Tifinagh script

Tifinagh or Tifinare (own name ⵜⵉⴼⵉⵏⴰⵖ tifinaɣ , traditionally written as ⵜⴼⵏⵗ or ⵜⴼⵉⵏⵗ ) is the name of the traditional script of the Tuareg . It is of Berber origin and developed from the Libyan script , which in turn was most likely based on the model of the Phoenician alphabet .

Tifinagh or more correctly Neo-Tifinagh is also a script introduced around 1980, which was developed on the basis of the Tuareg script to write modern Berber languages. It competes with the previously customary spelling of Berber languages with Latin or Arabic letters.

origin of the name

Whether the name Tifinagh originally meant "the Phoenician [letters]" is a matter of dispute. The "ti-" in the font is a prefix that characterizes feminine nouns in the plural, "finagh" is the actual root. In Berber languages the designation for languages is usually the feminine singular, which is characterized by a "t" at both the beginning and the end, such as "Ta-schelhi-t" for the language of the Shilah or "Ta-rifi-t" for the language of the Rif-Berbers. A hypothetical singular would then be "Ta-finigh-t".

Short inscriptions can already be found on the pre-Christian rock carvings of the Sahara, although it is not clear whether the characters were added later. The Tuareg cite a mythical hero named Aniguran or Amamella as the "inventor" of their script .

General

The traditional alphabet of the Tuareg consists of 21 to 27 geometric characters depending on the region. There are no vowels or hyphenation, and word direction is not fixed. This means that you can write from top to bottom, from right to left or vice versa. This makes the writing very difficult to read.

Contrary to popular belief, the Tifinagh was never used to write longer texts. The texts known from the pre-colonial period mostly consist only of short inscriptions on rocks (names or messages) and names and formulaic blessings on leather amulets or pieces of jewelry. The blades of the famous Tuareg swords in particular were often decorated with Tifinagh symbols, which were supposed to bring good luck to the warrior. In Morocco, Tifinagh characters are traditionally painted on the skin with henna or other dyes for magical purposes. In the case of newborns, they are supposed to render evil spirits and envious people or their " evil eye " harmless.

There was no literature that was written in Tifinagh. The educated classes among the Tuareg, the Inislims 'men of Islam', have been using the Arabic script since the Middle Ages. The chronicles of the individual Tuareg and Berber confederations, such as the Chronicle of Agadez , were not written in Tifinagh, even if they were written in a Berber language and the Berber phonemes did not always correspond to the Arabic symbol. Tuareg princes, who themselves did not speak Arabic, always had a man who knew how to write, usually a marabout , who handled correspondence with other Tuareg groups or with Arab, Moorish or - for example in the late 19th century - Ottoman addressees (in Murzuk or Tripoli ) - led.

One of the most famous myths surrounding the Tuareg culture is that the mothers taught their children the traditional script. In fact, it is at best a generalization of exceptional cases. Most of the Tuareg were illiterate, the written means of communication was at best Arabic. Only in the aristocratic clans, where women were not drawn to the physically difficult work, was such traditional knowledge imparted.

The two Africa explorers Heinrich Barth and Henri Duveyrier , who lived among the Tuareg for a long time between 1850 and 1860 and were able to research everyday life in detail, know nothing of such Tifinagh lessons. Both would certainly have reported about it, since they faced the desert nomads with an open mind and tried to paint as positive a picture of this people as possible. The myth of mothers teaching Tifinagh to their children arose in the 20th century in light of the widespread belief that Tuareg society was matriarchal , and in the light of such an interpretation it made sense for mothers, i.e. H. the women, as almost high priestly guardians of "ancient" traditions were portrayed.

Recent developments

At least the children of the noble clans learned the script from their mothers, but this custom has long since dwindled, since the Tifinagh is no longer needed in view of both Arabic and French. Longer texts are not written in this font anyway. In the early 1970s, a Targi from Timbuktu developed a modified cursive script that was intended to remedy some of the Tifinagh's major shortcomings: the writing direction was right to left, words were clearly separated from one another, and the vowels were now designated. Despite this modernization, the Tifinagh-n-azzaman , the 'renewed Tifinagh', has only been able to establish itself with a circle of traditional Tuaregs .

In view of the drought that began at the same time, the already rapid decay of the traditional Tuareg culture was only accelerated, and the governments, which were keen to make the nomads settle down if necessary, saw no reason to promote the spread of a script, which was suitable to increase the self-confidence of the Tuareg and to support their demand for independence.

Only in Niger did the government show consideration for the nomads and until the 1990s printed official announcements in Tifinagh, too, with the costs for this mostly being borne by foreign sponsors or aid organizations. It must be doubted whether these publications could even be read by the majority of the Tuareg.

During the colonial era, the French made certain efforts to prevent the Tuareg script from becoming extinct. Officers and colonial officials, who were enthusiastic about the culture of the Saharan nomads, collected sagas, fairy tales and songs and had them recorded by Tuaregs who knew how to write in Tifinagh, but the majority of the nomads would not have been able to read a coherent text in their traditional script . Their literature was passed on orally. There have even been cases of Christian missionaries composing scriptures in Tifinagh, but their efforts were not well received by the Muslim Tuareg. Translations of works of European literature - such as the Little Prince of Saint-Exupéry - remained rather a rarity, if not to say a curiosity.

