Visit format

With Visit format also de Carte Visite (abbreviation CdV) refers to a fixed on cardboard photograph cm in size from about 6 × 9th From around 1860 the Carte de Visite became very popular and contributed significantly to the spread of photography. After 1915 it can only be found very rarely. In the historical literature one can also find terms such as visiting card and visiting card , whereby the French word Visite was used in conjunction with a German word.

idea

When asked who first came up with the idea of the Carte de Visite , which differed from the other photographs in use at the time because of its small format, different answers are known. It wasn't long ago that the French photographer André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri was thought to be the inventor of the Carte de Visite . The photographer Gisèle Freund published in 1978:

“… Disdéri grasped all the shortcomings and realized that you could only achieve something in the photographic industry if you succeeded in increasing the circle of clients and increasing the number of portraits. But this could only be done if one adjusted to the economic conditions of the masses. And so Disdéri came up with a brilliant idea. He made the format smaller. He invented the Carte de Visite , the size of which corresponds roughly to our current 6 × 9 cm format. "

But earlier references to the format have been found. The first known mention of a portrait on a business card is in the August 24th issue of the French magazine La Lumiere . There, the art critic Francis Wey , who was a member of the Société héliographique , reported on the daguerreotypist and photographer Louis Dodero:

«Il nous raconte avec bonhomie que s'étant avise de mettre, au lieu de son nom, son portrait sur ses cartes de visite, ce caprice a été goute, a trouve des imitateurs, et, par la, popularize la découverte dans le pays . "

“In a good mood, he told us that it had occurred to him to put his portrait on his business card instead of his name; this whimsical idea was well received and imitated and this made his invention popular in the country. "

Dodero was ahead of his time when he was quoted in the text below: "If it were possible one day to make this process simpler and cheaper, it could also be used for passports, hunting permits, etc." He was of the opinion a photograph would be better suited to someone z. B. can be identified at the bank counter as a signature and a "banal" description of the appearance. In addition to his signature, he also included his portrait in his letters. In fact, nobody seems to have been enthusiastic about this idea, because it did not find any imitators and was therefore forgotten.

The next reference can be found in the October 28, 1854 edition of La Lumiere. There the editor Ernest Lacan wrote:

"Une idée originale a fourni à ME Delessert: et a M. le comte Aguado l'occasion de faire de délicieux petits portraits. Jusqu'à présent, les cartes de visite ont porte le nom, l'address, et quelquefois les titres des personnes qu'elles représentent. Pourquoi ne remplacerait-on pas le nom par le portrait? »

“Messrs E. Delessert and Count Aguado had an original idea in which they made lovely little portraits. Until now, business cards have had the name, address and sometimes the title of the person who introduced themselves. Why shouldn't one replace the name with the portrait? "

Delessert and Aguado's ideas were less of a benefit than of social interaction. They imagined that everyone should carry a number of different portraits. When you come to visit, the portrait (on the business card) should show "in impeccable gloves, the head slightly inclined as if in greeting, the hat placed on the right thigh according to the label". As they parted, they imagined a portrait "that shows you in travel clothes, the peaked cap on your head, your body wrapped in a blanket, your legs in wide fur boots, your travel bag in your hand."

Barely four weeks after this publication, the enterprising André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri applied for a patent on the Carte de Visite on November 27, 1854 . Amazingly, he didn't start working with this format until 3 years later. And it took a total of five years until he succeeded in 1859 from Emperor Napoleon III. to take a photograph in the Carte de Visite format , as a result of which this format became very popular.

Another quote about the Carte de Visite can be found in Haydn's Dictionary of Dates . We are talking about the first small photograph by "M [onsieur] Ferrier". was made in Nice in 1857. The Duke of Parma stuck his portrait on his business card.

Manufacturing

The challenges that Disdéri recognized were the technical implementation of the small format, increasing productivity and reducing costs.

Carte de Visite -Fotografien were on board reared paper copies of collodion wet plates - negatives and since 1864 to uranium-collodion coated paper. This wothlytypie process made it possible to obtain direct prints and to draw them on paper.

