Batavia massacre

Coordinates: 6 ° 8 ′ S , 106 ° 48 ′ E

| date | October 9 to October 22, 1740 |

|---|---|

| place | Batavia , Dutch East Indies |

| Casus Belli | Oppression of the Chinese minority and economic problems |

| output | sustainable alienation of the population groups |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Dutch troops |

Chinese population of Batavia |

| losses | |

|

around 500 dead Dutch soldiers, |

over 10,000 dead |

The massacre of Batavia ( Dutch Chinezenmoord , Chinese murder , Indonesian Geger Pacinan , unrest in the Chinese quarter ) was a pogrom against the ethnic Chinese population in the port city of Batavia (now Jakarta ) in the Dutch East Indies . It extended within the city from October 9th to October 22nd, 1740, while in the surrounding area there were minor riots until well into November. Historians estimate that at least 10,000 Chinese perished in the pogrom and only between 600 and 3,000 of the large Chinese community of Batavia survived.

Since September 1740 there was unrest within the Chinese population, who felt oppressed by the colonial administration and suffered economically from a falling sugar price. In the face of this unrest, Governor General Adriaan Valckenier declared that any uprising would be answered with deadly force. On October 7th, Dutch troops marched into the Chinese quarters to confiscate all weapons and to impose a curfew on the districts. There were clashes with several hundred Chinese and the deaths of 50 soldiers. Two days later, rumors of Chinese atrocities led other populations of Batavia's population to attack Chinese homes, burning many of them along the Besar River. Dutch soldiers also started bombarding the Chinatown with cannons. The violence quickly spread across all of Batavia. Although Valckenier pronounced a general amnesty for all violent crimes committed so far on October 11, this lasted within the city until October 22, when the governor general ordered the violent suppression of all unrest by his own troops. Outside the city, violent conflicts continued between Dutch soldiers and workers at Chinese sugar factories, which reached a final climax after a few weeks when soldiers attacked pockets of resistance in China.

In the following year, the attacks on the Chinese, which spread across Java, triggered a two-year war in which ethnic Chinese and Javanese fought against the Dutch colonial power and sections of the population allied with them. Valckenier was ordered back to the Netherlands in the aftermath of the massacre, where he was tried for crimes related to the riot. The events were clearly reflected in Dutch literature and could etymologically form the basis for the names of some of the districts of today's Jakarta.

background

In the early days of the Dutch colonization of the Malay Archipelago , many Chinese craftsmen were hired to build the city of Batavia, today's Jakarta , on the northwest coast of Java . In addition, many other Chinese settled in the area, working as local and national traders or in the sugar factories. The use of Batavia as a stopover for trade between the Dutch East Indies and China resulted in an economic upswing there, which encouraged the settlement of more Chinese on Java. Their number in Batavia grew steadily and reached 10,000 around 1740. Several thousand also lived outside the city. The Dutch colonial authorities forced the Chinese to carry national passports with them and sent back to China those that could not be shown at controls.

Control and deportation policies were tightened in the 1730s after several thousand people, including Governor General Dirck van Cloon , perished in a malaria outbreak . According to the Indonesian historian Benny G. Setiono, the outbreak of the epidemic was followed by increased distrust and rumors of the indigenous Indonesians and the Dutch against the growing Chinese minority, which was economically very successful. As a further measure of repression born out of this distrust, the Commissioner for Native Affairs Roy Ferdinand, on behalf of Governor General Valckenier, passed a decree on July 25, 1740, according to which suspicious elements of the Chinese population were to be deported to Zeylon (today's Sri Lanka ) and to grow cinnamon there. Wealthy Chinese were ransomed by corrupt officials under threat of deportation. Thomas Stamford Raffles , a British explorer and expert on the history of Java, noted in 1830 that it was common among the Javanese that the Dutch administration had agreed with the Chinese leader they had appointed during the deportations . The latter asked them to deport Chinese people who wore black or blue, as this was a sign of poverty. There were also rumors that the deportees would not be brought to their destinations, but would be thrown overboard out of sight from the coast. According to other rumors, many died in riots they sparked on the ships. The deportations created general dissatisfaction among the Chinese and many workers stopped showing up at their workplaces.

