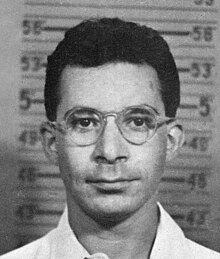

Louis Slotin

Louis Alexander Slotin (born December 1, 1910 in Winnipeg , Manitoba , † May 30, 1946 in Los Alamos (New Mexico) ) was a Canadian physicist and chemist . He assembled the core of the first atomic bomb and was the second person to die as a result of a self-inflicted nuclear accident .

Early years

Louis Slotin studied in Winnipeg and received his doctorate in London in 1936 on a subject in physical chemistry .

From 1937 to 1942 he worked and researched at Chicago University . There he helped build an electron cyclotron and was involved in the Chicago Pile . Together with Earl Evans, he was able to prove that animal cells are able to synthesize hydrocarbons from carbon dioxide. For this he used the radioactive carbon isotope 11 C with a half-life of 20 minutes, which he synthesized in the cyclotron.

From 1942 he worked on the Manhattan Project , the aim of which was to develop an atomic bomb. As part of this project, he worked on the production of plutonium in Oak Ridge until 1944 .

Time in Los Alamos

In December 1944 he moved to Los Alamos , where he was tasked with measuring the critical mass of fissile materials (for example uranium or plutonium ).

Slotin was involved in assembling the explosive device for the first atomic bomb test on July 16, 1945.

In September 1945 Harry Daghlian , one of his closest colleagues, died of a fatal radiation dose of 5.1 Sievert received in the wake of an accident while handling the core of a plutonium bomb. The aim of these experiments was to determine the critical mass of plutonium configurations with arrays of neutron reflectors, in this case pieces of tungsten carbide , one of which accidentally fell on the plutonium core. Because of their dangerousness, the experiments were also called " tickling the dragon's tail ".

After the war ended, Slotin planned to return to Chicago to continue his biophysical research. Because of his special knowledge in handling fissile material, however, he was not allowed to go before he had trained a successor.

Nuclear accident

On May 21, 1946, Slotin conducted a fateful experiment in the presence of seven colleagues, similar to the one to which his colleague and friend Daghlian had already fallen victim. He wanted to show his colleague Alvin Graves how to carry out criticality experiments. Two hemispherical shells made of beryllium were arranged around a plutonium core and Slotin tried to bring the hemispherical shells so close together that a chain reaction was triggered. Beryllium reflects the neutrons and thus intensifies the chain reaction. To do this, he tilted the upper hemisphere shell with his left thumb, which he had inserted into a thumb hole, and held a small gap open between them with a screwdriver that he had inserted between the two hemispherical shells. To do this, he removed the otherwise used spacers that would have prevented the shells from colliding. He intended to slowly reduce the distance by turning the screwdriver until the desired effect could be seen. At 3:20 p.m., however, the screwdriver slipped from him and the upper hemispherical shell fell onto the lower one, promptly making the arrangement overly critical . The colleagues saw a blue glow and felt a heat surge. Slotin also felt a sour taste in his mouth and a burning sensation in his left hand. Involuntarily he jerked his hand upwards, whereby the two hemispherical shells separated again and the chain reaction was ended. The supercritical excursion , however, was terminated by the thermal expansion of the apparatus.

Slotin had received a lethal radiation dose of 21 Sievert in the form of gamma and neutron radiation in the short time that the arrangement was supercritical . He was immediately admitted to the hospital, where he died of radiation sickness on May 30, 1946 . The other seven people who were in the room also received high doses of radiation (from an estimated 3.6 Sv to 0.3 Sv).

The plutonium core was the same one that had already become Daghlian's undoing. The core was then nicknamed " Demon Core ".

reception

The first official version of the accident portrayed Slotin as a hero who saved the lives of his colleagues by tearing up the upper beryllium hemisphere. Robert B. Brode, one of the leading researchers in Los Alamos, pointed out, however, that Slotin should have used spacers to prevent the two hemispheres from touching and that his negligence put his colleagues' lives in danger in the first place.

In 1948, Slotin's colleagues in Los Alamos and Chicago founded the Louis Slotin Memorial Fund, which was used to finance lectures by well-known scientists until 1962.

The 1955 novel The Dexter Masters Accident tells the last days of the life of a nuclear scientist who received a fatal dose of radiation, and takes up the story of Louis Slotin.

