Gran Chaco: Difference between revisions

Ira Leviton (talk | contribs) m Fixed a typo found with Wikipedia:Typo_Team/moss. |

m En dash fix (via WP:JWB) |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 27 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Region of south-central Southern America}} |

|||

{{ |

{{About||the Bolivian province|Gran Chaco Province|the Argentine province|Chaco Province|the region of Paraguay|Chaco (Paraguay)}} |

||

{{Lead too short|date=May 2020}} |

{{Lead too short|date=May 2020}} |

||

| Line 8: | Line 9: | ||

|image_alt = |

|image_alt = |

||

|caption = Landscape in the Gran Chaco,<br> Chaco Boreal, Paraguay |

|caption = Landscape in the Gran Chaco,<br> Chaco Boreal, Paraguay |

||

|map = |

|map = Gran-Chaco.png |

||

|map_size = |

|map_size = |

||

|map_alt = |

|map_alt = |

||

| Line 18: | Line 19: | ||

|border3 = [[Bolivian Yungas]] |

|border3 = [[Bolivian Yungas]] |

||

|border4 = [[Chiquitano dry forests]] |

|border4 = [[Chiquitano dry forests]] |

||

|border5 = [[ |

|border5 = [[High Monte]] |

||

|border6 = [[ |

|border6 = [[Humid Chaco]] |

||

|border7 = [[Southern Andean Yungas]] |

|border7 = [[Pantanal]] |

||

|border8 = [[Southern Andean Yungas]] |

|||

|animals = |

|animals = |

||

|bird_species = |

|bird_species = |

||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

|country = [[Paraguay]] |

|country = [[Paraguay]] |

||

|country1 = [[Bolivia]] |

|country1 = [[Bolivia]] |

||

|country2 = [[Argentina]] |

|country2 = [[Argentina]] |

||

|country3 = [[Brazil]] |

|country3 = [[Brazil]] |

||

|elevation = |

|elevation = |

||

| Line 39: | Line 41: | ||

|habitat_loss = |

|habitat_loss = |

||

|habitat_loss_ref = |

|habitat_loss_ref = |

||

|protected = 176,715 km |

|protected = 176,715 km<sup>2</sup> (22 |

||

|protected_ref = )<ref name =Dinerstein>Eric Dinerstein, David Olson, et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 6, June 2017, Pages 534–545; Supplemental material 2 table S1b. |

|protected_ref = )<ref name =Dinerstein>Eric Dinerstein, David Olson, et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 6, June 2017, Pages 534–545; Supplemental material 2 table S1b. {{doi|10.1093/biosci/bix014}}</ref> |

||

|embedded = |

|embedded = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

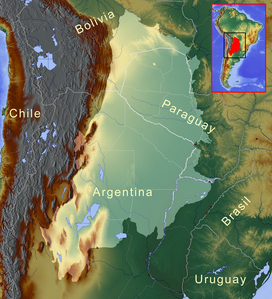

The '''Gran Chaco''' or '''Dry Chaco''' is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid [[lowland]] [[natural region]] of the [[Río de la Plata]] basin, divided among eastern [[Bolivia]], western [[Paraguay]], northern [[Argentina]], and a portion of the Brazilian states of [[Mato Grosso]] and [[Mato Grosso do Sul]], where it is connected with the [[Pantanal]] region. This land is sometimes called the '''Chaco Plain'''. |

The '''Gran Chaco''' or '''Dry Chaco''' is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid [[lowland]] [[tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests|tropical dry broadleaf forest]] [[natural region]] of the [[Río de la Plata]] basin, divided among eastern [[Bolivia]], western [[Paraguay]], northern [[Argentina]], and a portion of the Brazilian states of [[Mato Grosso]] and [[Mato Grosso do Sul]], where it is connected with the [[Pantanal]] region. This land is sometimes called the '''Chaco Plain'''. |

||

==Toponymy== |

==Toponymy== |

||

The name Chaco comes from a word in [[Quechuan languages|Quechua]], an indigenous language from the [[Andes]] and highlands of South America. The |

