Scarabaeus variolosus

| Scarabaeus variolosus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Scarabaeus variolosus |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Scarabaeus variolosus | ||||||||||||

| Fabricius , 1787 |

Scarabaeus variolosus is a beetle from the family of scarab beetles and the subfamily of Scarabaeinae . The genus Scarabaeus is represented in Europe with eleven species . The species Scarabaeus variolosus belongs to the subgenus Ateuchaetus of the genus Scarabaeus .

Comment on the name

The species was first described by Fabricius in 1787 under the name that is still valid today. The short description contains the sentence punctis impressis variolosis (Latin with indented scar points ). This explains the species name variolosus (Latin scarred ), which refers to the puncturing reminiscent of smallpox or peeling scars . However, such puncturing can also be found in Scarabaeus cicatricosus and partly in Scarabaeus semipunctatus . Scarabaeus cicatricosus was separated from Scarabaeus variolosus in 1846 by Lucas . Sturm translates Scarabaeus variolosus with ' pear-scarred pill beetle' , tanks with 'the poken-like dung beetle'. At Brehm , the beetle is called the 'pockmarked pill turner'. Klausnitzer names the two species Scarabaeus variolosus and Scarabaeus cicatricosus with the name 'pockmarked Scarabaeus' .

The word Scarabaeus is already used by Pliny the Elder around 700 in his Naturalis historia . It stands there for the Greek word κολεόπτερος (Koleopteros), which was coined by Aristotle, for the insects with winged wings . In the volume Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum of his Historia animalium , which was revised by Gessner and only published in 1634, but which is based on an earlier, unpublished work, it is expressly mentioned in Chapter 11 that the Latin word Scarabaeus corresponds to the German word Käfer . In the Historia animalium by Aldrovandi in the 7th volume of 1602, however, the author points out that he does not designate all beetles as Scarabaeus . From the figure and the description of 36 beetles in six panels show that Aldrovandi at least several stag beetles , scarab beetles , longhorn beetles , ground beetles counted and some aquatic beetles to the scarabs. When the binomial nomenclature was introduced in 1758, Linné named Scarabaeus as the first genus of beetles and included 63 species, which essentially comprised the scarab beetles and stag beetles known at the time , namely the beetles whose antennae (horns) end in a split (leafed) club (Antennae clavatae capitulo fissili). Among these species there is also a species of the genus, Scarabaeus sacer , in today's much narrower cut.

The subgenus Ateuchetus was established by Bedel in 1892 . Bedel does not explain the name. According to Schenkling , he is from old Gr. ατεύχητος "ateuchetos" derived for "unarmed, unarmed" and refers to the fact that the males of the species of this subgenus do not wear a horn or hump on their heads.

The beetle has also been described as Ateuchus variolosus . The genus name Ateuchus means the same as the subgenus name Ateuchetus .

Olivier describes the species Scarabaeus semipunctatus under the name Scarabaeus variolosus .

In various places on the Internet, Scarabaeus variolosus MacLeay is listed as a synonym for Scarabaeus cicatricosus in 1821 . However, MacLeay does not provide an initial description in 1821, but refers to the first description of Scarabaeus variolosus by Fabricius. In addition, Scarabaeus cicatricosus was only separated from Scarabaeus variolosus in 1846 . From MacLeay's description it is not clear whether he describes S. cicatrosus or S. variolosus . The distribution area given by MacLeay corresponds to the distribution area of S. variolosus , which, however, overlaps with that of S. cicatricosus in North Africa. Fabricius 1787 can only have meant Scarabaeus variolosus in today's sense with South Tyrol as Patria indication .

Properties of the beetle

The beetle is black and moderately shiny. It becomes fifteen to twenty-five millimeters long. The body is wide and relatively flat, a little over 1.5 times as long as it is wide.

The tightly wrinkled head shield is four-toothed, the laterally adjoining part of the cheeks has a further tooth on each side, so that the head is reinforced with six forward-facing teeth. The forehead is dotted on the sides and smooth in the middle. The eyes are completely divided into one half on the underside of the head and one on the top of the head (Fig. 2). The nine-part antennae end in a three-leaved, spherical club.

The pronotum is wider than it is long, the back corners rounded, the front edge behind the head cut out shallow. The side edge of the pronotum is covered with pointed teeth (Fig. 3 above), which are particularly strong in the third and fourth fifth of the edge. Shortly before the edge of the base of the pronotum runs a series of points, each of which has a hair bristle (pore points Fig. 3 right). However, this row of points is not separated from the pronotum by a furrow, as in Scarabaeus pius . The pronotum and the elytra are provided with remarkably large and very flat pore points. These are very different in frequency in different specimens, are distributed irregularly on the pronotum, and are arranged in rows on the elytra. Due to a different microstructure, they appear more matt, and due to soiling they are often more distinct in color.

