes in the presence of atrial fibrillation and to prevent deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism , leads to an 8-11-fold increased risk. Therapy with so-called platelet aggregation inhibitors such as acetylsalicylic acid - preventive use also after ischemic strokes and heart attacks - increases the risk of suffering from intracerebral bleeding. The combination of the two platelet aggregation inhibitors acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel , which is mainly used after heart attacks, leads to a significantly increased risk compared to treatment with acetylsalicylic acid alone. Therapy with platelet aggregation inhibitors also leads to a more rapid increase in the size of intracerebral bleeding within the first 48 hours. Treatment with heparins and fibrinolytics also increases the risk.

A low cholesterol level apparently leads to an increased risk of intracerebral bleeding, while a higher cholesterol level leads to less intracerebral bleeding. It is controversial whether cholesterol-lowering therapies with statins also lead to an increased risk of bleeding. Studies conducted on this question produced conflicting results.

Several studies also identified smoking (2.5 times the risk) and increased alcohol consumption as risk factors. Taking cocaine and amphetamines also increases the risk of bleeding. A comparatively increased bleeding volume was found in patients who were overweight or who had a raised body mass index .

Even ethnic affiliations have an impact on the risk of bleeding. Asians and Africans have a 1.5 to 2-fold increased risk. Another risk factor that cannot be influenced is age. The risk of bleeding increases with age.

treatment

ICB treatment is usually carried out in a neurosurgical or neurological intensive care unit and, if necessary, in the operating room.

Non-surgical treatment

Lowering blood pressure

In the treatment of arterial high blood pressure, a distinction must be made between primary prophylaxis (prevention of first-time intracerebral bleeding), acute treatment to reduce the risk of rebleeding, and secondary prophylaxis (prevention of re-intracerebral bleeding). The extent to which lowering blood pressure in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage is beneficial is controversial and has not been clearly established. The risk of rebleeding is likely to be reduced by lowering the blood pressure, but this could also lead to a reduced blood flow in the regions surrounding the intracerebral hemorrhage. Most of the studies that are available on this question, however, speak in favor of a rather beneficial effect of antihypertensive therapy. The current guidelines of the German Society for Neurology recommend lowering blood pressure. With known or pre-existing arterial hypertension, the blood pressure should be reduced to below 170 mmHg systolic and 100 mmHg diastolic (170/100 mmHg) or to a mean arterial pressure of below 125 mmHg if the values are above 180/100 mmHg. In the case of previously unknown high blood pressure, a reduction in values above 160/95 mmHg to below 150/90 mmHg or to a mean arterial pressure of below 100 mmHg is recommended. However, mean arterial pressure should not be reduced by more than 20 percent of the initial value.

Body temperature lowering

An increased body temperature has an unfavorable influence on the course of the disease, so lowering it to normal values is recommended.

Operative treatment

Whether neurosurgical treatment of intracerebral bleeding is promising depends on the location, cause of bleeding and clinical course. There are no clear guidelines as to when a patient with intracranial hemorrhage should receive surgical treatment. According to the guidelines of the German Society for Neurology , however, the following recommendations arise among others:

- In supra tentorieller localization in the area of the brain surgical treatment is not generally recommended; however, a craniotomy with hematoma removal may be considered if there is a deterioration in consciousness and if the bleeding is superficial.

- In the case of infra tentorial localization in the area of the cerebellum, relief surgery should be performed immediately if the clinical deterioration has ruled out other causes.

- According to Manio von Maravic, the following neurosurgical therapy options are available for cerebral mass hemorrhage:

- In the event of aneurysm or angioma, switch off the source of bleeding

- In the case of intraventricular bleeding and infratentorial bleeding with obstruction of the CSF drainage, ventricular drainage

- In the case of superficial lobar bleeding without ventricular invasion and a value of over 9 in the Glasgow Coma Scale with clinical worsening hematoma evacuation

- In the case of intracerebral haemorrhage with a diameter of more than 3 cm or a volume of more than 20 cm³, if there is severe clinical expression or a secondary symptom progression, hematoma evacuation.

Epileptic seizures

The risk of developing epileptic seizures after intracerebral hemorrhage is higher than after ischemic cerebral infarction. The risk is highest within 24 hours of the bleeding event. In a study related to this question, 4.2 percent of patients with supratentorial bleeding had an epileptic fit within the first 24 hours. In addition, the risk of seizures is higher if the bleeding is lobar than if it is subcortical. Typical epilepsy potentials in electroencephalography (EEG), which do not always lead to clinically detectable epileptic seizures, are detectable in almost a third of all patients with intracerebral bleeding.

