Mayan Toltecs

The Mayan Toltecs are a hypothetical ethnic group who are considered to be the creators of the motifs and representations in Chichén Itzá , reminiscent of models in Tula . The existence of this ethnic group, which is said to be of Toltec origin, is inferred from the similarities in architecture and pictorial representations. It is associated with a mythical hike led by the Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl . There is no direct evidence of their existence or origin.

The result

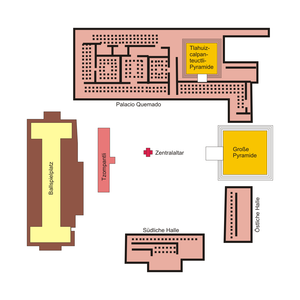

The similarities between representations on structures and building floor plans in Tula and those in Chichén Itzá have been known since the excavations in Tula at the end of the 1930s. They are so clear not only thematically, but also in their execution that it is not unreasonable to assume that the role models in one place must have been known to those who carried out the work in the other. The most important are:

- Columns with carved pillars

- Temple with a large interior supported by pillars on a stepped pyramid, inserted in porticoed halls.

- The Tlahuizcalpanteuctli temple in Tula was reconstructed in the 1950s based on the model of the warrior temple of Chichén Itzá, the resemblance is therefore not entirely real

- Columned halls with an open front, with stone benches along the walls and seating platforms, there a relief of warrior procession, upper edge snake pattern.

- Tzompantli (scaffolding) in the west of the central courtyard

- Large ball court on the western edge of the central courtyard

- Altar platform near the center of the central courtyard with stairs on all four sides

- Relief depicting a bird-man in a characteristic pose

- Reliefs with processions of jaguars

- Reliefs with eagles devouring hearts

- Depictions of warriors with Toltec armament (spear thrower, shield) and costume

Even the spatial arrangement of the corresponding buildings in Tula and Chichén Itzá shows similarities, although the dimensions in Chichén Itzá are considerably larger.

The theories

The dating of the arrival of the Quetzalcoatl kukulkan according to the text sources

The end of Tollan was more than half a millennium ago when the texts were written in the early colonial period. Historical information almost obscured by mythical ideas. According to most of these texts, the end of Tollan is directly related to the exodus or the flight of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. Already the earliest historical report, the double source "Relación de la Genealogía" and "Origen de los Mexicanos", written only eleven years after the conquest of Tenochtitlan by unnamed Franciscan monks on the basis of local traditions, describes in short words that Topiltzin from Tollan and moved to a country called Tlapallan, which the source says local informants did not know where it was. He soon died there. Similarly, it says in all of Bernardino de Sahagún's texts: “... then he arrived at the coast, where he made a raft of snakes. He sat down on it as if it were his boat. Then he drove across the sea. Nobody knows how he got there in Tlapallan ”(quote translated directly from the Náhuatl ). How little the Indian contemporaries knew what to do with the term “Tlapallan”, the Indian author Chimalpahin shows: Quetzalcoatl would have moved from Tollan to the east to the sea, the Gulf of Mexico, “where it is in smoke and red color [ Tlapallan] "(translated directly from the Náhuatl). Traditionally, Tlapallan, also in the form “Tlillan Tlapallan” (both in the form of place names), is understood as the land of black and red, and equated with the land of the Maya (perhaps because the characters of the Maya codices in the colors red and are painted black), although the sources expressly state that the location is not known.

The sources do not agree on the date of the extract of the top interest rate. Chimalpahin names the year 1051 AD, the Anales de Cuauhtitlan , written by unknown Indians in Náhuatl, offer 895 or 883. The first two years in the Aztec calendar correspond to a year 1 acatl , which is also the calendar nickname Topiltzins, so these dates are derived from the name and should not be authentic. The third date is called the Tetzcoco tradition . According to this source, Topiltzin would have burned himself.

Dating played an essential role in interpreting the Toltec influence in the Yucatán . Alfred M. Tozzer arbitrarily moved the dates given by the sources to the year 999 by postponing Topiltzin's excerpt by several calendar laps of 52 years, after which the same Aztec date recurs. Nevertheless, he lets the Toltec influence in Chichén Itzá start earlier, but only sees a "historical Kukulkan" from around 1150 AD. In contrast, John Eric Thompson took the view that the Itzá , in which he was one not the Maya belonging to the population group, who came from the island of Cozumel, settled in Chichén Itzá around 918 AD. This assumption is based on a somewhat confused migration history in the Chilam Balam book by Chumayel , which names a year in Tun 11 Ahau, a designation that, however, recurs every 13 years and is therefore not very precise. They were followed by Thompson Kukulkan (the Mayan equivalent of Quetzalcoatl) in Katun 4 Ahau, i.e. in the period between 967 and 987 AD. He relies on a prophetic statement in the Chilam-Balam text by Chumayel, which he calls interpreted historically, and justified the selection of the absolute time approach (because a katun with the same name occurs every 256 years) with the fact that this would be the first katun of this name after the hieroglyphic inscriptions ceased to exist.