The name Chaco comes from a word in [[Quechuan languages|Quechua]], an indigenous language from the [[Andes]] and highlands of South America. The Quechua word ''chaqu'' meaning "hunting land" comes probably from the rich variety of animal life present throughout the entire region. |

||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

[[Image:Greenpeacehelicopter-Chaco.jpg|thumb|220px|left|A bulldozer clearing native forest in the Chaco Boreal and environmentalists campaigning against it]] [[Image:ParaguayChacoBorealdryseason.JPG|thumb|270px|Alto Chaco, virgin forest in dry season]] [[Image:Chaco Paraguay,cattle ranch, Presidente Hayes Province.JPG|thumb|270px|Bajo Chaco, extensive cattle ranching]][[Image:ParaguayChaco Clearings for cattle grazing.jpg|thumb|270px|Deforestation for cattle farming in the Paraguayan part of the Chaco]] {{Regions of Argentina}} |

[[Image:Greenpeacehelicopter-Chaco.jpg|thumb|220px|left|A bulldozer clearing native forest in the Chaco Boreal and environmentalists campaigning against it]] [[Image:ParaguayChacoBorealdryseason.JPG|thumb|270px|Alto Chaco, virgin forest in dry season]] [[Image:Chaco Paraguay,cattle ranch, Presidente Hayes Province.JPG|thumb|270px|Bajo Chaco, extensive cattle ranching]][[Image:ParaguayChaco Clearings for cattle grazing.jpg|thumb|270px|Deforestation for cattle farming in the Paraguayan part of the Chaco]] {{Regions of Argentina}} |

||

The Gran Chaco is about 647,500 km |

The Gran Chaco is about 647,500 km<sup>2</sup> (250,000 sq mi) in size, though estimates differ. It is located west of the [[Paraguay River]] and east of the [[Andes]], and is mostly an alluvial sedimentary plain shared among Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. It stretches from about [[17th parallel south|17]] to [[33rd parallel south|33°S]] latitude and between [[65th meridian west|65]] and [[60th meridian west|60°W]] longitude, though estimates differ. |

||

Historically, the Chaco has been divided in three main parts: the ''Chaco Austral'' or Southern Chaco, south of the [[Bermejo River]] and inside Argentinian territory, blending into the [[Pampa]] region in its southernmost end; the ''Chaco Central'' or Central Chaco between the Bermejo and the [[Pilcomayo River]] to the north, also now in Argentinian territory; and the ''Chaco Boreal'' or Northern Chaco, north of the Pilcomayo up to the Brazilian Pantanal, inside Paraguayan territory and sharing some area with Bolivia. |

Historically, the Chaco has been divided in three main parts: the ''Chaco Austral'' or Southern Chaco, south of the [[Bermejo River]] and inside Argentinian territory, blending into the [[Pampa]] region in its southernmost end; the ''Chaco Central'' or Central Chaco between the Bermejo and the [[Pilcomayo River]] to the north, also now in Argentinian territory; and the ''Chaco Boreal'' or Northern Chaco, north of the Pilcomayo up to the Brazilian Pantanal, inside Paraguayan territory and sharing some area with Bolivia. |

||

| Line 57: | Line 59: | ||

Locals sometimes divide it today by the political borders, giving rise to the terms Argentinian Chaco, Paraguayan Chaco, and Bolivian Chaco. (Inside Paraguay, people sometimes use the expression Central Chaco for the area roughly in the middle of the Chaco Boreal, where [[Mennonite]] colonies are established.) |

Locals sometimes divide it today by the political borders, giving rise to the terms Argentinian Chaco, Paraguayan Chaco, and Bolivian Chaco. (Inside Paraguay, people sometimes use the expression Central Chaco for the area roughly in the middle of the Chaco Boreal, where [[Mennonite]] colonies are established.) |

||

The Chaco Boreal may be divided in two: closer to the mountains in the west, the ''Alto Chaco'' (Upper Chaco), sometimes known as ''Chaco Seco'' (or Dry Chaco), is very dry and sparsely vegetated. To the east, less arid conditions combined with favorable soil characteristics permit a seasonally dry higher-growth thorn tree forest, and further east still higher rainfall combined with improperly drained lowland soils result in a somewhat swampy plain called the ''Bajo Chaco'' (Lower Chaco), sometimes known as ''Chaco Húmedo'' (Humid Chaco). It has a more open [[savanna]] vegetation consisting of palm trees, [[Schinopsis lorentzii|quebracho trees]], and tropical high-grass areas, with a wealth of [[insect]]s. The landscape is mostly flat and slopes at a 0.004-degree gradient to the east. This area is also one of the distinct [[physiographic]] provinces of the Parana-Paraguay Plain division. |

