Moundville Archaeological Site

Coordinates: 33 ° 0 ′ 10.2 ″ N , 87 ° 37 ′ 7.1 ″ W.

The Moundville Archaeological Site , also Moundville Archaeological Park , is an archaeological park or a 75 hectare site in the US state of Alabama . It was one of the largest settlements in the United States from pre-European times. It was about 20 km south of Tuscaloosa on the Black Warrior River , not far from today's city of Moundville . It is attributed to the Mississippi culture , is the second largest site of this culture after Cahokia , and existed between about 1000 and the 16th century. The city's heyday was between 1200 and 1350. Today's park contains the site with its mounds surrounding a plaza , a main square, a museum, an archaeological research center ( David L. DeJarnette Archaeological Research Center ), a nature park and a campsite . The archeology park is managed by the University of Alabama Museums and has approximately 40,000 visitors annually.

history

The 185 acre settlement was a planned city. The main square was artificially leveled and filled, the 29 mounds were built around it. They were between one and almost 20 m high. The loam brought in baskets was extracted from the area, and there are now small lakes at the excavation sites. The plaza , as such a central square is usually called, was free of residential developments, but remains of such development can be found on its edge, as well as along the picket fence that surrounded the city.

West Jefferson phase

The reason for building the city at the end of the woodland period is unknown. The phase before the city was created is known as the West Jefferson phase . It is characterized by numerous scattered settlements that were 0.2 to 0.5 hectares in size. Its inhabitants lived outside the flood phase between autumn and winter in the higher areas above the river, so spent the cold season far away from the river, while the warm season was close to the river. Although wild plants and hunting continued to be the livelihood, corn cultivation became increasingly important at the end of this phase.

The structure of the society is hardly known, especially since it was only possible to excavate a house from this period. Supplies were stored in pits below the surface. Long-distance trade relationships, as they later became so striking, existed only to a small extent and related to certain types of stone. Otherwise, this raw material requirement for tools was met almost entirely locally. However, shells ( snail shells , mussel shells ) of marine mollusks are already appearing , which have been processed further and which indicate trade relations with the Gulf of Mexico .

Moundville I

The settlement structure and the material culture changed almost suddenly around 1200. The surrounding, small settlements were largely abandoned, only a few "administrative centers" with flattened mounds emerged next to scattered courtyards. The only two platform mounds in the area were created in the Moundville area. This made Moundville stand out from the surrounding area, and even the settlement on the river was unique. In 1975, the so-called Asphalt Plant Mound immediately northeast of the Moundville site was investigated. A large number of artifacts were found, the materials of which could only have been brought in via long-distance trade.

Less is known about Mound X , which is to the southeast of the site. In 1984 it was found that the fortifications ran over this mound and that it had been destroyed when Moundville was founded. In the 1990s, two more early spots were found, the so-called Picnic Area and the East Conference Building . Four of the eight buildings found there could be assigned to Moundville I. These early houses did not have any internal structures such as benches, walls or support posts. One of them was sunk slightly into the ground. It had a clay platform that was found elsewhere near Moundville. It is unclear whether these structures can be interpreted as benches, but at least they disappear after Moundville I. On the other hand, in Moundville there is no other common phenomenon in the West Jefferson phase, namely the bell-shaped storage pits. From this it was concluded that there were already aboveground storage facilities.

Little stone was introduced except from Mill Creek , Illinois . This flint, the Mill Creek Chert , is associated with the corn harvest. Flint from Fort Bayne and Bangor in northern Alabama was used to improve the production of chips. When processing clay , the mollusc shell was given priority over pottery shards, which was only adopted in the distant area around a century later. Since no transition between West Jefferson and early Moundville I can be seen, there was speculation about the penetration of new groups, to which the new culture was accordingly based. At the moment, the question of whether the culture was created locally or through migrating groups cannot be answered.

Late Moundville I, Early Moundville II

Towards the end of the Moundville I phase, a system of chiefs (Moundville chiefdom) was established. While a leadership group was established in Moundville and a population influx allowed the city to grow, the rural surroundings became depopulated. The city was surrounded by a wall-like palisade fence, which was renewed at least six times by 1300. The plaza was leveled, the 29 mounds were built in the late Moundville I phase. At least four secondary centers were created, older mounds were abandoned. The secondary centers established a tax system and delivered maize to the next higher centers. By 1300 Moundville was the largest city in Alabama with a population of about one thousand.

Late Moundville II, Early Moundville III

Again a dramatic upheaval occurred. The fortifications were demolished, and only one group, often referred to as the elite, lived in the city, and their tasks are difficult to develop. At the same time, the rituals in Moundville became more complex, the additions more valuable and better worked out. It is believed that the higher the rank of this remaining core elite, the greater the required distance from the rest of the population. This moved back to small settlements on the river. Moundville became a necropolis . The catchment area of long-distance trade became smaller; Nothing is known about the non-elite groups.