Electroenzophalography is recommended for all intracerebral bleeding due to the frequency. If there is evidence of potential for epilepsy, prophylactic therapy with anticonvulsants is recommended. In the case of lobar intracerebral haemorrhages, prophylactic therapy can be considered.

If epileptic seizures occur in the context of intracerebral bleeding, the start of antiepileptic therapy is always indicated. A status epilepticus that has occurred, i.e. a generalized epileptic seizure that lasts longer than 5 minutes, or a focal epileptic seizure that lasts longer than 30 minutes, must be interrupted as quickly as possible. In the context of epileptic seizures and especially status epilepticus, complications, especially secondary bleeding and an increase in the midline displacement, can occur. Benzodiazepines are the first choice therapy . If ineffective, phenytoin , valproic acid and phenobarbital are used. If the status epilepticus is not interrupted with these drugs, the patients are intubated and treated with thiopental , midazolam and propofol .

literature

- Intracerebral bleeding . In: Guidelines for Diagnostics and Therapy in Neurology. Published by the “Guidelines” commission of the German Society for Neurology , Thieme Verlag , 5th edition, 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-132415-3 , pp. 380–397.

Individual evidence

- ^ "Intracerebral haemorrhage" AWMF guideline 030-002 - guidelines for diagnosis and therapy in neurology; Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart 2005, 3rd revised edition, ISBN 3-13-132413-9 .

- ↑ CL Sudlow, CP Warlow: Comparable studies of the incidence of stroke and its pathological types: results from an international collaboration. International Stroke Incidence Collaboration. In: Stroke Volume 28, Number 3, March 1997, pp. 491-499, ISSN 0039-2499 . PMID 9056601 .

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: Health diagnostic data of patients in hospitals (including deaths and hourly cases) 2008 . Technical series 12 series 6.2.1, Wiesbaden 2009. PDF version

- ↑ a b c d e f g Intracerebral bleeding . In: HC Diener, N. Putzki: "Guidelines for Diagnostics and Therapy in Neurology", Georg Thieme Verlag, 4th revised. Edition 2008. ISBN 978-3-13-132414-6 . PDF version

- ↑ LF Zhang, J. Yang a. a .: Proportion of different subtypes of stroke in China. In: Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation Volume 34, Number 9, September 2003, pp. 2091-2096 , ISSN 1524-4628 . doi : 10.1161 / 01.STR.0000087149.42294.8C . PMID 12907817 .

- ↑ a b c d e f T. Steiner: Intracerebral bleeding . In: Dirk Hermann, Thorsten Steiner, Hans C. Diener: Vascular Neurology: Cerebral ischemias, hemorrhages, vascular malformations, vasculitis and vascular dementia . Thieme-Verlag, 1st edition, June 2010, pp. 212–228. ISBN 978-3-13-146111-7

- ↑ S. Schwarz, K. Häfner u. a .: Incidence and prognostic significance of fever following intracerebral hemorrhage. In: Neurology Volume 54, Number 2, January 2000, pp. 354-361, ISSN 0028-3878 . PMID 10668696 .

- ^ R. Leira, A. Dávalos et al. a .: Early neurologic deterioration in intracerebral hemorrhage: predictors and associated factors. In: Neurology Volume 63, Number 3, August 2004, pp. 461-467, ISSN 1526-632X . PMID 15304576 .

- ↑ Manio of Maravic: Neurological emergencies. In: Jörg Braun, Roland Preuss (Ed.): Clinic Guide Intensive Care Medicine. 9th edition. Elsevier, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-437-23763-8 , pp. 311–356, here: pp. 316–318 ( cerebral mass hemorrhage ).

- ↑ S. Passero, R. Rocchi et al. a .: Seizures after spontaneous supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. In: Epilepsia Volume 43, Number 10, October 2002, pp. 1175-1180, ISSN 0013-9580 . PMID 12366733

- ^ PM Vespa, K. O'Phelan et al. a .: Acute seizures after intracerebral hemorrhage: a factor in progressive midline shift and outcome. In: Neurology Volume 60, Number 9, May 2003, pp. 1441-1446, ISSN 1526-632X . PMID 12743228 .

Web links

- S1 guidelines for intracerebral hemorrhage of the German Society for Neurology. In: AWMF online (as of 2008)