Jean-François Millet: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 2 edits by 2603:6000:B04C:1E9:FCD6:E4E5:4173:92A1 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG |

m Reverted edit by Anushka Pokharkar (talk) to last version by Modernist |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | |||

{{for|the 19th-century English painter Millais|John Everett Millais}} |

|||

{{short description|French painter (1814–1875)}} |

{{short description|French painter (1814–1875)}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{EngvarB|date=June 2022}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2022}} |

|||

{{Infobox artist |

{{Infobox artist |

||

| name |

| name = Jean-François Millet |

||

| image |

| image = Jean-François Millet by Nadar, Metropolitan Museum copy.jpg |

||

| caption |

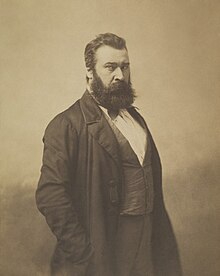

| caption = Portrait by [[Nadar]], {{circa|1856-58}} |

||

| birth_name |

| birth_name = Jean-François Millet |

||

| birth_date |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1814|10|4|df=y}} |

||

| birth_place = |

| birth_place = Gruchy, [[Gréville-Hague]], Normandy, France |

||

| death_date |

| death_date = {{death date and age|1875|1|20|1814|10|4|df=y}} |

||

| death_place = [[Barbizon]], [[Île de France]], France |

| death_place = [[Barbizon]], [[Île de France]], France |

||

| field |

| field = Painting |

||

| training |

| training = |

||

| movement |

| movement = [[Realism (arts)|Realism]] |

||

| works |

| works = |

||

| patrons |

| patrons = |

||

| awards |

| awards = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Jean-François Millet''' ({{IPA-fr|milɛ |

'''Jean-François Millet''' ({{IPA-fr|ʒɑ̃ fʁɑ̃swa milɛ}}; 4 October 1814 – 20 January 1875) was a French artist and one of the founders of the [[Barbizon school]] in rural France. Millet is noted for his paintings of peasant farmers and can be categorized as part of the [[Realism art movement]]. Toward the end of his career, he became increasingly interested in painting pure landscapes. He is known best for his oil paintings but is also noted for his pastels, [[conte crayon|Conté crayon]] drawings, and [[etching]]s. |

||

==Life and work== |

==Life and work== |

||

===Youth=== |

===Youth=== |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Jean-François Millet - The Sheepfold, Moonlight - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|''The Sheepfold''. In this painting by Millet, the waning Moon throws a mysterious light across the plain between the villages of Barbizon and Chailly.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Sheepfold, Moonlight |url=http://art.thewalters.org/detail/24760 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210725002233/http://art.thewalters.org/detail/24760 |archive-date=25 July 2021 |access-date=1 August 2022 |publisher=[[The Walters Art Museum]]}}</ref> The Walters Art Museum.]] |

||

[[File:Jean-François Millet - was a but head |

|||

| ⚫ | Millet was the first child of Jean-Louis-Nicolas and Aimée-Henriette-Adélaïde Henry Millet, members of the farming community in the village of Gruchy, in [[Gréville-Hague]], Normandy, close to the coast.<ref name="Murphy, p.xix">Murphy, p.xix.</ref> Under the guidance of two village priests—one of them was vicar Jean Lebrisseux—Millet acquired a knowledge of Latin and modern authors. But soon he had to help his father with the farm work;<ref>[https://archive.org/details/jeanfranoismil00sens his biographer Alfred Sensier, p. 34]</ref> because Millet was the eldest of the sons. So all the farmer's work was familiar to him: to mow, make hay, bind the sheaves, thresh, winnow, spread manure, plow, sow, etc. All these motifs returned in his later art. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

|url= http://art.thewalters.org/detail/24760 |

|||

|title= The Sheepfold, Moonlight}}</ref> The Walters Art Museum.]] |

|||

| ⚫ | Millet was the first child of Jean-Louis-Nicolas and Aimée-Henriette-Adélaïde Henry Millet, members of the farming community in the village of |

||

In 1833 his father sent him to [[Cherbourg]] to study with a portrait painter named Bon Du Mouchel.<ref name="GroveArtOnline"/> By 1835 he was studying with [[:fr:Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville|Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville]],<ref name="GroveArtOnline">McPherson, H. |

In 1833, his father sent him to [[Cherbourg]] to study with a portrait painter named Bon Du Mouchel.<ref name="GroveArtOnline"/> By 1835 he was studying with [[:fr:Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville|Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville]],<ref name="GroveArtOnline">McPherson, H. (2003). Millet, Jean-François. ''Grove Art Online''.</ref> a pupil of [[Baron Gros]], in [[Cherbourg-Octeville|Cherbourg]]. A stipend provided by Langlois and others enabled Millet to move to Paris in 1837, where he studied at the [[École des Beaux-Arts]] with [[Paul Delaroche]].<ref name=HF>Honour, H. and J. Fleming, p. 669.</ref> In 1839, his scholarship was terminated, and his first submission to the [[Paris Salon|Salon]], ''Saint Anne Instructing the Virgin'', was rejected by the jury.<ref name="Pollock_21">Pollock, p. 21.</ref> |

||

===Paris=== |

===Paris=== |

||

[[Image:Jean-François Millet (II) 005.jpg|thumb|''Woman Baking Bread'', 1854. [[Kröller-Müller Museum]], [[Otterlo]].]] |

[[Image:Jean-François Millet (II) 005.jpg|thumb|''Woman Baking Bread'', 1854. [[Kröller-Müller Museum]], [[Otterlo]].]] |

||

After his first painting, a portrait, was accepted at the Salon of 1840, Millet returned to Cherbourg to begin a career as a [[portrait painter]].<ref name="Pollock_21"/> |

