Neurolinguistics

The Neuro Linguistics is a part of linguistics that deals with how language is represented in the brain. The relationship between brain structures and processes on the one hand and language skills and language behavior on the other hand is examined. Neurolinguistics combines findings from neurology, in particular how the brain is structured and how it works, with findings from linguistics, in particular how language is structured and how it works.

Traditionally, the focus of neurolinguistics is on the study of aphasia , i. H. Speech disorders that can occur in adults after brain damage from illness or an accident. The study of these language disorders promises to be able to draw conclusions about the structure and processing of language in healthy adults. In addition to the traditional study of aphasia, neurolinguistics has now focused on other research areas: These include non-organic disorders of language production such as slip of the tongue or stuttering, as well as disorders of language acquisition. In addition to the observation and analysis of aphasia, today's neurolinguistics also uses a variety of other methods for researching language processing in the brain, including experiments, computer simulations and medical imaging .

History of Neurolinguistics

Beginnings

Although neurolinguistics as a scientific discipline is relatively young, the focus on the subject of investigation goes back a long way into the past. If one looks for initial research on the connection between language and the brain, a particularly early testimony is an ancient Egyptian papyrus roll, dated 3000 years BC, which was acquired by Edwin Smith in 1862 and is named after him the Edwin Smith papyrus . The 20th case there is a patient who has lost his ability to speak due to an injury to his temple, which is probably the first documented case of aphasia.

In ancient times, in the Middle Ages, in the Renaissance and in the 17th and 18th centuries one finds descriptions of language loss in individuals again and again. The compendium of the doctor Johannes Schenck von Grafenberg called Observationes medicae de capite humano should be emphasized . The compendium contains observations on language disorders by 20 Greek authors, five classical Latin authors, eleven medieval Arabic and Jewish authors, over 300 late Latin-speaking authors and 139 non-medical practitioners. The works of Johannes Jakob Wepfer are typical of the research in the 17th and 18th centuries: The works describe the symptoms of speech loss carefully, but no attempt is made to explain them.

Broca and Wernicke

Significant advances in understanding the relationship between language and the brain were made in the 19th century. At the beginning of the 19th century, the German anatomist Franz Joseph Gall assumed that language could be localized in a certain area in the brain. Gall's theses are just one example of many, and the validity of the localization principle has been discussed in many articles on speech pathology, both the localization of language production and comprehension, as well as reading and writing. These discussions created the intellectual climate in which Paul Broca's research fell on fertile ground.

A breakthrough for neurolinguistic research was the work of Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke in the second half of the 19th century, who dealt more closely with the question of localization and therefore observed aphasia patients. Part of the results was a classification of aphasic patients according to their symptoms: there are patients who speak fluently, but have difficulty accessing their vocabulary, with the result that they use many of their own word creations or paraphrases. This type of aphasia was later known as Wernicke aphasia . Other patients, on the other hand, have difficulties with grammar and especially with sentence structure; their language is shortened, in the manner of a telegram style ( agrammatism ). This type of aphasia has entered the literature as Broca's aphasia .

One result of Brocas and Wernicke's research is the assumption of two special areas in the brain reserved for language, the Wernicke and Broca areas , whose disruption or injury is said to be responsible for Wernicke and Broca aphasia. We now know that this view was a simplification, because it can now be shown that neural networks outside the Wernicke and Broca areas are involved in language processing. We also know today that Wernicke and Broca areas are also involved in recognizing music.

20th century

From the first half of the 20th century, the American neurologist Theodor Weisenburg and the psychologist Katherine MacBride should be mentioned, who developed large test batteries for aphasia and published test results from a large number of patients ( Aphasia: a clinical and psychological study , 1935).

The beginnings of neurolinguistics as an established discipline of linguistics go back to the 1960s. For example, doctors first recognized the need to work more closely with linguists in order to provide a sound description of the linguistic impairments in aphasic patients. In the 1960s z. In the USA, for example, the neurologist Norman Geschwind runs an interdisciplinary aphasia center (Boston School). In the German-speaking world, the Aachen school around Klaus Poeck should be mentioned, in which neurologists and linguists have been working closely together since the 1970s.

