Big Five (psychology)

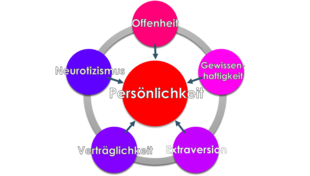

The Big Five (also five-factor model , FFM) is a model of personality psychology . In English it is also referred to as the OCEAN model (after the corresponding initials Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism ).

According to him, there are five main dimensions of personality and every person can be classified on the following scales:

- Openness to experience (open-mindedness),

- Conscientiousness (perfectionism),

- Extraversion (socializing),

- Compatibility (consideration, willingness to cooperate , empathy ) and

- Neuroticism (emotional instability and vulnerability).

The development of the Big Five began in the 1930s with the lexical approach adopted by Louis Thurstone , Gordon Allport and Henry Sebastian Odbert. This is based on the view that personality traits are reflected in language; d. H. it is assumed that all essential differences between people are already represented in the dictionary by corresponding terms. On the basis of lists with over 18,000 terms, factor analysis found five very stable, independent and largely culturally stable factors: the Big Five .

The Big Five were later proven by a large number of studies and are now internationally recognized as the universal standard model in personality research. They have been used in over 3,000 scientific studies over the past twenty years.

The five factors

The five-factor model of personality has a long history of development. This has contributed to the fact that the factors have been given different names and the descriptions of the individual factors differ slightly from author to author. The following description of the factors is based on the formulations of the test authors Costa and McCrae after the translation by Borkenau and Ostendorf. The descriptions result from studies on both self and external assessments.

In this context, a high or low score means that the person's values differ significantly from the average of the respective norm sample ( norm value ). However, people with a high or low score in one of the factors do not necessarily have all the features that are characteristic of the scale.

| Abbreviation | factor | weakly pronounced | strongly pronounced |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | Openness to experience | conservative, careful | inventive, curious |

| C. | conscientiousness | carefree, careless | effective, organized |

| E. | Extraversion | reserved, reserved | sociable |

| A. | compatibility | competitive, antagonistic | cooperative, kind, compassionate |

| N | Neuroticism | confident, calm | emotional, vulnerable |

openness

This factor describes the interest and the extent to which they are occupied with new experiences, experiences and impressions.

- People with high openness values often state that they have a lively imagination, clearly perceive their positive and negative feelings and are interested in many personal and public events. You describe yourself as inquisitive, intellectual, imaginative, keen to experiment and artistically interested. They are more willing to critically question existing norms and to respond to new social, ethical and political values. They are independent in their judgment, often behave unconventionally, try out new ways of acting and prefer variety.

- In contrast, people with low levels of openness tend to behave more conventionally and adopt conservative attitudes . They prefer the familiar and the tried and tested to the new and they perceive their emotional reactions to be rather subdued.

conscientiousness

This factor primarily describes the degree of self-control , accuracy and determination.

- People with high conscientiousness values act in an organized, careful, planning, effective, responsible, reliable and considered manner.

- People with low conscientiousness scores act carelessly, spontaneously, and imprecisely.

Extraversion

This factor describes activity and interpersonal behavior. It is also sometimes called enthusiasm (English: surgency ).

- People with high extraversion scores are sociable, active, talkative, person-oriented, warm, optimistic and cheerful. They are also receptive to suggestions and excitement.

- Introverts are reluctant to socialize, like being alone and independent. They can also be very active, but less in company.

compatibility

Like extraversion, compatibility is primarily a factor that describes interpersonal behavior.

- A central characteristic of people with high tolerance values is their altruism . They treat others with understanding, benevolence, and compassion ; they strive to help others, and they are convinced that they will act equally helpful. They tend towards interpersonal trust, cooperativity and indulgence.

- In contrast, people with low tolerance values describe themselves as argumentative, self-centered , suspicious and antagonistic towards other people's intentions. They are more competitive than cooperative.

The compatible side of the dimension seems to be more socially desirable. However, it should not be forgotten that the ability to fight for one's own interests is helpful in many situations. For example, compatibility in court is not necessarily a virtue.

Neuroticism

This factor reflects individual differences in the experience of negative emotions and is also referred to by some authors as emotional lability . The opposite pole is also known as emotional stability , contentment or ego strength.

- People with a high level of neuroticism are more likely to experience fear, nervousness, tension, sadness, insecurity, and embarrassment. In addition, these sensations persist longer and are more easily triggered. They tend to be more concerned about their health, have unrealistic ideas, and have difficulty responding appropriately in stressful situations .

- People with low neuroticism scores are more likely to be calm, content, stable, relaxed, and safe. You experience negative feelings less often. Low values are not necessarily associated with experiencing positive emotions.

Heredity

Heritability (symbol:) is a measure of the heritability of properties. About half of the interpersonal differences in the characteristics of the Big Five can be explained by the influence of genes. The heritability of the Big Five is therefore around 0.5:

- Neuroticism: ≈48%

- Extraversion: ≈54%

- Openness to experience: ≈57%

- Conscientiousness: ≈49%

- Tolerance: ≈42%

The error is around 5–10 percentage points, the remaining 40–45% are therefore environmental factors. It should be noted here that the environment shared with others (e.g. family income) has hardly any influence, only the individual environment (e.g. individual friends, accidents). More recent twin studies come to the conclusion that up to two thirds of the measurable personality traits can be traced back to genetic influences.