At the same time as these events, the indigenous people of Batavia such as the Betawi , who were often slaves and servants, became increasingly suspicious of the Chinese. Economic reasons played an important role here. While many natives were poor, the Chinese were considered rich. They were accused of only living in the richest neighborhoods. The Dutch historian AN Paasman referred to the Chinese of that time as the "Jews of Asia", but the situation was much more complex. Many of the poorer Chinese worked in the sugar factories and felt exploited by both the Dutch colonizers and richer Chinese. The latter owned many of the factories and controlled the agriculture and the transportation of goods. They made huge profits with the sugar they produced and an alcoholic drink based on this and rice called arrak . The actual sugar price was set by the Dutch colonial administration, which has always led to unrest. Although the export of sugar to Europe increased from the 1720s, increasing competition from the West Indies put pressure on the price. The sugar industry in East India suffered significantly from the fall in prices. In 1740 the world price for sugar had fallen to half its value in 1720, which brought the colony, whose main export good was sugar, into considerable economic difficulties.

The Raad van Indië (India Council) initially assumed that there would be no attack by dissatisfied Chinese on Dutch rule. For this reason, a faction led by Gustaaf Willem van Imhoff , which was in opposition to Governor General Valckenier, blocked the tightening of measures against the Chinese. Van Imhoff, who had previously lived in Batavia, had meanwhile been governor of Zeylon and had been back in the city since 1738. In September 1740, a large number of disaffected Chinese from surrounding settlements gathered at the gates of Batavia. To this end, Valckenier convened an emergency council meeting on September 26, during which he ordered the use of deadly force against any attempted Chinese insurgency. This order provoked sharp protests from the ranks of the opposition around Van Imhoff. Johannes Vermeulen suspects that the conflict between the two ethnic groups perceived as colonizers had a major influence on the massacre that soon followed.

On the evening of October 1, Valckenier was reported that a crowd of about a thousand Chinese had gathered at the gates five days earlier as a result of his testimony at the emergency meeting. Valckenier and the Council initially reacted in disbelief to this report. After reports that a Balinese sergeant had been killed by the angry crowd, the council decided to take extraordinary measures and strengthen the guards. Two groups of 50 European soldiers and supporting native porters were sent to outposts south and east of the city and a plan of attack was drawn up.

incident

massacre

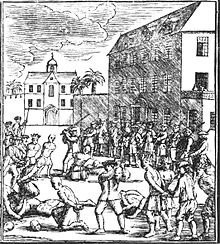

After groups of Chinese factory workers armed with self-made weapons began looting and setting fire to sugar factories, hundreds of ethnic Chinese, supposedly led by Ni Hoe Kong, the captain of Cina, killed 50 Dutch soldiers on October 7 in the Meester Cornelis district (now Jatinegara ) and Tanah Abang . In response, the colonial administration sent 1,800 soldiers, accompanied by Shutteriy militias and eleven battalions of conscripts, on the march to put down the uprising. They announced a curfew and canceled a planned Chinese festival. Because the soldiers feared communication via light signals, they forbade the use of candles and confiscated weapons-grade equipment such as small kitchen knives within the city. The following day, the Dutch troops repelled an attack by up to 10,000 Chinese on the outer city walls. The attackers were led by groups from Tangerang and Bekasi . Raffles writes that 1,789 Chinese died in these fighting. In response to the events, Valckenier convened a new council meeting on October 9th.

Meanwhile, rumors were circulating among the city's other ethnic groups, including slaves from Bali and colonial troops from there and Sulawesi , that a Chinese conspiracy to kill, enslave or rape them was under way. These rumors led to the attack and burning of Chinese houses on the Besar River. This was followed by attacks by Dutch troops on other Chinese neighborhoods, where residents were killed and their houses set on fire. The Dutch politician and critic of colonialism, WR van Hoëvell, writes that pregnant and breastfeeding women and old men were killed and prisoners slaughtered "like sheep".

