Jewish community Werl

The Jewish community in Werl in the Soest district ( North Rhine-Westphalia ) has been developing since 1565.

history

Jewish citizens have been documented since February 18, 1565. The Jew Jost or Joist paid twelve thalers escort money for two years . In 1566 and 1567, the Jews Nathan and Joist paid burial fees. The Jewish cemetery has been on Melsterstrasse since 1742 .

The number of Jews living in Werl was low for a long time. If individual names are passed down, for example Joist, Nathan and Jacob von Korbach, or in 1572 a “Cumpan Judde”, they are probably heads of household. The names of the women and children are not mentioned. In 1643 the treasury lists showed five Jewish heads of household. In 1690 the citizens of Werl complained to Landdrosten that the seven Jewish families comprised more than 40 people. The number of families that were allowed to settle in Werl was limited, so their number remained almost constant for decades. In a survey by the Hesse-Darmstadt government in 1804, there were still seven Jewish families. The synagogue director Levi Lazarus Hellwitz declared in 1817 that the Israelite community comprised 70 people. By 1840 the number of Jewish households doubled to 14 and then rose to 26 by 1895.

As almost everywhere in the Holy Roman Empire , the Jews in Werl were subject to multiple restrictions. In order to achieve the status of a so-called protective Jew , the head of the family had to acquire a letter of safe conduct from the sovereign. Such a letter of protection was indispensable almost everywhere for a settlement and often also for the practice of a profession. The city of Werl wanted to earn money from the lucrative business of issuing letters of passage and collect a city residence allowance. But in 1597, as Duke of Westphalia , the Cologne Elector Ernst von Bayern insisted on his right to issue the letters of safe conduct for the Jews of Werl. However, he did allow the city to collect a residence allowance. The residence of the individual Jews was secured by their property. It could happen that poor Jews were supported by their fellow believers, but it was also possible that they were expelled from the city so that better-off Jews could settle in their place. Because of the prohibition of Christians and Jews living together, Jews were exempt from billeting in times of war. They had to pay the city a special contribution to balance the burden . However, they were also obliged to guard duty and thus had the same duties as normal citizens, but only limited rights.

The number of Jews living in Werl remained roughly the same from 1849 to 1872 and rose only slightly in the following years. At the end of the 19th century, 135 Jews lived in the city, the number decreased to 91 by 1905 and to 38 by 1939, which corresponds to 0.38% of the population.

activities

The Jews traditionally ran money and pawn shops . Most of the time in Werl they were allowed to trade in animals and their meat as well as trade in general. In exceptional cases they were even allowed to practice a craft, despite the restrictions contained in the letters of safe conduct and against the resistance of the guilds . In 1656 the Jew Abraham was allowed to work as a glazier for a year; The distilling of aniseed wine or the production of malt were also permitted, apparently with the intention of generating higher tax revenues.

In the 19th century, the Jews in Werl mostly earned their living as merchants, cattle and horse traders and butchers. Between 1850 and 1864 nine Jewish apprentice butchers became masters. The cattle dealers lived on the outskirts of the city, the merchants mostly went about their business in the center. In the middle of the 19th century a bookseller and a goldsmith also settled down. The goods offered by the Jewish shops, such as tailor-made clothing, white goods , carpets, porcelain and glass, were also in great demand beyond the city limits.

Relationship between Jews and Christians

The council court was responsible for mediating insults, fights between Christians and Jews and warnings of debts. According to tradition, both parties were treated equally. Coexistence in the small town turned out to be pretty easy, provided the rules were followed. The Jewish emancipation took place in the Prussian era (from 1815) only gradually, as in the former duchy of Westphalia (had one of the Werl), the 1812 adopted concerning the conditions of bourgeois society of the Jews edict in the Prussian State did not apply. Many Jewish families in Werl belonged to the wealthy class and were called upon to perform all duties, but only gained unrestricted citizenship through the law of 1869 on the equal rights of denominations in civil and civic relationships .

Chewra Kaddisha

In 1817 the Chewra Kadischa was founded. This association was mainly devoted to the poor and the sick and the death support. It lasted until 1931.

tumult

The Jews demanded greater participation in the city's social life. The former synagogue head Levi Lazar Hellwitz had applied for admission to the Werler Schützenverein in 1826 . This triggered fierce resistance from the Christian citizenship and the association's board, so that at the shooting festival in 1826 there were tumultuous protests.

Poor foundation

The Jew Bendix Levi lived on Bäckerstraße in Werl from 1755. His widow Freidel Ruben wrote her will in 1799. A poor foundation was to be established from their total assets after deducting a few bequests. The city magistrate was in charge of the foundation . The widow died in 1808 and the foundation was established with a share capital of 6,500 Reichstalers. The poor in the city should be supported regardless of religion. The inflation after the First World War wiped out the capital and the foundation no longer existed.