The popularization of the term neurolinguistics (English neurolinguistics ) is often attributed in the literature to the linguist Harry Whitaker. Whitaker became the founder of the journal Brain and Language and the editor of a series of books, Studies in Neurolinguistics .

Neurolinguistics has made decisive progress since the 1990s with the establishment of new technologies for measuring and displaying processes in the brain. With electroencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging, it was possible to examine the brains of damaged and healthy people in detail. It was possible to make more precise statements about how healthy people process language and how a damaged brain compensates for the damage.

Adjacent disciplines

Neurolinguistics is an interdisciplinary research area and draws on research results from other disciplines, including linguistics, neuroanatomy , neurology , neurophysiology , psychology , speech pathology and computer science . Neurolinguistics is most closely related to psycholinguistics . Both disciplines deal with the mental processes involved in language processing and language production. In contrast to psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics makes explicit reference to the anatomical and physiological aspects of the brain. While psycholinguistics primarily comes from the medical-psychological tradition and uses psychological methods to research speech perception, language production and, above all, child language acquisition, the focus of neurolinguistics is on research into language disorders such as aphasia and neurocognitive processes in people with healthy speech using modern imaging methods such as the functional magnetic resonance imaging . The Clinical Linguistics then acts as an application subject for which neurolinguistics provides the theoretical basis.

Research content

Central questions

Central questions in neurolinguistics include:

- What happens to language and communication after different types of brain damage?

- What happens if there is a language disorder during language acquisition?

- How can you measure and visualize processes in the brain that have to do with language and communication?

- What do good models of language and communication processes look like?

- What can computer simulations of language processing, language development and language loss look like?

- How should experiments be designed that can test models and hypotheses for language processing?

The first question occupies a central place in neurolinguistic research. The examination of adult speakers who suffer from a speech disorder or a loss of speech due to brain damage (aphasia) is a classic field of neurolinguistics. Brain damage can z. B. caused by a heart attack , a cerebral haemorrhage or a brain trauma after an accident. Progressive neurological diseases such as dementia can also be the cause. In addition to language disorders in adults caused by an accident or an illness, neurolinguistics also deals with language disorders during child language acquisition. These include the specific language development disorder and development problems such as reading and spelling difficulties .

One hopes that neurolinguistics will also be able to answer controversially discussed fundamental questions of linguistics in the future: To what extent is the ability to acquire language “hardwired” in our brain? Is language ability a unique human ability? Can the individual components of language be assigned to specific areas in the brain? To what extent are language skills separable from thinking and other mental activities?

Interfaces to sub-areas of linguistics

The research content of neurolinguistics encompasses all sub-areas of descriptive linguistics, from phonology , the teaching of sounds, through vocabulary to syntax , the teaching of sentence structure, and pragmatics :

| Linguistic discipline | Subject area | Examples of research content |

|---|---|---|

| Phonology | Sounds, sound structure | Phonemic paraphrases (replacement, insertion or deletion of phonemes ), e.g. B. instead of butcher (dt. 'Butcher') with aphasic rather betcher , butchler or buter ;

Disturbances in word stress , intonation or tone in tonal languages |

| Lexical semantics | Word meaning | Word substitutions in aphasic patients, e.g. B. Cat instead of dog , poodle instead of dog or head instead of cap |

| Morphology and syntax | Word formation and sentence structure | agrammatic utterances by patients with Broca's aphasia |

| Pragmatics | Use of language, language in the context of action | Problems recognizing speaker's intentions in aphasic patients with damage in the left hemisphere;

disorganized, rambling utterances in patients after traumatic brain damage |

Examples of important research results

The traditional assumption of clearly defined language regions in the brain, as it was still in the foreground with Broca and Wernicke, is now considered outdated. Today we know that the Broca region is not exclusively responsible for speech production and the Wernicke region is not exclusively responsible for speech reception. In addition, other areas of the brain that are also relevant for language processing have now been identified. Furthermore, research has recognized that groups of neurons are not only assigned to one brain function, but that they can take on various tasks. This means that there is no fixed assignment of brain regions to functions such as language processing. Neurolinguistics can also contribute research results to language acquisition: Thanks to neurolinguistic studies, one knows that the thesis of the so-called critical phase of language acquisition is not tenable. After all, neurolinguistic studies have shown that intonation plays a crucial role in processing sentence meaning.