Soldiers under Lieutenant Hermanus van Suchtelen and Captain Jan van Oosten, a survivor of the events in Tanah Abang, took up positions in the Chinese district. Van Suchtelen kept the poultry market occupied while van Oosten's men watched a nearby canal. From around 5 p.m., the Dutch opened fire from cannons on Chinese houses, which caught fire. Some of the residents burned to death in their homes, while those who tried to leave were shot by soldiers. Others committed suicide in desperation. Some managed to run as far as the canal, where troops waited in small boats and also killed the refugees. Some Dutch people pushed into the alleys between the burning houses and killed every survivor they encountered. The violence later spread across the city. According to Vermeulen, the perpetrators were often sailors and other "unusual and bad elements" of society. There was also extensive looting and arbitrary appropriation of Chinese property.

The following day, the violence continued, with injured Chinese people being dragged from a hospital and killed. Attempts to put out the fires that had broken out the day before failed, causing them to spread and burn until October 12th. At the same time, around 800 Dutch soldiers and 2,000 natives attacked Kampung Gading Melati, where a group of Chinese led by Keh Pandjang had holed up. The latter initially withdrew to Paninggaran, but were later driven out of the area completely. Around 450 Dutch and 800 Chinese died in the fighting.

More violence

On October 11th, Valckenier unsuccessfully urged his officers to call their troops to order and stop the looting. Two days later the council offered a reward of two ducats for every Chinese head given to the troops in order to induce the other ethnic groups to participate in the massacres. This led to a real hunt for Chinese people who had survived the first massacre. The Dutch made extensive use of members of various ethnic groups such as the Bugis and Balinese in their actions . On October 22nd, Valckenier ordered the massacres to stop. In a long letter he wrote that they were fully responsible for the unrest and offered an amnesty to all but the leaders of the uprisings. He put a bounty of 500 Reichstalers on the leaders .

Outside the city, confrontations and fighting between Chinese insurgents and Dutch troops continued. On October 25, after almost two weeks of minor fighting, around 500 armed Chinese attacked Cadouwang (now Angke ). They were repulsed by Dutch cavalry under Rittmeister Christoffel Moll and the cornets Daniel Chits and Pieter Donker. The following day, the cavalry unit, consisting of 1,594 Dutch and local residents, advanced against the now fortified sugar factory of Salapadjang. After gathering in a nearby forest, they set fire to the factory where many Chinese people holed up. Another unit also took action against the sugar factory at Boedjong Renje. Fearing the Dutch, many Chinese withdrew to the factory at Kampung Melayu, about four hours from Salapadjang. After heavy fighting, it was captured by a unit under Captain Jan George Crummel. After retaking the post at Qual, the Dutch withdrew to Batavia. In the meantime a group of Chinese was on the run. The way to the west was blocked by around 3000 soldiers from the Sultanate of Banten , which is why they fled east along the north coast of Java. They should have reached Tangerang by October 30th.

On November 2, an order for an armistice reached Crummel, who thereupon left a crew of 50 men at Cadouwang and withdrew to Batavia. When he got there in the afternoon, there were no more Chinese outside the walls. On November 8, the Sultanate of Cirebon sent between 2,000 and 3,000 soldiers to reinforce the city's garrison. The looting lasted until November 28th, and the last of the native militias broke up by the end of the month.

Follow-up time

Most investigations into the massacre assume that around 10,000 Chinese people have died within Batavia. In addition, at least 500 were seriously injured. Between 600 and 700 Chinese owned houses were looted and burned down. Vermeulen suspects 600 survivors, while the Indonesian scientist ART Kemasang assumes 3,000. The Indonesian historian Benny G. Setiono states that around 500 prisoners and the wounded in hospitals were killed and a total of 3,431 Chinese survived. The massacre subsequently led to further pogroms across the whole of Java, for example in Semarang in 1741 and later in Surabaya and Gresik .

Part of the conditions under which the massacre ended was the relocation of all of Batavia's ethnic Chinese to a so-called pecinan , a special Chinese quarter outside the city walls. This is known today under the name Glodok . The concentration of the Chinese in such a closed area made it easier for the authorities to monitor them. However, the first Chinese had already returned to the city itself in 1743. Several hundred traders operated there. Other Chinese fled to Central Java under Khe Pandjang and attacked Dutch guards there. They were later joined by troops under the command of the Sultan of Mataram , Pakubuwono II . While another uprising was suppressed in 1743, there were regular confrontations all over Java for the next 17 years or more.

