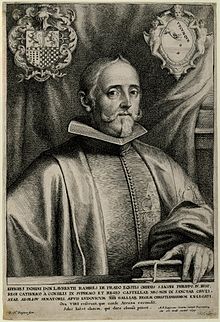

Lorenzo Ramírez de Prado

Lorenzo Ramírez de Prado (born August 9, 1583 in Zafra , Extremadura , Spain ; † July 15, 1658 ) was a Spanish humanist , author, Castilian politician, and book and art collector. His father was Alonso Ramírez de Prado , Minister of Finance under Philip III. of Spain, who died in prison on July 15, 1608 under suspicion of fraud.

Lorenzo is one of the most famous humanists of the Siglo de Oro , the "Golden Century" of Spanish art and culture. After studying in Salamanca with Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas, called El Brocense (1523–1601), he was a. a. Familiar del Santo Oficio (member of the Holy Inquisition, 1626), member of the noble Santiagoorden and finally Oficial del Santo Oficio (1638). In addition, he was politically active in the Castilian Cortes .

The writers Lope de Vega and Luis de Góngora were among his circle of friends .

His work at the Santo Oficio meant that he was in the service of the Spanish Inquisition , even though his teacher, El Brocense, was three times among the victims of this institution; he even died in custody at the age of 78. Since Lorenzo R. de Prado at the Inquisition a. a. was concerned with the review, sifting and cleaning of politically, religiously or morally disreputable literature, at the end of his life his collections comprised numerous titles and works of art that had fallen victim to censorship and that he was only allowed to own with a papal license. Some of his collector's items (books and paintings) were therefore not for sale after his death and eventually found their way into state collections in all kinds of detours.

One of the best-known pieces in his collection is one of the two handwritten versions of the Historia del Pirú des Martín de Murúa , the so-called Getty-Murúa , which came from there to the library of the Colegio Mayor de Cuenca in Salamanca .

literature

- Michael Scholz-Hänsel: Inquisition and Art: Convivencia in Times of Intolerance . Berlin: Frank & Timme 2009.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Scholz-Hänsel p. 240 f.

- ↑ In Spain, as in many other European countries, whether Protestant or Catholic (France, England, Geneva, Venice, etc.), all works intended for printing, increasingly since 1558 , had to be submitted to the state censorship authority, which checked the content for political and religious deviations examined; After the publication, this applied again to the printed edition from the church. Forbidden printing (!) Works were included in the index of forbidden books ( the index ) compiled since 1559 . The censorship laid the foundation for many of today's national libraries with the mandatory deposit ( deposit copy ); on censorship in Spain: Horst Rabe: The Iberian States in the 16th and 17th centuries. In: Handbook of European History. Edited by Theodor Schieder. Vol. 3. Stuttgart: Union 1971. pp. 581-662. P. 621 f. - On censorship in Spanish America in general: Bernard Lavallé: Kulturelles Leben. In: Handbook of the History of Latin America. Vol. 1, p. 510 ff. - On the relationship between state censorship and the church inquisition, see the interview with Rolena Adorno in http://www.librosperuanos.com/archivo/rolena-adorno.html

- ↑ Rector of the Jesuit College in Salamanca was since 1598 José de Acosta (1539-1600), colonial critic and historian, who in his Historia natural y moral de las Indias ( 1590 ) the oldest report on the New World in comparison to the old and on the Western South America delivered; for the Colegio Mayor de Cuenca in Salamanca see http://campus.usal.es/~bgh/800/exlibris/c/colemayo.htm ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ramírez de Prado, Lorenzo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish humanist, author and politician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 9, 1583 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Zafra , Extremadura , Spain |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 15, 1658 |