The Chaco Boreal may be divided in two: closer to the mountains in the west, the ''Alto Chaco'' (Upper Chaco), sometimes known as ''Chaco Seco'' (or Dry Chaco), is very dry and sparsely vegetated. To the east, less arid conditions combined with favorable soil characteristics permit a seasonally dry higher-growth thorn tree forest, and further east still higher rainfall combined with improperly drained lowland soils result in a somewhat swampy plain called the ''Bajo Chaco'' (Lower Chaco), sometimes known as ''Chaco Húmedo'' ([[Humid Chaco]]). It has a more open [[savanna]] vegetation consisting of palm trees, [[Schinopsis lorentzii|quebracho trees]], and tropical high-grass areas, with a wealth of [[insect]]s. The landscape is mostly flat and slopes at a 0.004-degree gradient to the east. This area is also one of the distinct [[physiographic]] provinces of the Parana-Paraguay Plain division. |

||

The areas more hospitable to development are along the [[Paraguay River|Paraguay]], [[Bermejo River|Bermejo]], and [[Pilcomayo River]]s. It is a great source of [[timber]] and [[tannin]], which is derived from the native ''quebracho'' tree. Special tannin factories have been constructed there. The wood of the [[Bulnesia sarmientoi|palo santo]] from the Central Chaco is the source of [[oil of guaiac]] (a fragrance for [[soap]]). Paraguay also cultivates [[yerba mate|mate]] in the lower part of the Chaco. |

The areas more hospitable to development are along the [[Paraguay River|Paraguay]], [[Bermejo River|Bermejo]], and [[Pilcomayo River]]s. It is a great source of [[timber]] and [[tannin]], which is derived from the native ''quebracho'' tree. Special tannin factories have been constructed there. The wood of the [[Bulnesia sarmientoi|palo santo]] from the Central Chaco is the source of [[oil of guaiac]] (a fragrance for [[soap]]). Paraguay also cultivates [[yerba mate|mate]] in the lower part of the Chaco. |

||

Large tracts of the central and northern Chaco have high [[Fertility (soil)|soil fertility]], sandy alluvial soils with elevated levels of [[phosphorus]],<ref>{{cite news |title=A postcard from the central Chaco |author=Don Nicol | |

Large tracts of the central and northern Chaco have high [[Fertility (soil)|soil fertility]], sandy alluvial soils with elevated levels of [[phosphorus]],<ref>{{cite news |title=A postcard from the central Chaco |author=Don Nicol |access-date=2009-01-23 |url=http://www.breedleader.com.au/images/chaco%20postcard%20.pdf |quote=alluvial sandy soils have P (phosphorus) levels of up to 200–300 ppm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090226104329/http://www.breedleader.com.au/images/chaco%20postcard%20.pdf |archive-date=2009-02-26}}</ref> and a topography that is favorable for agricultural development. Other aspects are challenging for farming: a semiarid to semihumid climate (600–1300 mm annual rainfall) with a six-month dry season and sufficient fresh groundwater restricted to roughly one-third of the region, two-thirds being without groundwater or with groundwater of high salinity. Soils are generally erosion-prone once the forest has been cleared. In the central and northern Paraguay Chaco, occasional dust storms have caused major topsoil loss. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The Chaco was occupied by nomadic peoples, notably the various groups making up the [[Guaycuru peoples|Guaycuru]], who resisted Spanish control, often with success, |