On December 6, 1740, van Imhoff and two other council members were arrested on Valckenier's orders for disobedience and on January 13, 1741, they were sent to the Netherlands on various ships. They arrived there on September 19th that year. In the Netherlands, van Imhoff convinced the government council that Valckenier was responsible for the massacre. In a long speech called “Consideratiën over den Tegenwoordigen Staat van de Ned. OI Comp. ”(Reflections on the current state of the Dutch East India Company) he was able to dispel doubts about his presentation on November 24th. As a result of his persuasion, the charges against van Imhoff and the other Batavias councilors were dropped. On October 27, 1742, van Imhoff was sent back to Batavia as the new Governor General of the Dutch East Indies on board the ship manufacturer . The leadership of the Dutch East India Company had high hopes for the new governor. He arrived at his new official residence on May 26, 1743.

Valckenier had already asked to be dismissed from his post at the end of 1740. In February 1741 he received an answer according to which he should appoint van Imhoff as his successor. In another account of the events surrounding his replacement, he was fired from the leadership of the East India Company because he exported too much sugar and too little coffee in 1739 and thus caused financial losses. At the time when the reply to Valckenier arrived, van Imhoff was already on his way back to Europe. Valckenier left the Dutch East Indies on November 6, 1741, after having appointed Johannes Thedens as his interim successor. He took command of a fleet sailing to the Netherlands. On January 25, 1742 he arrived in Cape Town , where he was imprisoned by the local governor Hendrik Swellengrebel on the orders of the East India Company. In August he was sent back to Batavia and imprisoned in the fort there. Three months later, he was charged, among other things, for his role in the 1740 massacre. In March 1744 he was found guilty and sentenced to death and all his property was confiscated. In December, the process was resumed with a lengthy statement by Valckenier. Vermeulen classifies the procedure as unfair and influenced by public outrage in the Netherlands. Vermeulen's argument is reinforced by a compensation payment of 725,000 guilders, which Valckenier's son Adriaan Isaäk Valckenier received in 1760.

Sugar production in the region suffered significantly from the massacre as it was largely Chinese owned and many of the owners and workers were either dead or disappeared. She received new impulses from the "colonization" of Tangerang by van Imhoff. He wooed settlers in the Netherlands to cultivate the land and portrayed those who had previously settled there as lazy. High taxes deterred many from immigrating, which is why van Imhoff finally sold the land to Dutch people who were already living in Batavia. As he expected, most of them did not want to cultivate the land themselves, but leased it to ethnic Chinese. Production then increased again, but did not reach the values of before 1740 until the 1760s before it collapsed again. The number of sugar factories had also decreased as a result of the massacre, from 131 in 1710 to 66 in 1750.

Effects

Vermeulen writes that the massacre was one of the most decisive events in Dutch colonialism in the 18th century. In his dissertation, WW Dharmowijono points out that the massacre had a significant impact on Dutch literature. As an early example, he cites a poem by Willem van Haren from 1742, which condemns the pogrom. Another poem from the period by an anonymous author criticizes the Chinese. Raffles described the processing of events in Dutch historiography in 1830 as "far from being complete or satisfactory".

The Dutch historian Leonard Blussé blames the massacre indirectly for the rapid growth of Batavia. In addition, it had institutionalized a modus vivendi that created a split between the Chinese and other ethnic groups that continued into the late 20th century. The names of several neighborhoods in modern Jakarta could be related to the events. One possible such name is the Tanah Abang district , which means red earth and could allude to the blood shed there. Van Hoëvell sees this name as a compromise to persuade the surviving Chinese to accept the granted amnesty. The name Rawa Bangke in eastern Jakarta could come from an Indonesian word with vulgar connotations for corpse, bangkai . This is attributed to the large number of Chinese killed there. A similar etymological source is suggested for Angke in Tambora sub- district.

Remarks

- ^ Mely G. Tan: Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia. 2005, p. 796.

- ↑ a b Merle Calvin Ricklefs: A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200. 2001, p. 121.

- ^ A b c d M. Jocelyn Armstrong, R. Warwick Armstrong and Kent Mulliner: Chinese Populations in Contemporary Southeast Asian Societies. Identities, Interdependence, and International Influence. 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ a b c W. W. Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 297.

- ↑ a b c d e f Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran politics. 2008, pp. 111-113.

- ↑ a b c d e f W. W. Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 298.

