Presidential election in Sri Lanka in 1988

The 1988 presidential election in Sri Lanka took place on December 19th. It was the second direct election of a president in Sri Lanka . During the election, Sri Lanka was in the middle of a civil war . In the north and northeast, the Tamil Tigers (LTTE) and the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) stationed there since July 1987 fought each other . In the south there was a climate of violence with numerous, often politically motivated murders, which was essentially caused by the terrorist actions of the Marxist-Sinhala-nationalist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). Due to the circumstances, the voter turnout was comparatively low at 55.3 percent.

The candidate of the United National Party (UNP), the incumbent Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa , emerged as the winner.

prehistory

Tamil-Sinhala conflict

The last presidential election in 1982 was won by the UNP's candidate, Junius Richard Jayewardene (UNP) , who has been in office since 1978 . In October of the same year Jayewardene had a referendum held, with which he had the voters confirm that the parliamentary election, which was actually scheduled for 1983, was to be postponed to 1989. The government justified the postponement of the election with the need for economic consolidation in Sri Lanka and received a majority in the referendum. However, the situation subsequently did not stabilize. The Sri Lankan Tamil minority had become increasingly radicalized in view of the ongoing discrimination and their political representatives had called for an independent Tamil state in Sri Lanka for the first time in the 1976 Vaddukoddai Resolution . The LTTE , which was founded illegally in 1976 through the amalgamation of various radical Tamil groups , carried out terrorist attacks on state institutions. In 1982 there were five deaths from terrorist acts by the LTTE. There were eight fatalities in the first half of 1983, including three Tamil UNP politicians. The actual beginning of the civil war marked the attack by Tamil terrorists on an army base with the killing of 13 Sinhala soldiers on July 23, 1983. This was followed by a week of violent ethnic unrest (" Black July "), in which a Sinhalese mob attacked Tamils . The riots left around 470 dead among the Tamil minority and resulted in around 80,000 officially registered refugees in camps. The government or local police force proved to be incapable of doing this and, in some cases, were also unwilling to curb the violence effectively.

In the following years the conflict escalated and escalated into full civil war . By 1987 this civil war cost at least 6,000 deaths (approximately 600 Sinhala civilians, 500 Sinhala military personnel, and 5,000 Tamils). More than 150,000 people fled abroad - most of them to neighboring India. The civil war hit the Sri Lankan economy hard. Military spending rose from 4% of the budget in 1976 to 17% in 1986. Other important government investments had to be postponed. The economically important tourism experienced a slump and unemployment rose sharply to more than one million people in 1987. By 1987, the conflict cost the Sri Lankan state at least 15 billion Sri Lankan rupees (about US $ 500 million).

The Indo-Sri Lankan Agreement 1987

On July 29, 1987, President Jayewardene and India's Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signed the India -Sri Lankan peace agreement in Colombo. The essential elements of this agreement were, on the one hand, the unification of the northern and eastern provinces to form a new north- eastern province (a long-standing demand of the Tamils) - subject to a referendum to be held later in the eastern province. The second essential point of the agreement provided for the temporary stationing of Indian troops in north-east Sri Lanka to ensure the controlled, peaceful disarmament of the LTTE and the Sinhalese defensive villages and the protection of the civilian population. The Sri Lankan government planned to reduce the army presence in the Tamil areas and disarm the self-protection militias loyal to the government. The LTTE was very reluctant to declare its willingness to self-disarm, and from October 1987 there were open armed conflicts between the LTTE and the Indian Peacekeeping Force (IPKF).

JVP insurrection

| Time to |

Political murders |

Other murders |

Armed robbery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 15, 88 | 10 | 25th | 34 |