Research methods

Historical methods

The classic research method in neurolinguistics is the observation and analysis of the language of people with aphasia with the aim of drawing conclusions about language processing in healthy people and with the intention of receiving suggestions for speech therapy. The observation of patients with aphasia and the autopsy of the deceased was also the method used in the classic studies of Broca, Wernicke and other researchers in the late 19th century. Furthermore, when it was necessary to operate on patients with epilepsy or a brain tumor, the surgeon also stimulated individual brain regions and concluded from the reactions which brain regions should be spared during the operation in order to avoid later speech impairment in the patient.

The so-called Wada test , with which one hemisphere is anesthetized in order to find out where the patient's speech-dominant hemisphere is located, is one of the now historical methods for the clinical examination of language function . Furthermore, electrical stimulation of cortical areas in the brain can trigger functional disorders and thus speech inhibitions at these points for a short time. In this way - it was hoped - one could identify the brain regions involved in the language process. In the meantime, however, we know from various studies and a comparison with imaging methods that these measurements are only reliable to a limited extent.

Static imaging

The enormous advances in imaging and measurement methods for displaying brain activities mean that it is now also possible to observe the language processing of healthy adults without medical or ethical problems. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance tomography provide a static image of the brain. However, if one wants to observe the processes in the brain, dynamic measurement methods are used: These include measurements of electrical activity in the brain and dynamic imaging methods.

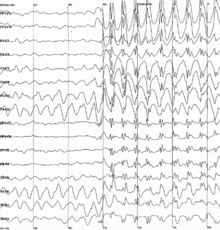

Measurement of electrical brain activity

The electroencephalogram (EEG) is a method with which one can measure the electrical activity of larger groups of neurons without the risk of radiation (in contrast to the PET scan ) . The magnetic encephalogram (MEG) does not measure the electrical, but the magnetic field that results from neuron activity in the brain. If you also want to identify the EEG signals that are triggered by a certain stimulus, e.g. If, for example, a spoken sentence has been triggered, the measurement is subjected to an ERP analysis: With the ERP analysis (ERP = event-related potential ), the spontaneous reactions are filtered out of all brain electrical potentials, so that only the potentials remain that coincide in time with the stimulus (e.g. the spoken sentence).

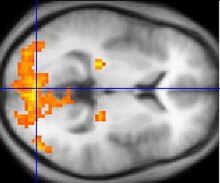

Imaging of the working brain

In addition to measuring and analyzing electrical brain activity, imaging methods such as PET scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used, which provide insights into the working brain and thus especially into language processing.

Measurement of cerebral blood flow

Finally, information about the functioning of the brain can also be obtained by measuring the cerebral blood flow ( regional cerebral blood flow , rCBF). So you can z. B. Let test subjects generate words (word fluency test or word fluency task) and measure the increase in blood flow in the hemispheres. In this way, u. a. determine the language-dominant hemisphere of the brain.

literature

Introductions

- Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 .

- Jürgen Dittmann, Jürgen Tesak: Neurolinguistics . Groos, Heidelberg 1993, ISBN 3-87276-696-1 .

- John CL Ingram: Neurolinguistics: an introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007.

- Helen Leuninger: Neurolinguistics. Problems, paradigms, perspectives . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1989, ISBN 3-531-11866-8 .

- Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 .

History of Neurolinguistics

- P. Eling: Language Disorders: 19th Century Studies . In: K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 394-397.

- P. Eling: Language Disorders: 20th-Century Studies, Pre-1980 . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 397-400.

