Weirdos from the cave monastery district

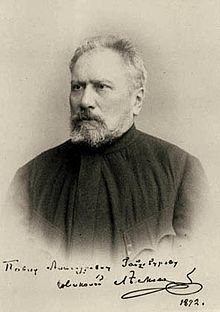

Oddities from the cave monastery district ( Russian Печерские антики , Pecherskije antiki ) is a story by the Russian writer Nikolai Leskow , which was published in 1883 in the magazine Kijewskaja starina (Kiev antiquities).

The time before the Crimean War - before 1853: Born in 1831 Leskov remembers - as an adult in the "current bank age" living - his youth in Kiev and chats about local whimsical owls.

frame

Bibikow, general of the infantry and in the years 1837-1852 governor general of Kiev , wanted to build a new Kiev at the time. Dilapidated dwellings in the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra district were affected by the demolition. Caesar Stepanowitsch Berlinski, Colonel of the Artillery, lives in the same quarter, did not play along. The colonel gathered residents around him; derelict officers and older students who resisted the demolition. Berlinski had good cards. As a deserving veteran, he had free access to the Tsar . In response to his intervention, the colonel received a promise from the ruler: His property in the cave monastery district must be spared demolition.

From the extensive gallery of Old Kiev originals presented in the text, some are sketched below that Leskow narrated out.

Anecdotes

The tsar solved all of the colonel's problems - irrespective of whether it was a question of raising the salary or training the band of children of the widowed Berlinski. When the Colonel was in Petersburg in 1836 , the wooden Lehmannsche Schaubude with spectators burned down on Admiralty Square. In retrospect, Berlinski acted as an advisor to the shocked ruler. In the opinion of the colonel, the artillery should have been used immediately instead of the fire brigade with their hoses. The tsar did not understand. Why then artillery? Well, replied Berlinski, a shot at the burning booth would have killed a large number of spectators, but the rest of the survivors could have quickly escaped from the two bullet holes. Leskow interjects that a cannonade under the command of the Colonel would not have gone well, because Berlinski was so popular with the cannoners that they all left their posts at the cannon and rallied directly around the commander.

Once the colonel treated the sick tooth in the upper jaw of Bibikov's mother-in-law. The son-in-law did not allow this voluptuous and huge lady into Kiev - allegedly because of her lack of character. Of course, Berlinski had a doctor up his sleeve for the emergency operation - his nephew Dr. Nikolai. This schoolmate of Leskov's was called Nikolavra. Nikolawra's medicine - a highly effective liquid that was dripped onto the painful area - was principally only applicable to one tooth in the lower jaw. The colonel knew how to deal with women militarily. He turned Bibikow's mother-in-law upside down. The woman, pain-free in no time, was able to start her almost missed pleasure trip to Paris. Quite a few women from the better Kiev society wanted to be cured from now on according to the Berlinskisch turning method. Dr. Nikolavra, a serious doctor, went on strike - then left Kiev.

The colonel not only tolerated officers and students in his neighborhood. For example, the excellent Latin Ivan Dionissovich - half Polish , half Little Russian - had the right to live in the cave monastery district . In his high-level language, which the Jesuits had taught him at a young age , he talked to another ancient intellectual aristocrat about subjects that can only be inadequately dealt with in the lower plebeian dialect. The Latin was an artist in three ways. Italic language proficiency was mentioned. In addition, he was able to cut his own hair and managed to artificially age brand-new boards at high speed in a lye made from cow dung and other various ingredients. The latter art was highly valued by Berlinski; it was used for daily necessary "antiquarian" house repairs in the district of the deception of his intimate enemy Bibikow.