| Feb 28, 88 | 8th | 31 | 17th |

| March 18, 88 | 10 | 41 | 16 |

| April 15, 88 | 6th | 44 | 13 |

| May 14, 88 | 20th | 18th | 19th |

| June 14th, 88 | 43 | 23 | 87 |

| July 14th, 88 | 24 | 65 | 40 |

| Aug 15, 88 | 23 | 88 | 158 |

| Sept. 15, 88 | 51 | 99 | 163 |

| Oct 14, 88 | 75 | 132 | 166 |

| Nov 14, 88 | 112 | 212 | 673 |

| Dec. 14, 88 | 82 | 323 | 115 |

The stationing of Indian troops in the north and east of the islands also formed a kind of catalyst for an uprising movement in the south of the island. Here, especially among young people, there was growing dissatisfaction with the deteriorating economic situation and the associated lack of prospects. The stationing of Indian troops on Sri Lankan soil was viewed by many Sinhalese with great suspicion. India was assumed to be secretly pursuing its own interests and wanting to integrate Sri Lanka into its direct sphere of influence. The leadership of the Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP, “People's Liberation Front”) wanted to take advantage of this tense mood and began a social revolutionary uprising movement with the aim of overthrowing the UNP government in Colombo. The JVP had attempted a coup in 1971, but it was soon crushed. The second uprising from 1987, which lasted until 1989, was better prepared and was far more serious and costly. Paramilitary organizations controlled by the JVP or dependent on it, such as the DJV ( Deshapremi Janatha Viyaparaya , “Patriotic Popular Front”) and the IUSF ( Inter-University Students Federation ) systematically carried out terrorist attacks against government politicians , the police and the security forces. They were supported by a network of JVP sympathizers within state institutions and also in the army. The JVP obtained their weapons through robberies on army bases. On August 18, 1987, there was a hand grenade attack at a UNP parliamentary meeting in the parliament building in Colombo. The aim of the attack was apparently the simultaneous assassination of President Jayewardene and Prime Minister Premadasa. There were two fatalities, but the President and Prime Minister were unharmed. A general climate of violence and lawlessness spread against the backdrop of the decline of governmental authority and public order. Old conflicts were increasingly carried out outside of the law and the number of murders increased significantly. Due to the loss of state order, public transport and the supply of gasoline, food and consumer goods collapsed in many places. Schools, universities, factories and other workplaces remained closed. People who could afford it temporarily went to safe foreign countries and the tourism industry came to a standstill.

UNP politicians were initially unsure how to counteract the uncontrolled violence. The JVP also did not openly admit to the attacks. Observers have suspected that the opposition SLFP or some of its supporters played a certain role in the acts of violence by allowing them to happen passively or possibly partially actively supporting them. Some SLFP politicians, such as Anura Bandaranaike, spoke more or less openly in favor of a merger or cooperation with the JVP. Other armed organizations followed, such as the government's Special Task Force (STF), the Green Tigers , which euphemistically referred to thugs of UNP supporters, and an opaque organization called the People's Revolutionary Red Army in the middle of the election campaign (PRRA). The disputes were conducted with the greatest ruthlessness on both sides. The cases of killings or defacement of killed opponents by means of burning car tires ( "necklacing" ) also became notorious abroad .

Election campaign and election campaign goals

Three candidates were accepted for election: Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa ran for the UNP, party leader and ex-prime minister Sirima Bandaranaike ran for the opposition Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) , and Ossie Abeyagoonasekera stood as the third candidate for the Sri Lanka Mahajana Party (SLMP). In the run-up to the election it was speculated that the 81-year-old Jayewardene might want to apply for a third term. The constitution stipulated that the term of office was limited to two terms, but the ruling UNP had a 5/6 majority in parliament, which would have enabled it to adopt a constitutional amendment with a two-thirds majority. However, under the influence of his advisors, Jayewardene decided not to run again and voted for Prime Minister Ranasinghe Premadasa as a candidate. This was officially proclaimed a UNP presidential candidate at a UNP party meeting in Sugathadasa Stadium in September 1988. On September 20, 1988, Anura Bandaranaike announced that Sirimavo Bandaranaike (his wife and the SLFP chairwoman) would be a joint candidate for the Democratic People's Alliance (DPA), a multi-party alliance . This alliance should also include the JVP. Ultimately, a five-party electoral alliance came about under the leadership of the SLFP, but this did not include the JVP. Despite the advances made by the SLFP against the JVP, the election campaign events in Bandaranaikes were repeatedly disrupted by actions by the JVP, with some SLFP employees also perishing.

In contrast to President Jayewardene, Premadasa also avoided calling the JVP by name during the election campaign as the perpetrator and instigator of the violence. Perhaps he was hoping for some kind of truce with the JVP - a hope that was not fulfilled.

The JVP declared the elections illegal and threatened reprisals if they participated. The declared aim of the JVP was the withdrawal of the IPKF and the resignation of President Jayewardene and his government even before the election, as a prerequisite for a subsequent “free and fair” election. The LTTE called for the withdrawal of Indian troops and called on the Tamils in the north to boycott the elections.

All three candidates promised in the election campaign to restore law and order and to ensure that the IPKF withdrew. Premadasa underlined the supposed successes of his more market economy policy - more jobs, consumer goods, etc. - compared to the years of the “socialist shortage economy” during the Bandaranaike government 1970–1977. He promised a program to fight poverty and social action for the poor. Bandaranaike criticized the high inflation, which the government had not got under control, the rise in unemployment since 1982, and accused the government of doing nothing for the poor. The third candidate, Ossie Abeyagoonasekera, represented a state economic and dirigistic economic program.

