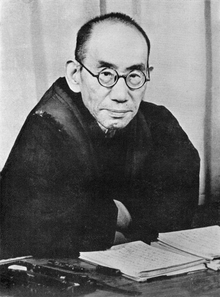

Nishida Kitaro

Nishida Kitarō ( Japanese 西 田 幾多 郎 ; * May 19, 1870 in Mori near Kanazawa (today: Kahoku , Ishikawa Prefecture ); † June 7, 1945 in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture ) was a Japanese philosopher . He is considered the spiritual father of the Kyoto school and marks the beginning of modern Japanese philosophy .

Life

As a scion of an old samurai family , Nishida had a privileged childhood. Due to his weak constitution, he was very cared for by his mother Tosa, a devout Buddhist . He repeatedly asked his father, Yasunori, to attend a secondary school in Kanazawa . The father rejected his request because he saw him as his successor in the office of village mayor and feared that this office would not be sufficient for his son later. In the end, he did allow him to attend secondary school. However, an illness soon forced Nishida to take private lessons.

From 1886 to 1890 Nishida then again attended a school, the Ishikawa Semmongakkō. When the political climate at the school changed, Nishida practiced passive resistance. He was eventually denied advancement to the next class because of "bad behavior". Nishida left school.

In 1891 he began studying philosophy at the Imperial University of Tokyo . He took a "special course" due to his missing high school diploma. As a result, he was exposed to discriminatory treatment and withdrew more and more into himself. That changed when Raphael von Koeber came to the university in 1893 . This motivated him to familiarize himself with Greek and medieval European philosophy and introduced him to the works of Schopenhauer .

He also studied German literature with Karl Florenz together with Natsume Sōseki . He finished his studies shortly before the outbreak of the first Sino-Japanese War with a thesis on David Hume .

In May 1895, Nishida married his cousin Tokuda Kotomi, with whom he had a total of eight children. Some of the six daughters died while their father was still alive, and the older of the two sons Ken died in 1920 (at the age of 23).

In 1896 he took over the post of teacher at his former school in Kanazawa, which had since been restructured into a high school. The next year he began taking Zen meditation lessons, probably inspired by his schoolmate and friend, D. T. Suzuki . During his stay at the Taizō-in temple in Kyōto , which he attended on the occasion of a lengthy Zen meditation retreat ( sesshin ), he was offered a position at the high school in Yamaguchi by his teacher Hōjō Tokiyoshi in August 1897 , which he accepted without hesitation.

Because of his work Zen no kenkyū ( About the good ) he was offered a position at the Imperial University in Kyoto in 1910 , where he became professor of philosophy in 1914. It was here that Nishida further developed his philosophy and attracted the core of what would later become the Kyōto School when he became known in the 1920s. He retired in 1928 and moved to Kamakura to further develop his logic of the place .

In 1940 he was awarded the Japanese Order of Culture .

Nishida died on June 7, 1945 in Kamakura of kidney disease. His grave is there in the cemetery of the Zen temple Tōkei-ji .

philosophy

Nishida Kitarō has influenced modern philosophy in Japan like no other to this day. His attempt to combine Western methodology and terms with Eastern ideas pervades the efforts of Japanese philosophers to this day. Nishida's concerns and vocabulary also shape the style of the so-called Kyoto school , the spiritual father of which he and his successor Tanabe Hajime are considered to be.

Nishida was convinced that philosophy can only be about finding “the one truth”. For this, however, he considered it important to think philosophy and religion together and referred to Indian or early Greek philosophy , in which he saw both still united. His philosophy therefore represents the attempt to find a synthesis of philosophy and religion .

Nishida's thinking can be divided into five creative phases: Based on the concept of the investigation of consciousness and the concept of pure experience derived from it , he then examined the problem of self-awareness and will. In the third phase he arrived at his logic of place ( basho no ronri ), which finally leads to the concept of absolute nothingness ( zettai mu ). Both terms have a strong influence on the discussion in Japanese philosophy to this day. The fourth phase is determined by a dialectical thinking, in which he develops the standpoint of the dialectically general ( benshōhōteki ippansha ) and the contradicting self-identity ( mujunteki jiko dōitsu ).

