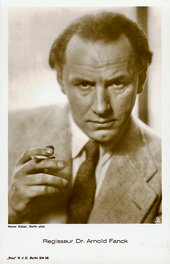

Arnold Fanck

Arnold Heinrich Fanck (born March 6, 1889 in Frankenthal , Rheinpfalz ; † September 28, 1974 in Freiburg im Breisgau ) was a German geologist , photographer , inventor , film actor , cameraman , film producer , screenwriter and book author, and film director . Along side Sepp Allgeier worldwide as a pioneer of the mountain , sports , skiing and nature film, along with Allgeier as the inventor of mountain films and the film genre of the same name.

Leni Riefenstahl , who described Fanck's work as artistic and avant-garde , later adapted the techniques and camera positions developed by Fanck's Freiburg school in principle and in detail as a film director .

The broad-based development of skiing and the skiing industry that began afterwards, as well as mountaineering in the high mountains, which developed in a similar way, was largely attributed to the broad impact of Fanck's mountain and mountain sports films by the Freiburg School in the 1920s.

family

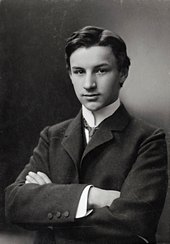

Arnold Heinrich Fanck was the fifth child of the ( Roman Catholic ) director of the Frankenthal AG sugar factory and royal councilor Christoph Friedrich Fanck (born December 4, 1846 in Emmendingen ; † June 16, 1906 in Frankenthal ) and his ( Protestant ) wife Karolina Ida ( * January 10, 1858 in Munich ; † May 16, 1957 in Frankenthal ), née Paraquin. His mother was the daughter of the Frankenthal-based notary Ernst Paraquin (* July 1, 1815, † February 2, 1876) and his wife Amalie Petersen (* October 27, 1826 in Landau, † January 15, 1877). The Paraquin family probably descended from Italian immigrants.

Arnold had four older siblings, Marie (* August 24, 1882 in Frankenthal), Ernst (* January 18, 1884 in Frankenthal; † July 31, 1884 there), Helene (* November 21, 1886 in Frankenthal; † December 4, 1979 ) and Ernestine Elisabeth (born March 23, 1888 in Frankenthal; † April 15, 1940 in Nuremberg ), of whom his older brother Ernst died a few months after he was born.

On May 20, 1920, the 31-year-old Arnold Fanck married in Zurich the two years older chemist Natalia "Natuschka" Anna, (born July 9, 1887 in Nałęczów near Lublin ; † July 1, 1928), née Zaremba, a former fellow student. She was the daughter of a doctorate lawyer Roman Zaremba Maksymilian (1844-1914) and his wife Felicia (1868-1928), born Piotrowska, from Lublin. The marriage remained childless, Natalia Fanck fell ill with cancer soon after the wedding and died at the age of 40.

Fanck's first son Arnold Ernst from a premarital relationship with his mother Karolina Ida Fanck's domestic servant, Sophie Meder, was born in 1919 and later adopted by him. From 1930 to 1938 his father made it possible for him to visit the reform-pedagogical rural education home Freie Schulgemeinde in Wickersdorf near Saalfeld in the Thuringian Forest , where he passed his Abitur.

On September 22, 1934, Arnold Fanck married the AAFA secretary Elisabeth "Lisa" Kind (1908–1995) for the second time . From this marriage his second son Hans-Joachim (February 28, 1935; † 2015) emerged. The marriage ended in divorce in 1957. In 1972, Arnold Fanck married the speech therapist Ute Dietrich (1940–1991) in Freiburg im Breisgau .

Arnold Fanck lived in a rented apartment in Berlin's Kaiserallee 33/34 (today: Bundesallee ) in Berlin-Wilmersdorf from around 1929 to 1934 . In 1934 Fanck rented the villa at Am Sandwerder 39 in Berlin-Nikolassee, planned by architect Heinrich Schweitzer in the style of New Objectivity in 1928/29 for his second marriage . The interior of the villa, which is now a listed building, was redesigned by Arnold Fanck with film cutting and projection rooms for his professional needs.

The property belonged to the Jewish family of the doctorate in medicine and researcher Bruno Mendel , who had already emigrated in 1933 because of the transfer of power to the National Socialists .

Oskar Guttmann, who was commissioned by the Mendel family to manage the property, urged Fanck from 1938 to purchase the villa and property in the context of the “ Aryanization ”. The estimated purchase price of 80,000 Reichsmarks , which Fanck raised by 1939, was a major hurdle for him, since his film making had more or less come to a standstill due to his distance from the NSDAP by Joseph Goebbels ' ban.

Arnold Fanck's sons Arnold Ernst (also: Arnold junior) and Hans-Joachim (also: Hans or "Hänschen") both appeared as toddlers in their father's films. After graduating from high school, Arnold Ernst Fanck worked as a camera assistant and set photographer, possibly also as an extra , in at least one of his father's films.

From 1925 to 1933 Arnold Fanck's nephew, who later became the architect Ernst Petersen , worked on some of his films.

The Reich judge Julius Petersen sen. and his son of the same name, the literary scholar Julius Petersen jun. like the doctor Julius August Franz Bettinger (1802–1887) and Julius Bettinger (1879–1923) are related to the Fancks through Arnold Fanck's mother Karolina Ida.

Career

School, study and training

In his childhood Arnold Fanck was ailing, suffered from tuberculosis (Tbc), chronic bronchitis , asthma , associated attacks of suffocation, cramps and panic attacks : "Fear - fear of everything that arouses me - that was the main focus of my childhood". He did not attend elementary school, but received private lessons. By the age of about ten, he was too weak to walk properly. A doctor recommended that his parents send the boy to Davos ( Canton of Graubünden ) in Switzerland, where he stayed for four years from 1899 to 1903 and attended the Fridericianum , a sanatorium for pupils with lung disease with a high school boarding school. The local climate and sporting activity had a very positive effect on the boy's health; he learned to ski , climbed the mountains, toboggan and played ice hockey enthusiastically . As a result he developed a longing for the high mountains ; It was difficult for him to return to his native Frankenthal after four years in Davos. The high mountains became the center of his life.

After finishing secondary school at Easter 1906 at the Progymnasium in Frankenthal (today: Albert-Einstein-Gymnasium ), the year in which his father died, Arnold Fanck passed his matriculation exam at Easter 1909 at the humanistic Berthold-Gymnasium in Freiburg im Breisgau, where the Family moved away after father's death. Then he traveled to Norway.

He then studied art history and philosophy at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich and at the Friedrich Wilhelms University in Berlin . From 1911 he studied at the University of Zurich in the fields of geology and chemistry , interrupted in the winter semester 1911/12 by a semester at the Albert-Ludwigs-University in Freiburg. From 1913 to 1915 he continued his studies in Zurich, where Fanck prepared and completed a dissertation entitled The seamless deformation of fossils by tectonic pressure and its influence on the determination of species via fossils of the St. Gallen marine molasses . Since the manuscript was lost in 1918 during the turmoil of the November Revolution in Berlin, he submitted the dissertation supervised by Albert Heim a decade later in abridged form to Hans Schardt at the University of Zurich , and received his doctorate with it in 1929 .

Fanck, who took photographs, came into contact with the medium of film in 1913 through the Freiburg businessman, textile engineer and film pioneer Bernhard Gotthart (1871–1950). Gotthart founded Express Films Co. mbH in 1910, which subsequently became the most important manufacturer of documentary films in southern Germany. Fanck, who was already experienced in mountaineering and skiing, worked as a ski instructor in addition to his studies, worked with a group of young people on Gotthart's film 4,628 meters high on skis - with skis and film camera in 1913 on Monte Rosa and helped to carry the cinematic equipment up the mountain. Alongside Odo Deodatus I. Tauern , he got to know Sepp Allgeier , who was six years his junior and who operated the camera for his brother-in-law Gotthart's team, and was the first to ski and direct.

From Zurich, Studiosus Fanck, together with his one year younger, but more experienced mountaineering friend, Hans Eduard Rohde (1890–1915) and Walter Schaufelberger , had devoted himself entirely to mountaineering from 1911 onwards; they were formulated as “ mountain vagabonds ” or “ friends on a rope” ". Arnold Fanck was looking for adventure as well as the challenge of extreme conditions, overcame the fears of his childhood and, also in view of the rudimentary equipment at the time, accepted high risks. Together with Rohde, who is characterized as a daredevil, he completed a first winter ascent of the Matterhorn over the Zmuttgrat when he was 22 years old .

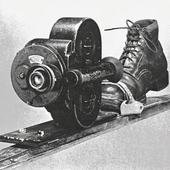

After the end of the war, Arnold Fanck worked temporarily as a carpet dealer in Berlin in 1919. With the proceeds from this, Fanck managed to buy his first film camera, a crank camera, recording cinema model A in a wooden housing produced by Heinrich Ernemann AG , which Sepp Allgeier instructed him in how to operate. The unheard-of subsequently happened: Fanck took the bulky film camera from its tripod ; he “ unleashed ” her, so to speak, and took her out of the studio into the open air, into nature, into the mountains - even in winter. Fanck's photographic gaze and his photographic know-how were retained and decisively determined his cinematic work. He became an avant-garde of the New Objectivity and was much closer to it than the genre of mountain films would suggest.