The pronotum and elytra close together and completely cover the small label .

The elytra are very finely striped, the spaces in between are flat and irregular with flat, large, matt dots. The lateral edges of the wing covers are almost parallel, only in the last quarter they are rounded. They end at right angles to each other and leave the pygidium uncovered.

The front and rear hips are touching, the middle hips are apart (Fig. 1 right).

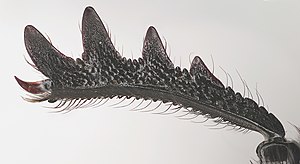

The front legs end at the front with a short end spike, the rails have four strong teeth on the outside, the outer edge is serrated in between. The inner edge of the front rails is also clearly indented. Near the base the serration disappears on the inner edge, on the outer edge it merges into notches. Anterior tarsi are absent (Fig. 5). The rails of the other legs also end in an end pin. The rear rails do not taper as in the subgenus Scarabaeus behind the turning of the tarsi to the width of the terminal mandrel, but they are slightly truncated at the level of the turning of the tarsi. This creates a square insertion surface for the tarsi, which is framed with a bristle ring and at the lower inner corner of which the slightly movable end spine arises (Fig. 7). The claws are not significantly shorter than the end bristles of the last tarsal segment (Fig. 4). Claw length and deflection of the hind tarsi characterize the subgenus Ateuchus . The thighs of the hind legs are not cut out broadly flat on the back as in the similar Scarabaeus cicatricosus , but mostly slightly convex (Fig. 6).

biology

Scarabaeus variolosus is diurnal, not crepuscular. An evaluation of the find data from various countries provides heights between 180 m and 580 m for the sites.

The species of the genus Scarabaeus and some related genera ( Gymnopleurus , Sisiphus , Kheper ...) use fresh dung from various grazing animals to make balls (pills) that are larger than the beetle and that are rolled away by the beetle from the place of manufacture. The beetles are therefore called pill-twisters or pill-curlers. Then the pills are buried. This prevents their dehydration. The detailed investigations into the behavior of six European species of the genus Scarabaeus including Scarabaeus variolosus show the following common behavioral characteristics:

The beetles reproduce in spring, the fully developed next generation appears in autumn and overwinters in the ground. Accordingly, the beetles are found most frequently in spring and more often in autumn. In cool weather the beetles stilt around awkwardly, in hot weather they are quick and very active. When flying, they generate a deep hum. They fly with the deck wings closed. Fresh manure is smelled by flying beetles and can attract many beetles. The beetles land near the excrement, run towards it and, after checking the quality of the manure, start making a pill.

Making the pill

Both males and females are capable of making pills. This activity is also called 'baking'. There are two different types of production.

If voluminous manure masses are available (such as a cow dung), the beetle uses the head shield as a spade and presses the part underneath it with its front legs under its chest, and pushes the material in front of the head shield outwards. It rotates in a circle, creating a moat. So he works his way down, with the mass lying below him growing from a segment of a sphere to a sphere that is kneaded with the hind legs so that it shows almost the final radius from the beginning. Finally he cuts off the remaining connection at the deepest part to the surrounding manure mass and levered the finished ball upwards.

If the available manure consists of small parts (e.g. manure that crumbles into individual bales), two parts are gathered together, protruding parts are cut off with the head shield, and the rest is kneaded (baked) under the breast. This process is repeated until the initially small pill has grown into a ball of the desired size.

The finished pill only deviates from the spherical shape if parts of the dung used have already dried out to such an extent that they can no longer be kneaded (Fig. 8) or if the competition is so great that the beetle cannot complete its work undisturbed can.

Two types of pills are made, food pills and brood pills. The food pills are eaten by the beetle itself, the breeding pills are converted into breeding pears after they are buried. A beetle of the next generation develops in each of these. Feed pills and brood pills initially only differ in that any available herbivore dung is used quite indiscriminately for feed pills, and human droppings are also gladly accepted. For brood pills, however, sheep droppings are clearly preferred.

Transportation of the pills

Males and females can carry a pill on their own. The beetle has lowered its head and its hind legs are gripping the ball. The beetle walks backwards with its front legs and the dung ball is rolled further with its hind legs.

Same-sex beetles and beetles of other species are chased away during the production and transport of the pills, and the attacker can emerge victorious from the dispute. The dispute is usually resolved after a few seconds, as the attacker is levered out by the ball owner with the head shield and thrown away. If the attacker is not deterred immediately, the opponents stand up towards each other and try to throw the opponent on his back. The winner uses his front legs to squeeze the loser's chest and front legs together. Often, while the owner and attacker argue violently, the bullet is stolen by a third beetle.