The Ceylon Workers' Congress , the largest Indian Tamil party, supported the UNP. The Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) and the Eelam People's Revolutionary Liberation Front (EPRLF) made election recommendations for the SLMP candidate Abeyagoonasekera.

Regular opinion polls were not possible due to the collapse of public order. Quite a few observers expected the opposition to win the election. According to press reports, 36 ministers and UNP members of parliament were out of the country at the time of the election - possibly because they expected a victory for the opposition and subsequent repression.

The resources in the election campaign were very unevenly distributed. The UNP government used the government apparatus (vehicles, press, radio, etc.) to promote its policy. The opposition was much more hindered by the supply and communication bottlenecks than the ruling party.

| Name of the candidate | Political party | Abbreviation | Election symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ranasinghe Premadasa | United National Party | UNP | elephant |

| Sirimavo Bandaranaike | Sri Lanka Freedom Party | SLFP | hand |

| Ossie Abeyagoonasekera | Sri Lanka Mahajana Party | SLMP | eye |

Results

Overall result

Of the 9,375,742 registered voters, 5,186,223 (55.32%) took part. 5,094,778 votes (98.24%) were valid and 91,445 (1.76%) were invalid.

| Name of the candidate | Political party | Absolutely | Votes in% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranasinghe Premadasa | UNP | 2,569,199 | 50.43% | |

| Sirimavo Bandaranaike | SLFP | 2,289,860 | 44.95% | |

| Ossie Abeygunasekara | SLMP | 235.719 | 4.63% | |

| Valid votes | 5,094,778 | 100.0 | ||

Results by constituency

Premadasa won the majority in 16 constituencies and Bandaranaike in 6.

| Constituency | Premadasa (UNP) in% |

Bandaranaike (SLPF) in% |

Abeygunasekara (SLMP) in% |

Valid votes in% |

Invalid votes in% |

Electoral participation in% |

Registered voters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo | 49.14 | 46.23 | 4.63 | 98.49 | 1.51 | 68.57 | 1,088,780 |