The collodion wet plates or wothlytype papers were exposed with special cameras. Small negatives were not enlarged , the problem was rather to achieve a correspondingly small recording format; around 1850 the plate sizes were between 6½ × 8½ inches = 16.5 × 21.6 cm = full plate and 2 × 2½ inches = 5.1 × 6.4 cm = ninth plate.

André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéris special camera therefore had four lenses and a sliding plate cassette . With the help of the multiple optics, four exposures could be recorded on each half of the glass plate; then the plate was moved with the aid of the cassette and the next four exposures could be recorded on the second half.

format

Subsequently, prints in negative format of approximately 8 × 10 inches = 20.3 × 24.5 cm were made on albumin paper , which were cut into 8 carte de visite formats (6 × 9 cm). The cutting process could take place directly in the Wothlytypia. The photograph was usually 54 mm (54 to 60 mm) wide and 92 mm (85 to 97 mm) high, and was printed on cardboard measuring approximately 65 mm (60 to 67 mm) wide and a Mounted height of 105 mm (101 to 107 mm).

carton

The cardboard boxes on which the prints were glued were u. a. offered by specialized manufacturers. The sale was through the trade in photographic articles. At the beginning of its popularity, the cardboard was inferior, about 0.4 mm thick and cut by hand. The thickness of the cardboard increased over time, about 0.1 mm per decade. As a rule, this applied to CdV formats; larger formats, which came up later, and thus also more expensive formats, were approx. 1 mm thick from the start. This thickness made it possible to produce beveled and colored cut edges. The backs have become more and more complex over time.

popularity

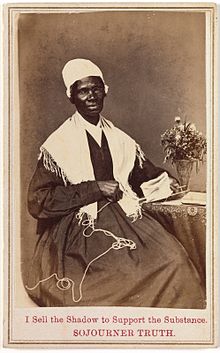

Due to the smaller format and the efficient production of several prints, the costs for portrait photography could be reduced significantly. Around 1880 the price of 2.50 marks for six prints was only the daily wage of a worker. As a result, (portrait) photography quickly developed into an enormous success; In England alone, between 300 and 400 million cartes de visite were produced annually from 1861 to 1867.

In the second half of the 19th century it was common to give away business card portraits and collect them in albums. Business card portraits were also made and sold by celebrities; 70,000 portraits are said to have been sold after the death of the British Prince Consort.

“As portraits, most cards de visite had little aesthetic value. No attempt was made to clarify the character of the person being portrayed by differentiated lighting or by choosing a certain posture or facial expression. "

Today, however, business card portraits are important testimonies for historians and sociologists .

Around 1866, in addition to the business card format, the larger cabinet card (also called cabinet ) was offered, but the small standard format remained the most widely used until the First World War .

The great popularity of business and cabinet cards also led to the development of suitable accessories: picture frames for setting up or hanging, photo albums with corresponding passe-partouts into which the pictures could be inserted were produced and offered in large numbers.

See also

literature

- Matthias Gründig: The Shah in the box. Social image practices in the age of the carte de visite . Jonas Verlag, Marburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-89445-530-9 .

- Gisèle Freund : Photography in the Second Empire (1851–1870) . In: Photography and Society . Rowohlt Tb., 1997, ISBN 978-3-499-17265-6 , pp. 65 ff .

- Jochen Voigt: The fascination of collecting. Cartes de visite. A cultural history of the photographic business card . Edition Mobilis, Chemnitz 2006, ISBN 3-9808878-3-9 .

- Ludwig Hoerner : The photographic industry in Germany. 1839-1914 . GFW-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1989, ISBN 3-87258-000-0 .

- Helmut Gernsheim : Portrait photography - a new industry. Claim and criticism. Pioneer of fine art photography. The cliché verre and the business card portrait. Disdéri and the consequences. Highlights of the "cartomania" . In: ders .: History of Photography. The first hundred years . Propylaea: Frankfurt a. M., Berlin and Vienna 1983, pp. 285-292 and 355-368.

- The introduction of visiting card photography in: Josef Maria Eder : Geschichte der Photographie 1st volume, 4th edition, Verlag Wilhelm Knapp, Halle / Saale, 1932, p. 487ff.