Military service

First World War

At the beginning of the First World War , Arnold Fanck volunteered as a war volunteer , but was retired due to his asthma. The generally prevailing patriotic urge at that time to want to stand up for the fatherland resulted in his feeling that he had to prove himself to be particularly masculine as an alternative in order to compensate for the disgrace of not being employed at the front.

After another spa stay in Davos, he completed a one-year training as a paramedic. Instead of being able to apply them, he was brokered by Major General Friedrich Wilhelm Albert Rohde (1850-ca. 1920), the father of his student and friend Hans Eduard Rohde, a photographic section of the scientific division III b of counterintelligence of the Imperial Army under Walter Nicolai abkommandiert . This worked for the intelligence department of the General Staff , from 1917 the Foreign Armies department .

During his work, Fanck developed various photographic apparatus and techniques, forged images of photos and, with the help of super slow motion, researched, for example, the penetration power of grenades on armor plates . He documented a method he invented for forging stamps in a short film of strung together photographic recordings.

This time of experimentation with high technology may be the starting point for Fanck's enthusiasm for technology, but also for his love of experimentation. In the meantime, he felt that single-image photography was too static, because he could not use it to depict the movement that was very important to him.

In the course of his work, he met Elsbeth Schragmüller , a top agent with a doctorate , better known as " Mademoiselle Docteur ", "Fräulein Doktor", "Fair Lady", "La Baronne" or "Mademoiselle Schwartz". This was led by the agent Margaretha Geertruida cell, world-famous as " Mata Hari ". However, after 1933 Fanck was unable to realize his planned film project about Schragmüller in the Nazi state ; Instead, film director Georg Wilhelm Pabst took over this subject and shot in France in 1935/36, the country against which her agent activities were directed.

Second World War

In 1944/45 Fanck worked briefly for the " Abwehr ", which at that time was already subordinate to the SD and then to the " Gestapo ". Through this activity it was possible for him to issue a manipulated marching order . With this, the 55-year-old managed to leave the embattled capital of the Reich and make his way to Höchenschwand in southern Baden , after he had been ordered to participate in the “ Volkssturm ” in the last months of the Second World War but did not want to take part. In Höchenschwand, both his second wife and his youngest son were housed in the household of a doctor friend.

Cinematic work

Weimar Republic

In 1920 Fanck founded the Berg- und Sport-Film GmbH together with the ethnologist Odo Deodatus I. Tauern in the mountain hut of the Academic Skiclub Freiburg (ASCF) on the Feldberg , to which the researcher Rolf Bauer and the Doctor Bernhard Villinger involved. A firm part of his film company was Sepp Allgeier as the first cameraman.

“The big - for me the only - means [...] offered the film. It is only through the language of the film that one can address the whole people, indeed peoples. And above all - only the film can show nature and life in nature with the highest attainable reality and liveliness. This was exactly what I needed: to show nature as it is, so beautiful and fertile, so idyllic and dramatic, so sunny and so gloomy, rigid and agitated - simply to convey the experience of nature - that was the task that I had asked myself when I turned from the natural sciences to natural cinematography. "

Fanck stood out as a filmmaker, among other things, because he always appeared with his academic title and even his artist postcards with “Dr. Fanck ”signed, probably to emphasize the authenticity and scientific nature of his cinematic works.

As the star actor in his films, he and his extraordinarily daring and lively Black Forest skiers, who at that time were skiing (contemporary: "snowshoes") made of wood with rudimentary bindings , engaged the doctor Ernst Baader junior (1894 ) , who was then the best German skier at the time –1953), and also the best Austrian skier Hannes Schneider vom Arlberg .

Mountaineering and skiing skills were the basic requirements for the team involved in Fanck's mountain films. The fact that the Black Forest ski athletes and mountaineers were partly identical to Fanck's cameramen has almost been forgotten today. Based on Fanck's own liberation from physical and psychological limitations in childhood, the capable and active (athletic) body became a focal point in Fanck's films; he was engaged in movement studies.

"[...] a film genre which was exclusively German: the mountain films. Dr. Arnold Fanck, a native of Freiburg i. Br., Discovered this genre and all but monopolized it throughout the republican era. He was originally a geologist infatuated with mountain climbing. In his zeal for spreading the gospel of proud peaks and perilous ascents, Fanck relied increasingly on actors and technicians who were, or became, outstanding alpinists and skiers. "

As an enthusiastic skier and mountaineer, Fanck felt called to bring the beauty of the mountain world and the fascination of skiing closer to a large audience: “And when I saw all these wonders for the first time, the snowy nature, it grabbed me and I told me, my God, you have to show that to everyone ”. It was his primary interest to document this authentically. At the same time he composed the mountain world on film based on artistic models that Caspar David Friedrich had created.

"The actual leading actor in his [Arnold Fancks] films were the mountains, which he staged with unprecedented precision and drama."

Together with the cameramen Richard Angst , Albert Benitz , Kurt Neubert , Walter Riml and Hans Schneeberger , Allgeier and Fanck belonged to the Freiburg School and made Freiburg im Breisgau a center of German filmmaking at the time.

Since there was no media-scientifically developed definition for the documentary film at this early stage , the directors of the time proceeded according to their own taste. A documentary film made at the time was made under different, often much more difficult conditions than a TV documentary produced today. Fanck's films were never documentaries by today's definition. Films like Im Kampf mit dem Berge are technically perfect even from today's perspective.

Fanck and team members such as Hans Schneeberger and Hannes Schneider , later Gustav Diessl , Sepp Rist , Harry R. Sokal and Ernst Udet , faced some highly decorated former World War II soldiers, whose experiences and telling of decisive experiences at the front on the battlefields , in trenches and in the Air combat was shaped. Fanck couldn't contribute anything due to a lack of personal experience at the front, a problem for the director that he tried to counter with harshness and masculinity on set. The team members who had survived the First World War at the front were used to taking high risks, going to the limit and sometimes even beyond. They were looking for the thrill, they really needed the adrenaline rush .

Fanck acquired its mountain and ski movies, the cinema myths for a humiliated sentient Nation on the Move, which after the First World War , November Revolution and the Treaty of Versailles in the young and very fragile democracy of the Weimar period after epics longing and romance, a sizable proportion also for a world unknown to them and seemingly inaccessible, that of the high mountains . At the time when Fanck's first successful mountain films were made, the National Socialists were of no importance, but far-right forces had already made themselves clearly noticeable (see Kapp Putsch ).

"These films [" Wunder des Schneeschuhs "," Im Kampf mit dem Berge "," Fuchsjagd im Engadin "] were extraordinary in that they captured the most grandiose aspects of nature at a time when the German screen in general offered nothing but studio- made scenery. "

Fanck's mountain and ski films were the result of expeditions to often undeveloped areas, and were shot under the most difficult conditions and at risk of death. The film The Miracle of the Snowshoe , filmed on Feldberg in the Black Forest , for which Fanck had 5 quintals heavy film equipment including a voluminous Ernemann slow-motion camera pulled up the mountain by sled, premiered in the late summer of 1920 as the world's first ski film in Berlin's Scala in front of around three thousand viewers and members of the government also became very successful internationally.

Fanck was one of the first to film with the Ernemann slow motion camera, the first to do sports in the high mountains. The film The Wonder of the Snowshoe , which ran on Broadway for several years and was seen by around 10 million people, founded the genre of ski and sports films. Reich President Friedrich Ebert is said to have expressed his enthusiasm for the slow-motion recordings contained therein. Marcellus Schiffer , one of the viewers, described Fanck's film as “wonderfully healthy!” The contemporary film critic Lotte Eisner judged Fanck's mountain films : “Visions of mountain masses, of snow slopes that blow away in the storm, the fugues that roar with the force of their montage gigantic orchestration ”.

At the same time, the film marked a departure from the previously primarily documentary and independent work of Fanck. Small game activities were integrated from 1921/22, the public taste had to be taken into account for economic reasons. In essence, Fanck did not want to go beyond a realistic representation of nature or mountains; it was primarily about authenticity.

Doubles , trained actors or studio recordings were frowned upon at Fanck at first, but the latter came up frequently later, although the plot of the game mostly remained a weak point of Fanck.

"Fanck's early works, most of which he produced himself, were primarily visually fascinating, semi-documentary series of images in which the storyline was of secondary importance."

Arnold Fanck worked from 1923 with Luis Trenker in Der Berg des Schicksals and from 1925 with Leni Riefenstahl in Der heilige Berg , both of whom he discovered for their roles as actors and thus paved their entry into the film industry.