Development aspect

Correlative studies found that the positions within the dimensions fluctuate greatly in childhood and adolescence. Only after the age of 30 do the values remain largely constant. The causes of the manifestations are on the one hand genetic factors, on the other hand they depend on the individually perceived social environment.

More recent studies show that the assumption of the five-factor theory that personality development ends at the age of 30 is not fundamentally tenable. After the phase of youth, a stable phase is actually reached at the age of 30. However, in old age a change in personality comparable to that of young adulthood becomes visible again. This seems to be due in particular to life experience and social circumstances. There are particularly significant increases with age for conscientiousness and tolerance. The values for openness decrease with age.

In terms of personality types, the number of so-called resilients and overcontrolled people increase significantly. Even after the age of seventy, up to 25% of people change their previous personality type within four years, which in some cases strongly correlates with gender and type. In order to explain the changes, it was crucial that the subjective age in self-perception and perception of others, the distance to the real or expected end of life, and the biological age were given more consideration than the chronological age.

Diagnosis

The Big Five are usually recorded using questionnaires ; objective personality tests are also used less often .

The most frequently used test for adolescents and adults is the NEO-PI-R (NEO personality inventory, revised version) by Paul T. Costa and Robert R. McCrae , the German-language version of the multidimensional personality inventory was developed by Fritz Ostendorf and Alois Angleitner .

“NEO” is an acronym made up of the first letters of three personality factors contained in the model. It is about:

- Neuroticism (N),

- Extraversion (E) and

- Openness to experience (O) (ger .: openness to experience ).

These three NEO factors, detailed above, together with

- Conscientiousness (C) (ger .: conscientiousness ) and

- Compatibility (A) (ger .: agreeableness )

the big five.

The NEO-PI-R is a very comprehensive test with 240 items, so that the five factors can each be divided into six sub-scales, also called facets:

- Neuroticism: Anxiety, irritability, depression, social bias, impulsivity, and vulnerability

- Extraversion: warmth, sociability, assertiveness, activity, hunger for adventure and cheerfulness

- Openness: in each case openness to fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, actions, ideas and with regard to the system of standards and values

- Conscientiousness: Competence, neatness, sense of duty, striving for achievement, self-discipline and prudence

- Compatibility: trust, candor, altruism, accommodating, modesty and kindness

Each question in the test is answered using a five-point Likert scale . During the evaluation, point sums are calculated for each of the dimensions and compared with the standard values in the manual. When calculating the total values, some questions are evaluated in the opposite way due to the formulation. A positive value then goes negative, a negative value positive in the scale total value.

In addition to the classic paper-and-pencil version, there are also computer-based versions. For example, the computer-aided NEO-PI-R + , which records additional dimensions that are relevant for specialists and managers. The aim of this version is a professional and personnel development-related evaluation, e.g. B. in terms of potential advice.

The processing time of the NEO-PI-R averages 35 minutes, which can be too long depending on the context. This is why Costa and McCrae developed the short version NEO-FFI (NEO five-factor inventory; German-language version by Peter Borkenau and Fritz Ostendorf) with 60 items and an average processing time of 10 minutes. The NEO-FFI only records the 5 main factors; a differentiation of the facets is not possible due to the small number of items.

The test quality criteria for the long version (NEO-PI-R) and the short version (NEO-FFI) have been researched in numerous studies, so that the procedures are viewed as objective , reliable and valid (effective, valid).

The classic NEO-PI-R and NEO-FFI procedures are published by test publishers (in German-speaking countries e.g. by Hogrefe Verlag ), so that their use is not free and must be paid for accordingly. The International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) offers an alternative, which provides freely accessible items for personality tests. Procedures for the Big Five can also be compiled from this pool. For example, German-language versions of the Big Five with 50, 100 and 300 items were developed.

Alternative models

On the basis of the Big Five, more or fewer personality factors can be identified through factor analysis. Examples of this are: A reduction of the Big Five to three factors (extraversion, tolerance, conscientiousness); a two-factor model, consisting of stability (summary of high tolerance, high conscientiousness and low neuroticism) and plasticity (summary of high extraversion and high openness to experience); as well as a one-factor model, which in some ways reflects a positively or negatively assessed personality. However, none of these models was able to prevail against the Big Five.

The most important alternative to the Big Five is the HEXACO model , which is the subject of numerous studies. This adds the sixth factor of honesty and modesty to the Big Five . This honesty and modesty is measured in the Big Five within the compatibility factor (in the NEO-PI-R with the facets of frankness and modesty ), but in the HEXACO it is decoupled as a separate, independent factor. In addition, the long form of the HEXACO-PI-R test uses slightly different facets (subscales) for all factors compared to the long form of the NEO-PI-R test.