- ↑ a b A. N. Paasman: Een klein aardrijkje op zichzelf, de multiculturele samenleving en de etnic literatuur. 1999, pp. 325-326.

- ^ A b Daniel George Edward Hall: A History of South-East Asia. 1981, p. 357.

- ^ A b c d Lynn Pan: Sons of the Yellow Emperor. A History of the Chinese Diaspora. 1994, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ a b W. W. Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 302.

- ^ A b Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 1830, p. 234.

- ^ Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 1830, pp. 233-235.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 461-462.

- ^ A b c Ann Kumar: Java and Modern Europe. Ambiguous encounters. 1997, p. 32.

- ^ A b Christine E. Dobbin: Asian Entrepreneurial Minorities. Conjoint Communities in the Making of the World Economy 1570–1940. 1996, pp. 53-55.

- ↑ Sucheta Mazumdar: Sugar and Society in China. Peasants, Technology, and the World Market. 1998, p. 89.

- ↑ Katy Ward: Networks of Empire. Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company. 2009, p. 98.

- ^ A b c Atsushi Ota: Changes of Regime and Social Dynamics in West Java. Society, State, and the outer world of Banten, 1750-1830. 2006, p. 133.

- ^ August von Wachtel: Development of the Sugar Industry. 1911, p. 200.

- ↑ WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, pp. 297-298.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 460.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Gustaaf Willem, baron van Imhoff. 2011.

- ^ Johannes Theodorus Vermeulen: De Chineezen te Batavia en de troebelen van 1740. Proefschrift, Leiden 1938.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 465-466.

- ↑ a b W. R. van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp 466-467.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 268.

- ↑ For example, the Qual post on the Tangerang River, occupied by 15 Dutch soldiers, was surrounded by at least 500 Chinese. Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 473.

- ↑ Ni has demonstrably survived both these attacks and the subsequent massacre. How he managed this has not been conclusively clarified. It is speculated that he was hiding in a secret basement under his house or dressed as a woman in the governor's palace. WR van Hoëvell suspects that he later fled from it and hid with several hundred people in a Portuguese church near the Chinese quarters. He was later arrested and charged with leading the riot. But even under torture he did not admit this. WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, pp. 302-303; Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 585.

- ↑ Lynn Pan: Sons of the Yellow Emperor. A History of the Chinese Diaspora. 1994, p. 36.

- ↑ a b Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, p. 114.

- ^ A b c Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 1830, p. 235.

- ↑ Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, pp. 114-116.

- ↑ ... Zwangere vrouwen, zoogende moeders, argelooze kinderen, bevende grijsaards been door het zwaard geveld. Den weerloozen was given as schapen de keel afgesneden Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 485.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 486.

- ^ A b c Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran politics. 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 485.

- ↑ vele ongeregelde en bad elements WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 299.

- ↑ WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 299.

- ^ A b c Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran politics. 2008, pp. 118-119.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 489-491.

- ↑ Other spellings of his name are Que Pandjang, Si Pandjang or Sie Pan Djiang. Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 1830, p. 235; WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 301; Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran politics. 2008, p. 135. According to Setiono, his real name may have been Oie Panko.

- ↑ a b c d W. W. Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 300.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 493-496.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 503-506.

- ↑ a b W. R. van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp 506-507.

- ↑ Merle Calvin Ricklefs: The crisis of 1740-1 in Java. The Javanese, Chinese, Madurese and Dutch, and the Fall of the Court of Kartasura. 1983, p. 270.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 506-508.

- ↑ a b Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, p. 119.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, pp. 491-492.

- ↑ ART Kemasang: The 1740 Massacre of Chinese in Java. Curtain Raiser for the Dutch Plantation Economy. 1982, p. 68.

- ↑ Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, p. 121.

- ↑ ART Kemasang: Overseas Chinese in Java and Their Liquidation in 1740. 1981, p. 137.

- ↑ Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, pp. 120-121.

- ↑ WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 301.

- ↑ Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, pp. 135-137.

- ^ Pieter Geyl: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Stam. 1962, p. 339.

- ^ Rutger van Eck: "Luctor et emergo", of, de Geschiedenis der Nederlands in the East-Indian Archipelago. 1899, p. 160.

- ↑ a b Petrus Johannes Christiaan Blok and Philip Molhuysen (ed.): Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. 1927, pp. 632-633.

