Tibetan monarchy

The Tibetan monarchy , even Yarlung dynasty called or in contemporary Chinese-language sources Tǔbō or Tǔfān吐蕃was a section of Tibetan history. It originated in the 7th century in a side valley of the Tsangpo (upper reaches of the Brahmaputra ), the valley of the Yarlung River , and sank in 842.

meaning

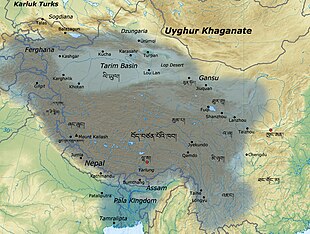

The Tibetan monarchy was the first larger politically and historically tangible Tibetan empire that, in addition to the Tibetan highlands, ruled large parts of Central Asia and, at times, Chinese areas. With the creation of a central imperial administration, Tibet opened up to the cultural and spiritual influences of the high cultures of India and China. In this respect, the spiritual basis for the Tibetan culture of the 2nd millennium AD was laid at that time.

This vast expanse remained unique in Tibetan history. None of the later Tibetan empires ever regained power over the entire Tibetan-populated area, not even that of the Dalai Lamas .

Historical availability

The traditional Tibetan royal list of the rulers of the dynasty lists 42 kings, of which the first 26 are to be regarded as mythical ancestors; only from the 27th ruler onwards are they considered historical personalities by modern research. From the 33rd king onwards, the rulers are well known from a variety of Tibetan and non-Tibetan sources.

It was only under Kings 31 to 33 that a uniformly governed Tibetan state emerged, which extended its control far over the region of the southern Tibetan Yarlung Valley. In the 7th and 8th centuries, the rulers Songtsen Gampo and Trisong Detsen were able to incorporate not only other Tibetan kingdoms such as Shangshung into their empire through a clever marriage policy, but also through intrigues and campaigns , but also conquered other areas beyond the Tibetan highlands on the Silk Road and in 763 even the capital of the Chinese Tang dynasty for a short time (cf. Tang dynasty ).

Designations of rulers

Due to later Buddhist overprinting, the rulers, who were called Tsenpo ( btsan po ), are mostly called kings ( rgyal po ). In fact, however, Tsenpo is a title of ruler that was reinterpreted as "Dharma King" ( chos rgyal ) , especially during the time of the 5th Dalai Lama .

The early days

As the mythical ancestor of the Yarlung dynasty, named after its center of power in the valley of the Yarlung River , a tributary of the Yarlung-Tsangpo in southern Tibet, Ode Pugyel was initially considered (legend after Wylie : 'o lde spu rgyal ). Nyathri Tsenpo ( gnya 'khri btsan-po ) appears in the list of rulers as the first of the seven mythical "heavenly kings" with whom the dynasty, according to legend, began; they are said to have descended from heaven and returned there when they died without leaving a corpse. Only the eighth king broke off the connection to heaven; ever since the kings were mortal people like their subjects. Only the 27th king, Thrije Thogtsen ( khri rje thog btsan ) is attested as a quasi historical personality . His successor Thothori Nyentsen , who lived in the 5th century, is said to have founded the residence Ombu ( om bu ), better known as Yumbulagang . At that time there was no unified Tibetan state; the power of kings was probably limited to the Yarlung Valley.

Expansion under Namri Songtsen

In Chingpa ( 'phyings pa ) in the Yarlung valley, the prince Thri Longtsen ( khri slong brtsan ) ruled . He defeated Singpoje ( zing po rje ) from Ngepo ( ngas po ) in the upper Kyi-Chu valley , occupied its land and named it Phenyül ( 'phan-yul ). The Tibetan Empire was founded and Thri Longtsen proclaimed ruler ( btsan po ). He was given the name Namri Songtsen ( gnam ri srong btsan ). In the traditional list of rulers he appears as No. 32. The three most influential princes of We ( dbas ), Nyang ( myang ) and Nön ( mnon ) recognized his suzerainty and became supreme advisers. Donations of land and privileges turned former tribal princes into feudal lords. Pungse Sutse ( spung sad zu tse ), a favorite of the king, killed the prince of Tsangbö ( gtsang bod ; later Tsang ) and received his territory as a fief. The Dagpo region ( dwags po ) resisted and was conquered. The position of the Grand Minister ( blon po chen po ; Lön Chenpo; short: blon chen ) was created. Around 620 the king died of poison as a victim of a conspiracy.

