Maidu

The Maidu are a people of North American Indians from northern California . They settle in the central Sierra Nevada in the catchment area of the Feather River and the American River , as well as in the Humbug Valley . In the language of Maidu ( Maiduan ) means Maidu "man."

classification

The Maidu people are divided into many subgroups due to geographic features (valleys, foothills and mountains in northeastern California). There are three sub-peoples of the Maidu:

- The Nisenan or Southern Maidu occupied the entire American River, Bear River , and Yuba River basins . They live in the areas where the Martis were previously native.

- The northeastern or Mountain Maidu, also known as the Yamani Maidu , lived on the upper reaches of the Feather River, namely on its northern and central headwaters.

- The Konkow ( Koyoom k'awi ) originally came from the Concow Valley between the villages of Cherokee and Pulga along the northern headwaters of the Feather River and its tributaries. The Mechupda (also Chico or Valley Maidu) live in the area of Chico .

Demographics

Estimates of the population of the indigenous peoples of California are highly variable. Alfred L. Kroeber estimated the number of Maidu for 1770 (including the Konkow and Nisenan) at 9,000 people. Sherburne F. Cook slightly increased this assumption to 9,500 people.

Kroeber reported 1,100 maidu in 1910. The 1930 census counted only 93, while the total Maidu population was estimated at 3,500 in 1995.

Culture

The Maidu were hunters and gatherers .

Baskets and basket weaving

They were also exemplary basket weavers who made very decorative and useful baskets, ranging in size from thimble to enormous (several feet in diameter). The stitches on some of these baskets are so finely worked that a magnifying glass is sometimes needed to identify them. In addition to tightly woven, waterproof baskets for cooking, they made large storage baskets, bowls, flat bowls, lids, cradles, hats and mortars. To make the baskets, they used shoots, bark, roots and leaves from dozens of different wild plants. Some of the more common ones were fern roots, the red bark of judas trees, the branches of white willow and the roots of rushes, yucca leaves, and roots of brown marsh grasses and sedges. By combining these different plants, they were able to create geometric designs in red, black, white, dark or light brown. Maidu Elder Marie Potts explains:

“ The coiled and twining systems were both used, and the products were sometimes handsomely decorated according to the inventiveness and skill of the weaver and the materials available, such as feathers of brightly plumaged birds, shells, quills, seeds or beads- almost anything that could be attached.

for example: The braiding and sewing methods were both used. The baskets were sometimes attractively designed, depending on the ingenuity and skill of the braider and the materials available to him, e.g. B. feathers from brightly colored birds, shells, quills or glass beads - almost everything could be incorporated. "

Way of life

Like other California tribes, the Maidu were hunters and gatherers, but not farmers. They practiced a kind Plenterwirtschaft through the use of fire and thus generated groups of oaks to the glans to maximize production. Acorns made their dietary staple , including the eldest Marie Potts performs:

" Preparing acorns as food was a long and tedious process that was undertaken by the women and children. The acorns had to be shelled, cleaned and then ground into meal. This was done by pounding them with a pestle on a hard surface, generally a hollowed-out stone. The tannic acid in the acorns was leached out by spreading the meal smoothly on a bed of pine needles laid over sand. Cedar or fir boughs were placed across the meal and warm water was poured all over, a process which took several hours, with the boughs distributing the water evenly and flavoring the meal.

For example: The preparation of acorns for food was a lengthy and arduous process carried out by women and children. The acorns had to be peeled, cleaned and ground into flour. This was done with the help of a pestle on a hard surface - usually a hollowed out stone. The tannins contained in the acorns were washed out by carefully spreading the flour on a bed of pine needles, which in turn were laid over sand. Cedar or spruce branches were stuck into the flour and warm water was poured over everything, a process that took many hours. The twigs flavored the flour. "

The high availability of acorns made it possible to store large quantities for difficult times. To do this, they used their basket weaving skills and constructed above-ground storage facilities .

In addition to acorns, which provided starch and fats , the Maidu had other resources at their disposal in an environment that was rich in - partly edible - plants and animals. They supplemented their acorn diet with edible roots (for which they were called digging Indians by European immigrants ), fish from the numerous rivers and other plants and animals. Both the seeds of the many flowering plants and the bulbs and roots of many wild flowers provided the subsistence for the population of these areas. Wild plants and animals of all kinds were also included in their spiritual world. Deer, elk and antelopes as well as the variety of smaller animals were regularly hunted. Fish was a primary source of protein, starting with migratory salmon and knowing that local indigenous fish would provide food year round.

Accommodations

Most of the Maidu's residential buildings, especially those in the higher elevations of the hills and mountains, were semi-underground. These houses consisted of handsome circular structures 3.5-5.5 m (12-18 ft) in diameter with floors about one meter (3 ft) below the surface of the earth. After the soil had been excavated, a framework of poles was erected on which slabs of pine bark were placed; A heavy layer of earth at the base of this construction formed the end. A fire on the ground in the center of the hut in a stone-lined pit and a stone mortar were used to prepare food and were always ready to feed the family. A different construction was used for the summer accommodation: cut branches were tied together and attached to young trees and covered with brushwood and droppings. The summer huts were always built with the opening to the east in order to take advantage of the warmth of the rising sun and avoid the afternoon heat.