After his first painting, a portrait, was accepted at the Salon of 1840, Millet returned to Cherbourg to begin a career as a [[portrait painter]].<ref name="Pollock_21"/> The following year he married Pauline-Virginie Ono, and they moved to [[Paris]]. After rejections at the Salon of 1843 and Pauline's death by [[Tuberculosis|consumption]] in April 1844, Millet returned again to Cherbourg.<ref name="Pollock_21"/> In 1845, Millet moved to [[Le Havre]] with Catherine Lemaire, whom he married in a civil ceremony in 1853; they had nine children and remained together for the rest of Millet's life.<ref>Murphy, p.21.</ref> In Le Havre he painted portraits and small genre pieces for several months, before moving back to Paris. |

||

It was in Paris in the middle 1840s that Millet befriended [[Constant Troyon]], [[Narcisse Diaz]], [[Charles Jacque]], and [[Théodore Rousseau]], artists who, like Millet, became associated with the Barbizon school; [[Honoré Daumier]], whose figure draftsmanship influenced Millet's subsequent rendering of peasant subjects; and [[:fr:Alfred Sensier]], a government bureaucrat who became a lifelong supporter and eventually the artist's biographer.<ref>Champa, p.183.</ref> In 1847 his first Salon success came with the exhibition of a painting ''Oedipus Taken down from the Tree'', and in 1848 his ''Winnower'' was bought by the government.<ref name="Pollock_22">Pollock, p. 22.</ref> |

It was in Paris in the middle 1840s that Millet befriended [[Constant Troyon]], [[Narcisse Diaz]], [[Charles Jacque]], and [[Théodore Rousseau]], artists who, like Millet, became associated with the Barbizon school; [[Honoré Daumier]], whose figure draftsmanship influenced Millet's subsequent rendering of peasant subjects; and [[:fr:Alfred Sensier]], a government bureaucrat who became a lifelong supporter and eventually the artist's biographer.<ref>Champa, p.183.</ref> In 1847, his first Salon success came with the exhibition of a painting ''Oedipus Taken down from the Tree'', and in 1848, his ''Winnower'' was bought by the government.<ref name="Pollock_22">Pollock, p. 22.</ref> |

||

''The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon'', Millet's most ambitious work at the time, was unveiled at the Salon of 1848, but was scorned by art critics and the public alike. The painting eventually disappeared shortly thereafter, leading historians to believe that Millet destroyed it. In 1984, scientists at the [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston|Museum of Fine Arts in Boston]] x-rayed Millet's 1870 painting ''The Young Shepherdess'' looking for minor changes, and discovered that it was painted over ''Captivity''. It is now believed that Millet reused the canvas when materials were in short supply during the [[Franco-Prussian War]]. |

''The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon'', Millet's most ambitious work at the time, was unveiled at the Salon of 1848, but was scorned by art critics and the public alike. The painting eventually disappeared shortly thereafter, leading historians to believe that Millet destroyed it. In 1984, scientists at the [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston|Museum of Fine Arts in Boston]] x-rayed Millet's 1870 painting ''The Young Shepherdess'' looking for minor changes, and discovered that it was painted over ''Captivity''. It is now believed that Millet reused the canvas when materials were in short supply during the [[Franco-Prussian War]]. |

||

| Line 44: | Line 42: | ||

[[File:HarvestersRestingRuthBoazMillet.jpg|thumb|left|''Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)'', [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]] (1850–1853)]] |

[[File:HarvestersRestingRuthBoazMillet.jpg|thumb|left|''Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)'', [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]] (1850–1853)]] |

||

In 1850 Millet entered into an arrangement with Sensier, who provided the artist with materials and money in return for drawings and paintings, while Millet simultaneously was free to continue selling work to other buyers as well.<ref>Murphy, p. xix.</ref> At that year's Salon, he exhibited ''Haymakers'' and ''The Sower'', his first major masterpiece and the earliest of the iconic trio of paintings that included ''The Gleaners'' and ''The Angelus''.<ref>Murphy, p.31.</ref> |

In 1850, Millet entered into an arrangement with Sensier, who provided the artist with materials and money in return for drawings and paintings, while Millet simultaneously was free to continue selling work to other buyers as well.<ref>Murphy, p. xix.</ref> At that year's Salon, he exhibited ''Haymakers'' and ''The Sower'', his first major masterpiece and the earliest of the iconic trio of paintings that included ''The Gleaners'' and ''The Angelus''.<ref>Murphy, p.31.</ref> |

||

From 1850 to 1853, Millet worked on ''Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/harvesters-resting-ruth-and-boaz-31288|title=Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)|date=29 January 2018}}</ref> a painting he considered his most important, and on which he worked the longest. Conceived to rival his heroes [[Michelangelo]] and [[Poussin]], it was also the painting that marked his transition from the depiction of symbolic imagery of peasant life to that of contemporary social conditions. It was the only painting he ever dated, and was the first work to garner him official recognition, a second-class medal at the 1853 salon.<ref>Murphy, p. 60</ref> |