“[...] There were no mountain films at all, and back then there weren't any such moving images. The clouds, for example, lived and moved, something that didn't exist back then. Fanck was a pioneer there. And the slow-motion shots and above all the lighting, the backlight and the image settings, it was all artistic. So that was far - far ahead of its time. You noticed immediately, without understanding much about the film, that it was a very special - very special art form that I saw there for the first time on the canvas wall (sic!). "

Both Trenker and Riefenstahl were sponsored by Fanck; Fanck and Trenker are said to have been largely eroticized by Leni Riefenstahl. The fictional plot of the film The Holy Mountain reflected what was actually happening on the set : a woman stands between two men. At times there were around five men on the set: director and screenwriter Fanck, cameramen Sepp Allgeier and Hans Schneeberger , co-producer Harry R. Sokal , actor Luis Trenker. The Innsbruck-based banker Sokal, partly of Jewish descent, had been a sponsor and financier of Riefenstahl's career since 1923 and at the same time a staunch admirer. Sokal initially had a 25 percent share in the production of the script for Der Heilige Berg , written by Fanck for Riefenstahl , until he withdrew from the set because of the male competition for Riefenstahl. Without Sokal, a large part of Fanck's films would probably not have been possible. The UFA's entry allowed a much higher budget and ended the financial bottlenecks that had prevailed up until then. She offered Fanck 300,000 Reichsmarks for a new mountain film on the premise that it had to have a plot. This is how The Holy Mountain was created on the basis of a book by Gustav Renker .

Leni Riefenstahl maneuvered herself through Fanck's mountain films into the role of the “ Reichsgletscherspalte ”, a contemporary and extremely suggestive attribution , also due to the men’s interest in copulation on the set . This was a term from which the so titled " Reichswasserleiche " was later derived for another actress. As a woman, Riefenstahl first had to assert himself in the male domain of mountain film and managed to do so - through enormous ambition, iron will, athletic talent and the targeted use of eroticism and sex. In her role in Fanck's mountain films as well as on the set, Leni Riefenstahl embodied the demonized, but also modernizing element, and turned out to be a source of conflict. It reflected the insecurity of men in the interwar period, who were confronted with a changing image of women and a changed relationship between the sexes.

Was it a coincidence that Fanck's film The Holy Mountain was made so soon after Thomas Mann's educational novel The Magic Mountain was published? The parallels between this literary work and Fanck's personal alpine awakening story are obvious and could have inspired Fanck.

Fanck developed trend-setting films for Universum Film AG (UFA), Althoff-Amboss-Film AG (AAFA-Film) and Deutsche Universal-Film AG .

“Fanck's role as the first plein air painter , as the first luminist in German film, was undisputed. Fanck was a pioneer (and also a fetishist ) of outdoor filming. He opened the gap to the ( silent ) film that was groping in the tightness , which for years no one except himself was able to fulfill. "

In his films , Fanck glorifies and stylizes the experience of nature, the mountains and sports. Fanck's mountain films aestheticized and mystified nature, celebrated a cult of the body, breathed the spirit of the life reform movement , but not the demon of fascist ideology. Contemporary film critics repeatedly made connections between Fanck's mountain films and Fidus . "Drum up, German film, to the holy mountain of the rebirth of yourself and the German people!"

Film scholars identify an ideologization , functionalization and remythologization of nature in Fanck's early work, which suggests its controllability by humans and characterizes natural forces as “just”.

An “anti-civilizing spirit” woes through Fanck's films, the “untouched nature” appears “as a refuge for those who flee from society [...]”. German mountain films correspond to an “ anthology of proto - Nazi feelings”, are “reactionary fantasies” that are not only fed from “anti-modern convictions” but also encourage them.

Fanck attributes a quasi-religious meaning and ethical dignity to mountaineering . Like the romanticism of Richard Wagner or the later fascist doctrine, The Holy Mountain mystifies the mortality of the mountaineer and refines or exalts his self-sacrifice. The film suggests a Christian vision of death as a means of redemption and (over) draws the futility of the premature death of two protagonists as a creed for friendship and loyalty . The film was dedicated to Fanck's deceased friend, the mountaineer Hans Eduard Rohde (1890–1915).

In 1925 Fanck published a pioneering large-format illustrated book, which subsequently strongly promoted skiing: The miracle of snowshoeing - a system of correct skiing and its use in alpine cross-country skiing . With 242 single images and 1,100 cinematographic series images by Sepp Allgeier and the Arlberg ski technique propagated by Hannes Schneider , the basic knowledge of skiing as the simplest thing in the world was conveyed. Fanck invested a lot of time in this illustrated book in order to select suitable sequences from a large amount of Allgeier's film material, which could illustrate the motion sequences while skiing.

Fanck became internationally known from 1928 with his probably most successful mountain drama The White Hell from Piz Palü , for whose film producer Harry R. Sokal had insisted on engaging Georg Wilhelm Pabst as co-director to lead the actors. The support from GW Pabst seemed important to Sokal because Fanck's own ability to lead his actors should have been very limited. In contrast, he is certified cinematic virtuosity.

With the clear aim of achieving dramatic and believable shots, Fanck did not spare his actors during filming; he was mercilessly perfectionist . For his film The White Hell from Piz Palü , he had a wall of snow blown off above the actress Leni Riefenstahl in order to give the recordings the desired drama. This expressed a real hatred of Fanck because of the demands that Fanck put on his actors, which went beyond the performance limits. Overall, however, it was at times a love-hate relationship that both connected and divided Fanck and Riefenstahl.

Fanck is described as tough on himself and others, as success-oriented, egomaniacal , vain and sadistic . He couldn't take criticism. In these characterizing attributions, he is probably not fundamentally different from Leni Riefenstahl.

In 1928 Fanck filmed the II. Olympic Winter Games ( The White Stadium ), which took place in St. Moritz .

The Cinematography changed, the talkies came in. In his later films, Fanck had to fall back on trained actors, some of whom were disqualified as " salon Tyroleans " by his team of experienced skiers and mountaineers .

Fanck's first sound film was Storms over Mont Blanc , in whose plot he let man-made technology triumph over the forces of nature. At the same time, he integrated clearly recognizable sexual allusions to the Leni Riefenstahl he coveted into the film.

“But there are many who accuse Fanck of mixing stories of small human fates into the big pictures of his mountain world. This criticism belongs to those who contradict themselves. Can size be represented differently than measured by the relative smallness of everyday human life? Photo sheets of beautiful landscape backgrounds have already been photographed by others in front of Fanck. But its mountains become dramatic because they are part of a game. Fanck directs glaciers and avalanches and storms over the Montblanc. Elements of nature become dramatic elements, living creatures, because they encounter living beings. The rock looks threatening because it threatens someone and is seen through the eyes of the threatened. The blizzard becomes a terrible fate because it interferes with the fate of people. He becomes an antagonist in battle because he opposes the intention, the wild will of a person. This is how nature in Dr. Fanck's films have a face. And that is where art begins. "

From December 1931, The White Rush ran - new wonders of the snowshoe in the movie theaters. This ski film, reveling with relish in a clearly expressionistic form, is still able to inspire freestylers and snowboarders today , while Klaus Mann perceived it in January 1932 as an "amazingly bad and monotonous snow and ski film with the incompatible (sic!) Lousy Leni Riefenstahl".

In 1932, the bilingual German-English Universal Film Lexicon published by Frank Arnau said: "Arnold Fanck is the author and director of the most wonderful high-mountain films that have ever been made". Leni Riefenstahl, who was working on her first film as a director at the time, handed over the film Das Blaue Licht , which she had initially edited herself, to Fanck because she was very dissatisfied with the result. It was only after Fanck had cut it and saved the work that Riefenstahl expressed satisfaction with the way she wrote Béla Balázs .

In 1932 Fanck traveled to Universal Studios in Hollywood at the personal invitation of Carl Laemmle . Laemmle, who was of German-Jewish descent, had drew all the wrath of the Nazis two years earlier as the producer of the two-time Oscar- winning film adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque's anti-war novel In the West Nothing New .

In Hollywood Fanck sat next to Marlene Dietrich at a festival held in his honor with many Hollywood stars , with whom, however, he found no starting point for a conversation; The interests and horizons of experience were too different.

The result of the consultations between Laemmle and Fanck was a budget of 1 million Reichsmarks ; it formed the Universal Dr. Fanck Greenland expedition for the film SOS Eisberg to be made off Greenland . Fanck negotiated the protectorate of the polar explorer Knud Rasmussen because Greenland was a territory closed to foreigners to protect the Eskimos .

At double-digit minus degrees, Fanck forced the actors to go to calving icebergs and into the waters of the Arctic Ocean ; the film team narrowly escaped death. Aviator ace Ernst Udet contributed the recordings from the air , a "box office magnet". After the rigors of filming and despite all the (real) drama of the film, it was not quite enough for Universal Studios from an American perspective. When this kitschy changed the end of the finished film without Fanck's consent in the manner of Hollywood, he canceled his already agreed option for three more films for Universal and thus gave himself a Hollywood career within reach.

During the Games of the X Olympiad 1932 in Los Angeles, two German mountaineers, the brothers Franz Xaver and Toni Schmid , the International Olympic Committee (IOC) with the olympique Prix d'alpinisme of the ascent of the Matterhorn - north face appreciated. For the film genre of mountain films , this meant maximum attention from an euphoric audience immediately before the transfer of power to the National Socialists .

