Macunaíma - The hero without any character

Macunaíma - The hero without any character (original title: Macunaíma: o herói sem nenhum CARATE r) is a 1928 published novel of the Brazilian writer Mário de Andrade .

action

The hero is born by an Indian woman of the Tapanhumas in a hut in the jungle, somewhere in northern Brazil on the Uraricoera River , near the São Joaquim Fort . In the first few years he said little, except: “Ai! que preguiça! ”(“ Oh, this laziness! ”) So he is lazy and voracious, and also lustful: He first sleeps with one of his brother Jiguê's companions, and when Jiguê drives it away because he notices it and takes a new one , the protagonist also sleeps with his new companion. Occasionally, however, he does go hunting and on one such occasion shoots his mother, whom he believed to be a doe because of a spell of the forest spirit Appendixá . After a period of mourning, Macunaíma, Jiguê and his companion, the beautiful Iriqui, who does makeup all day, and Macunaíma's older brother Maanape, who is a great magician, go out into the world.

In the jungle they meet Ci, the mother of the jungle, who belongs to the lonely women, the tribe of the Icamiabas , the legendary Amazon warriors of the rainforest, which you can see on her right breast, which is very flat and dry. Macunaíma wants to sleep with her, but Ci does not want to, a fierce fight breaks out in which Macunaíma would have lost out if his brothers had not helped him knock the Ci unconscious so that Macunaíma can rape her, making him emperor of Forest will.

Ci and Macunaíma live together from then on: Ci leads the women into battle and Macunaíma rests during the day so that he is not too tired for the love games with Ci at night. But he is still tired because his laziness is so great that he only wants to sleep until Ci pushes a nettle between his legs. And after 6 months, Ci has a son. It could have gone on forever, but one night the black snake comes, sucks on Ci's left breast, sucks it empty, and when the little son comes to suckle on the empty breast, he sucks the snake venom and dies. Then Ci Macunaíma gives a Muiraquitã , a fabulous lucky stone, and rises to a liana up into the sky, where it to the star Beta Centauri , is out of the grave of the young son but the growing Guarana -Pflanze.

During the fight against the Capei , a large water snake, Macunaíma loses the amulet, his only memento of the beloved Ci, and becomes completely sad about it, until the bird Uirapuru tells him that the lost Muiraquitã has been found and is now in his possession Venceslaw Pietro Pietra, a Peruvian trader. The lucky stone made him rich and he now lives in São Paulo . Then Macunaíma and his brothers decide to get the Muiraquitã back. When Macunaíma takes a bath on the way, his dark skin is washed off. The pool in which he bathes is namely the footprint of a giant foot of Sumé , a cultural hero of the Tupí , which he left behind when he brought the Gospel to America. The water in the basin had retained its baptismal effect and still makes you white, blond and blue-eyed.

You continue down the river into the Rio Tietê and finally come to São Paulo, where everything is full of machines. After looking around the city, Macunaíma is ready to visit Venceslaw Pietro Pietra, who is actually the giant Piaimã, an ogre . But that's not a good idea, because the giant notices Macunaíma sitting in a tree, shoots him with an arrow, and drags him into his wine cellar, where he chops up the corpse in order to cook and eat it. Meanwhile, he and his companion, an old, pipe-smoking caipora , drink lots of Chianti . That could have turned out badly had it not been for his brother Maanape, who is knowledgeable about magic, and who had not brought the body parts and resuscitated Macunaíma.

Since the giant now knows Macunaíma, he has to make himself unrecognizable. With the help of some beauty machines, Macunaíma turns into a French woman and arranges a business appointment with the giant. But that doesn't help, because the giant doesn't want to sell or lend the Muiraquitã, but maybe give them away if the French woman ... Macunaíma is only able to flee into an anthill, where he is besieged by Piaimã and can only escape with the loss of all beauty machinery.

Macunaíma is so upset about the renewed failure that he decides to beat up the giant. But since he doesn't feel strong enough to do so himself, he goes to a Macumba ceremony. When the devil Exu has taken possession of a fat old woman, Macunaíma asks him to beat up the giant. Exú then causes the giant's ego to drive into the woman's body, whereupon Macunaíma can calmly beat the woman and every punch and kick he gives the woman benefits the giant.

After that, Macunaíma is hungry and tired. He lands on an island under a tree with a vulture sitting on it, shitting on his head. He asks the morning star and the moon to take it with them, but it stinks too much for both of them. Then Wei , the sun, comes by and takes him away because it needs a son-in-law. She takes him to Rio de Janeiro , where he is supposed to behave. But he does it on the raft of the sun with a fish woman, whereupon nothing comes of the marriage with a sun daughter. He would have become immortal, but what's the point? Here he speaks the key phrase:

"Pouca Saúde e Muita Saúva / Os Males do Brasil São"

"Little health and a lot of ants / is the problem in Brazil!"

