Salome Alexandra

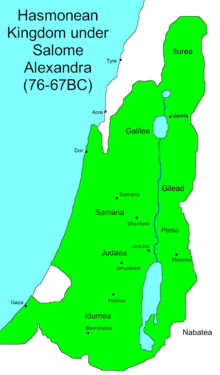

Salome Alexandra (born 140 BC (?); Died 67 BC ) was Queen of Judea from 76 BC. BC to 67 BC She was the wife and successor of the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannäus .

Alexandra as the wife of Jannaios

Nothing is known about their origins and families prior to their marriage. According to Flavius Josephus , she died at the age of 73, so it would be 140 BC. Born in BC. In any case, as a relatively mature woman, she seems to have married the much younger Alexander Jannaios . From a statement made by Josephus one can conclude that at this point in time she already had a ten-year-old son (who later became high priest John Hyrcanus II ), but here one usually assumes that Josephus is mistaken.

As probably all Hasmoneans since John Hyrcanus I , Alexandra had a Greek and a Hebrew name. The form of the Hebrew name is still controversial, the evaluation of Talmud and Qumran sources allow the possibility that your Hebrew name was Shelamzion. If this were the case, Shelamzion Alexandra, the wife of Alexander Jannaios, would probably not be the wife of Aristobulus I , whose Hebrew name is said to have been Salina (Josephus Antiquitates Iudaicae 13, 320). Since Alexandra did not mint any coins, it is not certain whether she, as queen, like her late husband, used both names as sovereign names (Hyrcanus I only used the Hebrew name on coins).

After the death of Aristobulus I in 103 BC After only one year of reign, Alexandra became queen at the side of Alexander Jannaios. Josephus assumes that Alexandra was previously the wife of Aristobulus and was now in a position to determine Jannaios as the new king ("she appointed Jannaios, also called Alexander, as king"). If that is true, one can imagine a leviral marriage that would have legitimized the new king Jannaios. Josephus does not say so, however, and some researchers are of the opinion that this is another Alexandra.

Accession to the throne

After 27 years of reign, Alexander Jannaios died. He did not name one of his sons, but his wife as successor; According to Josephus, he made her promise to end the longstanding conflict with the Pharisees . So it was made in 76 BC. First and only queen of Judea . Her son John Hyrcanus II took over the office of high priest , since this was impossible for Alexandra as a woman. The union of high priesthood and kingship in one person, which had existed since Aristobulus I, was therefore dissolved under Alexandra.

Foreign policy

Josephus reports that Alexandra subsequently preferred the Pharisees to the Sadducees , which had set the tone until then . They even took over the actual power in the state and “did not differ in anything from autocratic rulers”. The representation is not impartial, however, because Josephus describes himself as a Pharisee and leaves no doubt that, in his opinion, a woman is incapable of rule. Alexandra's foreign policy is only portrayed episodically. She appointed her younger son Aristobulus II as a military leader and charged him with guarding numerous fortresses. She then sent him on a - according to Josephus unsuccessful - train against Damascus, which was occupied by Ptolemy, the son of Mennaios.

The greatest threat to Judea at this time no longer came from the Seleucids , but from Tigranes II , who occupied the remains of the Seleucid Empire until the Roman intervention. Alexandra is said to have prevented him from conquering Judea "through contracts and gifts". This has often been understood to mean that Alexandra had become the Tigran's vassal. According to Josephus, Alexandra benefited from the fact that Tigranes was busy with the siege of Ptolemais , which he then took due to Lucullus' invasion of Armenia in 69 BC Had to cancel. It can be assumed that Alexandra's position towards Tigranes was not as weak as Josephus suggests.

Death and Succession

Alexandra's domestic political decisions are hardly known. In retrospect, the most important thing appears to be the treatment of her two sons. While Hyrcanus II was planned to be high priest and, apparently, a successor, Aristobulus II was only left with the position of military leader. This decision turned out to be fatal. Alexandra fell ill and her younger son Aristobulus first brought the fortress Agaba and within a short time 21 other fortresses into his hand. When Alexandra died, a civil war began between the brothers Aristobulus and Hyrcanus, which began in 63 BC. Led to Rome intervening in the conflict, which ultimately brought the end of independent Jewish statehood with it.

Alexandra in Jewish memory

In addition to Josephus, who rejects the royal rule of a woman in Judea and therefore influenced the memory of Salome, there are rabbinical sources that - partly inspired by Josephus - report alleged events from the time of Alexandra. They are usually not used to reconstruct the history of events, but are interesting as documents relating to the history of reception.