Nazi era

During the National Socialist era , Fanck refused to work with the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda , led by Joseph Goebbels , and he also refused to join the NSDAP . I.a. This is probably due to the fact that, despite his expertise as a world-famous ski and sports film pioneer, he was neither involved in the films about the Olympic Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen nor the Olympic Summer Games in Berlin in 1936 . Another reason was Leni Riefenstahl's offensive for Hitler's favor , through which she was commissioned directly by the “ Führer ” from 1933 , past Goebbels. In contrast, Goebbels sponsored Luis Trenker's mountain films, which he probably did with the documentation of the XI Games. Wanted to commission the 1936 Olympics in Berlin before Hitler had entrusted Leni Riefenstahl with it.

Several of the cameramen from Fanck's Freiburg school were later part of Leni Riefenstahl's film teams . This was based exclusively on the expertise of Fanck's cameramen in open-air cinematography. Exactly this experience was in demand during the Nazi era for the realization of large documentary film projects. Riefenstahl benefited enormously from the creativity and knowledge of the experienced camera pioneers, with whom she had come into contact both artistically and through numerous affairs on the set and who had skimmed off their know-how, as she herself confirmed in an interview in the early 1970s.

“He [Arnold Fanck] taught me that you have to photograph everything equally well: people, animals, clouds, water, ice ... Every time you take a picture, the aim is to go beyond mediocrity, to get away from the routine and do everything with you if possible to see a new look. [...] "

Those films by Riefenstahl for the Nazi regime, which she vehemently labeled as documentaries throughout her life, differed in one essential point from the original approach of their teacher Fanck: they were staged from A – Z. However, the tendency to heroize and glorify the protagonists is similar ; at Fanck it was the skiers and mountaineers, when Riefenstahl the aesthetically idealized Olympians , the mass choreography of marching men in uniform on the Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg and their by bottom view excessive, and as an ideal type defined "leaders", she continued by all means the former cinema in the limelight . Fanck presented his mountaineers and skiers as well as the mountain world and nature as ideal-typical or iconographic . However, not the untouched nature, but the nature touched by people.

The National Socialists hijacked - like many others - the mountain film genre, which they considered suitable for appropriating it for the Nazi ideology. The seemingly heroic sport of mountaineering, the unbroken will to take on the mountain, the comradeship of the rope teams that was conjured up to the death, and ultimately the conquering of the mountain, all fit the fight-and-victory ideology. The mountain film now turned increasingly brown, not least because of the specifications and censorship by Goebbels. Fanck was sidelined, from which Riefenstahl and Trenker benefited.

On June 24, 1933, Joseph Goebbels noted in his diary: “[…] I'm going to visit Dr. Fanck. Little Lantschner there. A nice guy and a real Nazi. Greenland film. Will be a grandiose work. [...] "

Fanck began work on his film The Eternal Dream in December 1933 , which not only told of French heroes on the French mountains , but also dealt with the " hereditary enemy " then called , but also with Jewish people through the Cine Alliance ( Arnold Pressburger and Gregor Rabinowitsch ) Producers had. The National Socialists approved neither the subject nor the producer; Fanck did not behave opportunistically and was not influenced by Nazi ideology .

From July 30, 1934, everyone in the Reichsfilmkammer (RFK) who wanted to work full-time in the film business had to be a member. The prerequisite for membership was, in addition to the “ Aryan certificate ”, an examination of whether the applicant had violated the Nazi ideology in the past.

In 1936 Fanck joined the National Socialist People's Welfare (NSV).

In the absence of orders, which were increasingly only awarded by the Nazi Propaganda Ministry , Fanck ran into economic difficulties that he was not able to overcome until 1936 with an order from the Japanese Ministry of Culture . His childhood friend Friedrich Wilhelm Hack , an arms dealer and interpreter who worked in the diplomatic service in Japan and was a board member of the German-Japanese Society (DJG) from February 1935, brokered this well-paid contract . For this purpose Fanck and Hack operated a joint film company for cultural films. The Japanese paid all of the production costs, providing around ten times the cost of an average Japanese film.

With The Daughter of the Samurai (1936) and other “ cultural films ”, Fanck tried, in the absence of non-governmental commissions, to continue working on an artistic and cultural basis and took Richard Angst and Walter Riml with him. However, he had to accept the influence and censorship of the Nazi propaganda ministry. Fanck's friend and business partner Hack prepared the Anti-Comintern Pact ; Goebbels is said to have had a strong interest in the film project in Japan, a prerequisite for its approval, but was far less impressed with the finished film than the Japanese.

Fanck's film Ein Robinson - The Diary of a Sailor (1938/39) for Bavaria Filmkunst , which was filmed on the Juan Fernández Islands , Tierra del Fuego and in Patagonia and made by Fanck , finally fell completely out of favor with Minister Goebbels . Fanck filmed historical material that was to be transformed into the present (then). However, Goebbels saw in the reclusive Robinson an anti-social figure who opposed the national community propagated by the Nazi system , removed Fanck final control over the film and had the studio rework Fanck's film material into a profane propaganda film for the Navy . Sepp Allgeier was also involved in this in the studio .

1938 succeeded a German and an Austrian roped the ascent of the Eiger - North Face . The National Socialists burst into jubilation at the associated symbolism in the year of the so-called “ Anschluss ” of Austria . The alpinist and SS man Heinrich Harrer , who was involved in this success, commented after the reception with Adolf Hitler : "We have climbed the north face of the Eiger over the summit to our guide." Such a pathetic statement passed on both mountaineering and (indirectly ) the genre mountain film to the National Socialist leader cult.

“And then in '39 my entire career was suddenly cut short. […] I was sidelined […] and could never get my really big projects back. "

Fanck joined the NSDAP very late - possibly too late for a conceivable success in the Third Reich - only in April 1941 (he was initially listed as a candidate for membership), a step that he did not like and that is probably seen in the context of film projects which Leni Riefenstahl offered or mediated to him. This is a belated attempt to ingratiate Fanck against the Nazi state in order to be able to continue making films.

In April 1941 Fanck was received by the General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital (GBI), Albert Speer , in his Berlin office building at Pariser Platz 4 , through Riefenstahl's mediation . The latter commissioned him to edit all of the GBI's construction films that concern the capital , including films about the construction of bunkers ( Organization Todt ) and the repair of bomb damage .

Speer guided Fanck through the New Reich Chancellery on November 23, 1941 , which Fanck then filmed inside and out. Fanck shot in the film studio of the Reichstag building and recorded Speer's models of the “ World Capital Germania ” project, which was particularly dear to Hitler, including the monstrously projected Great Hall .

Since Speer informed Leni Riefenstahl in writing immediately after these two meetings in April and November 1941, one can assume that Fanck's commissioning was initiated by Speer on the part of Riefenstahl.

When the property with Fanck's villa in Berlin-Nikolassee was to be transferred to the International Forestry Institute in the course of the decree on the redesign of the Reich capital Berlin of November 5, 1937 , it was Speer himself who temporarily prevented this on the grounds that it would take place during the execution To want to give time to Fanck's orders for the GBI so that Fanck can build or look for another place to stay. Speer also informed Riefenstahl about this in writing. Speer offered Fanck in writing to fall back on "Jewish villas" bought "by us" (through the GBI). It is possible that the villa in which Fanck lived (affected properties at Am Sandwerder 33 to 41 ) would have been demolished for new Nazi buildings. The course of the war prevented that.

Despite Fanck's party affiliation, the planned but not completed film documentary about the "World Capital Germania", the documentary about the sculptors Josef Thorak (1943) and Arno Breker (1944) and about the Atlantic Wall , made together with Hans Cürlis , were no longer completed produced independently by Fanck, but by Riefenstahl-Film GmbH , Kulturfilm-Institut GmbH and UFA-Sonderproduktion GmbH . Thematically, none of these film projects were related to Fanck's actual focus on mountain films, but the short films on Breker and Thorak were related to art and thus to culture.

Fanck's last commissions during the Second World War were partly carried out under the responsibility of his former student Riefenstahl. In any case, he was paid by Riefenstahl-Film GmbH from 1942 to 1944 like an employee with a fixed monthly salary.

In Carl Zuckmayer's secret report, published only in 2002, which he wrote in 1943/44 for the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), about successful German actors, directors, publishers and journalists from the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich, Arnold Fanck is mentioned in the context of characterizing Leni Riefenstahl as a successful film director, but without any personal or political judgment.

post war period

In 1946 the Fanck family moved to the former Bismarck'schen Lilienhof near Ihringen am Kaiserstuhl , which at that time was owned by Fanck's nephew and former film actor, the doctorate architect Ernst Petersen . In 1935 he married Elisabeth Henkel, daughter of the Düsseldorf industrial family of the Persil inventor Hugo Henkel . In 1935/36 Ernst Petersen was among other things the draftsman of the plans for the Villa Riefenstahl and in 1937 had received the Grand State Prize of the Prussian Academy of the Arts for architects .

Two of Fanck's films made during the Nazi era were initially banned by the military governments of the occupying powers after the Second World War : The daughter of the samurai struck the Allies negatively because of the German-Japanese connection, and Ein Robinson - The Diary of a Sailor was used as a Nazi propaganda classified for the German navy.