The next chapter IX is a letter from Macunaíma to his subjects, the Amazons. In terms of linguistic and stylistic terms, it deviates significantly from the rest of the text, as it uses a parodistically elevated Portuguese mixed with educational chunks, which is mixed with classic educational chunks:

"We have also [...] acquired the Petit Larousse dictionary and are already able to quote many famous sayings of the philosophers and the testicles [sic!] Of the Bible in the Latin original ."

He reports on his so far unsuccessful but laborious attempts to regain the Muiraquitã and his diverse experiences in the big city of São Paulo: that coffee beans are hardly worth anything, colorful pieces of paper all the more so because there are a lot of French women who are mostly not French and are only willing to play for a piece of paper, etc.

The giant has now disappeared from view for some time, as he is recovering from his beating on a trip to Europe and Macunaíma cannot follow him because he has been cheated of his money. In general, he has much to suffer from the injustice and malice of humans and birds, once he even dies from it, but is revived by Maanape, who is known to be a great magician.

Finally the giant is back from Europe and Macuníma feels strong enough to take on him. When the giant arrives, he politely drags Macunaíma into his house and wants to put him on a swing. The swing is made of a thorny liana, but under the swing there is a pot of boiling macaroni, and whoever lets go of the swing falls into the macaroni. So Macunaíma should swing, but he is lazy and he cannot swing and the giant should show him. After some back and forth, the giant gets on the swing and Macunaíma pushes him so hard that he falls into the pot and is cooked over to sauce. His last words are: "Cheese is missing!"

After taking back the Muiraquitã, Macunaíma returns very satisfied to his home on the banks of the Uraricoera. But although the lucky stone is back, resentment and hatred are rampant. Iriqui becomes jealous, flies into the sky with six macaws and becomes the seven stars . Macunaimá is jealous of Jiguê and hates him with leprosy , so that everything rots away and only his shadow remains, for which Jiguês shadow Macunaíma infects with leprosy. Macunaíma again infects all ant species with leprosy. After infecting seven others, Macunaíma gets well again. This annoys the shadow, which begins to devour everything that gets in its way. He also devours his brother Maanape and everything that Macunaíma wants to eat is devoured by the shadow, but he cannot devour Macunaíma because it flees from the shadow, which finally jumps on the shoulder of the vulture father Ruxama and becomes his second head, since then the double-headed.

So Macunaíma is now all alone, the hut has also collapsed, he hangs around in the hammock, eats cashew nuts and lets a young macaw perform the exploits of his youth for him. One day he wakes up from his swamp fever dreams and wants to take a bath in the lagoon, because the sun is hot and he is hot. In the lagoon he sees a beautiful naked woman in the water, but doesn't notice that she has a breathing hole in her neck, namely a Uiara , an immortal ogre living in the water. Macunaíma rises into the water and only comes out with great difficulty. When he is back on the bank, he looks to see what has been eaten away from him: right leg, testicles, nose and ears and lips. But the muiraquita hung from his pierced lips. He poisoned and gutted all the fish in the lagoon, but could not find the muiraquitã. Then he loses his interest in the world and decides to go to heaven. He is planting an air liana. While it grows into the sky (similar to the beanstalk in the fairy tale of Hans and the Beanstalk ), Macunaíma writes on his tombstone:

"I wasn't born to be stone."

Then he climbs up to heaven, where he is first mistaken for Saci , the one-legged goblin, because of the missing right leg . There is no longer any free space in the zodiac either, but eventually it becomes a constellation after all , namely the Great Bear .

And then comes the conclusion: That all of this was past and forgotten, until one day a macaw (the same one who had once learned the deeds of Macunaíma by heart) flew onto the author's shoulder and told him all the stories one after the other.

background

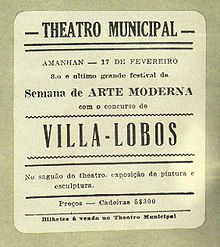

It is a novel that has to be understood against the background of Brazilian modernism , a movement that consciously wanted to oppose European tradition with something of its own, whereby European art of the time was still determined by symbolism and that of Parnassia . The main exponents of Brazilian modernism were Mário de Andrade and the unrelated Oswald de Andrade .

Andrade found the peculiarity of Brazil in the figures of Brazilian mythology, in particular the myths of the Tupi and the Guarani of the Amazon region . Andrade obtained information about these figures, the curupiras , uiaras and others, and above all about the muiraquitãs, the lucky stones made of nephrite that the Icamiabas gave to their lovers from a multi-volume work by the German ethnologist Theodor Koch-Grünberg .