In his last creative phase, Nishida turned completely to the philosophy of religion and the questions “When does religion become a problem for us”, “What does God, Buddha, absolute being, that which is absolutely contradicting mean” and “When does our self touch God, Buddha. “Nishida saw the origin of religion in suffering in the urge to know oneself.

Pure experience

Nishida based his concept of pure experience ( 純 粋 経 験 junsui keiken ) on William James , on Bergson's concept of the lifeworld and on Christian mysticism. For him, it encompassed the immediate moment of perception , when no distinction has yet been made between the perceiving subject and the perceived object and no judgment has yet been made about what has been perceived. For this reason, pure and immediate experience are one: a tone can be perceived or a color can be seen without having to distinguish between the subject (one's own person) and the object (the thing perceived).

“ Pure describes the state of a real experience as such, to which there is not even a trace of thought work attached. […] That means, for example, that at the moment we see a color or hear a sound, we neither consider whether it is a question of the effects of external things, nor whether an ego feels them. Even the judgment of what this color and this tone actually is has not yet been made at this level. Thus pure and immediate experience are one. In the direct experience of the state of consciousness there is still no subject and no object. "

He called a consciousness in this state of non-differentiation concrete consciousness ( gutaiteki ishiki ). It also forms the basis for the later differentiation of what is perceived through thinking ( shii ). Every differentiation of what is perceived is retrospective, since it no longer takes place in the now consciousness (the moment of pure experience), but imagines its object as the past, it separates, separates and differentiates. For Nishida, therefore, the primacy was with pure experience, all subsequent abstraction processes have this as a prerequisite and are necessarily poorer in their content than this.

Nishida attested the differentiated consciousness a striving to return to the original unity of pure experience. He saw a possibility for this in the will ( ishi ), since it overcomes the subject-object dualism in the immediacy of the act. With this return to unity, the will achieves something that discursive thinking must be denied.

For Nishida, intellectual perception ( chiteki chokkan ) was able to overcome the subject-object division even more than will . Intellectual perception structures the world, and only allows something like things to emerge through the formation of conciseness. In the perception, there is not a sum of unprocessed meaningful data, but things are always perceived, these can also contain ideal elements:

"If our consciousness were just a thing of sensory characteristics, it would probably stop at a state of ordinary intellectual perception, but the mind demands infinite unity, and that unity is in the form of so-called intellectual intuition."

Nishida later expanded this epistemological investigation into an ontological one with the question “What is reality?” . For Nishida, reality was synonymous with activity of consciousness, because from the point of view of pure experience man and world are not separate.

Nishida saw a way of thinking about God in the unifying power that makes the return to Pure Experience and Original Unity possible. Thus, precisely because of the unification of the opposites, God would not have to be thought of as outside the world, nor as pantheistic and at the same time would be bound to an experience that is accessible to us. Nishida then saw the good ( 善 , zen ) as the fruit of this unifying power, which can express itself as love, free will, joy and peace.

Analysis of self-confidence

Nishida defines self-confidence ( jikaku ) as one of the transcendental self ( lower kenteki jiga ), which is expressed in absolute free will. The model for the analysis of the will developed in his second creative period was for Nishida the " act of deed " by Johann Gottlieb Fichte . Absolutely free will ( kōiteki shukan ) is of a creative dynamic that cannot be reflected in its genuity, since it evokes reflection in the first place. It is linked to the eternal nun ( eikyū no ima ).

However, this approach , which was based on German idealism , later appeared to Nishida too one-sided due to its subjectivity and he tried to overcome it in his logic of the place .

Logic of the place

All knowledge takes place in judgments. According to Hegel , Nishida understands the judgment as follows: The individual is the general. The knowledge that takes place in judgments is the self-determination of the general. Because the individual (the judging person) is not relevant for the meaning of the truth of the judgment. In this general of judgment the logical categories of the natural world have their place. Nishida understands “being” here as “having one's place” and thereby “being determined”.

Nishida distinguishes three possible worlds in general:

- The natural world : It is defined as general judgment ( handanteki ippansha ). It is the propositional world of objects thought and stated. The objects are because they have their place in the natural world. Their logical place, however, is not accessible even as a general judgment, it is only the background on which they appear. If the natural world wants to perceive itself, it must address itself as general self-perception ( jikakuteki ippansha ). She does this in awareness. The resulting relationship to oneself has its place in the world of consciousness.