- ↑ Alexander JP Raat: The Life of Governor Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789). A Personal History of a Dutch Virtuoso. 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Rutger van Eck: "Luctor et emergo", of, de Geschiedenis der Nederlands in the East-Indian Archipelago. 1899, p. 161.

- ^ A b Pieter Geyl: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Stam. 1962, p. 341.

- ↑ Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, pp. 125-126.

- ↑ Ewald Vanvugt: Wettig opium. 350 jaar Nederlandse opiumhandel in de Indian archipelago. 1985, p. 106.

- ↑ Merle Calvin Ricklefs: A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200. 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Alexander JP Raat: The Life of Governor Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789). A Personal History of a Dutch Virtuoso. 2010, p. 82.

- ^ AW Stellwagen: Valckenier en Van Imhoff. 1895, p. 227.

- ↑ Petrus Johannes Blok and Philip Christiaan Molhuysen (eds.): Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. 1927, pp. 1220-1221.

- ↑ Ewald Vanvugt: Wettig opium. 350 jaar Nederlandse opiumhandel in de Indian archipelago. 1985, pp. 92-95 and 106-107.

- ↑ Petrus Johannes Blok and Philip Christiaan Molhuysen (eds.): Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. 1927, p. 1220.

- ^ H. Terpstra: Rev. of Th. Vermeulen, "De Chinezenmoord van 1740". 1939, p. 246.

- ↑ Petrus Johannes Blok and Philip Christiaan Molhuysen (eds.): Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. 1927, p. 1221.

- ^ David Bulbeck, Anthony Reid, Lay Cheng Tan, and Yiqi Wu: Southeast Asian Exports since 14th century. Cloves, Pepper, Coffee, and Sugar. 1998, p. 113.

- ↑ "... striking feiten uit onze 18e-eeuwse colonial divorced is dead onderwerp taken"

- ^ H. Terpstra: Rev. of Th. Vermeulen, "De Chinezenmoord van 1740". 1939, p. 245.

- ↑ WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. 2009, p. 304.

- ^ Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 1830, p. 231.

- ↑ Leonard Blussè: Batavia, 1619-1740. The Rise and Fall of a Chinese Colonial Town. 1981, p. 96.

- ↑ a b Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran policy. 2008, p. 115.

- ^ Wolter Robert van Hoëvell: Batavia in 1740. 1840, p. 510.

literature

- M. Jocelyn Armstrong, R. Warwick Armstrong, and Kent Mulliner: Chinese Populations in Contemporary Southeast Asian Societies. Identities, Interdependence, and International Influence. Curzon, Richmond 2001, ISBN 978-0-7007-1398-1 , OCLC 45484306 .

- Petrus Johannes Blok and Philip Christiaan Molhuysen (eds.): Nieuw Nederlandsch Biografisch Woordenboek. 7th edition, AW Sijthoff, Leiden 1927, OCLC 309920700 . Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Leonard Blussè: Batavia, 1619-1740. The Rise and Fall of a Chinese Colonial Town. In: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Issue 12, Volume 1, 1981, doi : 10.1017 / S0022463400005051 , ISSN 0022-4634 , OCLC 470182526 . Pp. 159-178.

- David Bulbeck, Anthony Reid, Lay Cheng Tan and Yiqi Wu: Southeast Asian Exports since 14th century. Cloves, Pepper, Coffee, and Sugar. KITLV Press, Leiden 1998, ISBN 978-981-3055-67-4 , OCLC 39065400 .

- WW Dharmowijono: Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins. het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880–1950. Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2009. PhD thesis, accessed on 29 August 2013.

- Christine E. Dobbin: Asian Entrepreneurial Minorities. Conjoint Communities in the Making of the World Economy 1570–1940. Curzon, Richmond 1996, ISBN 978-0-7007-0404-0 , OCLC 43411634 .

- Rutger van Eck: "Luctor et emergo", of, de Geschiedenis der Nederlands in the East-Indian Archipelago. Tjeenk Willink, Zwolle 1899, OCLC 67507521 .

- Pieter Geyl: Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Stam. Volume 4, Wereldbibliotheek, Amsterdam 1962, OCLC 769104246 .

- Daniel George Edward Hall: A History of South-East Asia. 4th illustrated edition, Macmillan, London 1981, ISBN 978-0-333-24163-9 , OCLC 7566533 .

