Clear altar

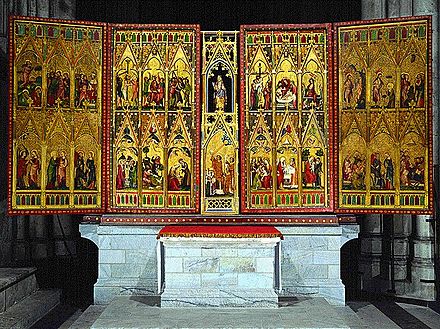

The plain altar or Clare altar is a six-meter wide Gothic winged altar, which was created in 1350 in Cologne. It originally stood in St. Clara, the church of the Poor Clare Monastery , and has been in Cologne Cathedral since 1809 . Today it is considered the "altar of superlatives."

history

The clear altar was donated for the church of St. Clara of the Poor Clare Monastery, consecrated in 1347. Isabella and Philippa, the daughters of Count Rainald I von Geldern, are considered to be the founders . The monastery itself was founded between 1297 and 1304. It was intended for the daughters of wealthy Cologne merchants as well as the regional nobility and is considered one of the wealthiest women's convents in medieval Cologne. The Poor Clare Monastery was known for its spiritual role, but also for its manuscripts, the most beautiful of which were illuminated on site by Sister Loppa von Spiegel (Loppa de Speculo) around 1350.

The altar, which with a width of over 6 meters is one of the largest Cologne altarpieces of the 14th century, probably stood on the nuns' gallery in St. Clara. Since the nuns also had the permission to keep the consecrated hosts themselves, the tabernacle was built into the altar as an extraordinary solution. Around the year 1400 the altar was completely painted over for unknown reasons. Candle smoke nuisance should possibly be eliminated; there was no major damage. The new color version followed the original paintings in composition and iconography.

After the French invasion, the monastery was secularized in 1802 and the Church of St. Clara demolished two years later. The altar was saved by the Boisserée brothers and, through the mediation of Ferdinand Franz Wallraf and Sulpiz Boisserée, was installed in the Johanneskapelle in the cathedral in 1811. In the following decades the altar was restored several times. In 1820 and 1834 to 1837 the shrine box was repaired. Between 1859 and 1865, the sculptor Christophe Stephan added the missing sculptures and his son Michael also restored the color version.

The clear altar was given a new meaning when in 1908 it was given a place behind the high altar in the cathedral choir instead of the baroque altar structure. The major restoration carried out for this purpose in the years 1907 to 1909 meant, however, a deep intervention in the existence of the property. The restorer identified the overpainting from 1400, but considered it to be a paint from the early 19th century, which he therefore recommended to remove completely. Only when the removal of this layer of paint threatened to ruin the original first color version was the processing stopped. Subsequently, the “odium of the doubtful” stuck to the clear altar for decades and painting received little attention. The altar in the art bunker in the north tower hall survived the Second World War.

Only extensive restoration work between 1971 and 1982 was able to determine the extent of the two medieval layers of paint and to free the clear altar, which has been installed in the north aisles of the cathedral in the transition to the transept since 1969, from the suspicion of forgery. The two canvas doors with which the projecting central shrine can be closed have been attached to the altar again since 2007.

Stylistic classification

The altar dates from the middle of the 14th century; Around 1400 it was partially painted over , probably by the master of St. Veronica . His painting is "among the best that German art of that time has to offer." Together with the illuminations by Johannes von Valkenburg and the Cologne choir screen painting , the clear altar is considered an early key work of the Cologne school of painting . In fact, the master of the clear altar borrows numerous recognizable borrowings from painting the choir screen. The division of the painting area into tracery arcades seem to be inspired by the cathedral, which can also be demonstrated in individual tracery forms. The style of the figure design with a tube-like body in cloth-rich, but tight-fitting clothing also borrows from the choir. The master of the clear altar adapted the narrative style of painting, which was successful for the first time in the cathedral north of the Alps, for the narration of his pictures, which, however, due to the limited space, he transfers to a small group of figures. Finally, the carved figures on the clear altar with their slim, tall form, whose body slightly arches, are to be placed in the tradition of Cologne carvers, the starting point of which are the choir pillars. Individual art historians have concluded from this that the clear altar comes from the same workshop that was also active in the cathedral.

