Cowherd and weaver

Cowherd and weaver ( Chinese 牛郎 織女 / 牛郎 织女 , Pinyin niúláng zhīnǚ , Jyutping ngau 4 long 4 zik 1 neoi 5 ) is a Chinese folk tale . It describes the forbidden love story between Zhinü ( 織女 / 织女 ), the weaver that the star Vega symbolizes and Niulang ( 牛郎 ), the cowherds of the star Altair symbolizes. Their love was not allowed, so they were banished to opposite sides of the "Silver River" ( 銀河 / 银河 , yínhé , Jyutping ngan 4 ho 4 , old Chinese name for the Milky Way ). Once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month ( 七夕 , qīxī - "The Night of the Seven"), a flock of magpies forms a bridge ( 鵲橋 / 鹊桥 , quèqiáo , Jyutping coek 3 kiu 4 - "Elsterbrücke") over the "river “(Milky Way) to reunite the lovers for a day. There are many variations on this story. The first known reference to this myth dates back over 2,600 years and appeared in a poem in the Chinese Book of Songs .

The folk tale of the “ cowherd and the weaver ” has been celebrated in China at the Qixi festival since the Han period . It is also celebrated in Japan for the Tanabata Festival and in Korea for the Chilseok Festival. The story is one of the four great Chinese folk tales. The other three folk tales are The Legend of the White Snake , The Story of Meng Jiang Nü and Liang Shanbo, and Zhu Yingtai .

Literary interpretations

The folk tale cowherd and weaver has been alluded to in many literary works. One of the most famous is the following poem by Qin Guan (1049–1100) during the Song Dynasty :

"鵲橋仙

- 纖 雲 弄 巧 , 飛星 傳 恨 , 銀漢 迢迢 暗 渡. 金風玉 露 一 相逢 , 便 勝 卻 人間 無數. 柔情似水 , 佳期 如夢 , 忍 顧 鵲橋 歸路. 兩 情 若是 久 長 時 , 又 豈 在 朝朝暮暮.

Meet over the Milky Way

- Through the different shapes of the delicate clouds, the sad news of the falling stars, a quiet journey over the Milky Way, a meeting of the cowherd and the weaver in the midst of the golden autumn wind and the glittering dew, darken the countless encounters in the everyday world. The feelings as soft as water, the ecstatic moment as unreal as a dream, how can one have the heart to walk back onto the bridge of magpies? If the two hearts are forever united, why do the two people have to stay together - day after day, night after night? "

Influence and variations

The story is popular in different variations in other parts of Asia as well. In Southeast Asia the story flowed into a Jataka , the detailed story of Kinnari Manohara, the youngest of the seven daughters of the Kinnara King, who lives on Mount Kailash and falls in love with Prince Sudhana. In Sri Lanka a different version of Manoharalegende is popular in the Prince Sudhana a Kinnari is, who was shot before the Sakra , the Buddhist equivalent of the Jade Emperor , is revived.

In Korea, the story revolves around Jingnyeo, a weaver who falls in love with Gyeonu, a shepherd. In Japan the story is about a romance between deities, Orihime and Hikoboshi. In Vietnam, the story is known as Ngưu Lang Chức Nữ and revolves around Chức Nữ and Ngưu Lang.

Cultural references

In his novel Contact, Carl Sagan refers to the Chinese folk tale cowherd and weaver . This story and the Tanabata festival also form the basis for the Sailor Moon side story entitled Chibiusa's Picture Diary - Beware the Tanabata! , in which both Vega and Altair appear. The post-hardcore band La Dispute named their first album Somewhere at the Bottom of the River Between Vega and Altair after the story and part of the album was based on it. The Japanese computer role-playing game Bravely Second: End Layer also used the names Vega and Altair for a pair of plot-related characters who shared a mutual affection years before the game's history.

The Chinese relay satellite Elsternbrücke got its name after this story.

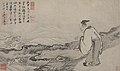

Picture gallery

Zhinü and shuttle - Ming , Zhang Ling before 1529

Zhinü crosses the “Heavenly River” (Milky Way) - Gai Qi 1799

The creation of the "Sky River " (Milky Way) - Ming period , Guo Xu 1503

Zhinü - Decoration of the Muxuyuan subway station ceiling, Nanjing 2010.

The reunion at the "Magpie Bridge" walkway of the New Summer Palace , Beijing .

Web links

- The Tale of the Cowherd and Weaver (Encyclopedia of Taiwan) (Chinese)

- Origin of the Qixi festival - cowherd, weaver and Elsterbrücke (web archive) (Chinese)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Ju Brown, John Brown: China, Japan, Korea: Culture and customs, BookSurge, North Charleston, 2006, ISBN 1-4196-4893-4 , p. 72

- ↑ Lai, Sufen Sophia (1999). "Father in Heaven, Mother in Hell: Gender politics in the creation and transformation of Mulian's mother". Presence and presentation: Women in the Chinese literati tradition. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999, ISBN 0-312-21054-X , p. 191

- ↑ Virginia Schomp: The ancient Chinese, Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, New York, 2009, ISBN 0-7614-4216-2 , p 89

- ↑ Virginia Schomp: The ancient Chinese, Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, New York, 2009, ISBN 0-7614-4216-2 , S. 70th

- ^ Wilt L. Idema, "Old Tales for New Times: Some Comments on the Cultural Translation of China's Four Great Folktales in the Twentieth Century" (PDF). Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies, 2012, 9 25–46. Archive version (PDF) of October 6, 2014, p. 26

- ^ Qiu 2003, 133.

- ^ Cornell University (2013). Southeast Asia Program at Cornell University: Fall Bulletin 2013 . P. 9.

- ↑ Jaini, Padmanabh S. (ed.) (2001). Collected Papers on Buddhist Studies

- ↑ http://www.lankalibrary.com/rit/kolam.htm

- ↑ https://www. britica.com/topic/Sandakinduru-Katava

- ↑ https://chulie.wordpress.com/2011/11/07/kataluwa-purvaramaya-temple-tragic-deterioration-of-a-country-treasure/

bibliography

- Ju Brown, John Brown: China, Japan, Korea: Culture and customs . BookSurge, North Charleston 2006, ISBN 1-4196-4893-4 .

- Wilt L. Idema : Old Tales for New Times: Some Comments on the Cultural Translation of China's Four Great Folktales in the Twentieth Century . In: Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies . 9, No. 1, 2012, pp. 25-46.

- Sufen Sophia Lai: Father in Heaven, Mother in Hell: Gender politics in the creation and transformation of Mulian's mother . In: Presence and presentation: Women in the Chinese literati tradition . St. Martin's Press, New York 1999, ISBN 0-312-21054-X .

- Xiaolong Qiu: Treasury of Chinese love poems . Hippocrene Books, New York 2003, ISBN 978-0-7818-0968-9 .

- Virginia Schomp: The ancient Chinese . Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, New York 2009, ISBN 0-7614-4216-2 .