In contrast to Siegfried Kracauer's fundamental criticism, published retrospectively in 1947, which sought to recognize a continuity in the cinematic works of Fanck, Trenker and Riefenstahl, a more detailed analysis between these three filmmakers shows more differences than analogies. Trenker and Riefenstahl based thematically and technically on Fanck's work; they had both emerged as actors from Fanck's mountain films and had taken the tools provided by Fanck and his operators as a foundation for their own directorial work, even luring some of these cameramen. The contemporary reception, however, showed just as significant differences as the career progression of the three film directors during the Nazi era, because only Fanck's career broke off in 1939 after it had ceased to be linear in 1933. In contrast, Trenker's and especially Riefenstahl's careers picked up speed rapidly after January 30, 1933, while the mountain film took a dubious turn at the same time. Hitler sponsored Riefenstahl with almost inexhaustible budgets, Goebbels sponsored Trenker. Fanck did not have a comparable comprehensive protection. In essence, Kracauer refuted his genealogy construction Fanck – Trenker – Riefenstahl himself in 1947 by postulating with regard to Fanck's work: "In the documentary genre, these films achieve incomparable". As a result, he ultimately confirmed clearly noticeable differences to Trenker and Riefenstahl. From an ideological point of view, Fanck was certainly not too far removed from certain ethnic and anti-Semitic tendencies, as revealed in passages of his diaries and letters.

Fanck tried to regain a professional foothold. He was hoping for support from the city of Freiburg im Breisgau to re-establish his former Berg- und Sport-Film GmbH , but this did not materialize. He re-founded it with a license from the French military government , but it did not get into productions because Fanck's plans did not meet with interest.

Because of his NSDAP membership, Arnold Fanck was classified as a “ fellow traveler ” during the “ denazification ” on the part of the State Commissioner for Political Cleansing on February 7, 1948 ; he was not charged with any offense. On the question of his professional activity or his income per year between 1933 and 1945, Fanck noted in the questionnaire for his hearing for the years 1934, 1937 and 1939 to 1941: "Without commitment".

Due to the restitution of Jewish property expropriated during the Nazi era on the basis of the US Military Government Act No. 59 , Fanck had to rent the Villa Am Sandwerder 39 in Berlin-Nikolassee, which he rented in 1934 and acquired in 1939 (Nikolassee was in the US-occupied part of West Berlins ) to the former Jewish owner family of Bruno Mendel in accordance with the decision of the Reparation Chamber of the Berlin Regional Court . For their use he had to raise a rent for the period from 1939 to around 1953. Arnold Fanck was awarded a repayment fee and had to pay off the creditors of a mortgage from it .

Fanck received no more commissions, moved to his very old mother in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1948, wrote his autobiography and became impoverished. The geologist and world-famous film director now worked as a forest worker in the Black Forest . In the 1950s, non-documentary homeland films with shallow storylines were the new trend; the grandiose mountains initially faded into the background. Harry R. Sokal funded and co-funded Fanck's smaller productions in the 1950s.

With the screening of his film The White Rush at the Biennale in Cortina d'Ampezzo in 1954 and The Eternal Dream at the Mountain Film Festival in Trento (1957), Arnold Fanck experienced another phase of artistic recognition. However, he was only able to survive economically by transferring the rights to his films to a friend until his financial situation improved through the resumption of performances of his works.

“And what was the best part: my time as a skier and my alpine tours. Those were the best times of my life. "

Shortly before his death, Fanck felt hard hit by a regional decision that his film SOS Eisberg was not suitable for showing in front of young people. Fanck died in 1974 after a long illness in a Freiburg hospital. He was buried in the family grave of the main cemetery in Freiburg im Breisgau. Parts of his estate are kept in the Federal Archives , the Munich Film Museum and in the archives of his grandson Matthias Fanck .

“Fanck was a great romantic. And it was his great art to bring the majesty of the mountains, the beauty of the mountains, and the danger of the mountains to a broad audience in black and white. A stimulus for people to enter this great world. With Fanck, the mountain has acquired a completely new attraction. The audience saw for the first time how these clouds move over the mountains at Fanck films, they saw the steepness, they saw avalanches, they felt the frost ... "

Film technology

Allgeier and Fanck were constantly developing new camera technologies, "unleashing" the camera by mounting it on the front of the ski . They cut a wide variety of black masks for focusing the lenses because there was no zoom function yet. In this way, Allgeier and Fanck became important sources of ideas for innovative camera work, which half a century later, for example, Willy Bogner ( fire and ice , ski action scenes in various James Bond films), Leo Dickinson and Reinhold Messner orientated themselves.

"The Fanck films were of course a role model for everyone who works in the field."

Filmography

Triggered by the unprecedented success of Fanck's first ski films during the 1920s, skiing in particular developed into a popular sport, and mountaineering also became popular. This established or stimulated both alpine tourism and an entire industrial sector.

Well-known composers were hired for Fanck's films, for example Paul Hindemith under the pseudonym Paul Moreno, who composed the first film music created for a full-length film for Fanck's film Im Kampf mit dem Berge . Subsequently, other well-known composers such as Giuseppe Becce , Paul Dessau , Werner Richard Heymann and Edmund Meisel worked . As the first Japanese composer, Yamada Kōsaku ( Japanese 山田 耕 筰 ) tried to harmoniously unite Far Eastern and Western musical traditions in his composition for Fanck's film The Daughter of the Samurai .

Helmar Lerski worked on Fanck's mountain films as a cameraman ( Der Heilige Berg ) and as co-scriptwriters Ladislaus Vajda ( The White Hell from Piz Palü ) and Friedrich Wolf ( SOS Eisberg ), the latter under a pseudonym.

Main work

- 1920: The miracle of the snowshoe

- 1921: In the fight with the mountains , 1st part: In storm and ice - an alpine symphony in pictures

- 1922: The wonder of the snowshoe , Part 2: A fox hunt on skis through the Engadine

- 1924: The Mount of Fate

- 1925: The white art

- 1926: The Holy Mountain

- 1927: The big leap

- 1928: The white stadium

- 1929: The white hell of Piz Palü ; USA (1930): White Hell of Pitz Palu , D (1935): The white hell of Piz Palü (audio version, abbreviated)

- 1930: Storms over Mont Blanc

- 1931: The white intoxication - new wonders of the snowshoe

- 1933: SOS Iceberg ; USA (1933): SOS Iceberg

- 1934: The Eternal Dream , also: The King of Montblanc ; France (1935): Rêve éternel , also: Le roi de Montblanc

- 1937: The Samurai's Daughter ; Japan (1937): 新 し き 土 (Atarashiki Tsuchi = New Earth)

- 1940: A Robinson - A Sailor's Diary

producer

( Berg- und Sport-Film GmbH , Freiburg im Breisgau)

- 1920: The masters of water

- 1921: With the Jungfrau Railway to the regions of eternal ice

- 1921: Jiu-Jitsu - the invisible weapon

- 1921: The great Dempsey - Carpentier boxing match

- 1921: Moritz, the dreamer - How Moritz imagines the creation of the world

- 1922: The dying city

- 1922: The German fighting games in 1922

- 1922: A great ride - a sailing film and what surgeon Huckebein experienced when it was shot

- 1922: Chufu

- 1922: Ali-Baba and the 40 robbers

- 1922: Earth - Mars football competition

- 1922: Pömperli's fight with the snowshoe

- 1923: $ 1,000 reward - 10,000 mark reward

- 1923: Saving Franz's life - an experience among the savages

- 1923: The heart of man

- 1924: The Maloja cloud phenomenon

- 1924: The coveted Lotte or "What delightful little feet"

- 1924: The Dead Wolf

- 1925: Rowing

- 1926: South Tyrol - an outpost of German culture

- 1926: Winter sports in the Black Forest

- 1927: Winter sports in the Black Forest

Short films

- 1932/34: The whale II. Processing (?)

- 1932/34: The seals

- 1931/35: Top performance in skiing

- 1935: Training for ski filming

- 1938: Imperial buildings in the Far East

- 1936/38: Winter trip through southern Manchuria

- 1939: Little Hans

- 1939: On new paths

- 1936/40: Rice and wood in the land of the Mikado

- 1940: From Patagonia to Tierra del Fuego

- 1936/41: Spring in Japan

- 1936/41: Japan's sacred volcano

- 1943: Joseph Thorak - workshop and factory

- 1936/44: Pictures of Japan's coasts

- 1944: Arno Breker - Hard times, strong art

- 1944: Atlantic Wall

- 1944: New buildings in the Reich capital (?)

- 1944: The Führer builds his capital (?)

- 1956: Tetje and Fiedje (how they once learned to ski)

- 1956: Tetje and Fiedje (how they once wanted to catch a vixen)

- 1956: Tetje and Fiedje (how they once almost got their smucky Deers)

- 1956: Tetje and Fiedje (how they once got a pair of skis)

Cooperation

- 1913: 4628 meters high on skis ascent of Monte Rosa

- 1927: Milak, the Greenland hunter

- 1928: The battle for the Matterhorn

- 1928: Dolomite majesties

- 1929: Om mani padme hum - Of distant people and gods

- 1930: The three holy wells - Symphony of the Mountains

- 1932: Fleeing shadows

- 1932: Adventure in the Engadine

- 1934: North Pole - Ahoy!