In any case, the clear altar, together with the Ursula altar from the Marienstatt abbey church and the Oberwesel gold altar, are among the most beautiful examples of high Gothic altars.

description

The clear altar consists of a cabinet with a double pair of wings. It is over three meters high and over six meters wide when open. The cabinet is made of wood and around 28 cm deep. The inner wings of the altar are also made of wood; the outer wings are constructed as a thin wooden frame covered with canvas. Presumably these belong to the oldest canvas paintings of the Gothic.

The tabernacle shrine is permanently installed in the middle and divides the image cycles. These are structured in a grid of tracery arcades, the basic dimension of which is the number twelve. The altar shows twelve saints, twelve scenes from the childhood of Jesus and twelve others from the Passion, twelve apostles and twelve relics. The wings allow three different views - the working day side, the holiday side and the high day side - whose increasingly magnificent design is intended to underline the importance of the high days. The weekday page shows muted colors, with dark green, red and - in the case of the saints depicted - a brown tint dominating. The opening of the festival shows a complete christological program, which is held in bright colors of gold and red. When fully open, the clear altar shows itself as a carved altar with set figures and reliquary busts. A bright golden color tone should reveal the closeness of the divine.

The attempt to depict the heavenly Jerusalem was recognized in the iconography of the clear altar . The intention becomes clear through the combination of all three sides of the show and the complex image structure suspended therein. Starting from the Eucharist, which is made manifest through the central tabernacle, the Franciscan ideals of poverty and chastity are brought to the fore. The holy models depicted should encourage imitation and encourage following Christ, which is formulated in Christology on the feast day page. This can ultimately - on the high festival page - lead to acceptance into the divine court visualized by the apostles, which anticipates a physical proximity to the relics of the holy virgins already in this world. “You can say: The heavenly world becomes visible to us earth children.” The donors probably influenced the image program significantly.

Weekday page

When closed, the altar shows the weekday side. In twelve arcade fields, six male and six female saints are depicted who are related to the Franciscan order or who are committed to its ideal of poverty. All figures stand on a red background decorated with stylized gold flowers and face the center of the altar - the tabernacle shrine. The saints are shown in a slightly curved posture in the slender ideal form of the high medieval painting style, which is now called International Gothic . The color tone is muted and brown overall.

In the top row, from left to right, we see Anthony of Padua as a scholar, Saint Louis of Anjou , Bishop of Toulouse, Francis of Assisi shown with his stigmata and a cross, John the Baptist carrying the Lamb Saint Nicholas of Myra and Saint Lawrence of Rome , who holds the grate of his martyrdom. Below are shown St. Mary Magdalene with the anointing vessel, Elisabeth of Thuringia , who dresses the poor, and St. Clara as the founder of the order, St. Catherine of Alexandria , who carries the wheel of torture, St. Agnes of Rome with the lamb and finally Saint Barbara of Nicomedia , who carries a tower.

Holiday page

The festive opening shows 24 scenes from the life of Jesus in 24 golden tracery arcades. The top twelve scenes are about the passion and resurrection. The lower twelve scenes tell stories from Jesus' childhood. The arcades are painted on the two outer wings, which are covered with canvas. On the inner, wooden wings, the architectural forms are made from flat frameworks. The background of all scenes is a designed gold ground, which is hallmarked in the inner fields and painted in relief in the outer fields. The arcade gussets show finely curved ornamental leaf tendrils on an alternating green and red background. Overall, a golden color impression dominates.

- 24 scenes from the life of Jesus (feast day page)

The twelve scenes of Jesus' childhood can be read from left to right and depict the following events: Annunciation to Mary, Visitation, Way to Bethlehem, Adoration of the Child, Annunciation to the Shepherds, Mary and Joseph wash the Christ Child, Adoration of the Holy Three Kings, offering in the temple, flight into Egypt, child murder from Bethlehem, return from Egypt, the twelve-year-old Jesus in the temple. The twelve overlying scenes from the Passion show: Prayer on the Mount of Olives, Jesus captured, Jesus in front of Pontius Pilate, flagellation of Christ, crowning of thorns, carrying the cross, descent from the cross, burial, resurrection, Christ in Limbo, the risen Christ and Mary Magdalene, Christ's ascension.

The paintings show a sensual style, especially idyllic in the childhood scenes, which is even more pronounced in the master from 1350 than in the master from 1400. The painter shows Joseph and Mary in intimate eye contact on the way to Bethlehem; Maria, meanwhile, in a Gothic ideal figure, whose pregnancy is only indicated by a stick on which she leans. The scene of the bath of Jesus and the adoration of the child, in which the Christ child appears to be kissing his mother from the cradle, is of seldom seen family intimacy.