- The same condition applies to the world of consciousness as to the natural one: its logical place lies beyond the world that it determines. This difference in turn compels the self to step through the world of consciousness and enter the intelligible world in order to gain self-awareness. Consciousness does not perceive itself, but is thought of as what is seen. It does not know of itself through perception, but through the fact that it intellectually determines itself as “consciousness with a content.” The place of this determination is therefore the intelligible world.

- The intelligible world is the world of ideas of the true ( shin ), the beautiful ( bi ) and the good ( zen ). Here the transcendental self is defined as spiritual being through intellectual intuition (the intelligible general ). The ideas correlate with aesthetic, moral and religious consciousness. The three ideas follow a certain hierarchy: Since artistic consciousness still sees a single self and not the free self, it must be absorbed in moral consciousness. Moral consciousness has no concrete object in the world as its subject, but the idea of the good. All being is an ought for it. However, it can only be achieved through religious consciousness, which in religious-mystical experience overcomes and transcends itself through self-negation. Its place is the Absolute Nothing, which cannot be represented philosophically and conceptually, since any statement about it would destroy its undifferentiated unity through separation and isolation.

Absolute nothing

The idea of truth now shows that the difference between world and place cannot be canceled out. The place remains the discursively unattainable background of the general. This leads Nishida to the conclusion that the general must have the meaning of the place. Since things that are independent of one another have an effect on each other, the location determines itself. Because as long as something mediates itself, it cannot affect others. Since the place determines itself, things affect each other.

However, the individual mediates itself. In order to overcome this subjective dialectic, Nishida interprets the place as unrepresentable and thus as nothing in the next step. The religious self does not refer to another place, but is itself its place, which cannot be understood. So this place is nothing and at the same time enables everything that exists. Nothing is place and place is nothing. Nishida describes this relationship as absolute nothing ( 絶 対 無 , zettai mu ).

literature

Primary literature

- Nishida Kitarō zenshū (Collected Works, 1966)

- Shisaku to taiken (Thinking and Experience, 1915)

- Jikaku ni okeru chokkan to hansei (views and reflection in self-awareness, 1917)

- Ishiki no mondai (The Problem of Consciousness, 1920)

- Geijutsu to dōtoku (Art and Morals, 1923)

- Hataraku mono kara miru mono e (From acting to seeing, 1927)

- Ippansha no jikakuteki taikei (The self-conscious system of the general, 1930)

- Mu no jikakuteki gentei (The self-confident determination of nothingness, 1932)

- Tetsugaku no kompon mondai (Fundamental Problems of Philosophy, 1933–34)

- Tetsugaku rombonshū (Collection of Philosophical Essays, 1935–46)

- Bashoteki ronri to shūkyōteki sekaikan (The logic of the place and the religious worldview, 1945)

- Yotei chōwa wo tebiki toshite shūkyōtetsugaku (Towards a Philosophy of Religion under the Direction of the Concept of Preestabilized Harmony, 1944)

German translations

- The intelligible world , three philosophical treatises, translated into German in association with Motomori Kimura, Iwao Koyama and Ichiro Nakashima and introduced by Robert Schinzinger , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1943

- Zen no Kenkyū (About the Good, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1989; paperback edition 2001, ISBN 978-3458344582 )

- Logic of Place: The Beginning of Modern Philosophy in Japan (translated and edited by Rolf Elberfeld ), Darmstadt, 1999. ISBN 3-53413-703-5 (paperback special edition 2011, ISBN 978-3534235858 )

- Self identity and continuity of the world . In: The Philosophy of the Kyôto School , Texts and Introduction, Ed. Ryôsuke Ohashi . Pp. 54-118. Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1990. ISBN 3-495-47694-6 (2nd edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-495-48316-9 )

- The Different Worlds (1917). Annotated translation with source citations added. Translated by Christian Steineck . In: Contributions to Japan Research: Commemoration for Peter Pantzer on his sixtieth birthday. Bonn, Bier'sche Verlagsanstalt 2002, 319–338. ISBN 978-3-936366-02-0

- The artistic creation as a creative act of history . In: The Philosophy of the Kyôto School , Texts and Introduction, Ed. Ryôsuke Ohashi. Pp. 119-137. Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1990. ISBN 3-495-47694-6 (2nd edition 2011, ISBN 978-3-495-48316-9 )

- Philosophy of Physics (translated by Toshiaki Kobayashi and Max Groh), Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2012. ISBN 978-3-86583-606-9

Secondary literature

- Lydia Brüll: Japanese philosophy: an introduction . WBG, Darmstadt 1989. ISBN 3-534-08489-6

- Peter Pörtner , Jens Heise : The Philosophy of Japan. From the beginnings to the present (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 431). Kröner, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-520-43101-7 , pp. 347-356.