From 1850 to 1853, Millet worked on ''Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/harvesters-resting-ruth-and-boaz-31288|title=Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)|date=29 January 2018}}</ref> a painting he considered his most important, and on which he worked the longest. Conceived to rival his heroes [[Michelangelo]] and [[Poussin]], it was also the painting that marked his transition from the depiction of symbolic imagery of peasant life to that of contemporary social conditions. It was the only painting he ever dated, and was the first work to garner him official recognition, a second-class medal at the 1853 salon.<ref>Murphy, p. 60</ref> |

||

| Line 55: | Line 53: | ||

This is one of the most well known of Millet's paintings, ''[[The Gleaners]]'' (1857). While Millet was walking the fields around Barbizon, one theme returned to his pencil and brush for seven years—[[gleaning]]—the centuries-old right of poor women and children to remove the bits of grain left in the fields following the harvest. He found the theme an eternal one, linked to stories from the Old Testament. In 1857, he submitted the painting ''The Gleaners'' to the Salon to an unenthusiastic, even hostile, public. |

This is one of the most well known of Millet's paintings, ''[[The Gleaners]]'' (1857). While Millet was walking the fields around Barbizon, one theme returned to his pencil and brush for seven years—[[gleaning]]—the centuries-old right of poor women and children to remove the bits of grain left in the fields following the harvest. He found the theme an eternal one, linked to stories from the Old Testament. In 1857, he submitted the painting ''The Gleaners'' to the Salon to an unenthusiastic, even hostile, public. |

||

(Earlier versions include a vertical composition painted in 1854, an etching of 1855–56 which directly presaged the horizontal format of the painting now in the Musée d'Orsay.<ref>Murphy, p. 103.</ref>) |

(Earlier versions include a vertical composition painted in 1854, an etching of 1855–56 which directly presaged the horizontal format of the painting now in the [[Musée d'Orsay]].<ref>Murphy, p. 103.</ref>) |

||

A warm golden light suggests something sacred and eternal in this daily scene where the struggle to survive takes place. During his years of preparatory studies, Millet contemplated how best to convey the sense of repetition and fatigue in the peasants' daily lives. Lines traced over each woman's back lead to the ground and then back up in a repetitive motion identical to their unending, backbreaking labor. Along the horizon, the setting sun silhouettes the farm with its abundant stacks of grain, in contrast to the large shadowy figures in the foreground. The dark homespun dresses of the gleaners cut robust forms against the golden field, giving each woman a noble, monumental strength. |

A warm golden light suggests something sacred and eternal in this daily scene where the struggle to survive takes place. During his years of preparatory studies, Millet contemplated how best to convey the sense of repetition and fatigue in the peasants' daily lives. Lines traced over each woman's back lead to the ground and then back up in a repetitive motion identical to their unending, backbreaking labor. Along the horizon, the setting sun silhouettes the farm with its abundant stacks of grain, in contrast to the large shadowy figures in the foreground. The dark homespun dresses of the gleaners cut robust forms against the golden field, giving each woman a noble, monumental strength. |

||

| Line 61: | Line 59: | ||

====''The Angelus''==== |

====''The Angelus''==== |

||

{{main|The Angelus (painting)}} |

{{main|The Angelus (painting)}} |

||

[[Image:JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET - El Ángelus (Museo de Orsay, 1857-1859. Óleo sobre lienzo, 55.5 x 66 cm).jpg|thumb|left|''The Angelus'', 1857–1859, [[Musée d'Orsay]], Paris]] |

[[Image:JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET - El Ángelus (Museo de Orsay, 1857-1859. Óleo sobre lienzo, 55.5 x 66 cm).jpg|thumb|left|''The Angelus'', 1857–1859, [[Musée d'Orsay]], Paris.]] |

||

The painting was commissioned by Thomas Gold Appleton, an American [[art collector]] based in [[Boston, Massachusetts |

The painting was commissioned by Thomas Gold Appleton, an American [[art collector]] based in [[Boston]], Massachusetts. Appleton previously studied with Millet's friend, the Barbizon painter [[Constant Troyon]]. It was completed during the summer of 1857. Millet added a steeple and changed the initial title of the work, ''Prayer for the Potato Crop'' to ''The Angelus'' when the purchaser failed to take possession of it in 1859. Displayed to the public for the first time in 1865, the painting changed hands several times, increasing only modestly in value, since some considered the artist's political sympathies suspect. Upon Millet's death a decade later, a bidding war between the US and France ensued, ending some years later with a price tag of 800,000 gold francs. |

||

The disparity between the apparent value of the painting and the poor estate of Millet's surviving family was a major impetus in the invention of the [[droit de suite]], intended to compensate artists or their heirs when works are resold.<ref>Stokes, p. 77.</ref> |

The disparity between the apparent value of the painting and the poor estate of Millet's surviving family was a major impetus in the invention of the {{lang|fr|[[droit de suite]]}}, intended to compensate artists or their heirs when works are resold.<ref>Stokes, p. 77.</ref> |

||

===Later years=== |

===Later years=== |

||

[[File:Millet, Jean-François II - Hunting Birds at Night.jpg|thumb|''Hunting Birds at Night'', 1874, [[Philadelphia Museum of Art]].]] |

[[File:Millet, Jean-François II - Hunting Birds at Night.jpg|thumb|''Hunting Birds at Night'', 1874, [[Philadelphia Museum of Art]].]] |

||

[[File:Jean-François Millet, Calling Home the Cows, c. 1866, NGA 168820.jpg|thumb|left|''Calling Home the Cows'', c. 1866, [[National Gallery of Art]]]] |

[[File:Jean-François Millet, Calling Home the Cows, c. 1866, NGA 168820.jpg|thumb|left|''Calling Home the Cows'', c. 1866, [[National Gallery of Art]].]] |

||

Despite mixed reviews of the paintings he exhibited at the Salon, Millet's reputation and success grew |