- HA Whitaker: Neurolinguistics from the Middle Ages to the Pre-modern Era . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 597-605.

Special literature

- Adele Gerdes: Language acquisition and neural networks. The connectionist turn. Tectum, Marburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8288-9668-0 .

- Dieter Hillert: The Nature of Language. Evolution, Paradigms and Circuits . Springer, New York (NY) 2014, ISBN 978-1-4939-0608-6 (English).

- Carsten Könneker (Ed.): Who explains people? Brain researchers, psychologists and philosophers in dialogue . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2006, ISBN 978-3-596-17331-0 .

- Mary McGroarty (Ed.): Neurolinguistics and cognitive aspects of language processing. In: Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. Volume 28. Cambridge 2008.

- Brigitte Stemmer, Harry A. Whitaker (Eds.): Handbook of the Neuroscience of Language . Elsevier, Amsterdam a. a. 2008.

Web links

- Language and the Brain - A Neurolinguistic Tutorial , University of Stuttgart

- Fabian Bross: “You can recognize people by speech” - a short history of psycho- and neurolinguistics . In: Aventinus. The historical internet magazine by students for students. Issue 6, 2008.

- Lise Menn: Neurolinguistics , Linguistic Society of America.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Helen Leuninger: Neurolinguistics. Problems, paradigms, perspectives . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1989, ISBN 3-531-11866-8 , p. 17.

- ^ A b Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 3.

- ↑ Jürgen Dittmann, Jürgen Tesak: Neurolinguistics . Groos, Heidelberg 1993, ISBN 3-87276-696-1 , p. 3.

- ↑ Fabian Bross:“You can recognize people by speech” - a short history of psycho- and neurolinguistics . In: Aventinus. The historical internet magazine by students for students. Issue 6, 2008, accessed on May 21, 2020.

- ^ HA Whitaker: Neurolinguistics from the Middle Ages to the Pre-modern Era . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, p. 597.

- ^ HA Whitaker: Neurolinguistics from the Middle Ages to the Pre-modern Era . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 597-599.

- ^ P. Eling: Language Disorders: 19th Century Studies . In: K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 394-395.

- ↑ Fabian Bross:“You can recognize people by speech” - a short history of psycho- and neurolinguistics . In: Aventinus. The historical internet magazine by students for students. Issue 6, 2008, accessed on May 21, 2020.

- ↑ Lise Menn: Neurolinguistics , Linguistic Society of America, accessed May 21, 2020.

- ↑ P. Eling: Language Disorders: 20th-Century Studies, Pre-1980 . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, p. 398.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , p. 18.

- ^ John CL Ingram: Neurolinguistics: an introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , pp. 3-4.

- ↑ P. Eling: Language Disorders: 20th-Century Studies, Pre-1980 . In: K. Brown (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics . Elsevier, Oxford 2006, pp. 399-400.

- ↑ Lise Menn: Neurolinguistics , Linguistic Society of America, accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 4.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , pp. 16-19.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 5.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 6.

- ^ John CL Ingram: Neurolinguistics: an introduction to spoken language processing and its disorders . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , pp. 56, 63.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 85.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 68.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , pp. 103, 105.

- ↑ Horst M. Müller, Sabine Weiss: Neurology of Language: Experimental Neurolinguistics . In: Horst M. Müller (Ed.): Arbeitsbuch Linguistik , 2nd edition. Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, ISBN 978-3-8252-2169-0 , pp. 416-417.

- ^ Lise Menn: Neurolinguistics , Linguistic Society of America, last accessed May 21, 2020.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , p. 162.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , pp. 110-120.

- ^ Elisabeth Ahlsén: Introduction to Neurolinguistics . Benjamin, Amsterdam 2006, ISBN 90-272-3234-2 , pp. 162-163.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , pp. 127-132.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , p. 137.

- ^ Horst M. Müller: Psycholinguistics - Neurolinguistics. The processing of language in the brain . UTB, Paderborn 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3647-2 , pp. 149–151.