The scene "Adoration of the Magi" that can be seen today is the overpainted version from around 1400. The original version from around 1350 could also be made visible through X-rays. The scenic layout of both pictures is identical; however, the older master had a more sensual narrative style. For example, he let the Christ Child sit fully clothed on the lap of his mother, who holds the boy by the shoulder as he leans toward the king.

- Scenes from the childhood of Jesus (feast day page)

High strength site

To the solemnities to have effect as possible brilliantly-solemnly when fully open, the altar, the artist has combined several representational effects: the pictures are not picturesque, but sculpturally; the architectural images are three-dimensional and gilded; In the niches, twelve relics are visibly presented in busts. In this way, the divine should not only be depicted, but to a certain extent be able to be experienced physically.

The architectural frame with the carved tracery is exemplary of the skills of the Cologne wood sculptors in the first half of the 14th century. In the upper row, the altar shows the twelve apostles as slender figures with large heads. The robes are richly pleated and set in gold. In the lower niches are set twelve busts of female saints, which contain the relics of twelve virgin companions of St. Ursula in circular openings. Some of the busts are marked with names, some of which denote the first abbesses of the monastery.

Center shrine

In the middle of the altar is the central shrine with the tabernacle . This interrupts the picture cycles and protrudes slightly. The lower half of the tabernacle case is adorned with a painting of the so-called St. Martin's Mass, which gives an indication of the shrine's Eucharistic function. In the upper half there is an open niche with a tracery arcade. It is possible that in the Middle Ages different figures - Salvator, Mother of God, crucifix - were placed in the niche, which were related to the viewing sides; today a figure of the world judge from the 19th century is inserted. In 2007 the two doors with which the central shrine can be closed were also reattached to the altar. They show a man of sorrows and a crucifixion.

The door of the Tabernakelgehäuses, the so-called Martin Mass . The rarely visualized Legend has it that Martin had met on the way to the fair to a poor man without clothing. Martin left him his and instead put on a garment that he had brought in at short notice, but which was too short for him. During the change, when Martin raised the host and showed bare arms because of the short sleeves, the assembly of believers could see a ball of fire symbolizing the divine blessing. At this moment Martin was miraculously dressed correctly and even adorned with gold bracelets. The illustration shows the moment when the saint receives the blessing of the divine fire while elevating the host.

The two canvas doors that can close the central shrine have been attached to the altar again since 2007. The upper door shows a man of Sorrows standing in a half-open sarcophagus . He is surrounded by the Arma Christi , the instruments of suffering. This depiction, which goes back to Pope Gregory I (Gregorian Man of Sorrows), was widely used as a devotional image since the 13th century. The figure below shows the crucifixion of Christ.

back

Shortly after 1900, the decision was made to free the high altar in the cathedral from its baroque structure and restore it to its medieval state. In the course of this redesign, the clear altar was set up behind the high altar, making it free in the room for the first time. In 1905, the neo-Gothic artist Friedrich Wilhelm Mengelberg was commissioned to design the back, and he used it to create one of the most recent neo-Gothic works in the cathedral. The painting shows the divine Trinity in an almond-shaped frame. This is surrounded by four seraphim . Mengelberg has depicted the four evangelists in the four spandrels .

Dating

Due to the overpainting of the altar around 1400, dating the first version proved difficult. A dendrochronological investigation in 1991 revealed the years after 1341 as the time of origin. Presumably the altar was already erected on the nuns' gallery for the consecration of the monastery church in 1347.

The two masters of the painting could only be distinguished in the course of the extensive restoration that took place between 1971 and 1982. The altarpieces were originally created between 1340 and 1360 and then painted over around 1400 for reasons unknown to us today. Both masters used the respective Gothic painting style of their time. The processing around 1400 received the original iconography and also the basic image composition. However, it is more colorful in its application of colors and shows more details and, in accordance with the style of its time, also different folds of clothing. The gilding and all gold backgrounds are works of the first master. He also took hold of the figures of the apostles, but their faces were painted over by the second master. The inside of the outer wings show the creations of the first master. The inner wings are a work of the second master from around 1400.

Seven of the figures of the twelve apostles date from the Middle Ages; two of them are in the original in the Museum Schnütgen and have been replaced by copies. Five figures were added in 1881 by Christoph Stephan as part of the restoration in the 19th century. Eleven of the reliquary busts for Ursula's entourage have survived from the Middle Ages; Cathedral archivist Rolf Lauer was only able to rediscover one of them in Caracas in 2005 . A reliquary bust on the left was recreated in the 19th century.