The colonel allowed the billeting of Starez Malafej, an 80-year-old non-prayer . Old Believer Russians - more precisely, two masons - who built the chain bridge over the Dnieper in the wake of the Englishman Vignoles , had smuggled the sectarian Malafey into Kiev for the purpose of pastoral care. The elderly non-worshiper lived with his servant Gehazi, who was around 23 years old, hidden in a backyard that was difficult to access in a spacious but poor hut, because non-worshipers were considered political offenders at the time; as an adversary of the tsar. Leskow calls Malafej's dwelling a prayer stable because it used to be used to raise poultry. The Starez's opponents had rented themselves in the neighborhood - pomorans , which from a liturgical point of view were attached to the troparion . Berlinski had a brief description of each of his residents. For Malafej it was: "A fool in Christ."

Malafej was priest of the Raskolnics . That is why Gehasi still acted as a church servant and novice. The starez punished Gehasi's misconduct by letting a wet rope dance on the unfortunate's back. As soon as the pomorans next door started their singing, Gehazi called over: "Troparists - false Christians!" The insulted, not lazy, replied: "Non-worshipers - dung-kneaders!"

The day after the inauguration of the Chain Bridge by the Tsar, Gehazi visited Leskov. Malafej, who had followed the consecration of the bridge from a safe distance, wanted to know what the ruler had said to the two gentlemen who had stood in his way during the ceremony in the middle of the bridge. The gentlemen, two landowners from Zvenigorod , were distant relatives of Leskov. The respondent was thus able to determine the content of the conversation. The Starez was badly disappointed by the result of the investigation. It was not a dialogue about the interpretation of the faith, nor was there any talk of the rumored association of faiths. The ruler had only ordered the two farmers: "Get out!"

Years later, Leskow met Gehazi in Kursk . Gehazi was now married and had children. Although the former servant was now free, he suffered from stomach cancer at a late stage. Gehazi said he endured the tyranny of Malafej for 33 years; had to survive the fast, but then fell ill.

German-language editions

Used edition

- Weirdos from the cave monastery district. Excerpts from childhood memories. German by Wilhelm Plackmeyer . P. 601–697 in Eberhard Dieckmann (Ed.): Nikolai Leskow: Collected works in individual volumes. 4. The unbaptized priest. Stories. With a comment from the editor. 728 pages. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1984 (1st edition)

See also

- Kiev Pechersk Lavra ,

- Professor Vasily Klyuchevsky ,

- Nikonians .

Web links

- The text

- Entry in the Laboratory of Fantastics (Russian)

annotation

-

↑ Some of the more well-known personalities that Leskow mentions or about whom he tells, for example (the page numbers refer to the edition used)

- Viktor Ipatjewitsch Askochensky (1813–1879, Russian Аскоченский, Виктор Ипатьевич , p. 649),

- Alexei Onissimowitsch Janowitsch (1831–1871, Russian Янович, Алексей Онисимович , p. 649),

- Andrei Iwanowitsch Podolinski (1806–1886, Russian Подолинский, Андрей Иванович , p. 650),

- Editor of the first Kiev newspaper Alfred von Jung († around 1870, Russian Kiewer Telegraph , p. 651),

- Andrei Iwanowitsch Drukart (Russian Андрей Иванович Друкарт, p. 657), at the time employed by the Kiev civil governor,

- Bishop Filaret (secular name Filaretow) (1824–1882, Russian Филарет (Филаретов) , p. 678), at that time rector of the Kiev Spiritual Academy and

- Bishop Innokenti (secular name Borissow) (1800–1857, Russian Иннокентий (Борисов) , p. 690).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Russian Киевская старина

- ↑ Dieckmann in the notes of the edition used, p. 723, 9. Zvu

- ↑ Russian Dmitri Gawrilowitsch Bibikow

- ↑ russ. Кесарь Степанович Берлинский, see also Order of St. George , 4th Class on December 4, 1843 ( Берлинский, Кесарь Степанович; капитан; № 7105; 4 декабря 1843 )

- ↑ Russian Admiralty Square

- ↑ Russian балаган Лемана, see also fire in the Lehmannsche Schaubude (Russian)

- ↑ see also Gehasi

- ↑ Kljutschewski, mentioned on p. 642 in the middle of the edition used

- ↑ Nikonianer, mentioned from p. 643, 13. Zvo of the edition used