As Nigel Davies explains, the date 987 chosen by Thompson is based on the conversion of the Central Mexican date 1 acatl according to the Mixtec calendar defined by Wigberto Jiménez Moreno , which he hypothetically applied to the events in Tollan. As he emphasizes, Thompson's assumption reinforced this, which is a classic circular argument. Since the date 1 acatl is part of the name of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, any dating based on it is doubtful.

While the authors mentioned took the direction of transmission from Tula to Chichén Itzá as given, George Kubler favored the opposite direction. He emphasizes that nothing in Tula corresponds to the early phases of Toltec art in Chichén Itzá, so that Tula was more of a colonizing outpost of Chichén Itza. For this assumption a very late approach of the sinking of Tula around 1260 is necessary, which for historical as well as archaeological reasons cannot be maintained.

Archaeological dating

The archaeological dating situation for both sites is unsatisfactory. Few radiocarbon dates are available for Tula. Together with the ceramic dating, it is assumed that a city began to emerge around 700 AD, whereby the influence of Teotihuacán is unmistakable. The buildings of the ceremonial center of Tula that are preserved today are dated to the early post-classical period (between 900 and 1200 AD). The end of Tula is marked by deliberate destruction, such as the burning down of the columned halls and the “burial” of the large figure columns in a specially dug in the pyramid.

Chichén Itzá's history begins almost simultaneously around AD 750 and lasted until around the year 1000. The monuments dated range from AD 864 to AD 998, the most recent dates can be found on stone pillars in the temple of the so-called high priest's tomb, the at the same time carry reliefs in the style of the colonnades, i.e. indirectly date them. Radiocarbon dates are between 835 and 900 AD with a large uncertainty factor. There is currently broad consensus that the main construction activity in Chichen Itzá is earlier than that in Tula. In the main dating medium of archeology, ceramics, a foreign element does not appear at all.

The distance problem

The distance between Tula and Chichén Itzá is a good 1400 km, without other archaeological discoveries having been made on this route, which undoubtedly have the same characteristics and could be assigned to a migration or contact route from Toltecs to the northern Yucatán. Attempts to avoid this difficulty are approaches that assign Chichén Itzá like Tula and other places to an "international style" in which a cult of the feathered serpent (Quetzalcoatl) manifested itself.

literature

- Henri Stierlin: The Art of the Maya - from the Olmecs to the Maya-Toltecs. Belser, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-7630-2348-8 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Susan Gillespie: Toltecs, Tula and Chichén Itzá, the development of an archaeological myth In: Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World . Jeff Karl Kowalski / Cynthia Kristan-Graham (Eds.) Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC 2007. pp. 85-128

- ↑ Bernardino de Sahagún: Florentine Codex Vol. 3 Arthur JO Anderson / Charles E. Dibble (eds.). School of American Research, Santa Fe 1952. p. 36

- ↑ Domingo de San Anton Muñon Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin: The Memorial Breve acerca de la fundación de la ciudad de Culhuacan . Walter Lehmann / Gerdt Kutscher (eds.). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1958. p. 11

- ^ Hanns J. Prem : Los reyes de Tollan y Colhuacan . In: Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl Vol. 30, 1999, ISSN 0071-1675 . Pp. 23-70.

- ^ Alfred M. Tozzer: Chichen Itza and its Cenote of Sacrifice . Peabody Museum, Cambridge, MA 1957. p. 30

- ↑ John Eric Thompson : Maya history and religion . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1970. ISBN 0-8061-0884-3 . Pp. 10-11

- ↑ Ralph L. Roys : The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1967. pp. 70-73

- ↑ Ralph L. Roys: The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1967. p. 161

- ↑ Nigel Davies: The toltecs, until the fall of Tula . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1977. ISBN 0-8061-1394-4 . P. 218

- ↑ Wigberto Jiménez Moreno: Sintesis de la historia precolonial del Valle de México . In: Revista Mexicana de Estudios Antropológicos Vol. 14, 1954-55. Pp. 219-236. P. 224

- ^ George Kubler: Chichén Itzá y Tula . In: Estudios de Cultura Maya , Vol. 1, 1961. ISSN 0185-2574 pp. 47–80 ( online ( memento of the original from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; PDF; 6.4 MB)

- ↑ Michael E. Smith: Tula and Chichén Itzá, are we asking the right questions? In: Twin Tollans: Chichén Itzá, Tula, and the Epiclassic to Early Postclassic Mesoamerican World . Jeff Karl Kowalski / Cynthia Kristan-Graham (Eds.) Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC 2007. pp. 579-618

- ↑ Alba Guadalupe Mastache / Robert H. Cobean: Tula . in: The Oxford encyclopedia of Mesoamerican cultures . Oxford University Press, New York 2001. ISBN 0-19-510815-9 . Vol. 3, pp. 269-274

- ↑ Peter J. Schmidt: Los “totecas” de Chichén Itza, Yucatán . In: Arqueología mexicana 86 (2007) pp. 64–68

- ^ William M. Ringle et al .: The return of Quetzalcoatl, evidence for the spread of a world religion during the Epiclassic period . In: Ancient Mesoamerica 9, 1998. ISSN 0956-5361 . Pp. 183-232