Despite mixed reviews of the paintings he exhibited at the Salon, Millet's reputation and success grew throughout the 1860s. At the beginning of the decade, he contracted to paint 25 works in return for a monthly stipend for the next three years and in 1865, another patron, Emile Gavet, began commissioning pastels for a collection that eventually included 90 works.<ref name="Murphy, p. xx">Murphy, p. xx.</ref> In 1867, the [[Exposition Universelle (1867)|Exposition Universelle]] hosted a major showing of his work, with the ''Gleaners'', ''Angelus'', and ''Potato Planters'' among the paintings exhibited. The following year, Frédéric Hartmann commissioned ''Four Seasons'' for 25,000 francs, and Millet was named [[Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur]].<ref name="Murphy, p. xx"/> |

||

In 1870, Millet was elected to the Salon jury. Later that year, he and his family fled the [[Franco-Prussian War]], moving to Cherbourg and Gréville, and did not return to Barbizon until late in 1871. His last years were marked by financial success and increased official recognition, but he was unable to fulfill government commissions due to failing health. On January |

In 1870, Millet was elected to the Salon jury. Later that year, he and his family fled the [[Franco-Prussian War]], moving to Cherbourg and Gréville, and did not return to Barbizon until late in 1871. His last years were marked by financial success and increased official recognition, but he was unable to fulfill government commissions due to failing health. On 3 January 1875, he married Catherine in a religious ceremony. Millet died on 20 January 1875.<ref name="Murphy, p. xx"/> |

||

==Legacy== |

==Legacy== |

||

[[Image:Jean-François Millet - The Potato Harvest - Walters 37115.jpg|right|thumb|''[[The Potato Harvest (painting)|The Potato Harvest]]'' (1855)<ref>{{cite web |publisher= [[The Walters Art Museum]] |

[[Image:Jean-François Millet - The Potato Harvest - Walters 37115.jpg|right|thumb|''[[The Potato Harvest (painting)|The Potato Harvest]]'' (1855).<ref>{{cite web |publisher= [[The Walters Art Museum]] |

||

|url= http://art.thewalters.org/detail/22652 |

|url= http://art.thewalters.org/detail/22652 |

||

|title= The Potato Harvest}}</ref> The Walters Art Museum.]] |

|title= The Potato Harvest}}</ref> The Walters Art Museum.]] |

||

| Line 84: | Line 82: | ||

Millet is the main protagonist of [[Mark Twain]]'s play ''[[Is He Dead?]]'' (1898), in which he is depicted as a struggling young artist who fakes his death to score fame and fortune. Most of the details about Millet in the play are fictional. |

Millet is the main protagonist of [[Mark Twain]]'s play ''[[Is He Dead?]]'' (1898), in which he is depicted as a struggling young artist who fakes his death to score fame and fortune. Most of the details about Millet in the play are fictional. |

||

Millet's painting ''L'homme à la houe'' inspired the famous poem "[[The Man With the Hoe]]" (1898) by [[Edwin Markham]]. His |

Millet's painting ''[[L'homme à la houe]]'' inspired the famous poem "[[The Man With the Hoe]]" (1898) by [[Edwin Markham]]. His paintings also served as the inspiration for American poet David Middleton's collection ''The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet'' (2005).<ref>Tadie, ''Poetry and Peace'', Modern Age (2009, Vol. 51:3)</ref> |

||

The ''Angelus'' was reproduced frequently in the 19th and 20th centuries. [[Salvador Dalí]] was fascinated by this work, and wrote an analysis of it, ''The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet''. Rather than seeing it as a work of spiritual peace, Dalí believed it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dalí was also of the opinion that the two figures were praying over their buried child, rather than to the [[Angelus]]. Dalí was so insistent on this fact that eventually an X-ray was done of the canvas, confirming his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin.<ref>Néret, 2000</ref> However, it is unclear whether Millet changed his mind on the meaning of the painting, or even if the shape actually is a coffin. |

The ''Angelus'' was reproduced frequently in the 19th and 20th centuries. [[Salvador Dalí]] was fascinated by this work, and wrote an analysis of it, ''The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet''. Rather than seeing it as a work of spiritual peace, Dalí believed it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dalí was also of the opinion that the two figures were praying over their buried child, rather than to the [[Angelus]]. Dalí was so insistent on this fact that eventually an [[X-ray]] was done of the canvas, confirming his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin.<ref>Néret, 2000</ref> However, it is unclear whether Millet changed his mind on the meaning of the painting, or even if the shape actually is a coffin. |

||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<gallery widths=" |

<gallery widths="180" heights="180" perrow="4" caption="Jean-François Millet's paintings"> |

||

File:1841, Millet, Jean-François, Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles.jpg|''Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles'', 1841, [[Princeton University Art Museum]] |

File:1841, Millet, Jean-François, Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles.jpg|''Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles'', 1841, [[Princeton University Art Museum]] |

||

File:The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Jean-François Millet.png|''The Abduction of the Sabine Women'' by Jean-François Millet, c.1844–1847 |

File:The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Jean-François Millet.png|''The Abduction of the Sabine Women'' by Jean-François Millet, c.1844–1847 |

||

File:Going to Work by Jean-François Millet, 1851-53.jpg|''Going to Work'', 1851–1853 |

File:Going to Work by Jean-François Millet, 1851-53.jpg|''Going to Work'', 1851–1853 |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - Femme filature (1855-60).jpg|''Woman Spinning (The Spinning Wheel)'', c. 1855-60. [[Clark Art Institute]] |

|||

File:Mille - Shepherdess Seated on a Rock - Metropolitan.jpg|''[[Shepherdess Seated on a Rock]]'', 1856 |