The Chaco was occupied by nomadic peoples, notably the various groups making up the [[Guaycuru peoples|Guaycuru]], who resisted Spanish control of the Chaco, often with success, from the 16th until the early 20th centuries. |

||

Prior to national independence of the nations that compose the Chaco, the entire area was a separate colonial region named by the Spaniards as ''Chiquitos''. |

Prior to national independence of the nations that compose the Chaco, the entire area was a separate colonial region named by the Spaniards as ''Chiquitos''. |

||

| Line 70: | Line 72: | ||

The Gran Chaco had been a disputed territory since 1810. Officially, it was supposed to be part of Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, although a bigger land portion west of the Paraguay River had belonged to Paraguay since its independence. Argentina claimed territories north of the Bermejo River until Paraguay's defeat in the [[War of the Triple Alliance]] in 1870 established its current border with Argentina. |

The Gran Chaco had been a disputed territory since 1810. Officially, it was supposed to be part of Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, although a bigger land portion west of the Paraguay River had belonged to Paraguay since its independence. Argentina claimed territories north of the Bermejo River until Paraguay's defeat in the [[War of the Triple Alliance]] in 1870 established its current border with Argentina. |

||

Over the next few decades, Bolivia began to push the natives out and settle in the Gran Chaco, while Paraguay ignored it. Bolivia sought the Paraguay River for shipping oil out into the sea (it had become a land-locked country after the loss of its Pacific coast in the [[War of the Pacific]]), and Paraguay claimed ownership of the land. This became the backdrop to [[the Gran Chaco War]] (1932–1935) between Paraguay and Bolivia over supposed oil in the Chaco Boreal (the aforementioned region north of the Pilcomayo River and to the west of the Paraguay River). Eventually, Argentine Foreign Minister [[Carlos Saavedra Lamas]] mediated a ceasefire and subsequent treaty signed in 1938, which gave Paraguay three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal and gave Bolivia a corridor to the Paraguay River with the ability to use the Puerto Casado and the right to construct their own port. No oil was found in the region until the |

Over the next few decades, Bolivia began to push the natives out and settle in the Gran Chaco, while Paraguay ignored it. Bolivia sought the Paraguay River for shipping oil out into the sea (it had become a land-locked country after the loss of its Pacific coast in the [[War of the Pacific]]), and Paraguay claimed ownership of the land. This became the backdrop to [[the Gran Chaco War]] (1932–1935) between Paraguay and Bolivia over supposed oil in the Chaco Boreal (the aforementioned region north of the Pilcomayo River and to the west of the Paraguay River). Eventually, Argentine Foreign Minister [[Carlos Saavedra Lamas]] mediated a ceasefire and subsequent treaty signed in 1938, which gave Paraguay three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal and gave Bolivia a corridor to the Paraguay River with the ability to use the Puerto Casado and the right to construct their own port. No oil was found in the region until 2012 when Paraguayan President [[Federico Franco]] announced the discovery of oil in the area of the Pirity river.<ref>[http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1530473-paraguay-encontro-petroleo-cerca-de-la-frontera-con-la-argentina "Paraguay encontró petróleo cerca de la frontera con la Argentina"] [[La Nación]], 26 November 2012 {{in lang|es}}</ref> |

||

[[Image:Aerial view of Km 75 Ruins.jpg|thumb|left|220px|Road construction in the deep Gran Chaco during the 1960s]] |

[[Image:Aerial view of Km 75 Ruins.jpg|thumb|left|220px|Road construction in the deep Gran Chaco during the 1960s]] |

||

| Line 83: | Line 85: | ||

It has high [[biodiversity]], containing around 3,400 plant species, 500 birds, 150 mammals, and 220 reptiles and amphibians.<ref name="WWF">{{cite web |title=The Gran Chaco |website=WWF |url=http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/agriculture/soy/soyreport/soy_and_deforestation/the_gran_chaco/ |access-date=2017-07-06 |quote=The Gran Chaco was one of the last frontiers in South America – but agricultural development, largely driven by soy, is gathering pace.}}</ref> |