But over this mythological population of his text, which he alternately calls novel, poetry, romance or rhapsody , Andrade does not lose sight of the goal of creating a valid representation of the Brazilian character:

“What interested me in Macunaíma was discovering the national unity of the Brazilians. After a long struggle, one thing seemed certain to me: the Brazilian has no character. By the word character I mean not just an ethical reality, but the enduring psychic essence that expresses itself in everyone, in customs, in external behavior, in language, in history, in the course, for good as well as bad. ... [The Brazilian] is like a twenty year old; it is true that one can perceive general tendencies in it, but nothing specific. Our lack of ethical character stems from this lack of psychological character ... And above all an impromptu existence. "

Another topic, if not the main one, is the languages of Brazil. Namely, on the one hand, the written language Portuguese, which dominated literature at the time, and on the other hand, the spoken Brazilian, enriched with expressions from the Indian languages. On the one hand, this is parodied in the letter to the Amazons in Chapter IX, which was written in a splayed pseudo-educational language; on the other hand, the entire novel is an example of the kind of language that Andrade intended to oppose to the literary language of his time. The fact that he saw this Portuguese as a foreign language to be learned is also expressly discussed several times.

He wanted to free himself from the cultural influence of Europe and lets Macunaíma say:

“I'm not going to Europe, no. I am American and my place is in America. European civilization definitely messes up the unity of our character. "

text

The first version was written within a week of December 1926, followed by three versions over the course of several months. The novel appeared in 1928, initially self-published by the poet. Since then the work has seen numerous editions, several dramatizations and a film adaptation in 1969 under the direction of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade .

The German translation by Curt Meyer-Clason appeared in 1982. The translation seems strange in some places, as long lists of exotic animals, plants and objects appear in the text without comment. But this corresponds to the intention of Andrades, who expressly notes in a note on Macunaíma :

“[Lists] of place names, names of locations, which often correspond to popular and non-geographical-scientific terminology, of devices, birds, fish, insects, fruits: do not translate, just transport! All the lists in the book are imitations of folklore and created with the poetic intention of creating beautiful sentences, strange, new and occasionally funny sounds. Translating them would be useless, even impossible! "

Elsewhere it is strange when, for example, Jiguê's companion missed market time while playing with Macunaíma and therefore couldn't buy cassava for dinner: “So Susi secretly went to the back of the house, sat on her rush basket and pulled one out of her Maissó Heap of cassava roots. ”Maanape doesn't like to eat these cassava roots, and then in the glossary one finds that Maissó is of course the vagina (from Tupí mahussó ).

expenditure

- First edition: Eugenio Cupolo, São Paulo 1928

- Macunaíma. O herói sem nenhum caráter. Critical edition by Telê Porto Ancona Lopez. Illustrations by Petro Nava. LCT, Rio de Janeiro 1978

- Translation: Macunaíma - the hero without any character. Translation and glossary by Curt Meyer-Clason . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-518-02053-6 . New edition: Suhrkamp TB 3198, ISBN 3-518-39698-6

- Filming: Macunaíma

literature

- Theodor Koch-Grünberg : From Roroíma to Orinoco: Results of a trip to northern Brazil and Venezuela in the years 1911-1913. 5 Vols. Reimer, Berlin 1917 (Vol. 3–4 in Strecker and Schröder, Stuttgart)

- Renata R. Mautner Wasserman: Pregüiça and Power: Mário de Andrade's “Macunaíma”. In: Luso-Brazilian Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Summer 1984), pp. 99-116

- Hubert Pöppel: A Strange Brazilian Anti-Gospel: Mário de Andrades Macunaíma. In: Iberoromania . Vol. 56, Issue 2, pp. 148-160

- Lúcia Sá: Rain forest literatures: Amazonian texts and Latin American culture. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2004, pp. 35-68 digitized

Individual evidence

- ↑ Boiuna . Macunaíma cuts off her head, which rises into the sky and becomes the moon.

- ↑ Macunaíma. Suhrkamp TB, p. 34

- ↑ Macunaíma. Suhrkamp TB, p. 65, original p. 169

- ↑ Macunaíma. Suhrkamp TB, p. 78

- ↑ Macunaíma . Epilogue. Suhrkamp TB, p. 171f

- ^ E.g. Macunaíma . Suhrkamp TB, pp. 80f, 92f

- ↑ Macunaíma . Epilogue. Suhrkamp TB, p. 107

- ↑ Macunaíma . Glossary. Suhrkamp TB, p. 163

- ↑ Macunaíma . Suhrkamp TB, p. 114