Temple of the Magna Mater

Coordinates: 41 ° 53 '22.2 " N , 12 ° 29' 5.8" E

The temple of the Magna Mater was one of the temples on the Palatine Hill in Rome . The Magna Mater cult was based on a saying in the Sibylline Books during the Second Punic War in 204 BC. Introduced in Rome. That year a Roman delegation brought a meteorite stone from the Phrygian sanctuary of the goddess Cybele in Pessinus to Rome. The stone was worked into a silver statue and first placed in the Temple of Victoria on the Palatine Hill. The Romans named the Phrygian goddess Mater Deum Magna Idaea (Great Mother of the Gods of Mount Ida). On April 11, 191 BC A separate temple was dedicated to her on the Palatine Hill. On this occasion, the Ludi Megalenses , which were celebrated in front of the temple from April 4th to 11th, were introduced as a cultic festival . The Fasti Antiates maiores and the Fasti Quirinales are considered to be the oldest textual witnesses to the dating of the festive season. Later Fasti traditions contain a transmission error, which is why the fixed period 4 to 10 April given there is to be regarded as incorrect.

Building history

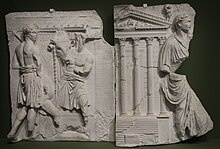

The first, 191 BC. Chr. By the praetor Marcus Junius Brutus consecrated building burned in the year 111 BC. BC, but was immediately taken by a Metellus, probably the consul of 109 BC. BC, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus , rebuilt only to fall victim to another fire in 3 AD. Augustus renewed this building - aedem Matris Magnae in Palatio feci ("I built the temple of the Magna Mater on the Palatine Hill"; res gestae 19) - which finally survived into the fourth century. On the west side of the palatine, at the upper end of the Scalae Caci , among the remains of a temple were numerous inscriptions to be connected to the Magna Mater, part of a larger-than-life seated statue and fragments of a base with paws of lions, the usual accompanying figures of the goddess. The identification of the temple with that of the Magna Mater is therefore considered certain.

Description of findings

The podium of the temple in particular is well preserved, and fragments of the column bases, the capitals and the geison can also be assigned to the building. In general, the fragments are associated with the Augustan renewal, but they could also be linked to an unsanitary repair from around 40/30 BC. To be connected.

According to the podium, the temple was about 17 meters wide and 33 meters long. The podium made of Opus caementitium clearly shows two phases of construction, which are to be connected with the Metellic building and the Augustan building. Accordingly, the podium was significantly increased in Augustan times. For this, the entire older building fabric of the rising architecture of the Republican era must have been removed. It is possible that the fragment of an Italic-Corinthian capital found during the excavations can be assigned to the external order of the Metellic construction phase. An Italic-Ionic capital found in the cella could be linked to the interior arrangement of this building.

According to the archaeological findings, the Augustan temple was a hexastyle prostylos with four columns deep porch. The columns stood on plinthless Attic bases and carried Corinthian capitals , each made of two pieces. The base length was 1.34 meters, the lower column diameter 1.02 meters, so that a column height of about 10 meters can be determined. The unusual absence of the plinth on the column bases of the Middle Augustan period suggests that the bases are reused structural members from a previous Republican building. The entablature has not been preserved, but can be reconstructed with Ionic architraves and friezes in analogy to all other buildings in Rome from this period . This was followed by the partially preserved console geison . All external structural members were made of peperine and covered with white stucco. This is noteworthy insofar as all other Augustan temple structures that Augustus himself boasted of having renovated were made of marble .

The temple had an interior arrangement with Corinthian columns, which rose along the long sides on a pedestal, the cementicium core of which is still preserved. The associated capitals were made of marble, and the paviment was also made of marble slabs. The entire width of the back of the cella took up a narrow space that was not exactly definable in terms of its function. Whether it was accessible cannot be decided based on the findings. In front of the center of the rear wall of the cellar are the remains of cement from a large base that carried the cult image. Nothing is known about the further equipment of the cella.

literature

- Pierre Gros : Aurea Templa. Research on l'architecture religieuse de Rome à l'époque d'Auguste . 1976, pp. 232-234.

