Nanuk, the Eskimo

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Nanuk, the Eskimo |

| Original title | Nanook of the North |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1922 |

| length | 78 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 6 |

| Rod | |

| Director | Robert J. Flaherty |

| script | Robert J. Flaherty |

| production | Robert J. Flaherty |

| music | Rudolf Schramm |

| camera | Robert J. Flaherty |

| cut | Robert J. Flaherty, Charles Yellow |

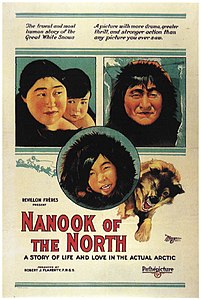

Nanuk, the Eskimo (original title: Nanook of the North ) was the first long American documentary film to delight a wide audience; it was produced by Robert J. Flaherty in 1922. The film is considered to be one of the most important documentaries of the silent film era and is often incorrectly referred to as the first full-length documentary. In fact, the first documentary films with a running time of over 60 minutes were made by the German mountain film pioneer Arnold Fanck ( Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs , D 1919/20; Im Kampf mit dem Berge , D 1920/21). In addition, the film is called the first ethnographic film by some authors .

action

The film follows the Eskimo Nanuk and his family, which consists of the two wives Nyla and Cunayou, the young son Allee and the four-month baby Rainbow , for several weeks . Everyday life and work are documented, such as seal and walrus hunting, fishing, building igloos, fur trade, caring for the children and looking after the sled dogs. In addition to the beauty of nature and the naive cheerfulness of people, the harshness of arctic life is also shown. The family is in mortal danger in a sudden snow storm, and they are plagued by hunger and desperation.

background

Flaherty made the documentary about the everyday life of the Inuit family of Nanuk and Nyla near the town of Inukjuaq in the Arctic of Quebec, Canada. Flaherty worked as a prospector in this region and also made film recordings, which he showed in Toronto in private screenings from 1916. While shipping, the material ignited from 9,000 meters when Flaherty accidentally dropped cigarette ash on the flammable films. Flaherty made new recordings - supported by Revillon Frères - from August 1920 to August 1921.

Controversy

Flaherty has been criticized for deceptively portraying staged events as reality in his film. “Nanuk” was actually called Allakariallak. Flaherty chose this name because of its apparent authenticity, which makes it more marketable to the Euro-American audience. The "wife" shown in the film wasn't actually Nanuk's wife either. According to Charlie Nayoumealuk, interviewed in Nanook Revisited (1990), the two women in the film - Nyla (Alice [?] Nuvalinga) and Cunayou (whose real name is unknown) - were not Allakariallak's wives, but were in a wild marriage Flaherty. And although Allakariallak usually used a rifle when hunting, Flaherty suggested that he hunt like his ancestors did in order to capture the Inuit way of life before European colonization of America. By the 1920s, by the time Nanuk was being filmed, the Inuit had already begun to wear Western clothing and rifles were used rather than harpoons for hunting . This fact later met with criticism from supporters of the Cinéma vérité . Flaherty also exaggerated the dangers to the Inuit hunters by repeatedly claiming that Allakariallak died of starvation less than two years after the film was completed, although he died at home - probably of tuberculosis.

In addition, the film has been criticized for portraying Inuit as subhuman arctic beings with no technology or culture. This reproduces stereotypical images of arctic peoples in Western imaginations that position them outside of modern history. In one of the scenes Nanuk and his family go to a trading post in a kayak because Nanuk wants to trade fox, seal and polar bear skins from the white trader. When the two cultures meet, there is an interaction. The dealer plays music on a gramophone and tries to explain how one can “preserve” his voice. Nanuk stares at the device and approaches his ear as the dealer cranks again. The dealer finally removes the record and hands it to Nanook, who looks at it first, then puts it in his mouth and bites into it. The purpose of the scene is to get the audience to laugh at the naivety of Nanuk and people isolated from Western culture. It serves as confirmation for the audience that the "primitive" indigenous person is less than the "modern" Western person - less civilized and less intelligent. Prejudices of this kind are often used in colonialism to legitimize the supremacy of the colonizers. In reality the scene was completely scripted and Allakariallak knew what a gramophone was. The film was also criticized for comparing Inuit to animals. The film is considered an artefact of popular culture at that time and also as the result of a historical fascination for Inuit actors in exhibitions, zoos, fairs, museums and in early cinema.

In the 1980s the film, which for a long time was only shown in a 48-minute version, was restored.

Awards

The film was entered into the National Film Registry in 1989.

literature

- RJ Christopher: Through Canada's Northland. The Arctic Photography of Robert J. Flaherty. In: JCH King, H. Lidchi (Ed.): Imaging the Arctic. London 1998.

- Richard Peña: Nanuk, the Eskimo. Nanook of the North (1922). In: Steven Jay Schneider (Ed.): 1001 films. Edition Olms, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-283-00497-8 , pp. 44–45.

- Paul Rotha : Robert J. Flaherty. A biography. Jay Ruby (Ed.), University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 1983.

- Fatimah Tobing Rony: The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle . Duke University Press, Durham and London 1996.

Web links

- Nanook of the North in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Gold review of Nanuk the Eskimo on FilmSzene.de

- Film review by Roger Ebert at suntimes.com, September 25, 2005 (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fatimah Tobing Rony: The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle . Duke University Press, 1996, p. 99. Retrieved July 30, 2017.

- ↑ a b Fatimah Tobing Rony: The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle . Duke University Press, Durham / London 1996, p. 99 .

- ↑ Richard Peña: Nanuk, the Eskimo. Nanook of the North (1922). In: Steven Jay Schneider (Ed.): 1001 films. Edition Olms, Zurich 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Richard Leacock: On Working With Robert and Frances Flaherty. April 26, 1990, accessed May 24, 2020 (English, essay by Richard Leacock, Flaherty's cameraman and later MIT professor of film studies).

- ↑ Fatimah Tobing Rony: The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle . Duke University Press, Durham / London 1996, p. 104 .

- ↑ Julia V. Emberley: Defamiliarizing the Aboriginal: Cultural Practices and decolonization in Canada . University of Toronto Press, Toronto 2007, p. 86 (cited here by Fatimah Tobing Rony, Taxidermy and Romantic Ethnography: Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North).

- ↑ Dean W. Duncan: Nanook of the North. In: Criterion. Retrieved May 24, 2020 .

- ↑ Pamela R. Stern: Historical dictionary of the Inuit . Scarecrow Press, Lanham 2004, p. 23 .

- ^ Robert J. Christopher: Robert and Frances Flaherty: A Documentary Life, 1883-1922. McGill-Queen's University Press, Montréal / Kingston 2005, pp. 387-388 .

- ↑ Joseph E. Senungetuk: Give or Take a Century: An Eskimo Chronicle . The Indian Historian Press, San Francisco 1971, p. 25 .

- ↑ Fatimah Tobing Rony: The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle . Duke University Press, Durham / London 1996, p. 112 .

- ^ William Rothman: Documentary film classics . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1997, pp. 9-11 .