It has high [[biodiversity]], containing around 3,400 plant species, 500 birds, 150 mammals, and 220 reptiles and amphibians.<ref name="WWF">{{cite web |title=The Gran Chaco |website=WWF |url=http://wwf.panda.org/what_we_do/footprint/agriculture/soy/soyreport/soy_and_deforestation/the_gran_chaco/ |access-date=2017-07-06 |quote=The Gran Chaco was one of the last frontiers in South America – but agricultural development, largely driven by soy, is gathering pace.}}</ref> |

||

The floral characteristics of the Gran Chaco are varied given the large geographical span of the region. The dominant vegetative structure is xerophytic deciduous forests with multiple layers, including a [[canopy (trees)]], subcanopy, [[shrub layer]], and [[herbaceous layer]]. Ecosystems include [[riverine forest]]s, [[wetlands]], [[savannas]], and cactus stands, as well.<ref name="Prado">What is Gran Chaco vegetation in South America? I. A review. Contribution to the study of flora and vegetation of Chaco. V. Candollea, 48: |

The floral characteristics of the Gran Chaco are varied given the large geographical span of the region. The dominant vegetative structure is xerophytic deciduous forests with multiple layers, including a [[canopy (trees)]], subcanopy, [[shrub layer]], and [[herbaceous layer]]. Ecosystems include [[riverine forest]]s, [[wetlands]], [[savannas]], and cactus stands, as well.<ref name="Prado">What is Gran Chaco vegetation in South America? I. A review. Contribution to the study of flora and vegetation of Chaco. V. Candollea, 48: 145–172, 1993.</ref> |

||

At higher elevations of the eastern zone of the [[Humid Chaco]], mature forests transition from the wet forests of southern Brazil. These woodlands are dominated by canopy trees such as ''[[Handroanthus impetiginosus]]'' and characterized by frequent [[lianas]] and [[epiphytes]]. This declines to seasonally flooded forests, at lower elevations, that are dominated by ''[[Schinopsis]]'' spp., a common plains tree genus often harvested for its [[tannin]] content and dense wood. The understory comprises bromeliad and cactus species, as well as hardy shrubs such as ''[[Schinus |

At higher elevations of the eastern zone of the [[Humid Chaco]], mature forests transition from the wet forests of southern Brazil. These woodlands are dominated by canopy trees such as ''[[Handroanthus impetiginosus]]'' and characterized by frequent [[lianas]] and [[epiphytes]]. This declines to seasonally flooded forests, at lower elevations, that are dominated by ''[[Schinopsis]]'' spp., a common plains tree genus often harvested for its [[tannin]] content and dense wood. The understory comprises bromeliad and cactus species, as well as hardy shrubs such as ''[[Schinus fasciculata]]''. These lower areas lack lianas, but have abundant epiphytic species such as ''[[Tillandsia]]''. The river systems that flow through the area, such as the [[Rio Paraguay]] and [[Rio Parana]], allow for seasonally flooded semievergreen [[gallery forests]] that hold riparian species such as ''[[Tessaria integrifolia]]'' and ''[[Salix humboldtiana]]''. Other seasonally flooded ecosystems of this area include palm-dominated (''[[Copernicia alba]]'') savannas with a [[bunch grass]]-dominated herbaceous layer. |

||

To the west, in the Semiarid/Arid Chaco, |

To the west, in the Semiarid/Arid Chaco, medium-sized forests consists of white quebracho (''[[Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco]]'') and red quebracho (''[[Schinopsis lorentzii]]'') with a slightly shorter subcanopy made up of several species from the family Fabaceae, as well as several arboreal cacti species that distinguish this area of the Chaco. There is a scrub-like shrub and herbaceous understory. On sandy soils, the thick woodlands turn into savannas where the aforementioned species prevail, as well as species such as ''[[Jacaranda mimosifolia]]''. The giant ''[[Stetsonia coryne]]'', found throughout the western Semiarid/Arid region becomes very conspicuous in these sandy savannas. Various upland systems of plant associations occur throughout the Gran Chaco. The Highlands of the Argentinian Chaco are made up of, on the dry, sunny side (up to 1800m), ''[[Schinopsis haenkeana]]'' woodlands. The cooler side of the uplands hosts ''[[Zanthoxylum coco]]'' (locally referred to as [[Fagara coco]]) and ''[[Schinus molleoides]]'' (locally referred to as ''[[Lithrea molleoides]]'') as the predominant species. Other notable species include ''[[Bougainvillea stipitata]]'', and several species from the Fabaceae. The Paraguayan uplands have other woodland slope ecosystems, notably, those dominated by ''[[Anadenanthera colubrina]]'' on moist slopes.<ref name="Prado" /> Both of these upland systems, as well as numerous other Gran Chaco areas, are rich with [[endemism]]. |

