Schoolchildren's Blizzard

The Schoolchildren's Blizzard (also Schoolhouse Blizzard ; German about Schoolchildren-Blizzard / Schoolhouse-Blizzard ) was a snowstorm ( Blizzard ) that hit the US states of the North American Great Plains on January 12, 1888 . Among the hundreds of deaths were many school children who were surprised by the blizzard in the school. They died after being sent home by teachers at the beginning of the blizzard, or froze to death when the heating material ran out in the simply built and poorly insulated schools.

The exact number of victims is unknown, but it is at least 200 people. Many of the victims died weeks after the blizzard as a result of their frostbite, which often required amputation of limbs. One of the heroines of the event was the teacher Minnie Mae Freeman Penney , who saved several students and who later u. a. a song was dedicated.

Weather conditions

On January 5th and 6th, a snow storm had hit the northern and central Great Plains. Not only did it bring very low temperatures from January 7th to 11th, it also left a thick blanket of powder snow . On January 11, a low-lying soil formed south-southeast of Alberta , which moved from there to Montana and northeast of Colorado , increasing in strength. It reached the southeastern Nebraska at 15 o'clock and at 23 o'clock southwestern Wisconsin . A warm front ran in front of the low pressure area , so that the temperatures initially rose significantly. For example, in Omaha, Nebraska, temperatures rose from −21 ° C on the morning of January 11th to −2 ° C on the morning of January 12th. The blizzard was triggered by an arctic cold front meeting warm, moisture-saturated air from the Gulf of Mexico . Within a few hours, the cold front caused a drop in temperature, during which the temperature fell from just under 0 ° C to −20 ° C and in some cases even −40 ° C. This drop in temperature was accompanied by a strong storm and snowfall. The storm reached Montana in the early hours of January 12, the Dakota Territory from mid-morning through early afternoon, and reached Lincoln, Nebraska at 3:00 p.m.

Effects

background

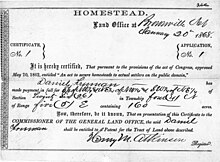

The areas particularly affected by the blizzard had not been populated by whites until the 1860s. Among other things, emigrants from Scandinavia who had emigrated mainly due to lack of land, as well as German-speaking Mennonites and Russian Germans had settled . The latter immigrated to Russia in the 18th century at the invitation of Catherine II . When the special status of these Russian Germans was gradually lifted after 1871 and they were subject to Russian military service from 1874 , a third of them emigrated. Many of them settled in the Great Plains area under the US Homestead Act . The Homestead Act did not allow contiguous villages, but only allowed for the establishment of widely spaced farms. The lack of wood meant that the settlers initially built mainly sod houses and at best simple, poorly insulated wooden houses. Wood was also missing as a heating material. Bison bones, cattle dung and, above all, bundles of hay were used for heating. The living conditions on the Great Plains were very harsh. Prairie fires, swarms of locusts and several very severe winters meant that many of the settler families were still living on the limit of existence at the time of the blizzard. This was also reflected in poorly insulated buildings and inadequate clothing.

Course of January 12th

The weather conditions on the morning of January 12th were unusually mild and sunny compared to the days before. Many parents took this as an opportunity to send their children back to school for the first time after several days. Many of the children had a mile-long walk to school that led them across the treeless prairie that offered few landmarks. Many farmers worked in the open air to do things that had fallen into disuse during the past cold days.

Numerous settlers have left eyewitness accounts of the outbreak of the blizzard, all of which show how quickly and with what force the blizzard fell upon them. An eyewitness, who was playing with other children in the schoolyard at that time, compared the approaching squalls with large bales of cotton that rolled towards them in a broad front. The children got back to the school house in time before the first gusts almost pushed the building off the foundation. In a school on the area of what is now the Rosebud Indian Reservation on the northern border of Nebraska, a teacher ran a few more steps out of the schoolhouse, then the gusts of wind caught them with such power that it was difficult for her to return to the schoolhouse. One of the most accurate descriptions of the oncoming blizzard comes from Sergeant Samuell Glenn, who worked for the then US Weather Bureau in Huron , South Dakota and was just reading the temperature on a flat roof:

- The air was completely still for about a minute and the voices and noises from the street below looked as if they were pushing up from a great depth. There was a strange silence over everything. For the next minute, the sky was completely obscured by a black cloud that a few minutes earlier had been on the western and northwestern horizon. The wind came […] was blowing in a south-westerly direction with such force that observers were in great danger. The air was immediately filled with snow as fine as sifted flour. The wind turned northeast, then northwest, and in three minutes the gusts had reached forty miles an hour. Five minutes after the wind turned, the outlines of objects fifteen feet away were no longer visible.

Many eyewitnesses described that the storm was preceded by a loud noise that reminded them of an approaching steam locomotive . Today's scientists attribute this volume to the fact that in the turbulence of the first gusts, the snow and ice already lying were torn up and finely ground. Visibility was drastically reduced immediately because the gusts of wind carried fine snow with them. Victims found later indicated that people caught outdoors by surprise were instantly disoriented. In Sioux Falls, for example, a frozen woman was found a few steps from her front door, who was still holding the front door key in her hand. Several survivors, who were surprised in the open air, said that they could only find the next building because they could cling to a sledge in the courtyard or a clothes line stretched across the courtyard. Others reported that particles of ice froze their eyelashes together and that a layer of ice formed on their face in minutes.

Teachers who were surprised by the blizzard with their students were faced with the choice of either sending the children home immediately or trying to stay with them in the school building. The wind immediately cooled the buildings and drove powder snow inside through cracks in the walls. In many schools there was not enough heating material available to heat them adequately. In addition, many of the children were not dressed as warmly as they should have been; there was often a lack of gloves or hats.

Individual fates

- In Beadle County , South Dakota , farmer Robert Chambers was surprised outdoors with his nine-year-old son and their dog, a Newfoundland dog. Unable to find their way back to their farm, they buried themselves in a snowdrift, with the father wrapping his son in pieces of his clothes. The next morning, a group of men searching for them became aware of the barking dog. The father was frozen to death by the time the boy survived.

- In Plainview , Nebraska , the young teacher Lois Royce initially stayed in the school house with three of her students. At 3 p.m., however, they ran out of fuel. Since Lois Royce's home was only 85 meters from the school, she tried to lead the children there. However, because the view was so limited, they lost their bearings on the way there. They tried to get through the night by lying four of them on the floor under the teacher's coat. The three children, two nine-year-old boys and one six-year-old girl, did not survive the night. The teacher had to have both feet amputated due to frostbite.

- In Holt County, Nebraska , young teacher Etta Shattuck lost her bearings on the way home, but found shelter in a haystack. She waited three days under the frozen and snow-covered hay before she was found. She died shortly afterwards of complications from her leg amputation, which became necessary due to frostbite.

Aftermath

The poet and Pulitzer Prize winner Ted Kooser , born in 1939, recalled numerous individual fates in his volume of poetry "The Blizzard Voices" . Since 1967, a wall mosaic in the Nebraska State Capitol building has also commemorated the dead from this weather event. The semi-abstract mosaic takes up the possibly inaccurate story of a teacher who led her students through the storm to safety by tying them up with a clothesline.

See also

literature

- David Laskin: The Children's Blizzard. HarperCollins Publishers, New York 2004, ISBN 0-06-052075-2

- Bill Streever: Cold. Adventures in the World's Frozen Places. Back Bay Books, New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-316-04292-5

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/03/obituaries/minnie-mae-freeman-penney-overlooked.html

- ↑ Laskin, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Laskin, pp. 51-60

- ↑ Laskin, p. 129

- ↑ Laskin, p. 129

- ↑ quoted from Steever, p. 23

- ↑ Laskin, p. 130

- ↑ Laskin, p. 135

- ↑ Laskin, pp. 135, 136

- ^ Laskin, p. 136

- ↑ Laskin, p. 200.

- ↑ Laskin, p. 199.