Orange riots

The Orange Riots were two violent riots in the New York borough of Manhattan in 1870 and 1871. They were clashes between Irish Protestants of the Orange Order and Catholic Irish. When the Catholics attacked the Orange March in 1871, troops from the National Guard , who were supposed to protect the march , shot into the crowd. Over 60 people were killed. The unrest sparked a campaign against the party organization of the Democrats under William Tweed , which led to the smashing of the so-called "Tweed Ring".

Riots 1870

On July 12, 1870, Orangemens Day , a procession of Irish Protestants was held in Manhattan, which marked the victory of William III. - the King of England and Prince of the House of Orange - celebrated the Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne . The route was from Eighth Avenue up to Elm Park on 92nd Street.

When the protesters mocked the Catholic Irish residents of Hell's Kitchen , many of them followed the move and returned the insults. At the park, 300 Irish workers joined the 200-strong mob and together they attacked the Protestants. The police stepped in to stop the fight. Eight people were killed in the riot.

Prehistory of the riots in 1871

The following year, the Orange Order asked the police for permission to march again. The Police Commissioner James J. Kelso forbade this, however, because he feared renewed outbreaks of violence. He was supported by William Tweed , the head of Tammany Hall , the party machine of the Democratic Party , which controlled the city and state. While the Catholic Archbishop John McCloskey applauded, Protestants criticized the decision. The New York Times and the New York Herald did the same in editorials. A petition was raised from businessmen on Wall Street, and Thomas Nast published a cartoon on the subject in Harper's Weekly . It wasn't just the ban on demonstrations that gave the impression that the behavior of the Catholic mob was being honored; there were also growing voices warning of the growing political power of Irish Catholics and the increasing visibility of left-wing Irish nationalism in the city, as well as fears of an overthrow like the Paris Commune .

This pressure, along with pre-existing criticism of Tweed's regime in general, led Tammany to change course and allow the move. Tammany had to show that they were able to control the Irish immigrants, who made up a significant part of their electorate. Governor John T. Hoffman - a Tammany man - lifted the ban on demonstrations and ordered that the move be protected by New York Police and National Guard units, including cavalry units .

Riots 1871

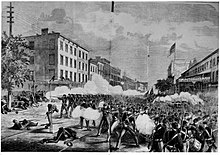

On July 12th the move took place under massive police protection. A total of 1,500 police officers and five regiments of the National Guard - with over 5,000 men - protected the parade. The move started at 1:30 p.m. at the Orange Headquarters, Lamartine Hall on Eighth Avenue and 29th Street. 21st through 33rd Streets were full of people, mostly Catholic and workers. Both sides of the avenue were cordoned off. The police and national guards appeared, to the displeasure of the crowd, and the few Orange people began their parade at 2 p.m., flanked by soldiers.

Almost immediately, the crowd started throwing stones, bricks, bottles and shoes at the protesters. When the National Guards responded with musket fire , pistols were fired from the crowd. The police tried to allow the parade to continue by pushing back the crowd with moderate baton use.

The move came under blockade again and was again attacked with thrown weapons, which led to new shots by the soldiers. The rush of the mob stopped the move, so that the police attacked them with their batons and the National Guard with their bayonets . Meanwhile, a hail of stones and kitchen ware fell on the security forces from the surrounding roofs. Ultimately, the soldiers fired into the crowd - without corresponding orders - and the police joined them with mounted units.

The procession marched to 23rd Street , where she turned left onto Fifth Avenue , where the crowd supported the Orange. The mood changed again as we continued south on Fifth Avenue to the entertainment district at 14th Street , where the crowd was hostile again. The move continued to the Cooper Union , where the Orange people disappeared.

The riots had claimed the lives of 60 civilians - mostly Irish workers - and three National Guardsmen. More than 150 were wounded, including 22 guardsmen and more than 20 police officers who were injured by objects thrown. Four suffered non-fatal gunshot wounds. More than 100 people were arrested.

The following day, 20,000 people demonstrated their respect for those killed in front of the Bellevue Hospital morgue . Funeral parades made their way to Calvary Cemetery in Queens . In Brooklyn , Governor Hoffman was hanged in effigy by Irish Catholics , and the riot has been referred to as "Eighth Avenue butchery".

Effects

Tammany Hall had allowed the move to secure its political power. However, it could not benefit from the effects; on the contrary, it was exposed to growing criticism from the newspapers and the city elite. Tweed fell shortly afterwards.

“One of the reasons many in the upper and middle classes had grudingly acquiesced in Tammany's hold on power was its presumed ability to maintain political stability. That saving grace was gone: Tweed could not keep the Irish in line. The time had come, said Congregationalist minister Merrill Richardson from the pulpit of his fashionable Madison Avenue church, to take back New York City, for if "the higher classes will not govern, the lower classes will ." ”

“One of the reasons that many of the upper and middle classes grudgingly accepted Tammany's rule was his attributed ability to provide political stability. That salvation was gone: Tweed couldn't keep the Irish under control. The time has come, said Congregational Rev. Merrill Richardson from the pulpit of his fancy church on Madison Avenue, to bring New York City back, because "if the upper classes don't rule, the lower classes would ."

Banker Henry Smith told the New York Tribune that "a lesson like this is necessary every few years." If 1,000 troublemakers were killed, the effect would be that all of the rest would be intimidated.

literature

- Russell S. Gilmore: Orange riots in The Encyclopedia of New York City , Yale University Press, New Haven 1995, ISBN 0300055366

- Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace: Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 , Oxford University Press, New York City 1999, ISBN 0195116348

Web links

- Hibernian Chronicle: The Orange riot - The Irish Echo

- TOM DEIGNAN writes about the deadly "Orange Riots" in New York City in 1871 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Daytonian in Manhattan: The Lost 1764 Apthorpe Mansion, November 29, 2010, accessed January 12, 2014

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Burrows & Wallace, pp. 1003-1008

- ↑ a b c Gilmore, p. 866

- ↑ On July 29, 1871, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about the Orange Riots in New York City

- ^ New York Songlines: 8th Avenue , accessed January 12, 2014

- ↑ a b Burrows & Wallace, p. 1008