||

==Fauna== |

==Fauna== |

||

Faunal diversity in the Gran Chaco is also high. The Gran Chaco has around 3,400 plant, 500 bird, 150 mammal, and 220 reptile and amphibian species. Animals typically associated with tropical and subtropical forests are often found throughout the eastern Humid Chaco, including jaguars, howler monkeys, peccaries, deer, and tapirs. ''[[Edentate]]'' species, including anteaters and armadillos, are readily seen here, as well.<ref name="Fernandez-Duque">Napamalo: The Giant Anteater of the Gran Chaco, 2003.</ref> Being home to at least 10 species, the Argentinian Chaco is the location of the peak diversity for the armadillo, including species such as the [[nine-banded armadillo]] (''Dasypus novemcinctus''), whose range extends north to the southern US, and the [[southern three-banded armadillo]] (''Tolypeutes matacus'').<ref name="Bolkovic and Zuleta">Conservation ecology of armadillos in the Chaco region of Argentina, 1: 16-17, Edentata, 1994.</ref> The [[pink fairy armadillo]] (''Chlamyphrous truncatus''), is found nowhere else in the world.<ref name="Lucero and Olrog">Guiá de los Mamiferos Argentinos, 19840.</ref> The [[giant armadillo]] (''Priodontes maximus''), while not found in the eastern Humid Chaco, can be seen in the drier Arid Chaco of the west. Some other notable endemics of the region include the [[San Luis tuco-tuco]] (''Ctenomys pontifex'').<ref name="Fernandez-Duque" /> This small rodent is only found in the Argentinian Chaco. All of 60 species of ''[[Ctenomys]]'' are endemic to South America. The [[Chacoan peccary]] (''Catagonus wagneri''), locally known as ''tauga'', is the largest of the three peccary species found in the area. This species was thought to be extinct by scientists until 1975, when it was recorded by |

Faunal diversity in the Gran Chaco is also high. The Gran Chaco has around 3,400 plant, 500 bird, 150 mammal, and 220 reptile and amphibian species. Animals typically associated with tropical and subtropical forests are often found throughout the eastern Humid Chaco, including jaguars, howler monkeys, peccaries, deer, and tapirs. ''[[Edentate]]'' species, including anteaters and armadillos, are readily seen here, as well.<ref name="Fernandez-Duque">Napamalo: The Giant Anteater of the Gran Chaco, 2003.</ref> Being home to at least 10 species, the Argentinian Chaco is the location of the peak diversity for the armadillo, including species such as the [[nine-banded armadillo]] (''Dasypus novemcinctus''), whose range extends north to the southern US, and the [[southern three-banded armadillo]] (''Tolypeutes matacus'').<ref name="Bolkovic and Zuleta">Conservation ecology of armadillos in the Chaco region of Argentina, 1: 16-17, Edentata, 1994.</ref> The [[pink fairy armadillo]] (''Chlamyphrous truncatus''), is found nowhere else in the world.<ref name="Lucero and Olrog">Guiá de los Mamiferos Argentinos, 19840.</ref> The [[giant armadillo]] (''Priodontes maximus''), while not found in the eastern Humid Chaco, can be seen in the drier Arid Chaco of the west. Some other notable endemics of the region include the [[San Luis tuco-tuco]] (''Ctenomys pontifex'').<ref name="Fernandez-Duque" /> This small rodent is only found in the Argentinian Chaco. All of 60 species of ''[[Ctenomys]]'' are endemic to South America. The [[Chacoan peccary]] (''Catagonus wagneri''), locally known as ''tauga'', is the largest of the three peccary species found in the area. This species was thought to be extinct by scientists until 1975, when it was recorded by Ralph Wetzel.<ref name="Wetzel, Dubos, Martin, and Myers">Catagonous, an "extinct" peccary, alive in Paraguay, 189:379-381, Science, 1975. {{doi|10.1126/science.189.4200.379}}</ref> |