synagogue

A first prayer room is documented in 1651. The Jew Isaak was rabbi of the Werler Jews, he wanted to rent a house to be able to use it as a prayer room. However, the house was awarded to the Capuchins, with reference to the Electoral Cologne Jewish Ordinance. The house was right next to the monastery church and according to the ordinance, Jews were not allowed to worship in the immediate vicinity of Christians. They had to keep at least four houses apart. According to records from 1679, 1692, 1693, 1716 and 1740, a prayer room was set up in the Rinsche house on Steinerstrasse. A plaque in German and Hebrew is still attached to the entrance today (2012). Detmar Josef von Mellin, the owner of the Rykenberg house at the time , mentioned in a letter the entrance to his house where the Jew house is now . There is evidence of its own synagogue on Bäckerstrasse in 1811. This was rebuilt in 1897, the classroom was outsourced and the gallery on which the women had sat was removed. The synagogue thus had enough space for the 144 members of the community at that time. The harmonium was renovated and cleaned in 1937 by the Stockmann company . In the same year, the Pieper construction business supplied sand, cement and bricks for repair work.

destruction

Before the arson attack on Reichspogromnacht , the head of the police station and the Werler fire brigade were informed of the impending attack by the deputy district administrator in Soest. The following call from November 10th has been reported: The synagogue in Werl is about to burn, so they have nothing to do with it. Stay away from this government action . Eyewitnesses have said that the synagogue burned around 8 a.m. and that it was infected with wood shavings. The neighboring houses were protected by the fire brigade that arrived later. The walls of the synagogue were torn down with a tear hook. Some important cult objects were not in the building at the time of the fire; they were later given to the Jewish community in Dortmund. The rubble from the burned down building was used as filling material, and some fragments were excavated during construction work in 1987. A stone with a memorial plaque stands on the site of the former synagogue.

Jewish school

Teaching the Hebrew language as a basis for reading the Torah and Talmud has always been of great importance. In order to convey the material, there were also classrooms in small communities. A Jewish school was first mentioned in a document in 1723. In the council minutes of 1742, a schoolmaster was named Nathan. The school, like the prayer room, was located in the Rinsche house on Steinerstrasse. From 1811 the school was located in the rooms of the synagogue on Bäckerstraße. A school house of their own was built in 1892 on Bäckerstrasse next to the synagogue. Because of the bad pay, the teachers changed frequently. In contrast to neighboring communities, the synagogue community did not receive any municipal grants. The school was probably closed in the spring of 1925, after which the pupils started school in the Catholic elementary school. The Jewish religious instruction was given once a week by a teacher from Soest.

time of the nationalsocialism

Riots in the time before

Not only in the Third Reich there were riots against Jews in the city. The Jewish cemetery was devastated in 1874 and 1894, and several tombstones were destroyed. The Jewish citizens offered a reward for apprehending the perpetrators, but to no avail.

After coming to power

Just a few days after the nationwide call to boycott Jewish goods , violent riots broke out in Werl. In a night action, the windows were broken in almost all Jewish shops. The events were reported in a report by Soester Anzeiger , but no criticism was made. Later SA men posted themselves in front of the shops on Steinerstrasse with signs that said Kauft was not to be read by Jews . Citizens who did not obey this call have their personal details recorded. A man, accompanied by two donkeys, marched through the city center, on the back of the donkey were posters with the words Werler buy nothing from Jews . Several Jewish shops closed later. In the period that followed, the Jewish citizens were excluded from the Werler associations. After the pogrom in 1938 , there were arrests and deportations to concentration camps ; Jewish students had to leave German schools. There were four Jewish school-age children between the ages of seven and fourteen. With the law on tenancy agreements with Jews passed in 1939 , the city was able to exert direct influence on living conditions. The families were brought together in so-called Jewish houses . Some properties were expropriated. On 27 April and 29 July 1942 a number of Werl were Jews into the ghetto Zamość and Theresienstadt concentration camp deported . None of these deported people survived.

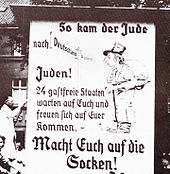

Pillar of shame

In the summer of 1938 a so-called Schandsäúle was set up on the Werler market square. It contained the names and addresses of all Jewish families and businesses. This measure was not ordered by a higher authority, Werler citizens exerted such massive pressure on the Jews. The four sides of the column of shame were labeled as follows:

- The Jewish families were mentioned with addresses; The list was supplemented with the appeal The real German avoids it.

- The Jewish shops in the city were enumerated and denounced.

- The caricature of a hook-nosed man with a backpack on his back was supplemented by the following cynical request: Jews! 24 hospitable states are waiting for you and look forward to seeing you. Get on your socks.

- What is not race in this world is chaff! Adolf Hitler

literature

- Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971.

- Amalie Rohrer , Hans Jürgen Zacher (ed.) Werl - History of a Westphalian city. 2 volumes. Bonifatius Verlag, Paderborn 1994, ISBN 3-87088-844-X .

- Helmuth Euler: Werl under the swastika. Brown everyday life in pictures, texts, documents. Contemporary history 1933–1945. Werl 1983.

Web links

- Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People (accessed on August 18, 2012)

Footnotes

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 9.

- ↑ Michael Jolk, Michael Ehlert: Commemoration of the Jewish Victims of National Socialism . In: Stadt Werl (ed.): 80 Years of the Pogrom Night 1938–2018. Memory of the Jewish victims of National Socialism. List of Werl's Jewish families in the 19th and 20th centuries ( Werler Memorial Culture series , ISSN 1615-0465 , issue 10). Werl 2018, pp. 5–20, here p. 6.

- ^ A b Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 8.

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 43.

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 47.

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 23.

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 15.

- ^ Rudolf Preising: On the history of the Jews in Werl . Coelde, Werl 1971, p. 28.