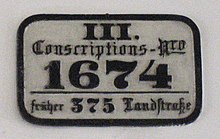

Conscription number

Conscription numbers are a method of numbering houses that was introduced in the Habsburg Monarchy . They are series of numbers that were used in the 18th and 19th centuries to number houses and properties for administrative purposes. These numbers were primarily used to supplement the army, to collect taxes and to perform statistical tasks (population statistics, building statistics, etc.). But they also offered a certain amount of support in naming locations. If number systems, which are primarily intended for orientation (sorted by streets, etc.) are not available, conscription numbers are still used today for orientation. In official documents, the orientation number can be the generic term for house number and conscription number.

The difference between conscription numbers and orientation numbers is that conscription numbers do not always allow conclusions to be drawn about the location of a building, but are primarily assigned according to other criteria (date of building permit, etc.). Orientation numbers (often called house numbers), on the other hand, are assigned primarily for each street or town with the purpose of making it easier to find houses, apartments (addresses), the delivery of mail, etc. Since conscription numbers originally had to be affixed to the buildings just like orientation numbers, conscription numbers were also referred to as house numbers. The function of conscription numbers to provide a numbering scheme for official tasks exists in parallel to the allocation of house numbers in the 21st century, only the word conscription number is no longer used for this, but other terms (serial number, register number, file number, deposit number, etc.). One of the best-known examples of a conscription number is the brand name 4711 from Cologne.

development

The first general assignment of conscription numbers in Austria took place during the reign of Empress Maria Theresa as part of the introduction of numbering sections . The numbers were mostly assigned in the order in which the buildings were erected. Houses lying next to each other on a street could have very different numbers depending on the construction time. The changeover met with unease among the population, which Maria Theresa tried to dispel by including her own residence, the Hofburg , in the numbering, with the conscription number 1. It cannot be assumed that the conscription numbers from that time 1770 later survived as house numbers or as deposit numbers in the land register. In practice, especially in larger towns, this will only very rarely be the case. In Vienna the numbering scheme was renewed after 25 years, in 1795. For houses in the city center, numbers were provided in red, in the suburbs, numbers in black. In the first decades of the 19th century (in Vienna from 1821), a third numbering was carried out as part of the work on the re-creation of the land tax register, and another numbering during the creation of the land register in 1874, from which the deposit figures of the land register resulted. A building could therefore have five different conscription numbers over a period of just over a hundred years. This is also because the original purpose of the conscription numbers, to record inhabited houses for tax and military purposes, did not have to take into account the land on which these houses were located (several properties can belong to one house), while the later introduced detailed property tax records and the land register, which was introduced later, were primarily aimed at the precise representation of the properties.

The multiple numbering within a few decades led to ambiguities that were reflected in linguistic usage. The term house number will also be used for assumptions into the 21st century, as a mere example instead of an exact specification. The phrase “give a house number” can mean the opposite of an exact description in everyday language in Austria, namely a rough estimate, an indication of something, any number.

In both the Czech Republic and Slovakia , the conscription numbers introduced in the Habsburg Empire are still used today as house numbers and are also entered in ID cards. In these two countries it often happens that two numbers are attached to houses: the conscription number and the orientation number.

Loss of meaning

The conscription numbers were mainly intended for administrative purposes and were not very useful for orientation. After their introduction, they made it easier (together with other information, such as house signs, street information, etc.) to find your way around larger towns, but never received the great practical significance in everyday life that the house numbers were given. Later, conscription numbers - in their function as orientation aids - were almost completely replaced by house numbers (orientation numbers) that are more useful in everyday life. Conscription numbers can still be found on old buildings in addition to house numbers. In small towns, especially in smaller scattered settlements such as hamlets or residential areas , conscription numbers (e.g. the number of deposits in the land register, the consecutive number of a building directory) may have retained the function of house numbers. As a rule, however, separate house numbers are also assigned in such localities (in order, for example, to be able to take into account new residential buildings, but also the abandonment of old houses or farms in a comprehensible scheme). In these cases, the place name corresponds to the street name when specifying the address.