| Gampaha | 48.08 | 48.83 | 3.09 | 98.64 | 1.36 | 76.12 | 969.735 |

| Kalutara | 46.74 | 49.57 | 3.69 | 98.23 | 1.77 | 64.76 | 570.118 |

| Mahanuwara | 54.88 | 43.65 | 1.47 | 98.57 | 1.43 | 68.88 | 628.240 |

| Matale | 57.85 | 40.37 | 1.77 | 98.29 | 1.71 | 30.28 | 214.938 |

| Nuwara Eliya | 62.15 | 35.98 | 1.87 | 98.19 | 1.81 | 79.96 | 229,769 |

| bile | 44.62 | 53.09 | 2.29 | 98.43 | 1.57 | 49.78 | 571,303 |

| Matara | 42.93 | 54.30 | 2.76 | 98.14 | 1.86 | 23.84 | 451.934 |

| Hambantota | 49.62 | 47.39 | 2.98 | 95.56 | 4.44 | 29.43 | 295.180 |

| Jaffna | 28.03 | 36.82 | 35.15 | 93.38 | 6.62 | 21.72 | 591,782 |

| Vanni | 55.78 | 25.77 | 18.45 | 96.40 | 3.60 | 13.79 | 142,723 |

| Batticaloa | 50.99 | 17.38 | 31.63 | 95.91 | 4.09 | 58.48 | 215,585 |

| Digamadulla | 50.77 | 43.78 | 5.45 | 98.04 | 1.96 | 72.89 | 265,768 |

| Trincomalee | 45.70 | 36.81 | 17.49 | 98.38 | 1.62 | 53.81 | 152.289 |

| Kurunegala | 51.12 | 46.89 | 1.99 | 98.91 | 1.09 | 50.05 | 784.989 |

| Puttalam | 55.89 | 42.28 | 1.83 | 98.70 | 1.30 | 71.23 | 319.003 |

| Anuradhapura | 42.94 | 55.15 | 1.91 | 98.36 | 1.64 | 40.36 | 334.074 |

| Polonnaruwa | 55.54 | 42.45 | 2.01 | 97.62 | 2.38 | 29.73 | 163,741 |

| Badulla | 60.08 | 37.36 | 2.56 | 97.62 | 2.38 | 41.80 | 329,462 |

| Moneragala | 63.21 | 34.18 | 2.61 | 96.91 | 3.09 | 17.01 | 161,927 |

| Ratnapura | 51.75 | 45.81 | 2.44 | 98.84 | 1.16 | 77.23 | 457.224 |

| Kegalle | 57.17 | 40.54 | 2.35 | 98.48 | 1.43 | 68.55 | 437.178 |

| total | 50.43 | 44.95 | 4.63 | 98.24 | 1.76 | 55.32 | 9,375,742 |

Voting cards

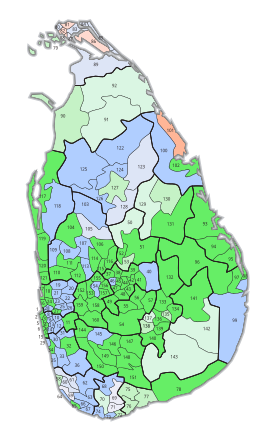

- Majorities according to constituencies and voting districts, as well as voter participation

Majorities in the 160 voting districts: Premadasa (UNP), participation> 35% Premadasa (UNP), participation 15–35% Premadasa (UNP), participation <15% Bandaranaike (DPA), participation> 35% Bandaranaike (DPA), participation 15 -35% Bandaranaike (DPA), participation <15% Abeyagoonasekera (SLMP), participation> 35% Abeyagoonasekera (SLMP), participation 15–35%

Development according to the choice

Due to the tense security situation and the collapse of public order, the turnout was very low at 55.32%. In the two previous presidential elections it was over 80%. Premadasa won the election just ahead of Bandaranaike. Analysis of the election results showed that the UNP won more votes than the SLFP among religious minorities (Christians and Muslims). The latter, however, was more successful with the Sinhala Buddhist majority population. The turnout in the Tamil north was consistently low. After Premadasa's election victory became clear, violence flared up again. In the two weeks following election day, a total of 417 politically motivated murders occurred. In an attempt to de-escalate and normalize, the new President Premadasa lifted the previous state of emergency on January 13, 2019 and ordered the release of 1,500 imprisoned “subversive” suspects. After that, the security situation calmed down increasingly. However, the south only came to rest after the complete suppression of the JVP uprising and the death of the JVP rebel leader Rohana Wijeweera on November 13, 1989.

Individual evidence

- ↑ SWR de A. Samarasinghe: Sri Lanka in 1983: Ethnic Conflict and the Search for Solutions . In: Asian Survey . tape 24 , no. 2 , February 1984, p. 250-256 , JSTOR : 2644444 (English).

- ↑ a b Ralph R. Premdas, SWR de A. Samarasinghe: Sri Lanka's Ethnic Conflict: The Indo-Lanka Peace Accord . In: Asian Survey . tape 28 , no. 6 , June 1988, pp. 676-690 , JSTOR : 2644660 (English).

- ↑ a b c Vasantha Amerasinghe: Sri Lankan Presidential Election: An Analysis . In: Economic and Political Weekly . tape 24 , no. 7 , February 18, 1989, p. 346-350 , JSTOR : 4394399 (English).

- ↑ Features: How JRJ and the UNP top rung escaped death: The day Parliament was bombed. Sunday Island (Sri Lanka), September 24, 2006, accessed November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Mick Moore: Thoroughly Modern Revolutionaries: The JVP in Sri Lanka . In: Modern Asian Studies . tape 27 , no. 3 , July 1993, p. 593-642 , JSTOR : 312963 (English).

- ^ Sri Lanka: The Years of Blood. srilankabrief.org, April 24, 2014, accessed October 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Maheshi Anandasiri: Easter Day 2019, Sri Lanka: The questions without answers. DailyFT, May 11, 2019, accessed October 27, 2019 .

- ^ Rajesh Venugopal: Sectarian Socialism: The Politics of Sri Lanka's Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) . In: Modern Asian Studies . tape 44 , no. 3 , 2010, p. 567-602 , doi : 10.1017 / S0026749X0900402 (English, pdf ).

- ↑ Thirty one years ago in 1988, it was 'Presidential Election year', similar to now. Ceylon Today, September 3, 2019, accessed November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ SWR de A. Samarasinghe: Sri Lanka's Presidential Elections . In: Economic and Political Weekly . tape 24 , no. 3 , January 21, 1989, pp. 131-135 , JSTOR : 4394274 (English).

- ↑ Shelton U. Kodikara: The Continuing Crisis in Sri Lanka: The JVP, the Indian Troops, Tamil and Politics . In: Asian Survey . tape 29 , no. 7 , July 1989, p. 716-724 , JSTOR : 2644676 (English).

- ^ Rajan Hoole: The Year 1988: The Presidential Election Campaign. Colombo Telegraph, November 15, 2019, accessed November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c Presidential Election Results: Results of Presidential Election - 1988. Sri Lankan Electoral Commission, accessed on August 8, 2019 (English).