- 1936: The wilderness dies

- 1956: Small tent and great love or The current flows on - two in a sleeping bag

Unrealized projects

- 1927: A winter fairy tale, solstice

- 1928: Sarka

- 1930: The black cat, Il Monte Santo

- 1932: And I also have no money ... somersault into luck

- 1934: Badinga, the king of the gorillas

- 1934: The avalanche

- 1935: The sinking of the Sisto. The night of horror of December 18, 1934

- 1939: Genghis Khan

- 1944: Reich Chancellery

- 1944: New buildings in the Reich capital

- 1944: Carrara marble

- 1944: Furniture in the German workshops in Munich

- 1944: plywood

- 1954: champagne

- 1954: Rebel hands - Tilman Riemenschneider

Compilation films

- 1941: Fight for the mountain - a mountain tour 20 years ago

- 1952: Carnival in white

- 1966: The white intoxication - then and now; The history of skiing from the very beginning

Remakes

- 1950 hair dryer

Awards and honors

- 1954: Prize of the XXVII Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d'Arte in Cortina d'Ampezzo for The White Intoxication

- 1957: Great gold medal at the 6th Festival Internationale Film della Montagna e dell'Esploratione Trento

- 1958: Certificate from the German Cultural Association Urania Berlin e. V. on the occasion of the 8th International Film Festival in Berlin in 1958

- 1963: Mannheim film ducat on the occasion of the XII. International Film Week in Mannheim

- 1964: Film tape in gold for many years of excellent work in German film

- In Freiburg-Haslach (garden city) a street was named after Arnold Fanck, which branches off from Sepp-Allgeier-Straße . For political reasons, however, the latter was renamed Else-Wagner-Straße in 2020 by resolution of the city council .

Criticism (excerpt)

- Christian Rapp : The mountain film genre could “only develop in a socio-cultural environment” “that was conditioned to solemn pathos and was able to unconditionally follow an intuitively acting individual. Not only the distance from life of the landscape, especially the belief in fate of those exposed ”would have“ contributed significantly to the constitution of the genre ”.

- Film critic Siegfried Kracauer , who had worked for the renowned Frankfurter Zeitung , therefore saw Fanck as a herald of the “message of the mountains”, which was “the creed of many Germans”, “with the sublime feeling of imitating Prometheus ”. According to Kracauer, this “heroic idealism” originated “in a mentality related to the Nazis”. "Immaturity and mountain enthusiasm fell into one". [...] In addition, "the idolatry of glaciers and rocks is symptomatic of an anti-rationalism that the Nazis could exploit". On the other hand, he stated: "In the documentary genre, these films [Fancks] achieve something incomparable".

- Essayist Michael Rutschky draws the tongue-in-cheek conclusion based on Kracauer's criticism of Fanck's mountain films: “Mountains are fascist”.

- For Stefan König , the co-curator of the exhibition 100 Years of Mountain Film. Drama, trick and adventure is the mountain film "as a genre, pardon me, too insignificant to ever have had enough power to change social circumstances." However, it is "full [...] with national symbols", so that one should consider whether the mountain film “has made and is utilizing political systems. It is necessary to discuss what contribution the genre may have made to building a system of inhuman [...] "

Publications (excerpt)

- Arnold Fanck: In the intoxication of movement . Franz Hanfstaengl, Munich approx. 1924 OCLC 26586088

- another. with Sepp Allgeier and Hannes Schneider : The miracle of snowshoeing - a system of correct skiing and its use in alpine cross-country skiing. With 242 individual images and 1100 cinematographic series images . Brothers Enoch, Hamburg 1925 OCLC 257750955

- Arnold Fanck: The echo from the holy mountain . Max Lichtwitz, Berlin approx. 1926 OCLC 858795680

- alternatively with Sepp Allgeier, Gyula Arató, Ernst Wilhelm Baader , Hans Schneeberger : jumping, cross-country skiing . Brothers Enoch, Hamburg 1926 OCLC 72454719

- ders .: The seamless deformation of fossils through tectonic pressure and their influence on the determination of species. Observed and worked on the pelecypods of the St. Gallen sea molasses . University of Zurich, Inaugural dissertation, 1929. Gebr. Fretz AG, Zurich 1929 OCLC 1039050987

- ders .: The fight with the mountains - with 60 pictures . Hobbing, Berlin 1931 OCLC 1070580436

- another. with Sepp Allgeier and Hannes Schneider: Les merveilles du ski . Fasquelle éditeurs, Paris 1931 OCLC 10252563

- ders .: Storms over the Montblanc - A picture book based on the film of the same name . Concordia, Basel 1931 OCLC 6297353

- ders .: The skier's picture book. 284 cinematographic images from skiing with explanations and an introduction to a new movement photography . Brothers Enoch, Hamburg 1932 OCLC 1069803554

- ders .: Storms over the Montblanc - A picture book based on the film of the same name . Rudolf Koch, Leipzig 1933 OCLC 475661883

- ders .: SOS iceberg. With Dr. Fanck and Ernst Udet in Greenland - The Greenland expedition of the universal film »SOS Iceberg« . F. Bruckmann, Munich 1933 OCLC 1072470221

- ders .: With the camera in Greenland - Rolleiflex recordings from the Universal Fanck Greenland Expedition in 1932 . W. Heering, Halle (Saale) 1933 OCLC 30678695

- ders .: The Samurai's Daughter - A film that echoes the German press . Self-published by Dr. A. Fanck, Berlin 1938 OCLC 721052513

- ders .: The Samurai's Daughter - A film that echoes the German press . Steiniger, Berlin 1938 OCLC 257555561

- ders .: Memories of the time of our first mountain and sports film company in Freiburg i. Br. [Autumn 1946]. In: ders .: We are rebuilding the Freiburger Berg- und Sportfilm GmbH! Schillinger, Freiburg im Breisgau 1948

- ders .: In memory of the former Freiburg Mountain and Sports Film Society . Freiburg im Breisgau, approx. 1956 OCLC 311385073

- ders .: He directed glaciers, storms and avalanches - a film pioneer tells . Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-4850-1756-6 (autobiography)

- ders .: The white intoxication - a film pioneer tells . German Book Association, Stuttgart / Hamburg / Munich 1973 OCLC 74244650

Literature (excerpt)

- Leni Riefenstahl : Fight in snow and ice (Dr. Arnold Fanck dedicated). Hesse & Becker, Leipzig 1933 OCLC 314568984

- Siegfried Kracauer : From Caligari to Hitler - A Psychological History of the German Film . Dennis Dobson, London / New York City 1947, OCLC 1175509279 ; New edition: Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2019, ISBN 978-0-6911-9134-8

- Klaus Kreimeier : Fanck - Trenker - Riefenstahl. The German mountain film and its consequences . First film seminar of the Deutsche Kinemathek Foundation, April 19 - June 14, 1972. Deutsche Kinemathek Foundation, Berlin 1972 OCLC 247318098

- Valentin Polcuch: Leni Riefenstahl's path led from the Holy Mountain to the triumph of will . In: Die Welt , August 21, 1972

- Herman Weigel : Interview with Arnold Fanck . In: Filmhefte 2 (summer 1976), pp. 3–29

- ders .: About Fanck and his craft . In: Filmhefte 2 (summer 1976), pp. 31-34

- Thomas Jacobs: The mountain film as a homeland film - reflections on a film genre (PDF file; 513 kilobytes). In: Augen-Blick , No. 5 - Heimat, (= Marburger Hefte zur Medienwissenschaft), 1988, pp. 19–30

- Eric Rentschler : High mountains and modernity - a definition of the location of the mountain film . In: Uli Jung, Walter Schatzberg (ed.): Film culture at the time of the Weimar Republic , contributions to an international conference from June 15 to 18, 1989 in Luxembourg. Saur, Munich 1992, ISBN 978-3-598-11042-9 , pp. 195-214

- Béla Balázs : Revisited: The Case of Dr. Fanck. The discovery of nature in German mountain films (= film and criticism 1). Stroemfeld, Basel et al. 1992, ISBN 3-87877-807-4

- Thomas Jacobs: Visual Traditions of Mountain Films - From Fidus to Friedrich or The End of Bourgeois Refugee Movements in Fascism . In: film and criticism 1,1 (1992), special issue Revisited - Der Fall Dr. Fanck , pp. 28-38

- Janine Hansen: Arnold Fanck's "The Samurai's Daughter". National Socialist Propaganda and Japanese Film Policy (= Iaponia Insula Vol. 6). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-447-03973-6 , also: Freie Universität Berlin, revised. Master's thesis, 1996)

- Eric Rentschler: Germany - The Third Reich and the consequences . In: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith (Ed.): History of the International Film . JB Metzler, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-4760-1585-8 , pp. 338-347

- Jan-Christopher Horak (ed.), Gisela Pichler (collaborator): Mountains, light and dream - Dr. Arnold Fanck and the German Mountain Film (for the exhibition in the Munich City Museum / Filmmuseum Munich from November 21, 1997 to February 11, 1998). F. Bruckmann, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7654-3091-9

- Thomas Bogner: On the reconstruction of cinematic representation of nature using the example of a case study - nature in the film "The Holy Mountain" by Dr. Arnold Fanck (PDF file; 6.0 megabytes), dissertation, University of Hamburg, 1999