A partner of the opposite sex of the same kind is tolerated, but the couple can only stay together through the pill. If such a random pair has formed, a division of roles immediately occurs when the ball is transported: the male continues to roll the pill, walking backwards with his hind legs, the female follows crawling forward at a distance of about two centimeters. If another female approaches, the male will not be disturbed, the females will fight with each other and the winner will then hurry after the ball that the male has meanwhile carried on. If, on the other hand, a male approaches the pair, the males fight for possession of the ball and the female accepts the winner as the carrier of the ball. Only if the male's fight lasts too long does the female's rolling instinct break through and she transports the dung ball on by herself. Even if the male is prevented from further transport by obstacles, the female can get to the ball and perhaps climb it. However, once the male has found a way to move the pill further, he will not be considerate of the female, possibly knocking her off the ball, or simply rolling her away with the ball.

If a beetle is prevented from rolling by obstacles on its way, it climbs the ball to orientate itself, but the following transport attempts are not purposeful, but are based on the principle of trial and error . Transporting it and trying to overcome obstacles can take hours.

Burying the pills

It could not be observed that a particularly favorable place for burial is chosen. Often some point in front of an obstacle is chosen which, after several attempts, proves to be insurmountable for the beetle. Both males and females can bury a dung ball on their own. In the case of couples, the male determines where the ball is buried and takes on most of the work, while the female remains largely passive (Fig. 8). If the male works too slowly, the female can steal away with the ball.

There are two methods of digging, both of which can be used by the same individual.

In the first method, the beetle crawls under the ball and undermines it by pushing up excavated material on all sides of the ball. This causes the ball to sink into the ground. The material that was pushed up collapses above it. Additional material that is pressed up increasingly forms a rounded, flat hill.

In the second method, the beetle digs a passage in the ground a short distance from the ball of excrement. The excavated material is pushed away in one direction, creating a furrow bounded by two side walls. If the passage is big enough, the beetle comes out without excavation material and transports the ball into the cave. This can be done in a number of ways. If the bullet is within reach, the beetle grabs it with its front legs and pulls it into the cave. If it is further away, then he transports it backwards into the cave entrance, as already described. Now he pushes the ball with his head into the passage or he works his way past it and pulls it from the inside into the dug passage. With this method, too, the duct is then driven further deeper and the ejection piles up around the former entrance. The uneven storage of the excavation testifies to the method used to bury the dung ball even after the beetle and pill disappeared.

Transformation from the brood pill to the brood pear

Food pills are usually eaten from below by the beetle (male or female or both together) after they are buried.

Brood pills are only produced by females, transported and on average buried deeper than the food pills. Then they are transformed into brood pears. Four noticeable changes can be identified:

- The spherical shape becomes a pear shape: the hardly smaller sphere has a small sugar-hat-shaped hill on the highest point, which is hollowed out inside in the form of a truncated pyramid (egg chamber).

- All dirt that stuck to the surface of the ball during transport is removed.

- The consistency of the brood pear is significantly finer and more elastic than that of the brood pill.

- The brood pear no longer smells of manure.

The female effects this transformation by picking the brood pear into small pieces, gnawing them further, forcing them with secretions and then baking them back together again. Presumably, germs are also killed, in any case you won't find any moldy breeding pears. However, nothing is diverted from the beetle as food for itself. The new sphere is built up in concentric layers. The egg chamber is baked on at the highest point of the ball. The breeding pear lies in a spacious cave that is roughly the shape of a pear and in which the female can move next to the pear.

A female usually produces fewer than six brood pears. It takes about 12 hours to produce a brood pear from a brood pill.

Dependence on sexual maturity

Investigations on other types of pill-twister show that the behavior is partly determined by the degree of maturity of the beetle's gonads. For example, males become more aggressive when they reach sexual maturity. The distribution of roles between the sexes in the manufacture, transport and burying of the pills is also influenced by the degree of maturity of the gonads.

- The rolling and burying of pills by solo males serves to ensure that the pill is completely and almost continuously eaten by the male for several days after it has been buried. The digested food is excreted almost continuously as a continuous thread of feces, the length of which is ten times the length of the body. Only the smell of fresh dung penetrating from the outside can induce the male to break off the meal and dig up to make a new dung pill.

- The rolling and burying of pills by solo females before reaching sexual maturity also serves to nourish the beetle. It corresponds to the ripening .