- Robert E. Carter: The Nothingness Beyond God. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Nishida Kitaro . Paragon House Publishers, St. Paul 1997, ISBN 1-55778-761-1

- Ryôsuke Ohashi: From self-knowledge to logic of location. Nishida and phenomenology . In: Metamorphosis of Phenomenology. Thirteen stages from Husserl . Pp. 58-85. Alber Freiburg / Munich 1999. ISBN 978-3-495-47855-4 Liber amicorum for Meinolf Wewel .

- Thomas Latka: Topical social system. The introduction of the Japanese theory of place into systems theory and its consequences for a theory of social systems . Carl-Auer-Systeme Verlag, Heidelberg 2003, pp. 27-63.

- Myriam-Sonja Hantke: The poetry of the all-unity with Friedrich Hölderlin and Nishida Kitarô (= world philosophies in conversation . Volume 3). Verlag Traugott Bautz, Nordhausen 2009. ISBN 978-3-88309-502-8

- Special issue Kitarō Nishida (1870–1945) . Edited by Rolf Elberfeld. General journal for philosophy, issue 3/2011. Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart (Bad Cannstatt)

- Toshiaki Kobayashi : Thinking of the Stranger - Using the example of Kitaro Nishida . Stroemfeld Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 2002, ISBN 3-86109-164-X

- Shunpei Ueyama: The Philosophical Thought of Nishida Kitarōs . Translated by Hans Peter Liederbach. In: Japanese Thinkers in the 20th Century . Munich, Academium, 2000, pp. 96-164, ISBN 3-89129-625-8

- Elena Louisa Lange: Overcoming the Subject - Nishida Kitarōs西 田 幾多 郎(1870-1945) Path to Ideology . Dissertation, University of Zurich, 2011.

- Raji C. Steineck : "Built on nothing: the logical core of Nishida Kitarō's philosophy." In: Fichte Studien 2018 / Das Nothing and Being , pp. 127–150. DOI 10.1163 / 9789004375680_010.

Web links

- John Maraldo: Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Literature by and about Nishida Kitarō in the catalog of the German National Library

- Link catalog on the subject of Nishida Kitarō at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Digital copies of his works at Aozora Bunko (Japanese)

- Topological Turn and Japanese Philosophy

Individual evidence

- ^ Pörtner, Peter: Nishida Kitarō. About the good . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1989, pp. 10-16

- ↑ Site plan of the grave (Japanese website) ( Memento of the original from April 29, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ See Lydia Brüll: The Japanese philosophy: an introduction . Darmstadt 1989, p. 156

- ↑ See Lydia Brüll: The Japanese philosophy: an introduction . Darmstadt 1989, p. 168

- ↑ Lydia Brüll: The Japanese philosophy: an introduction. Darmstadt 1989, p. 157

- ↑ Nishida Kitarō: About the good . Insel Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. 1989, p. 29

- ↑ Quoted from Lydia Brüll: The Japanese philosophy: an introduction . Darmstadt 1989, p. 160

- ↑ Kitaro Nishida: Logic of the Place . Scientific Book Society Darmstadt ISBN 3-534-13703-5 . P. 286, also Brüll, p. 161

- ^ Robert Schinzinger: Japanese thinking . Verlag E. Schmidt, Berlin 1983, p. 62

- ↑ Peter Pörtner, Jens Heise: The Philosophy of Japan. From the beginning to the present . Stuttgart 1995, p. 352

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Nishida, Kitaro |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 西 田 幾多 郎 (Japanese) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 19, 1870 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mori, Kanazu (today: Kahoku , Ishikawa Prefecture ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 7, 1945 |

| Place of death | Kahoku , Ishikawa |