File:Mille - Shepherdess Seated on a Rock - Metropolitan.jpg|''[[Shepherdess Seated on a Rock]]'', 1856 |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - Apport à la maison le veau né dans les champs (1860).jpg|''Bringing home the calf born in the fields'', c. 1860, [[Princeton University Art Museum]] |

File:Jean-François Millet - Apport à la maison le veau né dans les champs (1860).jpg|''Bringing home the calf born in the fields'', c. 1860, [[Princeton University Art Museum]] |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - Shepherd Tending His Flock - Google Art Project.jpg|''Shepherd Tending His Flock'', early 1860s |

File:Jean-François Millet - Shepherd Tending His Flock - Google Art Project.jpg|''Shepherd Tending His Flock'', early 1860s |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - |

File:Jean-François Millet - La leçon à tricoter.jpg|''The Knitting Lesson'', c. 1860. [[Clark Art Institute]] |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - Potato Planters - Google Art Project.jpg|''Potato Planters'', 1861 |

|||

File:Jean-François Millet - The Goose Girl - Walters 37153.jpg|''The Goose Girl'', 1863 |

File:Jean-François Millet - The Goose Girl - Walters 37153.jpg|''The Goose Girl'', 1863 |

||

File:Jean-François Millet Pastora.jpg|''[[Shepherdess with her Flock]]'', 1864 |

File:Jean-François Millet Pastora.jpg|''[[Shepherdess with her Flock]]'', 1864 |

||

File: |

File:The Sower- Jean-François Millet.jpg|''The Sower'', c. 1865. [[Clark Art Institute]] |

||

File:Haystacks Autumn 1873 Jean-Francois Millet.jpg|''[[Haystacks: Autumn]]'', c. 1874, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art |

|||

File:Millet Gréville.JPG|'' The Coast of Gréville'', undated [[Nationalmuseum|National Museum, Stockholm]] |

File:Millet Gréville.JPG|'' The Coast of Gréville'', undated [[Nationalmuseum|National Museum, Stockholm]] |

||

File:Jean-François Millet - Jeune fille gardant ses moutons (1860-62).jpg|''Young Girl Guarding her Sheep'', c. 1860-62. [[Clark Art Institute]] |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 110: | Line 112: | ||

* [[Hugh Honour|Honour, H.]] and Fleming, J. ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2009. {{ISBN|9781856695848}} |

* [[Hugh Honour|Honour, H.]] and Fleming, J. ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2009. {{ISBN|9781856695848}} |

||

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. ''Catalogue raisonné Jean-François Millet'' en 2 volumes – Paris 1971 / 1973 |

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. ''Catalogue raisonné Jean-François Millet'' en 2 volumes – Paris 1971 / 1973 |

||

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. |

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. "Le Viquet – Retour sur les premiers pas : un Millet inconnu" – N° 139 Paques 2003. {{ISSN|0764-7948}} |

||

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. |

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. ''Jean François Millet (Au delà de l'Angélus)'' – Ed de Monza – 2002 – ({{ISBN|2-908071-93-2}}) |

||

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. |

* Lepoittevin, Lucien. ''Jean François Millet : Images et symboles'', Éditions Isoète Cherbourg 1990. ({{ISBN|2-905385-32-4}}) |

||

* Moreau-Nélaton, E. ''Monographie de reference, Millet raconté par lui-même'' – 3 volumes – Paris 1921 |

* Moreau-Nélaton, E. ''Monographie de reference, Millet raconté par lui-même'' – 3 volumes – Paris 1921 |

||

* Murphy, Alexandra R. ''Jean-François Millet''. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1984. {{ISBN|0-87846-237-6}} |

* Murphy, Alexandra R. ''Jean-François Millet''. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1984. {{ISBN|0-87846-237-6}} |

||

* Plaideux, Hugues. "L'inventaire après décès et la déclaration de succession de Jean-François Millet", in ''Revue de la Manche'', t. 53, fasc. 212, 2e trim. 2011, p. 2–38. |

* Plaideux, Hugues. "L'inventaire après décès et la déclaration de succession de Jean-François Millet", in ''Revue de la Manche'', t. 53, fasc. 212, 2e trim. 2011, p. 2–38. |

||

* Plaideux, Hugues. "Une enseigne de vétérinaire cherbourgeois peinte par Jean-François Millet en 1841", in ''Bulletin de la Société française d'histoire de la médecine et des sciences vétérinaires'', n° 11, 2011, p. 61–75. |

* Plaideux, Hugues. "Une enseigne de vétérinaire cherbourgeois peinte par Jean-François Millet en 1841", in ''Bulletin de la Société française d'histoire de la médecine et des sciences vétérinaires'', n° 11, 2011, p. 61–75. |

||

* Pollock, Griselda. ''Millet''. London: Oresko, 1977. {{ISBN|0905368134}}. |

* [[Griselda Pollock|Pollock, Griselda]]. ''Millet''. London: Oresko, 1977. {{ISBN|0905368134}}. |

||

* Stokes, Simon. ''Art and Copyright''. Hart Publishing, 2001. {{ISBN|1-84113-225-X}} |

* Stokes, Simon. ''Art and Copyright''. Hart Publishing, 2001. {{ISBN|1-84113-225-X}} |

||

* Tadie, Andrew. [https://home.isi.org/poetry-and-peace-ithe-habitual-peacefulness-gruchy-poems-after-pictures-jean-fran%C3%A7ois-milleti-david Poetry and Peace: The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet by David Middleton]. ''Modern Age: A Quarterly Review''. Summer/Fall 2009 (Vol. 51:3) |