||

Due to the climate of the Gran Chaco, [[herpetofauna]] are restricted to moist [[Refugium (population biology)|refugia]] in various places throughout the chaco. Rotting logs, debris piles, old housing settlement, wells, and seasonal farm ponds are examples of such refugia.<ref name="Talbot"> |

Due to the climate of the Gran Chaco, [[herpetofauna]] are restricted to moist [[Refugium (population biology)|refugia]] in various places throughout the chaco. Rotting logs, debris piles, old housing settlement, wells, and seasonal farm ponds are examples of such refugia.<ref name="Talbot">Ecological Notes on the Paraguayan Chaco Herpetofauna, 12(3), 433-435, Journal of Herpetology, 1978. {{JSTOR|1563636}}</ref> The [[black-legged seriema]] (''Chunga burmeisteri''), [[blue-crowned parakeet]] (''Aratinga acuticadauta''), [[Picui ground dove]] (''Columbina picui''), [[guira cuckoo]] (''Guira guira''), [[little thornbird]] (''Phacellodomus sibilatrix''), and [[many-colored Chaco finch]] (''Saltaitricula multicolor'') are notable of the 409 bird species that are resident or breed in the Gran Chaco; 252 of these Chaco species are endemic to South America.<ref name="Short">"A Zoogeographic Analysis Of The South American Chaco Avifauna", 154(3), 165–352, ''Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History'', 1975. {{hdl|2246/608}}</ref> |

||

==Conservation issues== |

==Conservation issues== |

||

[[File:Sorghum linea 14 Alto Paraguay.jpg|thumb|220px|Sorghum harvest 2008, Linea 14, Agua Dulce Region, [[Alto Paraguay]]]] |

[[File:Sorghum linea 14 Alto Paraguay.jpg|thumb|220px|Sorghum harvest 2008, Linea 14, Agua Dulce Region, [[Alto Paraguay]]]] |

||

The Chaco is one of South America's last agricultural frontiers. Very sparsely populated and lacking sufficient all-weather roads and basic infrastructure (the Argentinian part is more developed than the Paraguayan or Bolivian part), it has long been too remote for crop planting. The central Chaco's [[Mennonites in Paraguay|Mennonite colonies]] are a notable exception. |

The Chaco is one of South America's last agricultural frontiers. Very sparsely populated and lacking sufficient all-weather roads and basic infrastructure (the Argentinian part is more developed than the Paraguayan or Bolivian part), it has long been too remote for crop planting. The central Chaco's [[Mennonites in Paraguay|Mennonite colonies]] are a notable exception. Between 2000 and 2019, it was estimated that the Dry Chaco forest cover decreased by 20.2%, including territory in Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, with the latter showing the most dramatic land cover change.<ref>de la Sancha, Noé U., Sarah A. Boyle, Nancy E. McIntyre, Daniel M. Brooks, Alberto Yanosky, Ericka Cuellar Soto, Fatima Mereles, Micaela Camino, and Richard D. Stevens. "The disappearing Dry Chaco, one of the last dry forest systems on earth." Landscape Ecology 36 (2021): 2997-3012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01291-x</ref> |

||

Two factors may substantially change the Chaco in the near future: low land valuations<ref>{{cite news |title=Impenetrable olvido (..tan bajo el valor de la tierra que con dos campañas, sobra..) |language= |