- The rolling and burying of pills by solo females after reaching sexual maturity is used to make brood pears.

- The rolling and burying of pills by a couple is interpreted as a prenuptial offering. Both beetles consume a small part of the pill. Then mating takes place. The male then digs himself back to the surface and leaves most of the pill to the female as food. Whether the female is mated by different males or whether all offspring result from one mating may depend on the food available.

development

The female sticks a single egg to the top of the cavity of the egg chamber. In addition, a chimney for ventilation is built vertically upwards from loosely layered grains of sand and dung particles. After that, the female will forever leave the cave in which the breeding pear lies.

When the young larva hatches from the egg after a short time, it eats its way into the pear neck. After the first molt, the larva first eats its way down, then hollowing out the entire breeding pear. The wall of the cavity is continuously smoothed by the larva by evenly smearing its excrement on the wall with a secretion. When the cavity is enlarged, it eats not only new material but also its own droppings. She also improves the usability of her diet through extraintestinal digestion by regularly vomiting up digestive juices.

If the wall of the brood pill is damaged when the cavity is enlarged, the larva immediately closes the hole with its own feces and a sticky secretion. Pupation takes place after about a month. When the pupa is resting, the insect lies on its back on the floor of the brood bulb, which is reduced to a thin wall. The young beetle hatches after about another five weeks. This is colored after a further week and then breaks through the brood pear. In late summer it burrows to the surface of the earth.

larva

The structure of the larva is extremely adapted to its way of life (Fig. 9). The larva is blind, the function of the legs is no longer locomotion, and the body shape is greatly modified.

The forelegs are drawn to the mouth parts. They serve to feed pieces of food to the mouth parts. The middle and rear legs are also facing forward. They are used to support against the wall of the spherical cavity in which the larva lives. Movements within the cave are limited to the fact that the body can rotate in all directions. These movements are brought about by the peristaltic enlargement or reduction of the large hump and an abdomen that ends like a stamp. The latter serves as an auxiliary foot , similar to a follower .

The hump houses a large sac-like protuberance of the midgut.

distribution

Within Europe, the beetle is found in the south, but not in the southwest. Its occurrence in southern France is doubtful. The species is reported from Sardinia , Italy with Sicily and Malta . In the Balkans , the northern limit of distribution runs through Slovenia , Croatia , Serbia , Bulgaria and European Turkey . To the east, the distribution area reaches Asian Turkey. South of the Mediterranean , the beetle is known from Algeria , Morocco and Tunisia .

The beetle as an animal god

The ancient Egyptians worshiped the scarab as an animal god, a symbol of the sun god, who pushes the sun disk across the firmament and sinks with it into the underworld in the evening, only to emerge unchanged from the earth again. From pictures, sculptures and grave goods it can be seen that the Egyptians already perceived the beetle in its various species.

The prophet Ezekiel (Ezekiel) of the Old Testament tells of his vision of four four-winged cherubim ( etymologically related to the Egyptian word for beetles), all over their bodies ... full of eyes and moving the divine throne. The noise of the flight, the folding away of two of the four wings and the free movement in all directions are carried out. It is assumed that this vision is related to the worship of the sun god in the form of Scarabaeus variolosus , the top of which is also completely marked with 'eyes' is covered.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Scarabaeus variolosus from Fauna Europaea, accessed on Feb. 22, 2020

- ↑ Joh. Christ. Fabricius: Mantissa insectorum… Volume 1 Hafnia (Copenhagen) 1787 p. 16 No. 161 Scarabaeus variolosus

- ↑ PH Lucas: Histoire naturelle des animaux articulés - deuxième partie: insectes in Exploration scientifique de L'Algérie pendant les années 1840, 1841, 1842 - Sciences Physiques, Zoologie Paris 1849 p. 249 No. 660 Ateuchus cicatricosus

- ↑ Jacob Sturm: Illustrations for Carl Illiger's translation of Olivier's Entomologie or Natural History of Insects ... Nuremberg 1802 p. 94 Pill beetle

- ↑ Georg Wolfgang Franz Panzer: Fauna insectorum Germanicae initia, or, Germany's insects from 1796, Volume 12, Issue 67, No. 7, the poken-like dung beetle

- ↑ a b Brehms Tierleben - insects 3rd edition Vienna, Leipzig 1892, p. 86 illustration

- ↑ a b Bernhard Klausnitzer: Wonderful world of the beetles . Herder, Freiburg 1981, ISBN 3-451-19630-1 . P. 11

- ↑ Pliny the Elder: Naturalis historia 11th book on insects, chap. 34, 1st sentence English translation Latin edition