* Tadie, Andrew. [https://home.isi.org/poetry-and-peace-ithe-habitual-peacefulness-gruchy-poems-after-pictures-jean-fran%C3%A7ois-milleti-david Poetry and Peace: The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet by David Middleton] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181214112016/https://home.isi.org/poetry-and-peace-ithe-habitual-peacefulness-gruchy-poems-after-pictures-jean-fran%C3%A7ois-milleti-david |date=14 December 2018 }}. ''Modern Age: A Quarterly Review''. Summer/Fall 2009 (Vol. 51:3) |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons |

{{Commons|Paintings by Jean-François Millet (II)}} |

||

{{Wikiquote}} |

{{Wikiquote}} |

||

* [http://www.jeanmillet.org jeanmillet.org]; 125 works by Jean-François Millet |

* [http://www.jeanmillet.org jeanmillet.org]; 125 works by Jean-François Millet |

||

| Line 130: | Line 132: | ||

* [https://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A585344 Influence on Dali] – grieving parents or praying peasants in ''The Angelus''? |

* [https://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A585344 Influence on Dali] – grieving parents or praying peasants in ''The Angelus''? |

||

* {{Cite CE1913 |last=Gillet |first=Louis |authorlink=Louis Gillet |wstitle=Jean-François Millet |short=x}} |

* {{Cite CE1913 |last=Gillet |first=Louis |authorlink=Louis Gillet |wstitle=Jean-François Millet |short=x}} |

||

* {{Cite EB1911 |volume= 18 | pages = |

* {{Cite EB1911 |volume= 18 | pages = 466–467 |last= Dilke |first= Emilia Francis Strong |authorlink= Emilia, Lady Dilke |wstitle=Millet, Jean François (1814–1875) |short=x}} |

||

* "[[s:Jean-François Millet (Coates)|Jean-François Millet]]", poem by [[Florence Earle Coates]] |

* "[[s:Jean-François Millet (Coates)|Jean-François Millet]]", poem by [[Florence Earle Coates]] |

||

* Cartwright, Julia, (1902) [https://archive.org/stream/jeanfrancoismill00cart#page/n5/mode/2up ''Jean François Millet: his life and letters |

* Cartwright, Julia, (1902) [https://archive.org/stream/jeanfrancoismill00cart#page/n5/mode/2up ''Jean François Millet: his life and letters''] London: Swan Sonnenschein and Co. |

||

* Sensier, Alfred, (1881) [https://archive.org/details/jeanfranoismil00sens?q=sensier ''Jean-Francois Millet – Peasant and Painter''] (transl. Helena de Kay) London: Macmillan and Co. |

* Sensier, Alfred, (1881) [https://archive.org/details/jeanfranoismil00sens?q=sensier ''Jean-Francois Millet – Peasant and Painter''] (transl. Helena de Kay) London: Macmillan and Co. |

||

{{Jean-François Millet}} |

{{Jean-François Millet}} |

||

{{Authority control (arts)}} |

|||

{{ACArt}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Millet, Jean-Francois}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Millet, Jean-Francois}} |

||

| Line 142: | Line 144: | ||

[[Category:1875 deaths]] |

[[Category:1875 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:People from Manche]] |

[[Category:People from Manche]] |

||

[[Category:Artists from Normandy]] |

|||

[[Category:French Realist painters]] |

[[Category:French Realist painters]] |

||

[[Category:19th-century French painters]] |

[[Category:19th-century French painters]] |

||

[[Category:French male painters]] |

[[Category:French male painters]] |

||

[[Category:19th-century French male artists]] |

|||

[[Category:French pastel artists]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 12:34, 7 February 2024

Jean-François Millet | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Nadar, c. 1856-58 | |

| Born | Jean-François Millet 4 October 1814 Gruchy, Gréville-Hague, Normandy, France |

| Died | 20 January 1875 (aged 60) Barbizon, Île de France, France |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Realism |

Jean-François Millet (French pronunciation: [ʒɑ̃ fʁɑ̃swa milɛ]; 4 October 1814 – 20 January 1875) was a French artist and one of the founders of the Barbizon school in rural France. Millet is noted for his paintings of peasant farmers and can be categorized as part of the Realism art movement. Toward the end of his career, he became increasingly interested in painting pure landscapes. He is known best for his oil paintings but is also noted for his pastels, Conté crayon drawings, and etchings.

Life and work[edit]

Youth[edit]

Millet was the first child of Jean-Louis-Nicolas and Aimée-Henriette-Adélaïde Henry Millet, members of the farming community in the village of Gruchy, in Gréville-Hague, Normandy, close to the coast.[2] Under the guidance of two village priests—one of them was vicar Jean Lebrisseux—Millet acquired a knowledge of Latin and modern authors. But soon he had to help his father with the farm work;[3] because Millet was the eldest of the sons. So all the farmer's work was familiar to him: to mow, make hay, bind the sheaves, thresh, winnow, spread manure, plow, sow, etc. All these motifs returned in his later art.

In 1833, his father sent him to Cherbourg to study with a portrait painter named Bon Du Mouchel.[4] By 1835 he was studying with Théophile Langlois de Chèvreville,[4] a pupil of Baron Gros, in Cherbourg. A stipend provided by Langlois and others enabled Millet to move to Paris in 1837, where he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts with Paul Delaroche.[5] In 1839, his scholarship was terminated, and his first submission to the Salon, Saint Anne Instructing the Virgin, was rejected by the jury.[6]

Paris[edit]

After his first painting, a portrait, was accepted at the Salon of 1840, Millet returned to Cherbourg to begin a career as a portrait painter.[6] The following year he married Pauline-Virginie Ono, and they moved to Paris. After rejections at the Salon of 1843 and Pauline's death by consumption in April 1844, Millet returned again to Cherbourg.[6] In 1845, Millet moved to Le Havre with Catherine Lemaire, whom he married in a civil ceremony in 1853; they had nine children and remained together for the rest of Millet's life.[7] In Le Havre he painted portraits and small genre pieces for several months, before moving back to Paris.