The German ethnologist Herbert Kaufmann reported in the 1950s that especially in Mali , in the hinterland of Timbuktu , Tuareg children were grouped together in boarding schools and taught there by black auxiliary teachers ( moniteurs ). Not only were they told that as nomads they were the most primitive of all human beings, but they were also strictly forbidden to use their mother tongue and traditional script. After the withdrawal of the French, this type of education policy intensified even further and was one of the causes of the violent conflict between the black African ruling class in the country and the Tuareg.

Neo-Tifinagh

At the end of the 1960s, mainly Algerian intellectuals of Berber origin joined forces in Paris to form an Académie Berbère , whose main concern was the preservation of Berber cultural traditions in view of the Arab dominance and the associated Arabization of their home country.

The members of this movement were mainly members of the Kabyle people from northern Algeria. Tuareg did not belong to the Académie Berbère . One of the means by which they wanted to revive the self-confidence of the “Mazighen”, as they called themselves, was the adoption of the old Berber script for their literary works.

To improve readability, they developed a modernized version of the Tifinagh, which they called tifinagh tiynayin , internationally known as "Neo-Tifinagh". Neo-Tifinagh also separates words with a space, uses European punctuation marks, and is written from left to right like Latin scripts. Some characters were also invented to denote the vowels and express consonants that did not appear in Berber, but were needed for non-Berber names and terms - for example from Arabic or European languages.

Nico van den Boogert writes: “The result is a typeface that looks similar to traditional Tifinagh, but in reality is completely incomprehensible for Tuareg literate people.” Neo-Tifinagh is more an expression of a cultural identity than a means of written communication. There are hardly any publishers who are technically capable of publishing books in Neo-Tifinagh. The works of the Tuareg poet Hawad , who lives in France, have achieved a certain fame, who further developed the Neo-Tifinagh into a kind of calligraphy and is also popular with French-speaking readers.

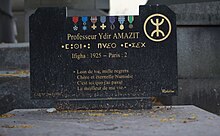

In Morocco , a similar development can be seen among the Schlöh -Berians (also called Schluh or Schilha ), who increasingly use the Tifinagh symbol for their language, the Taschelhit , in order to underline their cultural identity as Amazighen . In addition, within a few decades there has been a major change in acceptance: while the use of writing was still a criminal offense in the 1980s and 1990s, Tifinagh is now even taught in schools and can be found again and again on the streets of Moroccan cities.

Representation in Unicode

Tifinagh is coded from version 4.1 of Unicode in the range U + 2D30 – U + 2D7F (see Unicode block Tifinagh ). 55 characters have been defined, so not all characters used are mapped in Unicode. In the ISO 15924 standard , the Neo-Tifinagh was assigned the language code Tfng . The Tuareg language is called Tamaschek .

| code | +0 | +1 | +2 | +3 | +4 | +5 | +6 | +7 | +8 | +9 | + A | + B | + C | + D | + E | + F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U + 2D30 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| U + 2D40 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| U + 2D50 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| U + 2D60 |

|

|

||||||||||||||

| U + 2D70 |

Transcription of Tifinagh Figurines:

| colour | meaning |

|---|---|

| Simple Tifinagh (IRCAM) | |

| Extended Tifinagh (IRCAM) | |

| Other Tifinagh characters | |

| Modern Tuareg characters |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Examples

| German | Masirian | |

|---|---|---|

| in Tifinagh | in Latin | |

|

|

|

literature

- Nico van den Boogert: Article Tifinagh. In: Encyclopédie de l'Islam. Leiden 2002, Vol. 10, pp. 511-513.

Web links

- http://www.decodeunicode.org/w3.php?nodeId=70115&page=1&lang=1&zoom=&prop= (all characters)

- http://www.ancientscripts.com/berber.html

- http://www.mondeberbere.com/langue/tifinagh/tifinagh_origine.htm

- overview

Individual evidence

- ↑ Since it was the Greeks who gave the Levantine merchant people the name "Phoenicians", but the latter did not even have a name for themselves, it hardly seems credible that the Berbers adopted this term in their language and named their script after it.

- ↑ This problem was also known to the Turkish scribes of the Ottoman era, i. H. before the introduction of the modified Latin script, because the sounds of Turkish could not always be reproduced using Arabic characters.

- ↑ Nico van den Boogert writes on this: "In some clans, it is said that a good half of the women and a third of the men are able to write in Tifinagh without hesitation." See Encyclopédie de l'Islam , vol , P. 513. In any case, these vague figures do not speak in favor of widespread use of the font.

- ↑ Herbert Kaufmann: Riding through Iforas . Munich 1958, u. Ders .: Economic and social structure of the Iforas-Tuareg. Cologne 1964 (phil. Diss.)

- ↑ Encyclopédie de l'Islam. Vol. 10, p. 513.

- ^ Website of the Amazighen Movement