Newgrange

| Newgrange Sí to Bhrú | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Newgrange after the partial reconstruction |

||

|

|

||

| Coordinates | 53 ° 41 '39 " N , 6 ° 28' 36" W | |

| place | County Meath , Ireland | |

| Emergence | 3150 BC Chr. | |

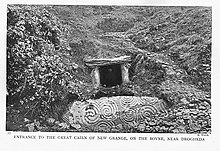

Newgrange ( Irish : Sí an Bhrú ) denotes a large Neolithic passage tomb in County Meath, Ireland on the River Boyne . The type is a Passage Tomb with a cruciform chamber and cantilever vault , which is not common, but also occurs in Knowth , Anglesey and Orkney . It is an Irish national monument .

The name "Newgrange" goes back to the fact that the area became part of the lands of Mellifont Abbey in 1142 . This is how the name "new grange" ("new homestead") came about. In Irish , the area is referred to as Brú na Bóinne [ ˈbruː nə ˈboːn „]" hostel / abode on the (river) Boyne "or originally" abode of the (goddess) Bóinn ".

meaning

Newgrange lies above a wide bend in the river in one of the most fertile and therefore agriculturally intensively used areas of Ireland. The complex was built around 3150 BC. Built in BC. It is one of the world's most important megalithic sites . In the immediate vicinity are Dowth and Knowth, two other important megalithic sites that seem to be temporal precursors. In 1993 the Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth facilities were declared World Heritage Sites.

history

Newgrange fell into disrepair over the centuries; the burial mound eroded and was perceived as a natural hilltop. Trees grew on the site and the hill was used as grazing land. In 1699, landowner Charles Campbell accidentally discovered the grave when he was removing a pile of stones. Edward Lhuyd of Oxford University , who was touring Ireland at the time, made careful notes and drawings of the condition in 1699. The next scientist to describe Newgrange around 1725 was Sir Thomas Molyneux , a physics professor at the University of Dublin . He mentioned that two human skeletons were found on the floor of the tomb. Sir Thomas Pownall was the third scientist to explore the site around 1770. He attributed the megaliths to the Phoenician seafarers . Many later descriptions are based largely on the accounts of these three men.

In 1882, the Ancient Monument Protection Act came into force, placing Newgrange, Dowth and Knowth under the protection of the state. The competent authority excavated some of the ornate stones in the late 19th century without conducting any systematic research. In 1911, George Coffey's book New Grange and other Incised Tumuli in Ireland was a detailed archaeological description. Excavations took place on the outer stone ring in 1928 and 1956. In the 1950s, flint devices and a Dexel were discovered in the area . As a result, the chief archaeologist of the Irish Tourism Authority ( Bord Failte ) planned systematic excavations.

These took place from 1962 under the direction of Michael J. O'Kelly from Trinity College Dublin. During these extensive excavations, an astronomical orientation of the entrance was recognized. Inside, the remains of five people and various grave goods were discovered in 1967. The mortar used inside to waterproof the roof was radiocarbon dating to the year 3200 BC. Dated.

A DNA analysis from a man's bone find in 2020 showed that this person's parents were first-degree relatives; that is, his parents were either brother and sister or one parent was the other's child.

reconstruction

Michael O'Kelly also directed the reconstruction , which lasted until 1975. The aim was to give the visitor a realistic picture of the original facility. In addition, access for visitors to the interior of the facility should be made possible. The entrance was designed by O'Kelly in 1972, and numerous concrete supports were installed inside.

In addition to these drastic interventions, the facade is also a point of criticism. The appearance today is an interpretation of O'Kelly's findings. Some critics claim that a retaining wall at this angle was not feasible with the technology of the time. O'Kelly used reinforced concrete . The quartz stones that were built into the retaining wall were found widely scattered. It is not known how they were originally arranged. Professor George Eogan doubts the interpretation made. In Knowth the stones were then left on the ground.

construction

The system has a diameter of a good 90 meters. The hill consists mainly of stone and turf, bounded by a stone ring which, according to the scientists, originally consisted of a three meter high granite wall and white quartzite on the access side . It was recreated accordingly after the excavation.