Application (selection)

In the presidential election in the United States in November 2016 and in the referendum in Great Britain on leaving the European Union in July 2016 (" Brexit "), the two surprising winners each engaged the Cambridge Analytica company , which deals with survey, evaluation and application and the allocation and sale of personal data obtained mainly on the Internet and uses methods of psychometrics , an offshoot of psychology ( see also Big Data , Direct Marketing and Psychography ). According to her own statements, she has personality profiles based on the Big Five of 220 million adults in the USA alone and used them for personalized advertising during the election campaign. Later, however, executives publicly admitted that no personality profiles were created for Trump's election campaign and the company spokesman also withdrew the statement that he had supported the Brexit campaign Leave.eu .

criticism

Critics of the model doubt that it is able to adequately describe individual personalities. In addition, the factors are neither universally nor at least comprehensively proven in Western nations.

literature

- Gordon Allport , Henry Sebastian Odbert: Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study . Psychological Monographs, Whole No. 211, 1936, pp. 171 (English).

- Dirk Hagemann, Frank M. Spinath , Dieter Bartussek, Manfred Amelang, Gerhard Stemmler : Differential Psychology and Personality Research . Kohlhammer Verlag , 2016, ISBN 978-3-17-025723-8 , pp. 694 .

- Jens Asendorpf , Franz J. Neyer: Psychology of personality . 5th edition. Springer, 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-30263-3 , pp. 455 .

- Borkenau, P. & Ostendorf, F. (1993). NEO five factor inventory (NEO-FFI) according to Costa and McCrae (pp. 5–10, 27–28). Hogrefe.

- De Raad, B. (1998). Five big, big five issues: Rationale, content, structure, status, and crosscultural assessment . European Psychologist, 3, 113-124.

- Lorber, L. (2013). Knowledge of human nature - the big type test: How to decipher the strengths and weaknesses . CH Beck.

- Nettle, D. (2012) Personality - Why You Are The Way You Are . Anaconda.

- John, OP, Naumann, LP & Soto, CJ: (2008) Paradigm Shift to the Integrative Big Five Trait Taxonomy . Handbook of Personality Theory and Research. 3. Edition. Pp. 114-158

- Daniel Cervone, Oliver P. John, Lawrence A. Pervin: Personality Theories . 5th edition. UTB. 2005. ISBN 978-3-8252-8035-2 .

- Thomas Saum-Aldehoff: Big Five - Knowing yourself and others . Patmos. 2007.

Web links

- Jochen Paulus : The five times one in psychology . In: Wissen , SWR2 , October 14, 2009 (audio; 27:31 min.).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Oliver P. John, Laura P. Naumann, Christopher J. Soto: (2008) Paradigm Shift to the Integrative Big Five Trait Taxonomy . Handbook of Personality Theory and Research. 3. Edition. Pp. 114-117

- ^ Asendorpf, JB & Neyer, FJ (2012). Psychology of Personality. Berlin: Springer.

- ↑ M. Amelang & D. Bartussek: Differential Psychology and Personality Research. (5th ed.). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2001, p. 370

- ↑ P. Borkenau & F. Ostendorf: NEO five-factor inventory according to Costa and McCrae (NEO-FFI). Manual (2nd ed.). Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2008.

- ↑ Bouchard & McGue, 2003. Genetic and environmental influences on human psychological differences. Journal of Neurobiology, 54, 4-45. doi : 10.1002 / new.10160 .

- ^ Christian Kandler, Rainer Riemann, Frank M. Spinath, Alois Angleitner; 2010. Sources of Variance in Personality Facets: A Multiple-Rater Twin Study of Self-Peer, Peer-Peer, and Self-Self (Dis) Agreement. Journal of Personality

- ^ Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, SC (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 862-882.

- ↑ Jule Specht: Psychology of old age. In: Hochbetagt, APUZ, 65th year, 38–39 / 2015, September 14, 2015, p. 6ff. [1]

- ↑ http://ipip.ori.org/ International Personality Item Pool

- ↑ https://ipip.ori.org/newitemtranslations.htm International Personality Item Pool: Versions in different languages

- ↑ Herzberg, PY & Roth, M. (2014). Personality psychology . Jumper. Pp. 46-48

- ↑ http://hexaco.org/references

- ^ Lee, K. & Ashton, MC (2004): Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory . Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 329-358.

- ↑ Hannes Grassegger, Mikael Krogerus: I only showed that the bomb exists . In: The magazine . Issue 48, December 3, 2016.

- ↑ Peter Welchering : Politics 4.0: Online manipulation of voters . In: deutschlandfunk.de , Computer and Communication . December 10, 2016.

- ↑ US Election: The Cambridge Analytica Air Pumps . March 8, 2017 ( golem.de [accessed April 5, 2017]).

- ↑ The Brockhaus Psychologie (ed. By the lexicon editors of the publishing house FA Brockhaus): Psychologie. Understand feeling, thinking and behavior. 2nd Edition. Leipzig, Mannheim, FA Brockhaus 2009, ISBN 978-3-7653-0592-4 , p. 192 (referring, without proof)