Social organization

Maidu lived together in clans in smaller villages without any centralized political organization. The leaders were usually chosen from among the crowd of men who led the local Kuksu cult , although they did not exercise permanent authority and were primarily responsible for resolving internal disputes and negotiating all matters that could be settled between villages had to.

religion

The primary religious tradition of the Maidu revolved around the Kuksu cult, which was a religious cult system in central California and was based on a patriarchal secret society characterized by Kuksu or Big Head dances. Maidu Elder Marie Potts expressed that the Maidu are monotheistic people:

“ They greeted the sunrise with a prayer of thankfulness; at noon they stopped for meditation; and at sun set they communed with Kadyapam and gave thanks for blessings throughout the day.

for example: They greeted the sunrise with a prayer of gratitude; at noon they interrupted their activities for meditation; and at sunset they communicated with Kadyapam and thanked for the protection during the day. "

A traditional act for the Maidu was the Bear Dance , with which the Maidu paid homage to the bears in spring. The hibernation of the bears and the survival of winter symbolized perseverance for the Maidu, which was spiritually identified with the animals.

In addition to the Maidu, the Pomo and the Patwin ( belonging to the Wintun ) also followed this cultic system . Later missionaries urged them to change their religion.

languages

The Maidu spoke a language that some authors assigned to the Penuti languages . Although all Maidu spoke one of these languages, their grammar, syntax, and vocabulary were sufficiently different that Maidu - separated by great distances or geographical features - were deterred from traveling due to the almost incomprehensible dialects.

There were four fundamentally distinct branches of the language: Northeastern or Yamonee Maidu (known simply as Maidu ); Southern Maidu or Nisenan ; Northwest Maidu or Konkow ; Valley Maidu or Chico .

Rock art

The Maidu inhabited areas in the northeastern Sierra Nevada. This area and the places they inhabited contain many examples of rock art and petroglyphs . It is unclear whether these rock art originate from the Maidu themselves or their predecessors. Regardless of this, the Maidu incorporated this work into their cultural system, true to their belief that the artifacts are real life energy and thus an integral part of their world.

Tribes

Recognized by federal law

- Berry Creek Rancheria of Maidu Indians

- Enterprise Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Greenville Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria

- Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians , Shingle Springs Rancheria (Verona Tract)

- Susanville Indian Rancheria

- United Auburn Indian Community of the Auburn Rancheria

Not recognized by federal law

- Honey Lake Maidu Tribe

- KonKow Valley Band of Maidu Indians

- Nevada City Rancheria

- Strawberry Valley Band of Pakan'yani Maidu (also known as Strawberry Valley Rancheria )

- Tsi Akim Maidu Tribe of Taylorsville Rancheria

- United Maidu Nation

- Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe of the Colfax Rancheria

- Nisenan

Contemporary artist

- Dalbert Castro - Nisenan

- Frank Day (Ly-dam-lilly) - Konkow

- Harry Eugene Fonseca - Nisenan

- Judith Lowry - Mountain Maidu

- Frank Tuttle - Konkow

- Janice Gould - Konkow

- Wallace Clark - Koyom'kawi yepom (traditional art)

- Jacob A. Meders - Mechoopda-Konkow

Traditional stories

The tales of K'odojapem / World-maker and Wepam / Trickster Coyote are particularly prominent traditional tales of the Maidu .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Michael G. Johnson: Encyclopedia of Native Tribes of North America . Firefly Books, Buffalo, New York 2014, ISBN 978-1-77085-461-1 , p. 198.

- ↑ John Robbins: ACTION: Native American human remains and associated funerary objects: . thefederalregister.com. December 14, 2000. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved on August 14, 2008.

- ↑ Kroeber (1925: 883)

- ^ Cook (1976: 179)

- ^ A b c d Marie Potts: The Northern Maidu . Naturegraph Publishers Inc., Happy Camp, California 1977, ISBN 0879610719 , pp. 34-35.

- ↑ Strawberry Valley Rancheria

- ↑ Frank Tuttle (Konkow Maidu, Yuki, Wailaki)

- ↑ Maidu Indian Legends. Native Languages of the Americas. . Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- ^ William Shipley: The Maidu Indian Myths and Stories of Hánc'ibyjim . (w / forward by Gary Snyder). 1991.

swell

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization . University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kroeber, AL 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California . Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, DC

- Heizer, Robert F. 1966. Languages, Territories, and Names of California Indian Tribes . University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Pritzker, Barry. 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples . Oxford University Press, New York.

Web links

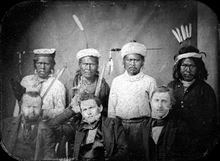

- Maidu Headmen with Treaty Commissioners , July / August 1851