- Werner Klipfel: From Feldberg to the white hell of Piz Palü - The Freiburg mountain film pioneers Dr. Arnold Fanck and Sepp Allgeier , ed. v. Regional Association Badische Heimat e. V. Booklet accompanying the exhibition in the Städtische Galerie Schwarzes Kloster in Freiburg im Breisgau from November 19, 1999 to January 16, 2000. Schillinger, Freiburg 1999. ISBN 3-8915-5250-5

- Stefan König , Hans-Jürgen Panitz, Michael Wachtler (eds.): 100 Years of Mountain Film - Dramas, Tricks and Adventure (catalog for the exhibition of the same name). Herbig, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-7766-2228-7

- Harald Höbusch: Rescuing German Alpine tradition - Nanga Parbat and its visual afterlife . In: Journal of Sport History , 29 (2002), 1, pp. 49-76

- Friedbert Aspetsberger (ed.): Der BergFilm 1920–1940 . Studienverlag, Innsbruck / Vienna / Bozen 2003, ISBN 978-3-7065-1798-0

- Antje Ehmann, Jeanpaul Goergen, Kay Hoffmann, Uli Jung, Klaus Kreimeier , Martin Loiperdinger , Peter Zimmermann (eds.): History of documentary film in Germany 1895–1945 , 3 vols., Reclam, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-15-030031 -2

- Kay Kirchmann: Scenes of a fight - The cloud images of Dr. Fanck . In: Clouds , ed. v. Lorenz Engell , Bernhard Siegert , Joseph Vogl . Verlag der Bauhaus-Universität , Weimar 2005, pp. 117–129

- Hans-Joachim Bieber: The daughter of the samurai. German-Japanese film productions during the Nazi era. In: Dagmar Bussiek, Simona Göbel (Ed.): Culture, Politics and Public - Festschrift for Jens Flemming (= Kasseler Personalschriften, Vol. 7). Kassel University Press, Kassel 2009, ISBN 978-3-89958-688-6 , pp. 355-377

- David Benjamin Brückel: Back to the Future - On the discussion of the home phenomenon in German-language film using the example of Edgar Reitz's film novel Heimat (PDF file; 17.3 megabytes). Master's thesis, University of Vienna , Vienna 2009, pp. 47–57

- Matthias Fanck: Arnold Fanck. White hell - white intoxication. Mountain films and mountain pictures 1909–1939 . AS Verlag und Buchkonzept, Zurich 2009, ISBN 978-3-909111-66-4

- Kevin J. Harty: Arnold Fanck's 1926 "The Holy Mountain" and the Nazi quest for the holy grail . In: Georgiana Donavin and Anita Obermeier (eds.): Romance and rhetoric - Essays in hour of Dhira B. Mahoney (= disputatio, 19). Brepols, Turnhout 2010, ISBN 978-2-5035-3149-6 , pp. 223-233

- Ingeborg Majer-O'Sickey: The cult of the cold and the gendered body in mountain films . In: Jaimey Fisher (Ed.): Spatial turns - Space, place, and mobility in German literary and visual culture (= Amsterdam contributions to newer German studies , 75). Editions Rodopi, Amsterdam, New York 2010, ISBN 978-9-0420-3001-5 , pp. 363-380

- Annika Wolfsteiner: Der Bergfilm - diachronic analysis of a genre (PDF file; 526 kilobytes), Master's thesis, University of Vienna, Vienna 2012

- Dorit Müller: To the South Pole and to Greenland - space and knowledge in polar fictions by Georg Heym, Alfred Döblin and Arnold Fanck . In: Orts-Wechsel - real, imagined and virtual knowledge spaces (= Trier Contributions to the Historical Cultural Studies , 10), ed. v. Ulrich Port and Martin Przybilski. Reichert, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-9549-0018-3 , pp. 97-115

- Qinna Shen: Beyond Alterity - German Encounters with Modern East Asia . Berghahn Books, New York City 2014, ISBN 978-1-78238-360-4

- Marie Elisabeth Becker: Nature in Arnold Fanck's film "The miracle of the snowshoe" , housework, 2015

- Nina Goslar: In search of the lost film - A film score as a landmark - On the reconstruction of Paul Hindemith's film music "In Sturm und Eis / Im Kampf mit dem Berge" for the silent film of the same name by Arnold Fanck (D 1921) In: Hindemith-Jahrbuch ( Annales Hindemith 2015 / XLIV), Vol. 44, ed. v. Hindemith Institute , Frankfurt am Main 2015, ISSN 0172-956X, pp. 67-76

- Nicholas Baer: Natural History: Rethinking the Mountain Film . In: Jörn Ahrens, Paul Fleming, Susanne Martin, Ulrike Vedder: "But if the real is also forgotten, it is therefore not erased" - contributions to the work of Siegfried Kracauer . Springer-Verlag, Berlin 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-13238-5 , pp. 279-305

- Andreas Münzmay: Extension of the feasibility zone - aesthetic-technical modernity concepts of film and score in Arnold Fanck and Paul Hindemith's "In Sturm und Eis" (1921) . In: Spiel (with) the machine , ed. v. Marion Saxer. Transcript-Verlag, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8394-3036-1 , pp. 317-345

Radio feature about Arnold Fanck

- Eva Lauterbach: I was always good friends with the ice - Arnold Fanck, extreme filmmaker, summiteer, brilliant autodidact , SWR 2011, approx. 54:30 min., Broadcast on Deutschlandfunk Kultur, February 23, 2013, 6:05 p.m.

Films about Arnold Fanck

- 1959: Dr. Fanck 70 years old . In: Südwestfunk -Abendschau, March 6, 1959, 8:41 min., On: ardmediathek.de

- 1989: Who was Arnold Fanck? ( North German Broadcasting )

- 1997: Hans-Jürgen Panitz: In Ice and Snow - The Director Arnold Fanck ( Bayerischer Rundfunk )

- 1998: Between white intoxication and the abyss - Arnold Fanck, the extreme director ( Südwestfunk )

- 1999: Who was Arnold Fanck? Director in rock and ice

- 2013: Drama at the summit ( Südwestrundfunk )

- 2018: Ice cold passion - Leni Riefenstahl and Arnold Fanck between Hitler and Hollywood ( arte , ZDF )

Exhibitions (selection)

- November 21, 1997 to February 11, 1998: Mountains, light and dream , Arnold Fanck exhibition in the Munich City Museum / Filmmuseum Munich

- November 19, 1999 to January 16, 2000: From Feldberg to the white hell of Piz Palü - The Freiburg mountain film pioneers Dr. Arnold Fanck and Sepp Allgeier , exhibition of the Badische Heimat eV regional association. V. in the municipal gallery Black Monastery in Freiburg im Breisgau

- October 31, 2001 - April 14, 2002: 100 Years of Mountain Film - Dramas, Tricks and Adventure , Potsdam Film Museum

- October 7th, 2009: Arnold Fanck - mountain film pioneer - directing with glaciers, storms and avalanches , Haus des Gastes, Tegernsee

- October 8, 2009 to March 7, 2010: Exhilaration of movement. Unknown ski impressions by Arnold Fanck , studio exhibition as part of the Tegernsee Mountain Film Festival 2009 , in the Alpine Museum , Munich

Audio

- Kerstin Hilt: The premiere of the film "The White Hell from Piz Palü" , November 15, 1929. In: Zeitzeichen , Südwestrundfunk , November 14, 2019, podcast 14:38 min., On: swr-mediathek.de

Videos (selection)

- Arnold Fanck: Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs ( The Wonders of Skiing ), 1920, 31:32 min., On: youtube.com

- ders .: The cloud phenomenon of Maloja , 1924, 10:21 min., on: youtube.com

- ibid .: The Holy Mountain ( The Holy Mountain ), 1926 1:44:07 hours on. youtube.com

- DERS with. Georg Wilhelm Pabst : The White Hell of Pitz Palu ( The White Hell of Pitz Palu ), 1929, 2:14:23 hours on. youtube.com

- Arnold Fanck: Storms over Mont Blanc ( Storm Over Mont Blanc ), 1930, 1:33:51 hours, on: youtube.com

- ders .: SOS Eisberg ( SOS Iceberg or Iceland ), 1933, 1:26:25 hours, on: youtube.com

- ders .: The Eternal Dream ( The King of Montblanc ), 1934, 2:14:24 hours, on: youtube.com

- ders .: The Samurai's Daughter , 1937, 1:46:14 hours, on: youtube.com

- Dr. Fanck 70 years old . In: Südwestfunk -Abendschau, March 6, 1959, 8:41 min., On: ardmediathek.de

- Hans-Jürgen Panitz: In ice and snow - The director Arnold Fanck , documentary, Bayerischer Rundfunk 1997, 47:26 min., On: youtube.com

Web links

- Literature by and about Arnold Fanck in the catalog of the German National Library

- Arnold Franck in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Arnold Fanck at filmportal.de

- Fanck's films on the Walter Riml homepage (camera)