Songtsen Gampo

His successor, the underage Thride Songtsen ( khri lde srong btsan ; † 649), known to posterity as Songtsen Gampo ( srong btsan sgam po ), held a bloody judgment at the poisoners and vigorously restored order.

The old minister Nyangmang Poje ( nyang mang po rje ) was slandered and executed by Pungse Sutse ( spung sad zu tse ), as was his successor Garmang Shamsum Nang ( mgar mang zham sum snang ). Then Pungse Sutse became a minister himself. He sought the king's life, who was saved by Gar Tongtsen Yülsung ( mgar stong brtsan yul zung ). Eventually Pungse Sutse committed suicide and Gar Tongtsen Yülsung became a minister. Under him, Tibet enjoyed inner peace for decades and is expanding into a major power in Central Asia.

The policy of the Tibetan royal court included the marriage of the Tibetan king to politically important neighbors. The Chinese emperor bought peace with Tibet by giving the king a princess ( Wen Cheng ) as his wife. She came to Tibet in 641. A few years earlier, Songtsen Gampo had married a Nepalese princess ( Bhrikuti ) and a daughter of the West Tibetan king of Shangshung . Although the king's court was nomadic, the city of Lhasa was established for the government and the king's wives .

The minister Thonmi Sambhota was sent to North India. There he developed the Tibetan alphabet based on the late Gupta script. At the same time, the spelling was essentially determined. The king also passed 18 laws. It was under him that Buddhism became known in Tibet .

The weak successors of the Songtsen Gampo

When Gungsong Gungtsen ( gung srong gung brtsan ), Songtsen Gampo's son entitled to inheritance, was 13 years old, Songtsen abdicated Gampo in his favor, but took the throne again after the young king's untimely death after five years of a sham government .

Mangsong Mangtsen ( mang srong mang btsan ; 649–676), was still a child when Songtsen Gampo died, and so the government remained in the hands of Minister Gar Tongtsen Yülsung until his death in 667. He was followed as minister by his eldest Son of Gar Tsennya Dembu ( mgar btsan snya ldem bu ), who continued the policy of expansion.

Thri Düsong Mangpo Je ( khri 'dus srong mang po rje ; 676–704) ascended the throne at the age of eight. When Minister Gar Tsennya died in 685, Tibet was a major Asian power. However, his successor and brother Gar Thridring ( mgar khri 'bring ) was less successful. The aristocratic opposition found support from the king. Gar Thridring was deposed and committed suicide in 698. This broke the power of the Gar family forever. The king took back the government and led the troops against China himself (albeit unsuccessfully).

Thride Tsugten ( khri lde gtsug brtan ; 704–755) was only a few months old when his father died, but his energetic grandmother Thir Malö ( khri ma lod ), supported by her family 'Bro, knew how to secure his successor. This only succeeded after a civil war in which the anti-king Cenlha ( gcen lha ) in Belpo ( bal po ; located in central Tibet, not to be confused with Nepal, which is also to be confused) was overcome. The coronation took place in 712. In this situation, the Minister We Thrisig Shangnyen ( dbas khri gzigs zhang nyen ; since 705) sought peace with China. In 710 a Chinese princess was married to the six-year-old king. Despite a brief conflict (714) with China, the peace lasted until the death of the minister 720. The later battles were overall successful.

