Composition (music)

As a composition (from Latin componere ' to assemble') (outdated: Tonwerk ) is called:

- the creation, elaboration and authorship of a musical work of art ( composing ), as well as

- the completed piece of music ready for performance itself, especially its musical structure.

As a rule, it is a traditional work by a composer that offers the possibility of repeatable execution. Are opposite terms

- Oral tradition : A musical work cannot be traced back to a person, but is passed on as a common good and is sometimes subject to change;

- Improvisation : Music arises in the playing process itself and is not intended to be repeated (on the other hand, the fantasy is a separate form of composition);

- Interpretation : A work available as a composition is performed by an interpreter (singer, musician).

In earlier centuries the current composition theory ( harmony , counterpoint , form theory ) was mostly passed on by experienced composers in a teacher-student relationship. Today it is a ten-semester main subject at European music academies .

Composition of "classical" music

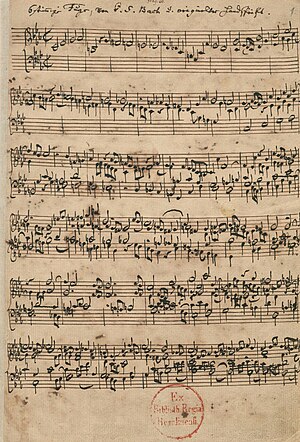

Above all, composition is the creative process that is characteristic of “classical” music (in the sense of art or serious music ). It describes the invention of a musical work and the fixation of it by the composer . The specifications made by the composer vary depending on the parameters and also from work to work. In classical-romantic music, the pitches are precisely defined, the tone durations and the resulting rhythm can be precisely determined in relation to the basic tempo. These can thus be referred to as primary parameters or composition categories. Dynamics and articulation can also be prescribed in a very differentiated manner, but like the primary parameters they cannot be represented in precise values in the notation and thus secondary parameters or composition categories. The interpreter is responsible for interpreting the resulting spaces. This also applies to the tempo , as there is no corresponding absolute tempo perception that actually interprets deviations from a prescribed tempo (e.g. in beats per minute ) as deviations from the composition, as long as the tempo impression ("fast", "Moderate", "slow") changes. The choice of line- up and instrumentation is also in the hands of the composer . As the symphonic orchestra became increasingly differentiated, in the course of the 19th and 20th centuries these also increasingly took on the character of a composition category, although it is mostly a process that precedes the actual composition (choice of line-up) or that follows it (instrumentation).

The concentration of the musical creative process on the composer and thus on an individual is a decisive characteristic of classical music, which is decisive for its historical development. It is a prerequisite for the increasing admiration of the composer as a " genius " since the 19th century , for the transmission of a growing canon of "masterpieces" and finally for the increasingly strict separation and specialization of composer and interpreter. Newer, non-individualistic approaches focus on artistic practices which, although individual forms, have a historical and social anchorage. Composition is therefore seen as an intelligent and creative act of social practice.

Paradoxically, however, precisely these developments in the 20th century led to the composer becoming less important than the interpreter, as the interpreter can fall back on the canon of generally recognized “masterpieces” with which the contemporary composer has to compete. The term “classical music” thus increasingly stood for the transformation of historically traditional music into current music events and the performer became its actual bearer. The composers found their niches only in experiments, which differed further and further from the historical material (which also concerned the above-mentioned characteristics of “composing” and occasionally questioned them), but were thus pushed into specialized concert series and festivals. As a result, the audience has split into listeners of “classical” and “new” music . Since the sound recording in turn makes a “canon” of “master interpretations” available, the performers today see themselves in a situation comparable to that of composers, which leads all “classical music” into stagnation, from which it is questionable whether it will free itself can.

Composition processes are the subject of empirical (musicological, psychological and sociological) research. A distinction is made between retrospective and in actu documentation and analyzes of compositional processes.

Composition in rock music and jazz

Outside of “ classical music ”, the composition and the composer are of comparatively less importance, as numerous traditional tasks of the composer are carried out in a division of labor. In jazz, for example, only the melody and the harmonic framework of a piece are usually referred to as the composition, while the arrangement and improvisation also play an important role in the audible end result (a constellation that was used in European art music up until the middle of the Baroque era could occur). Important jazz composers such as Duke Ellington , Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter are accordingly in their own shadow as performing musicians. In contrast to classical music, the historical development of jazz is also shaped by performing musicians and not by composers.

In rock music , composition, arrangement and performance are usually a collective process that can never be completely broken down into its details, the result of which is only intended for performance by its creator and not for transmission to other performers, who therefore do it in the “classical” sense here also not there. In this case, notes are often only required in a reduced form or not at all, especially when working closely with studio recordings, which can make classical notation superfluous.

The different importance of composing in “light” and “serious music” sometimes leads to inconsistent standards in an appreciative aesthetic comparison.

See also

literature

- Markus Bandur: Composition / Komposition [1996], in: Concise dictionary of musical terminology [loose-leaf edition], Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden, later Stuttgart, 1971–2006; DVD, Stuttgart 2012; Republished in: Terminology of Musical Composition , edited by Hans Heinrich Eggebrecht, Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1996 (= Concise Dictionary of Musical Terminology, Special Volume 2, pp. 15–48) ISBN 3-515-07004-4 .

- Norbert Jürgen Schneider : Composing for film and television Schott 1997 ISBN 3-7957-8708-4 .

- Clemens Kühn : Composition history in annotated examples Bärenreiter 2008 ISBN 3-7618-1158-6 .

- Paul Hindemith : Instruction in Tonsatz Schott 1984 ISBN 3-7957-1600-4 .

- Knud Jeppesen: Counterpoint. Textbook of classical vowel polyphony Breitkopf & Härtel 1985 ISBN 3-7651-0003-X .

- Matthias Schmidt : Composition. In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 3, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2004, ISBN 3-7001-3045-7 .

- Marcello Sorce Keller : "Siamo tutti compositori. Alcune riflessioni sulla distribuzione sociale del processo compositivo" Swiss Yearbook for Musicology , New Volume XVIII (1998), pp. 259-330.

- Tasos Zembylas , Martin Niederauer: Practices of composing: sociological, knowledge-theoretical and musicological perspectives. Wiesbaden, 2016.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tasos Zembylas (Ed.): Artistic Practices. Social Interactions and Cultural Dynamics. London, 2014; Tasos Zembylas , Martin Niederauer: Practices of composing: sociological, knowledge-theoretical and musicological perspectives. Wiesbaden, 2016.

- ↑ Collins, Dave (Ed.): The act of musical composition. Studies in the creative process. Farnham, 2012; Donin, Nicolas / Féron, Francois-Xavier: “Tracking the composer's cognition in the course of a creative process: Stefano Gervasoni and the beginning of Gramigna”. In: Musicae Scientiae, 0/2012, 1-24; Tasos Zembylas , Martin Niederauer: Practices of composing: sociological, knowledge-theoretical and musicological perspectives. Wiesbaden, 2016.