References and footnotes

- ↑ a b Birth certificate no. 75 from March 9, 1889 at the registry office in Frankenthal (Pfalz) for Arnold Heinrich Fanck, born on March 6, 1889 “in the afternoon at seven and a half o'clock”. The entry contains the different denominations of the parents (father Catholic, mother Protestant); Quoted according to a photographic copy by the City Archives Frankenthal (Pfalz), Dörte Kaufmann, July 21, 2020

- ↑ a b c marriage register entry of the marriage between Fanck and Zaremba on May 20, 1920 in Zurich, signature: VIII.Ba1.:2.168. Marriage register A, Volume II, No. 954, Zurich 1920, p. 491, facsimile of the original document transmitted by the Zurich City Archives, Dr. Nicola Behrens, July 10th, 2020 - This register entry, the data of which is also based on the birth certificates of the bride and groom, contains Fanck's middle name, Arnold Heinrich

- ↑ Fanck, Arnold . In: Deutsche Biographie , on: deutsche-biographie.de

- ↑ Fanck, Arnold . In: City of Frankenthal (Pfalz) , on: frankenthal.de

- ↑ Thomas Kramer (Ed.): Reclam Lexikon des Deutschen Films . Reclam-Verlag, Ditzingen 1995, ISBN 3-15-010410-6 , pp. 51, 67, 76, 88, 93, 109, 125, 297, 421

- ↑ 100 Years of Mountain Film - Dramas, Tricks and Adventure , on: filmmuseum-potsdam.de

- ↑ a b c d e The mountain film - comments and assessments on a controversial genre . In: Filminstitut Hannover , on: geschichte-projekte-hannover.de

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lars-Olav Beier, Hilmar Schmundt: The vertical western (PDF file; 593 kilobytes). In: Der Spiegel , No. 49 (2007), pp. 212–215

- ↑ a b Winfried Lachauer: Skis conquer the Black Forest - The Success Story of Winter Sports , SWR documentary, 89:41 min., First broadcast on January 12, 2018, 8:15 pm

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Alexander Kluy: Visions of mountain masses and snow slopes . In: Die Welt , January 11, 2010, on: welt.de

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Donald G. Daviau : The Artistic Films of Arnold Fanck, the Apostle of Skiing and High-Mountain Climbing . In: Polylogzentrum , on: polylogzentrum.at

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Annette Baumeister: Ice cold passion - Leni Riefenstahl and Arnold Fanck between Hitler and Hollywood . ZDF, arte 2018

- ^ Siegfried Kracauer: From Caligari to Hitler - A Psychological History of the German Film . Dennis Dobson, London / New York City 1947, OCLC 1175509279 and Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 2019, ISBN 978-0-691-19134-8 , pp. 257-258

- ^ Death certificate No. 166 from June 16, 1906 at the registry office Frankenthal (Pfalz) for Christoph Friedrich Fanck; Quoted according to a photographic copy by the City Archives Frankenthal (Pfalz), Dörte Kaufmann, July 21, 2020

- ↑ Christoph Friedrich Fanck was born in Emmendingen on December 4, 1846 , the son of the Grand Ducal Baden track master Mathias Fanck . In Karlsruhe , Christoph Friedrich Fanck completed a commercial and a banking apprenticeship, which he was able to apply for the first time in the Badische Gesellschaft für Zuckerfabrikation in Waghäusel . From 1873 he worked in the Franz & Carl Karcher sugar factory in Frankenthal, which in the same year was converted from a family business to the Frankenthal sugar factory with start-up capital of 1.2 million marks . Since 1868 the company has only been involved in refining the raw material. Due to the broader financial basis, the factory developed into one of the largest sugar refineries in the German Empire in the following years . After the death of the factory owner Philipp Karcher in 1894, Christoph Friedrich Fanck became director of the Frankenthal AG sugar factory . It was the original company of the Südzucker Group . The royal Bavarian government awarded him the title of Royal Commerce Councilor in 1898 because of his services to trade and industry in the Palatinate . In Frankenthal he was a respected personality whose advice was sought. In accordance with his position, he was chauffeured in a stately coach, in front of which two white gray horses were harnessed. After his untimely death at the age of 59 on the morning of June 16, 1906 at 8 a.m., a large number of fellow citizens attended his funeral, which was a long one on the way between the house where he died, his villa at 1 Mahlastrasse, to the cemetery Processional procession formed, which reached from the Speyerer Tor to the cemetery entrance. Along the way from the deceased's villa to the Frankenthal cemetery, all the street lamps were adorned with mourning ribbon; many residents showed their condolences on their houses by wearing a black ribbon. After his widow moved to Freiburg im Breisgau on June 20, 1907, she had the remains of her husband and her first-born son Ernst (* January 18, 1884, † July 31, 1884) transferred to the main cemetery there. Quoted from: Karl Huther: Arnold Fanck . In: Frankenthal once and now , issue 1, April 1964

- ↑ The grave of Christoph Friedrich Fanck (* December 4, 1846 - June 16, 1906) and Karolina Ida Fanck (* January 10, 1858 - May 16, 1957), born Paraquin, is located in field 49 of the main cemetery of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, Friedhofstrasse 8. The two sons Ernst Fanck and Arnold Fanck (* March 6, 1889, † September 28, 1974) were buried in the same grave. Field 49 is located between the consecration hall and the pond. Quoted according to the cemetery administration of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, Ana-Maria Grethler, July 17, 2020

- ↑ a b c Arnold Fanck . In: Main cemetery Freiburg im Breisgau, on: findagrave.com

- ↑ a b c Arnold Fanck . In: Munzinger Online / Personen - Internationales Biographisches Archiv , on: munzinger.de

- ↑ The family of Arnold Fanck's mother was called Parachini and later also Paraquino. Quoted from: Rudolf H. Boettcher: Adolph Ernst Theodor Berkmann - "Aufreitzender preacher and Megalosaurus" In: The family ties of Palatine Revolution 1848/1849 - A contribution to the social history of a bourgeois revolution special issue of the Society of Palatine-Rheinische Genealogy , Volume 14, Issue 6. Ludwigshafen am Rhein 1999. pp. 292, 302-303

- ↑ The grave of Ernst Fanck (* January 18, 1884; † July 31, 1884) is in field 49 of the main cemetery of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, Friedhofstraße 8. The parents of Christoph Friedrich Fanck (* December 4, 1846 ; † June 16, 1906) and Karolina Ida Fanck (born January 10, 1858; † May 16, 1957), née Paraquin, and Arnold Fanck (born March 6, 1889; † September 28, 1974) are buried. Field 49 is located between the consecration hall and the pond. Quoted according to the cemetery administration of the city of Freiburg im Breisgau, Ana-Maria Grethler, July 17, 2020

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Renate Liessem-Breinlinger: Fanck, Arnold . In: Baden-Württembergische Biographien , Vol. 2. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 978-3-17-014117-9 , pp. 121-123, on: leo-bw.de

- ^ Roman Zaremba h. wł. (Family tree) , on: seijm-wielki.pl

- ↑ Arnold Ernst Fanck's biological mother Sophie Marinucci, b. Meder, was noted in the registration card entry for Arnold Ernst Fanck at the Freiburg im Breisgau residents' registration office on April 24, 1954. Quoted from: Stadtarchiv Freiburg im Breisgau, Anita Hafner, July 13, 2020. At that time she was married to Giuseppe Marinucci, who worked for Universal-Dr. Fanck Greenland Expedition had been employed by Arnold Fanck as a cook.

- ↑ Student directory of the Free School Community in Wickersdorf . In: Archives of the German Youth Movement , Ludwigstein Castle near Witzenhausen in Hesse; Quoted from: Prof. Dr. Peter Dudek

- ↑ Lisa Stefanek . In: Hauptfriedhof Freiburg im Breisgau, on: billiongraves.de

- ↑ Elisabeth Fanck, born child, later remarried, which is why she had the family name Stefanek. Quoted from: Renate Liessem-Breinlinger: Fanck, Arnold . In: Baden-Württembergische Biographien , 2, Vol. 2. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 978-3-17-014117-9 , pp. 121-123, on: leo-bw.de

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Arnold Fanck , on: filmportal.de

- ↑ Fanck, A., Dr., director, Kaiserallee 33/34, Wilmersdorf , house owner: Patriotic women's association . In: Berliner Adressbuch , edition 1930, first volume, part IV, Wilmersdorf, p. 1457

- ↑ Fanck, A., Dr., Regiss., Kaiserallee 33/34, Wilmersdorf , house owner: Patriotic women's association . In: Berliner Adressbuch , edition 1931, first volume, part IV, Wilmersdorf, p. 1465

- ^ Fanck, Arnold, director, Wilmersdf, Kaiserallee No. 33, 34 , house owner: Patriotic women's association . In: Berliner Adressbuch , edition 1934, first volume, part I, p. 525

- ↑ Fanck, A., Dr., Regiss., Am Sandwerder 39 (Post Bln.-Wannsee, Bahnhofstrasse), owners as Am Sandwerder 37: Mendel, B., Dr. (Holland) . In: Berliner Adressbuch , edition 1935, first volume, west 380, part IV, Nikolassee, p. 1356

- ↑ House at Am Sandwerder 39 . In: Landesdenkmalamt Berlin , monument database, object no. 09075519, on: berlin.de