It was in Paris in the middle 1840s that Millet befriended Constant Troyon, Narcisse Diaz, Charles Jacque, and Théodore Rousseau, artists who, like Millet, became associated with the Barbizon school; Honoré Daumier, whose figure draftsmanship influenced Millet's subsequent rendering of peasant subjects; and fr:Alfred Sensier, a government bureaucrat who became a lifelong supporter and eventually the artist's biographer.[8] In 1847, his first Salon success came with the exhibition of a painting Oedipus Taken down from the Tree, and in 1848, his Winnower was bought by the government.[9]

The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon, Millet's most ambitious work at the time, was unveiled at the Salon of 1848, but was scorned by art critics and the public alike. The painting eventually disappeared shortly thereafter, leading historians to believe that Millet destroyed it. In 1984, scientists at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston x-rayed Millet's 1870 painting The Young Shepherdess looking for minor changes, and discovered that it was painted over Captivity. It is now believed that Millet reused the canvas when materials were in short supply during the Franco-Prussian War.

Barbizon[edit]

In 1849, Millet painted Harvesters, a commission for the state. In the Salon of that year, he exhibited Shepherdess Sitting at the Edge of the Forest, a very small oil painting which marked a turning away from previous idealized pastoral subjects, in favor of a more realistic and personal approach.[10] In June of that year, he settled in Barbizon with Catherine and their children.

In 1850, Millet entered into an arrangement with Sensier, who provided the artist with materials and money in return for drawings and paintings, while Millet simultaneously was free to continue selling work to other buyers as well.[11] At that year's Salon, he exhibited Haymakers and The Sower, his first major masterpiece and the earliest of the iconic trio of paintings that included The Gleaners and The Angelus.[12]

From 1850 to 1853, Millet worked on Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz),[13] a painting he considered his most important, and on which he worked the longest. Conceived to rival his heroes Michelangelo and Poussin, it was also the painting that marked his transition from the depiction of symbolic imagery of peasant life to that of contemporary social conditions. It was the only painting he ever dated, and was the first work to garner him official recognition, a second-class medal at the 1853 salon.[14]

In the mid-1850s, Millet produced a small number of etchings of peasant subjects, such as Man with a Wheelbarrow (1855) and Woman Carding Wool (1855–1857).[15]

The Gleaners[edit]

This is one of the most well known of Millet's paintings, The Gleaners (1857). While Millet was walking the fields around Barbizon, one theme returned to his pencil and brush for seven years—gleaning—the centuries-old right of poor women and children to remove the bits of grain left in the fields following the harvest. He found the theme an eternal one, linked to stories from the Old Testament. In 1857, he submitted the painting The Gleaners to the Salon to an unenthusiastic, even hostile, public.

(Earlier versions include a vertical composition painted in 1854, an etching of 1855–56 which directly presaged the horizontal format of the painting now in the Musée d'Orsay.[16])

A warm golden light suggests something sacred and eternal in this daily scene where the struggle to survive takes place. During his years of preparatory studies, Millet contemplated how best to convey the sense of repetition and fatigue in the peasants' daily lives. Lines traced over each woman's back lead to the ground and then back up in a repetitive motion identical to their unending, backbreaking labor. Along the horizon, the setting sun silhouettes the farm with its abundant stacks of grain, in contrast to the large shadowy figures in the foreground. The dark homespun dresses of the gleaners cut robust forms against the golden field, giving each woman a noble, monumental strength.

The Angelus[edit]

The painting was commissioned by Thomas Gold Appleton, an American art collector based in Boston, Massachusetts. Appleton previously studied with Millet's friend, the Barbizon painter Constant Troyon. It was completed during the summer of 1857. Millet added a steeple and changed the initial title of the work, Prayer for the Potato Crop to The Angelus when the purchaser failed to take possession of it in 1859. Displayed to the public for the first time in 1865, the painting changed hands several times, increasing only modestly in value, since some considered the artist's political sympathies suspect. Upon Millet's death a decade later, a bidding war between the US and France ensued, ending some years later with a price tag of 800,000 gold francs.

The disparity between the apparent value of the painting and the poor estate of Millet's surviving family was a major impetus in the invention of the droit de suite, intended to compensate artists or their heirs when works are resold.[17]

Later years[edit]

Despite mixed reviews of the paintings he exhibited at the Salon, Millet's reputation and success grew throughout the 1860s. At the beginning of the decade, he contracted to paint 25 works in return for a monthly stipend for the next three years and in 1865, another patron, Emile Gavet, began commissioning pastels for a collection that eventually included 90 works.[18] In 1867, the Exposition Universelle hosted a major showing of his work, with the Gleaners, Angelus, and Potato Planters among the paintings exhibited. The following year, Frédéric Hartmann commissioned Four Seasons for 25,000 francs, and Millet was named Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur.[18]

In 1870, Millet was elected to the Salon jury. Later that year, he and his family fled the Franco-Prussian War, moving to Cherbourg and Gréville, and did not return to Barbizon until late in 1871. His last years were marked by financial success and increased official recognition, but he was unable to fulfill government commissions due to failing health. On 3 January 1875, he married Catherine in a religious ceremony. Millet died on 20 January 1875.[18]

Legacy[edit]

Millet was an important source of inspiration for Vincent van Gogh, particularly during his early period. Millet and his work are mentioned many times in Vincent's letters to his brother Theo. Millet's late landscapes served as influential points of reference to Claude Monet's paintings of the coast of Normandy; his structural and symbolic content influenced Georges Seurat as well.[20]

Millet is the main protagonist of Mark Twain's play Is He Dead? (1898), in which he is depicted as a struggling young artist who fakes his death to score fame and fortune. Most of the details about Millet in the play are fictional.