Late Moundville III, Early Moundville IV

In this phase, traces of living can only be shown at three mounds, namely at mounds P, B and E in the north of the city. Only in the southwest of Mound G could it be shown that some people did not live on one of the mounds. On the other hand, the funeral rituals lived on outside the city, as did the mound construction. Moundville had completely lost its political and ultimately its ritual function.

Between 1300 and 1450, the mounds gradually fell out of use, and the place shrank. Apparently the former residents built settlements with only one mound each along the river. Moundville was increasingly becoming a burial site. Difficult to interpret symbols appeared on the artifacts, like a cross in a circle, hand and eye, winged snakes, skulls and bones, arrows. They may suggest that ancestors, war and death became increasingly important in religious life.

City structure and society

Some elements of the social structure can be read from the shape, the arrangement and above all the content of the mounds. In these, inhabited mounds alternated with those reserved for funerals. The largest living and burial mounds were on the north side of the main square. Mound A , whose function is not known, stood in the middle of the square.

Grave goods

Most of the deceased were buried in graves near their homes, and the vast majority were given simple burial objects such as tools. Some, probably higher-ranking people, lived on the flattened mounds and they were buried in smaller mounds with stone or copper artefacts, often also mollusc shells. Some of the adults were buried with copper axes; their skeletons were found in the northernmost burial mounds. The raw copper also came from distant areas, as did the mollusc shells. Some of the artifacts may represent wealth, while others were more indicative of rank or authority.

Conclusions about society, new approaches

In 1974, Peebles proposed that society consisted of a superordinate group and a subordinate group after examining over 2,000 grave sites. He believed he could recognize the former by their proximity to the mounds and by additions, criteria that about 5% of the dead satisfied. In addition, the mounds had been built in pairs, with two mounds belonging to a group that lived on one of the two hills and buried their dead under the other. These two functional assignments were spatially divided in such a way that the mounds in the east were assigned to those in the west. There was also the fact that vessels depicting frogs, bats, mollusc shells or fish were found in the east, while those with ducks were found in the west. Eventually from north to south the mounds became smaller and their equipment poorer. Mounds C and D, which were furthest to the north, contained the most complex traces of ritual and burial. At the north end of the plaza, Peebles identified public buildings and spaces where ball games were held. On the edge of the plaza, he also designated an ossuary and a sweat lodge . He distinguished three industrial activities in the city, namely skin processing (in the northeast of the city), pottery manufacture and the production of glass beads in connection with the processing of snail shells and mussel shells.

From other finds it was concluded that the society consisted of three classes, the low-ranking workers, a high-ranking management class and the copper ax bearers who could possibly be addressed as chiefs, a funerary gift that was rare.

This relatively abstract approach is increasingly being replaced by the observation of everyday life processes, insofar as they can be deciphered, and the interaction pattern that can be derived from them. Here, so the assumption, the social order can be seen much more clearly, which was much more differentiated than the mere hierarchization in a simple, strict scheme, which is based predominantly on economic and power-theoretical considerations, suggests. In the course of the 1990s, questions about the division of domestic and external work along gender lines, technological decision-making in the choice of tools and materials, techniques for preparing food or dealing with waste increasingly came to the fore.

Hierarchical societies with their leading elites, as they are under pressure to legitimize them, tend to give symbolic meaning to every everyday behavior, which in turn, in their constant repetition, brings to mind and perpetuates the form of society that is useful to them. Therefore, the arrangement of the mounds and the dwellings reflects the social inequality every day and thereby strengthens it. In this approach, people are not put in a position through excess production to feed other members of their society and thus free them from productive work, which in turn leads to rule, but the existing rule and exercise of power is initially enforced, then cultic and ritually integrated tax systems strengthened. For the researchers, however, this internal hierarchy does not begin at the top level, but in the household.

Exogamous kinship groups, the clans, existed alongside house groups and lineages. The clans had no wealth or land, their members were scattered in different places and they rarely appeared as a closed group. Moietys, in turn, regulated the ritual forms and secured marriage taboos, so that marriage was not allowed within these groups, so they were also exogamous. Sometimes one group handled matters of warfare and the other those of peace. Often the difference between them was of a ritual nature, and sometimes there was a difference in rank. The units below the clan level were often production and consumption communities that had rights to certain land areas and often lived together. These were the residential or house groups, whereby the house is to be understood in a broader sense. They often stood together in the form of several houses. With these considerations, studies of such households became much more far-reaching than mere studies of the mounds and grave goods. Between the overarching structures, it was also possible to identify an intermediate structure that was probably related to one another and consisted of house groups living close together. In strongly hierarchical societies, the groups that were assigned a higher rank were recognized by larger houses and by their exclusive proximity to certain ritually significant buildings. In complex societies like the one in Cahokia, this could mean that the groups that were not allowed to enter were excluded by a wall.