- Patrizio Pensabene in: Roma. Archeologia nel centro I. De Luca, Rome 1985, p. 182 ff.

- Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 9, 1988, p. 54 ff.

- Patrizio Pensabene: Magna Mater, Aedes. In: Eva Margareta Steinby (Ed.): Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae . Volume 3. Quasar, Rome 1996, pp. 206-208.

- Ralf Schenk: The Corinthian Temple until the end of the Principate of Augustus. M. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1997, pp. 158-159, ISBN 978-3-89646-317-3 .

- Torsten Mattern : The Magna Mater Temple and the Augustan architecture in Rome. In: Roman communications . Volume 107, 2000, pp. 141-153 ( online ).

Remarks

- ↑ Ovid , Fasti 4, 258.

- ^ On cult and Rome: Franz Bömer in: Römische Mitteilungen. Volume 71, 1964, pp. 130 ff .; Karl Schillinger: Investigations into the development of the Magna Mater cult in the west . 1978, p. 333 ff .; TP Wiseman: Cybele, Virgil, and Augustus. In: Tony Woodman, Anthony John Woodman, David Alexander West (Eds.): Poetry and Politics in the Age of Augustus. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1984, pp. 117 ff.

- ↑ Herodianus 1:11 ; Arnobius the Elder , adversus nationes 5, 5.

- ↑ Livy XXIX, 14, 13; Harald Haarmann: The Madonna and her Greek daughters, reconstruction of a cultural-historical genealogy. Olms, Hildesheim et al. 1996, ISBN 3-487-10163-7 , p. 129.

- ↑ Barbara Kowalewski: Female figures in the history of T. Livius. KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-598-77719-1 , p. 197.

- ^ Jörg Rüpke : Errors and misinterpretations in the dating of the "dies natalis" of the Mater Magna temple in Rome. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . Volume 102, 1994, pp. 237-240.

- ↑ Valerius Maximus 1, 8, 11; Tacitus , annales 4, 64; Ovid, fasti 4, 374f .; Augustus, res gestae 19; compare also Cassius Dio 55, 12, 4 and Suetonius , divus Augustus 57, 2.

- ↑ Notitia regionum urbis Romae X

- ↑ CIL 6, 496 , CIL 6, 1040 , CIL 6, 3702 .

- ↑ to excavations and temples: Fritz Toebelmann: Römische Gebälke. Volume 1. Heidelberg 1923, pp. 5-6 Fig. 5; Peter Hommel: Studies on Roman figure gables of the imperial era. Mann, Berlin 1954, p. 30 ff .; Patrizio Pensabene in: Roma. Archeologia nel centro I. De Luca, Rome 1985, p. 182 ff .; Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 9, 1988, p. 54 ff .; Ralf Schenk: The Corinthian Temple until the end of the Principate of Augustus. M. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1997, pp. 156-159.

- ↑ Paul Zanker : Augustus and the power of images . 1987, p. 115; Pierre Gros: Aurea Templa. Research on l'architecture religieuse de Rome à l'époque d'Auguste. École française de Rome, Rome 1976, p. 234.

- ↑ Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 5, 1983, p. 72; Ralf Schenk: The Corinthian Temple until the end of the Principate of Augustus. M. Leidorf, Espelkamp 1997, p. 158f.

- ↑ on the Metellic Caementicium: Pietro Romanelli in: Monument Antichi. Volume 46, 1963, pp. 232-235 .; Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 9, 1988, p. 59.

- ^ Pietro Romanelli in: Monument Antichi. Volume 46, 1963, pp. 235-237; Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 9, 1988, p. 60.

- ↑ On the construction phase of Metellus: Patrizio Pensabene u. a. in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 11, 1993, p. 28 ff .; Patrizio Pensabene in: Bulletino Archeologico. Vol. 11-12, 1991 (1994) pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 5, 1983, p. 72.

- ↑ Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 1, 1978, pp. 69-70; Patrizio Pensabene in: Archeologia Laziale. Volume 3, 1980, p. 67; Patrizio Pensabene in: Roma. Archeologia nel centro I. De Luca, Rome 1985, p. 182.