A corridor about 22 meters long under the hill ends in a cross-shaped burial chamber. It has a cantilever vault about seven meters high and is still waterproof after over 5000 years. In one of the three niches of the chamber there was a large ornate altar block (as in Knowth) with a shallow hollow. Burned human bones were found on it. About 13 days each year around the winter solstice at sunrise, a ray of light penetrates for about 15 minutes through an opening above the entrance directly into the corridor and the chamber. Because the earth's axis oscillates over the course of many thousands of years because of the precession , the light effect is somewhat weaker today than when it was built; The light beam no longer reaches the rear panel of the inner chamber, but ends about a meter in front of it.

This system has the closest structural equivalent in its predecessor Knowth, (a few hundred meters away). There are indications that the entire complex, like that of Knowth, was surrounded by an ornate stone ring; of this only twelve stones are evident.

In the vicinity of the facility there was a settlement of grooved goods and the bell beaker culture .

tourism

It is possible to visit Newgrange; however, access is strictly regulated. So it is not possible to enter the Stone Age monument individually, you can only get about 100 meters to the fenced-in complex. Tours must be booked at the visitor center on the other side of the river, then you can enter the chamber with a guide.

Legends and tales

According to legend, the great Irish hero Cú Chulainn ("Dog of Culann") was conceived or born in Newgrange, reported by his exploits in the Ulster cycle . He is said to have been a son of the sun god Lugh and the legendary figure Deichtire . Another legend reports that after the conquest of the island by the Milesians of the Dagda of the mythical Túatha Dé Danann each of the remaining gods was awarded an elven hill and his son Aengus Mac Oc was henceforth the largest of the barrows ( Bruig na Boinne , the tumulus of Newgrange) served as a residence.

See also

literature

- Werner Antpöhler: Newgrange, Dowth and Knowth. A visit to Ireland's "Valley of the Kings" . Neue Erde, Saarbrücken 1997, ISBN 3-89060-022-0 .

- Werner Antpöhler: Newgrange, Dowth & Knowth. A visit to Ireland's Valley of the Kings . Mercier, Cork 2000, ISBN 1-85635-317-6 .

- George Coffey: New Grange (Brugh na Boinne) and other Incised Tumuli in Ireland. The Influence of Crete and the Aegean in the extreme West of Europe in early Times. Hodges, Figgis & Co. Ltd., Dublin 1912, (new edition. Dolphin Press, Poole 1977, ISBN 0-85642-041-7 ).

- Michael J. O'Kelly : Newgrange. Archeology, art and legend . Thames and Hudson, London 1982, ISBN 0-500-39015-0 .

- Elizabeth Shee Twohig: Irish megalithic tombs (= Shire Archeology . Volume 63 ). 2nd Edition. Shire Publications, Princes Risborough 2004, ISBN 0-7478-0598-9 .

- Geraldine Stout: Newgrange and the Bend of the Boyne (= Irish Rural Landscapes . Band 1 ). Cork University Press, Cork 2002, ISBN 1-85918-341-7 .

- Peter Harbison : Guide to the Naional Monuments in the Republic of Ireland Gill and Macmillan, Dublin 1992 ISBN 0-7171-1956-4 .

Web links

- Entry on the UNESCO World Heritage Center website ( English and French ).

- Oliver Schwarz: Private page about Newgrange ( Memento from October 15, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- Page about Newgrange, Dowth and Knowth on knowth.com (English)

- Review of Alan Marshall's excavation on knowth.com

- Video

Individual evidence

- ↑ Brú na Bóinne - World Heritage Site ( Memento of the original of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on heritagecouncil.ie (PDF)

- ^ Newgrange. Voices from the Dawn, accessed June 14, 2015 .

-

^ Lara M. Cassidy et al .: A dynastic elite in monumental Neolithic society. In: Nature . Volume 582, 2020, pp. 384-388, doi: 10.1038 / s41586-020-2378-6 .

Incest in the stone age elite. Dead in the passage grave of Newgrange turns out to be the child of first-degree relatives. On: scinexx.de from June 18, 2020. - ↑ Cu Chulainn Champion of Ulster. discoveringireland.com, accessed June 15, 2015 . or Doreen McBride: Louth Folk Tales . The History Press, Dublin 2015, ISBN 978-1-336-18471-8 .

- ↑ Robert Fischer: The Celtic religion in Ireland and its influence through Christianization. (PDF) univie.ac.at, p. 14 , accessed on June 15, 2015 .