- Wolter Robert van Hoëvell : Batavia in 1740. In: Tijdschrift voor Nederlands Indie. Issue 3, Volume 1, 1840. pp. 447-557.

- ART Kemasang: Overseas Chinese in Java and Their Liquidation in 1740. In: Southeast Asian Studies. Issue 19, 1981, OCLC 681919230 . Pp. 123-146.

- ART Kemasang: The 1740 Massacre of Chinese in Java. Curtain Raiser for the Dutch Plantation Economy. In: Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. Issue 14, 1982, ISSN 0007-4810 , OCLC 819294583 . Pp. 61-71.

- Ann Kumar: Java and Modern Europe. Ambiguous encounters. Curzon, Richmond 1997, ISBN 978-0-7007-0433-0 , OCLC 37510526 .

- AN Paasman: Een klein aardrijkje op zichzelf, de multiculturele samenleving en de etnic literatuur. In: Literature. Issue 16, 1999, OCLC 72724011 . Pp. 324-334. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Lynn Pan: Sons of the Yellow Emperor. A History of the Chinese Diaspora. Kodansha Globe, New York 1994, ISBN 978-1-56836-032-4 , OCLC 30155598 .

- Sucheta Mazumdar: Sugar and Society in China. Peasants, Technology, and the World Market ( Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series. Volume 45). Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge 1998, ISBN 978-0-674-85408-6 , OCLC 38281638 .

- Atsushi Ota: Changes of Regime and Social Dynamics in West Java. Society, State, and the outer world of Banten, 1750-1830 ( TANAP Monographs on the History of the Asian-European interaction. Volume 2). Brill, Leiden 2006, ISBN 978-90-04-15091-1 , OCLC 62755670 .

- Alexander JP Raat: The Life of Governor Joan Gideon Loten (1710–1789). A Personal History of a Dutch Virtuoso. Lost, Hilversum 2010, ISBN 978-90-8704-151-9 , OCLC 660216260 .

- Thomas Stamford Raffles: The History of Java. Volume 2. 2nd edition, Black, London 1830, OCLC 312809187 .

- Merle Calvin Ricklefs: The crisis of 1740-1 in Java. The Javanese, Chinese, Madurese and Dutch, and the Fall of the Court of Kartasura. In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- and Folklore. Issue 139, Volume 2/3, 1983, ISSN 0006-2294 , OCLC 2855914 . Pp. 268-290. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- Merle Calvin Ricklefs: A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200. 3rd edition, Stanford University Press, Stanford 2001, ISBN 978-0-8047-4479-9 , OCLC 49030264 .

- Benny G. Setiono: Tionghoa dalam Pusaran politics. Elkasa, Jakarta 2008, ISBN 978-979-96887-4-3 , OCLC 52593566

- AW Stellwagen: Valckenier en Van Imhoff. In: Elsevier's Geïllustreerd Maandschrift. Issue 5, Volume 1, 1895, ISSN 1875-9645 , OCLC 781596392 . Pp. 209-233.

- Mely G. Tan: Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia. In: Melvin Ember, Carol R. Ember and Ian Skoggard (Eds.): Encyclopedia of Diasporas. Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Springer Science + Business Media, New York 2005, ISBN 978-0-387-29904-4 , OCLC 318289944 . Pp. 795-807.

- H. Terpstra: Rev. of Th. Vermeulen, "De Chinezenmoord van 1740". In: Tijdschrift Voor Geschiedenis. 1939, ISSN 0040-7518 , OCLC 7508094 . Pp. 245-247. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Ewald Vanvugt: Wettig opium. 350 jaar Nederlandse opiumhandel in de Indian archipelago. In de Knipscheer, Haarlem 1985, ISBN 978-90-6265-197-9 , OCLC 15125268 .

- August von Wachtel: Development of the Sugar Industry. In: The American Sugar Industry and Beet Sugar Gazette. Issue 13, May, 1911, OCLC 9834572 . Se. 200-203.

- Katy Ward: Networks of Empire. Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company ( Studies in Comparative World History. ). Cambridge University Press, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7 , OCLC 182552865 .

Web links

- Encyclopædia Britannica: Gustaaf Willem, baron van Imhoff. 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2013.