Under their government, the presidency of the High Court went to the Pharisees under Shimon ben Shetach , whose (political) connection with Alexandra is said to have been so close that it was later assumed that he was Alexandra's brother. The Alexandrian scholar Juda ben Tabbai became chairman of the high council ( Nasi ) , although this office had been exercised by the high priest until then . After Judah ben Tabbai had resigned from his position as chairman of the council because of a judicial murder of a false witness for which he was responsible, the chairmanship passed to Simon ben Schetach.

Some of the laws that are still relevant today are traced back to the time of Alexandra in these sources, in particular the marriage law (ensuring the maintenance of a divorced woman) and the introduction of religious schools. In the background there is possibly the report of Josephus, according to which Alexandra was "God-fearing" and listened to the Pharisees who, according to rabbinical self-portrayal, were the forerunners of rabbinic Judaism. At that time , the annual temple donation of half a shekel mentioned in Exodus is said to have been introduced for male adults over the age of 20, which appears in the New Testament as a temple tax . This temple donation or tax was levied not only by the Jews of Judea but also by the Jews of the Diaspora and formed the basis for the very substantial annual income of the Jerusalem temple until its destruction.

There have been various attempts in research to prove Alexandra as the historical model for the protagonist of the book Judit , but this hypothesis has not been able to prevail.

In Jewish memory, the nine-year rule of Alexandra is considered to be one of the most peaceful and happiest periods in Israel's history. Centuries later, the authors of the Babylonian Talmud wrote :

- The wheat grains were the size of a bean, the barley grains the size of an olive, and the lentils resembled gold denarii; the scribes collected this grain and saved samples of it to show future generations the consequences of sinfulness. ( Ta'anit 23a )

literature

- Kenneth Atkinson: The Salome No One Knows , In: Biblical Archeology Review July / August 2008 (English)

- Louis Ginzberg : Alexandra. In: Isidore Singer (Ed.): Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, New York 1901-1906.

- Heinrich Graetz : History of the Jews , Volume 3.1, Chapter 7.

- Tal Ilan: Silencing the Queen. The Literary History of Shelamzion and Other Jewish Women. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-16-148879-2

- Samuel Rocca: The Book of Judith, Queen Sholomzion and King Tigranes of Armenia: A Sadducee Appraisal. In: Materia Giudaica 10 (2005), pp. 85-98.

- Christiane Saulnier: L'aîné et le porphyrogénète. Recherche chronologique sur Hyrkan II et Aristobule II. In: Revue Biblique 97 (1990), pp. 54-62.

- Ernst Baltrusch: Queen Salome Alexandra (76-67 BC) and the constitution of the Hasmonean state . In: Historia 50 (2001), 163-179.

- Ulrich Wilcken : Alexandra 2 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 1, Stuttgart 1893, column 1376.

Web links

- Susanne Luther: Salome Alexandra (134-67 BC). In: Michaela Bauks, Klaus Koenen, Stefan Alkier (Eds.): The Scientific Biblical Lexicon on the Internet (WiBiLex), Stuttgart 2006 ff.

- Queen Salome Alexandra , entry in Chabad.org Gallery of Our Great (English)

Remarks

- ↑ According to Josephus Antiquitates Iudaicae 15, 178, Hyrcanus II was named in 31 BC. Executed at the age of over 80; so it would have to be at least 110 BC. Have been born in BC. Josephus nevertheless assumes that Hyrcanus II is like Aristobulus II the son of Alexandra and Jannaios; then his figures would not be correct. On the Saulnier problem, see the bibliography.

- ↑ Josephus Antiquitates Iudaicae 13, 320. The woman's name is there in some manuscripts "Salome", in others "Salina"; in any case she is "called Alexandra by the Greeks".

- ↑ Josephus Antiquitates Iudaicae 13, 409. Cf. also Bellum Iudaicum 1, 112: "She herself ruled the others, but the Pharisees ruled her".

- ↑ Josephus Bellum Iudaicum 1, 116. Cf. Antiquitates Iudaicae 13, 419, where there is no mention of contracts.

- ↑ For the distribution of offices see article on bmv.org.il

- ↑ Josephus Bellum Iudaicum 1, 111.

- ↑ See last Rocca in the bibliography.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Alexander Jannäus |

Queen of Judea 76–67 BC Chr. |

Aristobulus II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Salome Alexandra |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Shel-Zion; Shalmonine; Shalmzi; Shawmza; Schlamto; Shelf Zion |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | jewish queen |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 140 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 67 BC Chr. |