In the 1989 film Die Schattenmacher , the character of Michael Merriman is based on the historical figure of Louis Slotin.

In the series Stargate SG-1 , the accident situation was processed in a modified manner in episode 21 of season 5 .

The city of Winnipeg named a park after Slotin in 1993. On April 27, 2002, an asteroid was named after Slotin: (12423) Slotin .

Robert Jungk describes the accident in 1956 in his book “Heller als Tausend Sonnen”.

Fonts (selection)

- The Systems d- (NH4) 2C4H4O6-d-Li2C4H4O6-H2O and d- (NH4) 2Li2 (C4H4O6) 2-1- (NH4) 2Li2 (C4H4O6) 2-H2O . University of Manitoba, 1933 - Dissertation (M.Sc.)

- The Preparation of Racemic Tartaric Acid . In: Journal of the American Chemical Society . Volume 55, number, 6, 1933, pp. 2604-2605, doi : 10.1021 / ja01333a505 - with Alan Newton Campbell and Stewart A. Johnston

- The Systems (a) Ammonium d-Tartrate-Lithium d-Tartrate-Water, and (b) Ammonium Lithium d-Tartrate-Ammonium Lithium l-Tartrate-Water . In: Journal of the American Chemical Society , Volume 55, Number 10, 1933, pp. 3961-3970, doi : 10.1021 / ja01337a008 . - with Alan Newton Campbell

- The Utilization of Carbon Dioxide in the Synthesis of α-Ketoglutaric Acid . In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry . Volume 136, 1940, pp. 301-302, PDF . - with Earl Alison Evans

- The Role of Carbon Dioxide In The Synthesis of Urea in Rat Liver Slices . In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry . Volume 136, 1940, pp. 805-806, PDF . - with Earl Alison Evans

- Carbon dioxide utilization by pigeon liver . In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry . Volume 141, 1941, pp. 439-450, PDF . - with Earl Alison Evans

- Assimilation of radioactive carbon from C11O2 by various tissue preparations . In: Federation Proceedings . Volume 1, 1942, p. 109 - with Earl Alison Evans and Birgit Vennesland

- Carbon Dioxide Assimilation In Cell-Free Liver Extracts . In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry . Volume 143, 1942, p. 565, PDF . - with Earl Alison Evans and Birgit Vennesland

- The Mechanism Of Carbon Dioxide Fixation In Cell-Free Extracts Of Pigeon Liver . In: The Journal of Biological Chemistry . Volume 147, 1943, pp. 771–784, PDF - with Earl Alison Evans and Birgit Vennesland

- Method of dissolving uranium metal - U.S. Patent No. 2823977, August 3, 1944, (online) .

See also

literature

- HL Anderson, A. Novick, P. Morrison: Louis A. Slotin 1912-1946 . In: Science . Volume 104, number 2695, August 23, 1946, pp. 182-183, doi : 10.1126 / science.104.2695.182 .

- Barbara Moon: The nuclear death of a nuclear scientist . In: MacLean's Magazine . Volume 74, Number 2, 1961, excerpt .

- Martin Zeilig: Dr. Louis Slotin and "The invisible killer" . In: The Beaver . Volume 75, Number 4, 1995, pp. 20-26.

- [Anonymous]: Louis B. Slotin . In: Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Volume 1, Number 12, June 1, 1946, ( online ).

Web links

- Larry Lavitt: Dr. Louis Slotin Memorial .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Chicago Pile 1 Pioneers, Argonne Lab

- ↑ Review of Criticality Accidents, Los Alamos National Laboratory, PDF file, 3.8 MB , 2000, p. 75. As well as the reminder page for Daghlian

- ↑ Lillian Hoddeson et al. a. Critical Assembly , p. 342. It cites David Hawkins Project Y. The Los Alamos Story , Los Angeles 1983

- ↑ reminder page Slotin ( Memento of 16 May 2008 at the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Hoddeson et al. a. Critical Assembly , loc. cit.

- ↑ Review of criticality accidents, loc.cit., P. 75.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Slotin, Louis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Slotin, Louis Alexander (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Canadian physicist and chemist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 1, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Winnipeg , Manitoba |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 30, 1946 |

| Place of death | Los Alamos (New Mexico) |