- House numbers: old conscription numbers and new orientation numbers (main street in Guntramsdorf )

disadvantage

If conscription numbers are used as the only house numbers, this results in an obvious, serious disadvantage: the house numbers are not consecutive and not even uniformly ascending or descending along a street, but rather mixed up in a colorful jumble: For example, the house can be next to house no.108 # 167, followed by # 74.

Such irregular number sequences can arise from the fact that the houses were numbered in their order when the numbers were assigned, but then later newly built houses had to be given a higher number. If, for example, there was a gap between no.120 and no.121 in the allocation of the numbers that was later built on, the new house received the first free number: If the whole place had 231 houses and thus the highest number was 231 the new house had to get the number 232, although it was between number 120 and number 121. The same applies to houses that were later divided. Here one half could still carry the old number, but the second half could get a new one. The system became even more confusing when the vacant numbers of demolished houses were reassigned elsewhere.

Such numbering, which did not correspond to the order of the houses, was very impractical in everyday life, as one could not simply follow the course of the house numbers to the house sought. In the above example, house no. 232 is not next to 231, but at a completely different location in the city. Therefore, in some places the houses were sometimes renumbered several times in the past in order to get a regular number sequence again.

Since each conscription number is only assigned once within a town, house numbers that come from a conscription numbering scheme can also reach higher values and contain three to four digits.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ordinance of the Federal Minister of Economics and Labor on the content and structure of the information in the address register and the reimbursement of costs for queries and extracts from the address register (Address Register Ordinance - AdrRegV). Austrian Federal Law Gazette 2005 Part II No. 218 .

- ↑ Gerhard Robert Walter of Coeckelberghe-Dützele: The imperial palace in Vienna. 1853, page 1 (or 15 of the online edition).

- ^ Preservation of the house number in the city of Vienna and in the suburbs. Government ordinance to the Magistrate of March 9th, announcement of March 17th, 1795. Renewed by ordinance of the Viennese Magistrate of September 12th, 1795 . Volume 7, pages 60-61. In: His Majesty Franz the First political laws and ordinances for the Austrian, Bohemian and Galician hereditary countries. (so-called PGS - Political Law Collection). From the k. k. Hof- und Staats-Aerial-Druckerey. Vienna 1816. Year 1795. Volume 6. Pages 144–145.

- ↑ Conscription and Recruiting Patent : Patent Franz II. No. 4 of October 25, 1804. In: Seiner k. k. Majesty Franz des Zweyten political laws and ordinances for the Austrian, Bohemian and Galician hereditary countries. Volume three and twentieth which contains the ordinances from October 1st to December last, 1804. Vienna 1807. K. k. Hof- und Staats-Druckerey. (Political laws and ordinances 1792–1848, so-called PGS - Political Law Collection) Page 3 to Page 131

- ↑ Using the example of the address Köllnerhofgasse 3 in the inner city of Vienna, whose house received the conscription numbers 759, 1379, 784, 738 and 647 over the decades: Anton Tantner: Die Hausummerierungen . In: Sylvia Mattl-Wurm, Alfred Pfoser: The measurement of Vienna. Lehmann's address books 1859–1942. Metroverlag Vienna 2011. ISBN 978-3-99300-029-5 , corrected ISBN 978-3-99300-029-5 . Page 262.

- ^ Robert Sedlaczek: Dictionary of Viennese. Haymon, Vienna 2011. ISBN 978-3-85218-891-1 . P. 124.

- ↑ Otto Back u. A .: Austrian dictionary. Edited on behalf of the Federal Ministry for Education, Art and Culture. 42nd edition. Österreichischer Bundesverlag Vienna 2012. ISBN 978-3-209-07361-7 . P. 321.

- ↑ Wolfgang Teuschl : Wiener Dialekt-Lexikon. Residenz Verlag, Vienna 2011. ISBN 978-3-7017-1464-3 . P. 137.

- Conscription numbers and orientation numbers (Josefigasse in Guntramsdorf)