- J. Schnauss : About business card portraits . In: Photographic Archive . tape 2 . Theobald Grieben, Berlin 1861, p. 205-208 .

- Leo Bock: Photographic Thoughts . In: Photographic Archive . tape 3 . Theobald Grieben, Berlin 1862, p. 124–127 (evaluation of the CdV from its early years).

- H. d'Aubigier: About the business card portraits . In: Wilhelm Horn: Photographisches Journal , Volume 15, 1861, Otto Spamer, Leipzig, pp. 15-17.

- Société d'héliographie (ed.): La Lumière . Revue de la Photographie: Beaux-arts, Héliographie, Sciences. Paris (1855–1898) (French), ZDB ID 2861128-7 .

Web links

- Short overview of the history of the carte de visite (English)

- Features of the historical allocation of CDV (English)

- American CDV gallery with assignment of the photographers (English)

- Website for cabinet card photography including portraits of other cabinet card photographers (English)

- museum-digital: Carte de Visite collection

Footnotes

Remarks

- ↑ The magazine was the very first to deal with photography.

- ↑ Louis Dodero (1824-1902), French photographer

- ^ Ernest Lacan (1828–1879), editor-in-chief and publisher of La Lumiere magazine

- ↑ Édouard Delessert (1828–1898), French photographer

- ↑ Olympe Aguado (1827-1894), French photographer

- ^ Under the heading "Correspondenz aus Paris" in the journal Photographisches Archiv (2nd vol., P. 260) the author / correspondent referred in 1861 to these ideas of Mr. Delessert and Aguado. The correspondent was Ernest Lacan, the author of the mentioned articles in La Lumiere .

- ↑ In this context it was repeatedly reported that Napoleon III. rode past Disdéri's studio on May 10, 1859 at the head of an army corps, and a spontaneous recording came about. Jochen Voigt proves in his book (pp. 9–11) that this could not have happened that way. Napoleon III had been portrayed in civilian clothes and with the Empress Eugene . Ernest Lacan wrote in an essay for the Photographic Journal , which was reprinted in Volume 14 from 1860, “One cannot imagine how the local public is viewed with business cards. Everyone wants to own his portrait in this format and distribute it to his friends. Then the portraits of the political, artistic and literary notabilities, of the celebrities of the clergy, the magistrates, the army, the theater and even the demi-monde are printed in thousands of copies and distributed in the trade. "(P. 56)

- ↑ It is possibly the photographer Claude-Marie Ferrier (1811–1889), who is said to have stayed in Nice in 1857 according to the "Union List of Artist Names" of the J. Paul Getty Trust ( online ).

- ↑ It is not clear which Duke of Parma it is, as Duke Robert of Parma was only 9 years old at this point in time and his father had already died.

Individual evidence

- ^ Gisèle Freund: Photography in the Second Empire (1851–1870) . In: Photography and Society . Rowohlt Tb., 1997, ISBN 978-3-499-17265-6 , pp. 68 .

- ↑ a b Jochen Voigt: The fascination of collecting. Cartes de visite. A cultural history of the photographic business card . EditionMobilis, Chemnitz 2006, ISBN 3-9808878-3-9 , p. 12-13 .

- ↑ La Lumiere, August 24, 1851, p. 115.

- ↑ La Lumiere, October 28, 1854. pp. 170-171.

- ^ Benjamin Vincent: Haydn's Dictionary of Dates , 13th Edition, Edward Moxon & Co, London, 1868, p. 152, digitized

- ↑ 79. The common formats of paper images . In: Dr. Josef Marie Eder (Hrsg.): Yearbook for photography and reproduction technology . 3rd year Wilhelm Knapp, Halle / S. 1889, p. 74 .

- ↑ Christa Pieske : The ABC of luxury paper . Manufacture, processing and use 1860–1930. Reimer, Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-496-01023-1 , p. 221 .

- ↑ Timm Starl: Behind the Pictures. For dating and identification of photographs from 1839 to 1945 . In: Photo history . tape 26 , no. 99 . Jonas Verlag, Marburg March 2006, p. 17 .

- ↑ The photo album 1858–1918 . Exhibition catalog, Stadtmuseum München , Munich 1975, pp. 90–94