Millet's painting L'homme à la houe inspired the famous poem "The Man With the Hoe" (1898) by Edwin Markham. His paintings also served as the inspiration for American poet David Middleton's collection The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet (2005).[21]

The Angelus was reproduced frequently in the 19th and 20th centuries. Salvador Dalí was fascinated by this work, and wrote an analysis of it, The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet. Rather than seeing it as a work of spiritual peace, Dalí believed it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dalí was also of the opinion that the two figures were praying over their buried child, rather than to the Angelus. Dalí was so insistent on this fact that eventually an X-ray was done of the canvas, confirming his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin.[22] However, it is unclear whether Millet changed his mind on the meaning of the painting, or even if the shape actually is a coffin.

Gallery[edit]

- Jean-François Millet's paintings

-

Portrait of Louis-Alexandre Marolles, 1841, Princeton University Art Museum

-

The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Jean-François Millet, c.1844–1847

-

Going to Work, 1851–1853

-

Woman Spinning (The Spinning Wheel), c. 1855-60. Clark Art Institute

-

Bringing home the calf born in the fields, c. 1860, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Shepherd Tending His Flock, early 1860s

-

The Knitting Lesson, c. 1860. Clark Art Institute

-

Potato Planters, 1861

-

The Goose Girl, 1863

-

The Sower, c. 1865. Clark Art Institute

-

Haystacks: Autumn, c. 1874, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Coast of Gréville, undated National Museum, Stockholm

-

Young Girl Guarding her Sheep, c. 1860-62. Clark Art Institute

Notes[edit]

- ^ "The Sheepfold, Moonlight". The Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Murphy, p.xix.

- ^ his biographer Alfred Sensier, p. 34

- ^ a b McPherson, H. (2003). Millet, Jean-François. Grove Art Online.

- ^ Honour, H. and J. Fleming, p. 669.

- ^ a b c Pollock, p. 21.

- ^ Murphy, p.21.

- ^ Champa, p.183.

- ^ Pollock, p. 22.

- ^ Murphy, p.23.

- ^ Murphy, p. xix.

- ^ Murphy, p.31.

- ^ "Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz)". 29 January 2018.

- ^ Murphy, p. 60

- ^ Pollock, p. 58.

- ^ Murphy, p. 103.

- ^ Stokes, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Murphy, p. xx.

- ^ "The Potato Harvest". The Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Champa, p. 184.

- ^ Tadie, Poetry and Peace, Modern Age (2009, Vol. 51:3)

- ^ Néret, 2000

References[edit]

- Champa, Kermit S. The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-8109-3757-3

- Honour, H. and Fleming, J. A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2009. ISBN 9781856695848

- Lepoittevin, Lucien. Catalogue raisonné Jean-François Millet en 2 volumes – Paris 1971 / 1973

- Lepoittevin, Lucien. "Le Viquet – Retour sur les premiers pas : un Millet inconnu" – N° 139 Paques 2003. ISSN 0764-7948

- Lepoittevin, Lucien. Jean François Millet (Au delà de l'Angélus) – Ed de Monza – 2002 – (ISBN 2-908071-93-2)

- Lepoittevin, Lucien. Jean François Millet : Images et symboles, Éditions Isoète Cherbourg 1990. (ISBN 2-905385-32-4)

- Moreau-Nélaton, E. Monographie de reference, Millet raconté par lui-même – 3 volumes – Paris 1921

- Murphy, Alexandra R. Jean-François Millet. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1984. ISBN 0-87846-237-6

- Plaideux, Hugues. "L'inventaire après décès et la déclaration de succession de Jean-François Millet", in Revue de la Manche, t. 53, fasc. 212, 2e trim. 2011, p. 2–38.

- Plaideux, Hugues. "Une enseigne de vétérinaire cherbourgeois peinte par Jean-François Millet en 1841", in Bulletin de la Société française d'histoire de la médecine et des sciences vétérinaires, n° 11, 2011, p. 61–75.

- Pollock, Griselda. Millet. London: Oresko, 1977. ISBN 0905368134.

- Stokes, Simon. Art and Copyright. Hart Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84113-225-X

- Tadie, Andrew. Poetry and Peace: The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet by David Middleton Archived 14 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Modern Age: A Quarterly Review. Summer/Fall 2009 (Vol. 51:3)

External links[edit]

- jeanmillet.org; 125 works by Jean-François Millet

- Jean-François Millet at Artcyclopedia

- Maura Coughlin's article on Millet's Norman milkmaids

- Influence on Van Gogh

- Influence on Dali – grieving parents or praying peasants in The Angelus?

- Gillet, Louis (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Dilke, Emilia Francis Strong (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). pp. 466–467.

- "Jean-François Millet", poem by Florence Earle Coates

- Cartwright, Julia, (1902) Jean François Millet: his life and letters London: Swan Sonnenschein and Co.

- Sensier, Alfred, (1881) Jean-Francois Millet – Peasant and Painter (transl. Helena de Kay) London: Macmillan and Co.