Thrisong Detsen

Thrisong Detsen ( khri srong lde btsan ) ruled from 755 to 797 at the height of Tibetan power. Under General Tadra Lugong ( stag sgra klu gong ) the then Chinese capital Chang'an was conquered in 763 and held for three weeks. The great Tibetan acquisitions were confirmed in a peace treaty in 783, which only lasted two years. In 787 the Tibetan army was again close to the Chinese capital, but a decisive defeat in 789 forced a retreat.

The king pursued a pro-Buddhist policy. To support the construction of a large temple, he first invited the Indian master Shantarakshita from the temple at Nalanda to Tibet, but according to tradition, his means were not sufficient to tame “the evil gods and demons of Tibet”. Therefore the important tantric Padmasambhava was called to Tibet, where he started the construction of the Samye ( bsam yas ) monastery around 775 . An edict promulgated in 779 made Buddhism the state religion, and the Council of Samye 792-794, chaired by the king, decided the dispute between the Indian and Chinese parties in favor of the Indians. In cooperation with Indian scholars, the translation of the Mahayana literature into Tibetan began.

It is not certain whether the king died in 797 or abdicated and became a monk.

The weak successors of the Thrisong Detsen

Mune Tsenpo ( mu ne btsan po ; 797–799), the eldest living son of the Thrisong Detsen, ruled for only two years.

His successor was his third brother Brave Tsenpo ( mu tig btsan po ), also called Thride Songtsen ( khri lde srong btsan ; 799-815) or Sena Leg ( sad na legs ). The real ruler, however, was probably the second brother Murug Tsenpo ( mu rug btsan po ) until his death in 804. Under this weak king there were various defeats during incursions into China. In 802 even the Grand Minister ( blon chen ) We Mangje Lhalö ( dbas mang rje lha lod ) was captured.

The influence of the Buddhist clergy can be seen in two influential monks: Nyang Tingnge Dzin ( myang ting nge 'dzin ), who traveled to China as an envoy in 804, and Dranka Yönten Pel ( brang ka yon tan dpal ), who was given the new title around 810 "Grand Minister of Administration" ( chab srid kyi blon po chen po ) actually headed the government.

Relpacen

Thritsug Detsen ( thri gtsug lde brtsan ; 815–838), usually called Relpacen ( ral pa can ), was the son of his predecessor, Brave Tsenpo and a staunch Buddhist. The translation activity of Buddhist scriptures flourished and was organized by the state.

Politically, Tibet, like China, was in a slow decline. In 822, both countries signed a peace treaty negotiated by Dranka Yönten Pel, which confirmed the Tibetan possessions. This peace treaty was drafted in two languages and can be read on a stele in Lhasa.

The nobility, weakened by the close coalition of king and clergy (and connected to the Bon religion), was able to achieve the execution of Dranka Yönten Pel through intrigues. Nyang Tingnge Dzin was also killed. Shortly thereafter, the king fell victim to a nobility conspiracy and was murdered by We Tagna ( dbas stag sna ) and Cogro Legdra ( cog ro legs sgra ).

Lang Darma

The conspirators installed Thri Udum Tsen ( khri u dum btsan ; 838-842) as king, who was usually called Lang Darma ( glang dar ma ) and was a brother of the murdered man. Under the new Grand Minister ( blon-chen ) Wegyel Tore Tagnya ( das rgyal to re stag snya ) a policy of extermination against Buddhism began. The foreign monks were expelled, the Tibetan monks laicized. There were also earthquakes and the plague. Finally, Lang Darma was murdered with an arrow shot by the monk Pelgyi Dorje ( dpal gyi rdo rje ) - who then escaped his pursuers.

The end of the monarchy

The king died childless. The Chim ( mchims ) family tried to come to power by pretending to be a son of the widow's elder brother (a Chim princess) as the later son of Lang Darma. He was given the royal name Thride ( khri lde ), but became known to posterity as Yumten ( yum brtan or yum rten ) in view of the support from his mother . Shortly afterwards, a co-wife of Lang Darma gave birth to a son who was proclaimed King Namde ( gnam lde ), usually called Ösung ( 'od srungs ), by the - probably Buddhist - opposing party . The result was an indecisive civil war. The outside holdings were lost. In the following generations there was a severe fragmentation of political power.