See also

literature

- Christa Schulze-Senger, Wilfried Hansmann: The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral, documentation of the investigation, conservation and restoration, Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft, Worms 2005, ISBN 3-88462-211-0

- Christa Schulze-Senger: The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral. Comments on the conception, technical structure, design and current restoration of a large Cologne altarpiece (as of 1977) , in: Kölner Domblatt 1978, pp. 23–37.

- Alexandra König: The Beginnings of Cologne Panel Painting , Diss. Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf 2001 Diss.

- Katharina Ulrike Mersch: Social dimensions of visual communication in high and late medieval women's communities, pens, women's choirs and monasteries in comparison , V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-89971-930-7

- Norbert Wolf: German carved retable of the 14th century (monuments of German art), Berlin: German publishing house for art history 2002, ISBN 978-3-87157-194-7

Web links

- koelner-dom.de: Site plan in the cathedral

- sehepunkte.de: Review of The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral

Individual evidence

- ↑ Barbara Schock-Werner quoted. According to Aachener Zeitung: Altar panels are returning after more than 100 years

- ↑ The lion depiction on the altar cloth of the offering scene is interpreted as her coat of arms. Alexandra Koenig: The Beginnings of Cologne Panel Painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (Diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 135.

- ↑ Ulrike Mersch 2012, Section IV.2.2: The Poor Clares in St. Klara in Cologne, pp. 256–279

- ↑ collections.vam.ac.uk: Manuscript Loppa de Speculo

- ↑ Wolfgang Herborn, Carl Dietmar: Cologne in the late Middle Ages, 1288–1512 / 13, Cologne 2019, p. 478

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (Diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 136ff.

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 130.

- ↑ Schulze-Senger, Hansmann 2005

- ↑ Schulze-Senger, Hansmann 2005

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 126.

- ↑ Schulze-Senger, Hansmann 2005

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar

- ↑ Christa Schulze-Senger: The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral. Comments on the conception, technical structure, design and current restoration of a large Cologne altarpiece (as of 1977), in: Kölner Domblatt 1978, pp. 23–37.

- ↑ www.aachener-zeitung.de: Altar panels are returning after more than 100 years

- ↑ Norbert Wolf : sehepunkte.de: Review of The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc p. 145

- ^ Norbert Wolf: German carving retable of the 14th century, German publishing house for art history, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-87157-194-7

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar

- ↑ Barbara Schock-Werner: Domgeschichten, with retired cathedral master builder through the Cologne Cathedral , Cologne 2020, p. 88

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (Diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 127f

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 132ff

- ↑ Barbara Schock-Werner: Domgeschichten, with retired cathedral master builder through the Cologne Cathedral , Cologne 2020, p. 88

- ↑ Renate Schumacher-Wolfgarten: By women for women. Searching for traces at the Cologne Clear Altar, in: Hans-Rudolf Meier, (Ed.), For earthly fame and heavenly reward. Founder and client in medieval art. Beat Brenk on his 60th birthday , Berlin 1995, p. 269ff.

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar festival opening

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar Fsttagsopening

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar high festival opening

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (Diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 127f

- ↑ Alexandra Koenig: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Düsseldorf 2001 (Diss.), Uni-duesseldorf.de: Doc , p. 129

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Festtagsseite

- ↑ aachener-zeitung.de: Altar panels are returning after more than 100 years

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Martinsmesse

- ^ Cologne Cathedral: Altar panels return after more than 100 years [1] Aachener Zeitung, December 7th, 2007

- ↑ koelner-dom.de: Clear altar back

- ↑ Investigation by P. Klein on the back walls of the central shrine. Cf. Alexandra König: The Beginnings of Cologne Panel Painting , Diss. Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf 2001 Diss. , P. 141.

- ↑ Alexandra König: The beginnings of Cologne panel painting , Diss.Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf 2001 Diss. , P. 130f, Christa Schulze-Senger, Wilfried Hansmann: The Claren Altar in Cologne Cathedral, documentation of the investigation, conservation and restoration, Worms 2005 , P. 32

- ↑ Barbara Schock-Werner: Cathedral stories, with the master builder a. D. by the Cologne Cathedral, Cologne 2020, p. 90f