Rediscovery and excavations

When Hernando de Soto passed the area in 1540, only a few people lived in Moundville, but none of the villages described by the Spaniard can be identified with Moundville with certainty. When Europeans came to the area at the beginning of the 18th century, it was largely deserted.

Until 1869, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, none of the non-indigenous peoples paid much more attention to the hills except Sheriff Hezekiah K. Powell, who claimed to have found a giant, a man nine feet tall. But as early as 1840, the local planter Thomas Maxwell was digging in the hills. He reported to the Alabama Historical Society about 15 hills and a surrounding earthwork. The neighbors thought he was mad when he kept digging and found clay pots and arrowheads. Powell believed in a race, the enigmatic Mound Builders, who he believed had been exterminated by the Indians. In addition, the findings of giants seemed to confirm the Bible (Gen. 6.4) that giants walked the earth at that time.

Nathaniel T. Lupton, however, the fifth president of the University of Alabama , was more sober and mapped the site. He dug in the hill later called Mound O. Now the federal government intervened and dispatched excavators in 1882, but their activities are hardly documented. In 1883, Edward Palmer wanted to do another dig, but the local farmer asked for $ 100 for permission. That was too much money for the government and the dig was not carried out. In 1894 some results from excavations at other mounds were published and it was recognized that the builders of the mounds had been Indians.

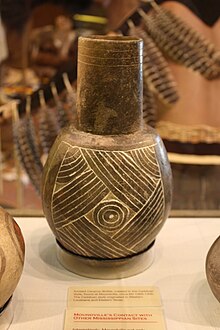

From 1905 the private collector Clarence B. Moore carried out several excavations, taking the most beautiful pots, stone pipes, axes and pallets - disc-shaped objects with traces of paint, as well as copper and mollusc bowls. He was a wealthy man from Philadelphia who had sailed south in his steamboat, The Gopher of Philadelphia , since 1891 . Moore stayed at the site for 36 days and returned for another month the next year. His scientific advisor was Dr. Milo Miller, who mapped the site and assigned letters to the mounds. The two men realized that there were two different types of mounds, those with buried people and mounds - the latter did not interest him, and after such a diagnosis he had the test drilling stopped immediately. Moore published a kind of picture book of the artifacts, mostly in the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia , finds that he brought to his hometown.

The state of Alabama fought against this with a law to protect antiquities that was passed in 1915. In the 1920s, citizens, above all the geologist Dr. Walter B. Jones to set up a park. Jones used his house to buy the site, and in 1933 Mound State Park , later called the Mound State Monument, was created. Today it covers an area of 320 acres.

Jones, with the help of David L. DeJarnette, began his first scientific research in 1929. As in many places, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was used to build roads and a museum. More than 2000 graves, 75 remains of houses and thousands of artifacts were unearthed by 1941.

DeJarnette became director of the park and founding member of the university's Department of Anthropology in the 1950s. For two decades he was the leading archaeologist in the state. On July 19, 1964, the park received the status of a National Historic Landmark . In October 1966, the park was listed as a site on the National Register of Historic Places . At the end of the 1960s, the professor at Indiana University Christopher S. Peebles and his students examined the enormous masses of finds collected by the unemployed during the global economic crisis . A DeJarnett student, Vernon J. Knight Jr. of the University of Alabama, dug more mounds in the 1990s.

So far only about 14% of the total area has been examined. Every year in early October, a festival with ceremonies takes place in the park, the Moundville Native American Festival, organized by the surrounding tribes .

literature

- John Howard Blitz: Moundville , Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008.

- Vernon James Knight Jr., Vincas P. Steponaitis: A New History of Moundville , in: The Archeology of the Moundville Chiefdom, ed. by Vernon James Knight Jr. and Vincas P. Steponaitis, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

- Vernon James Knight Jr. (Ed.): The Moundville Expeditions of Clarence Bloomfield Moore , Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1996.

- Vernon James Knight Jr .: Mound Excavations at Moundville: Architecture, Elites and Social Order , University of Alabama Press, 2010.

- Gregory D. Wilson: The Archeology of Everyday Life at Early Moundville , University of Alabama Press, 2008.

Web links

- Moundville , in: Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Moundville Archaeological Park

Remarks

- ^ John Howard Blitz: Moundville , Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008, p. 8.

- ^ John Howard Blitz: Moundville , Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State: Alabama. National Park Service , accessed March 20, 2020.

- ^ Moundville on the National Register Information System. National Park Service , accessed March 20, 2020.