De Pelkhor Tsen ( lde dpal 'khor btsan ), the son of Ösung, was killed by his subjects. The descendants of his younger son Thri Trashi Tsegpa Pel ( khri bkra shis brtsegs pa dpal ) could only survive in Yarlung by becoming hereditary abbots of the Cilbu monastery ( spyil bu ). The older son Kyide Nyima Gön ( skyid lde nyi ma mgon ) emigrated to the west. His successors founded empires there like Ladakh or Guge , which saved the Tibetan kingdom until the 19th century.

See also

literature

- Erik Haarh: The Yar-luñ Dynasty , Kobenhavn 1969.

- Erik Haarh: Extract from The Yar Lun Dynasty . In: The History of Tibet . ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003.

- Christopher Beckwith: The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia. A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, Chinese during the Early Middle Ages . Princeton University Press, Princeton New Jersey 1987, ISBN 978-0691024691

- Hugh Richardson: The Origin of the Tibetan Kingdom . In: The History of Tibet . ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003.

Web links

- The Tibetan Empire (PDF; 56 kB)

- Tubo Kingdom (Tǔbō 吐蕃 )

- Yalung Valley Dynasty 雅隆 谷 王朝

- Qingwa Dagze Palace ruins and Gyima Palace ruins

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tǔbō corresponds to the etymology chin. Bō蕃 <tib. Bod བོད་ (or Tǔbō吐蕃 < sto bod སྟོ་ བོད་, mtho bod མཐོ་ བོད་ or dur bon དུར་ བོན་), cf. Sanskrit bhoḍa བྷོ་ ཌ་, Mongolian töbed ᠲᠥᠪᠡᠳetc. (see Xiàyù Píngcuòcìrén 夏 玉 ・ 平措 次仁: Zàngshǐ míngjìng《藏 史 明镜》 / deb ther kun gsal me long ༄ ༅ ༎ དེབ་ཐེར་ ཀུན་ གསལ་ མེ་ལོང་ །. Lhasa: Xīzàng rénmín chūbǎnshè西藏 人民出版社 / bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang བོད་ ལྗོངས་ མི་ དམངས་ དཔེ་ སྐྲུན་ ཁང་ །, 2011; ²2016; p. 5 f.) This pronunciation is also used in Hé Jiǔyíng 何九盈, Wáng Níng 王宁, Dǒng Kūn 董 琨 (Ed.): Cíyuán《辭 源》. Beijing: Shāngwù yìnshūguǎn 商务印书馆, ³2015 and in Liú Gǎo 刘 杲 et al. (Ed.): Xiàndài Hànyǔ dà cídiǎn《现代 汉语大词典》. Shanghai: Shànghǎi císhū chūbǎnshè 上海 辞书 出版社, 2010 cited.

- ↑ Tǔfān according to 《教育部 重 編 國語 辭典 修訂 本》 from Taiwan and according to 《现代 汉语 词典》 from mainland China.

- ↑ Haarh, Erik: Extract from "The Yar Lun Dynasty" , in: The History of Tibet , ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003, p. 147; Richardson, Hugh: The Origin of the Tibetan Kingdom , in: The History of Tibet , ed. Alex McKay, Vol. 1, London 2003, p. 159 (King List pp. 166-167).

- ↑ See e.g. B. Beckwith 1987, p. 14; Gruschke, The Qinghai Part of Amdo , Bangkok 2001, p. 211f./note 17 as well as page no longer available , search in web archives: Glossary by Brandon Dotson, “Emperor” Mu rug btsan and the 'Phang thang ma Catalog , in JIATS

- ↑ "From Yarlung to Lhasa", Chapter 4 in: Gruschke, Andreas: 'Myths and legends of the Tibetans. From wars, monks, demons and the origin of the world ", Munich 1996, pp. 139–180.

- ↑ Haarh, Extract , pp. 146-152.