- ↑ Eduardo Wottono, Conrado Gesnero, Thomaque Pennio: Insectorum sive minimorum animalium theatrum definition Scarabaeus chap. XXI, p. 147 in Google Book Search

- ↑ Ulisse Aldrovandi: De animalibus insectis libri septem ... Bolognia 1602, chapter III p. 444 ff Internet edition

- ^ Carolus Linnaeus: Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis 1st volume, 10th edition, Stockholm 1758 p. 349: 385 genus Scarabaeus , p. 351: 347 No. 14 Scarabaeus sacer

- ^ A b Louis Bedel: Revision of the Scarabaeus palearctiques in L'Abeille - Journal d'Entomologie Volume XXVII, Paris 1890-1892 p. 283 Ateuchetus

- ^ A b Sigmund Schenkling: Nomenclator coleopterologicus 2nd edition, Jena 1922

- ↑ M. Olivier: Entomologie ou Histoire Naturelle des Insectes Coleoptères Tome I Paris 1789 not fully paginated, for the 3rd genus (Scarabaeus) p. 151 No. 184 Scarabaeus variolosus , associated illustration, panel 8, Fig. 60

- ^ A b W. F. Erichson: Natural history of the insects of Germany -1. Department: Coleoptera 3rd volume, 5th delivery Berlin 1847 as Ateuchus with key A, B3 p. 749, Ateuchus variolosus p. 753

- ↑ Scarabus variolosus Olivier, synonym

- ↑ Scarabaeus cicatricosus with synonym variolosus MacLeay 1821 from Fauna Europaea , accessed on March 21, 2020

- ↑ variolosus MacLeay 1821 Synonym cicatricosus from Iberfauna, accessed on March 21, 2020

- ^ WS MacLeay: Horae Entomologicae or Essays of the annulose animals Part 2, London 1821 p. 503 No. 18 Scarabaeus variolosus

- ↑ Jaques Baraud: Faune de France, Coléoptères Scarabaeoidea d'Europe Paris 1992

- ↑ Bruno Pittioni: The kinds of the subfamily Coprinae (Scarabaeidae, Coleoptera) in the collection of the Kgl. Naturh. Museum in Sofia . In messages from the Royal. Natural science institutes in Sofia - Bulgaria Volume XIII, Sofia 1940 p. 216 key

- ↑ Louis Báguena Corella: Scarabaeoidea de la fauna ibero-balear y pyrenaica Madrid 1967 p. 40 ff

- ↑ Jorge Lobo, Borislav Guéorguiev, Evgeni Chehlarov: The species of Scarabaeus Linnaeus (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidea) in Bulgaria and adjacent regions: Faunal review and potential distribution in Entomological Fennica 21 (4), S, 202 - 220, February 2011 p. 206

- ↑ Frequency curve of sightings of Scarabaeus variolosus by iNaturalist

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Hanns von Lengerken: Der Pillendreher (Scarabaeus) Leipzig-Wittenberg-Lutherstadt 1951 Reprint ISBN 3-89432-529-1

- ↑ Mario E. Favila, Maribel Ortiz-Dominguez, Ivette Chamorro-Florescano, Vieyle Cortez-Gallardo: Communication cimica y comportamiento reproductor de las escarabajos rodadores de estiércol (Scarabaeinae: Scarabaeini): Aspectos ecologicos y evolutivos y susibles aplication [1]

- ↑ Gonzalo Halffter, Violeta Halffter, Mario E. Favila: Food relocation and the nesting behavior in Scarabaeus and Kheper (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) Acta Zoologica mexicana (ns) 27 (2) pp. 305-324 (2011) ISSN = 0065-1737 [2]

- ^ JH Fabre: Souvenirs entomologiques - Études sur l'instinct et les moers d'insectes 5th series, Paris 1916 p.66 Larva of Scarabaeus sacer

- ↑ . Ivan Löbl, Daniel Löbl (Eds.): Catalog of Palaearctic Coleoptera, Vol. 3, Scarabaeoidea, Scirtoidea, Dascilloidea, Buprestoidea and Byrrhoidea - Revised and updated edition Leiden 2016 ISBN 978-90-04-30913-5 (hardbook), ISBN 978-90-04-30914-2 (e-book) distribution area S. variolosus p. 205 in the Google book search, distribution area S. cacatricosus p. 204

- ↑ Luther Bible: Ezekiel, especially chapter 1, verse 6 and chapter 10, verse 12

- ^ Charles L. Hogue: Commentaries in Cultural Entomology - 3. An entomological explanation of Ezekiel's wheels in Entomological News Vol 94, No. 3 New Jersey, USA, 1983 p. 74