Two factors may substantially change the Chaco in the near future: low land valuations<ref>{{cite news |title=Impenetrable olvido (..tan bajo el valor de la tierra que con dos campañas, sobra..) |language=es |publisher=AMBIENTE-ARGENTINA |url=http://ipsnoticias.net/nota.asp?idnews=87208 |access-date=2008-09-09 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120709193832/http://ipsnoticias.net/nota.asp?idnews=87208 |archive-date=2012-07-09}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Cada vez más Uruguayos compran campos Guaranés |language=es |publisher=Consejo de Educacion Secundaria de Uruguay |date=26 June 2008 |url=http://www.ces.edu.uy/Relaciones_Publicas/BoletinPrensa/2007-08/20070824.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090225075115/http://www.ces.edu.uy/Relaciones_Publicas/BoletinPrensa/2007-08/20070824.pdf |archive-date=25 February 2009}}</ref> and the region's suitability to grow [[Energy crop|fuel crops]]. Suitability for the cultivation of ''[[Jatropha]]'' has been proven.<ref>{{cite news |title=Jatropha en el Chaco |language=es |publisher=Diario ABC Digital |url=http://www.abc.com.py/suplementos/rural/articulos.php?pid=424986 |access-date=2008-09-09}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Jatropha Chaco |language=es |publisher=Incorporación del cultivo Jatropha Curcas L en zonas marginales de la provincia de chaco |url=http://www.jatrophachaco.com/portal/index |access-date=2008-09-09 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081011025424/http://www.jatrophachaco.com/portal/index |archive-date=2008-10-11}}</ref> [[Sweet sorghum]] as an ethanol plant may prove viable, too, since sorghum is a traditional local crop for domestic and feedstock use. The feasibility of [[switchgrass]] is currently being studied by Argentina's [[Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria]],<ref>{{cite news |title=Aprovechamiento de recursos vegetales y animales para la produccion de biocombustibles |language=es |publisher=INTA |date=26 June 2008 |url=http://www.inta.gov.ar/iir/investiga/proyectos/pebiocombustibles.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20100926025739/http%3A//www.inta.gov.ar/iir/investiga/proyectos/pebiocombustibles.pdf |archive-date=26 September 2010}}</ref> as is the [[Copernicia alba|Karanda’y palm tree]] in the Paraguayan Chaco.<ref>{{cite news |title=Varias iniciativas están en marcha con vistas a la producción de biodiesel |language=es |publisher=RIEDEX / Ministerio de Industria y Comercio (de Paraguay) |url=http://www.rediex.gov.py/index.php?Itemid=293&id=259&option=com_content&task=view |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090308032645/http://www.rediex.gov.py/index.php?Itemid=293&id=259&option=com_content&task=view |url-status=dead |archive-date=2009-03-08 |access-date=2008-09-09}}</ref> |

||

While advancements in agriculture can bring some improvements in infrastructure and employment for the region, [[loss of habitat]] and virgin forest is substantial and will likely increase [[poverty]]. Paraguay, after having lost more than 90% of its Atlantic rainforest between 1975 and 2005, is now losing its [[xerophyte|xerophytic forest]] (dry forests) in the Chaco at an annual rate of {{convert|220,000|ha}} (2008).<ref>{{cite news |title=Deforestation in Paraguay: Over 1500 football pitches lost a day in the Chaco |publisher=World Land Trust |date=30 November 2009 |url=http://www.worldlandtrust.org/news/2009/11/deforestation-in-paraguay-over-1500.htm |access-date=14 January 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100823025904/http://www.worldlandtrust.org/news/2009/11/deforestation-in-paraguay-over-1500.htm |archive-date=23 August 2010 |url-status=dead}}</ref> In mid-2009, a projected law, initiated by the [[Authentic Radical Liberal Party|Liberal Party]], that would have outlawed [[deforestation]] in the Paraguayan Chaco altogether, "Deforestacion Zero en el Chaco" did not get a majority in the parliament. |

While advancements in agriculture can bring some improvements in infrastructure and employment for the region, [[loss of habitat]] and virgin forest is substantial and will likely increase [[poverty]]. Paraguay, after having lost more than 90% of its Atlantic rainforest between 1975 and 2005, is now losing its [[xerophyte|xerophytic forest]] (dry forests) in the Chaco at an annual rate of {{convert|220,000|ha}} (2008).<ref>{{cite news |title=Deforestation in Paraguay: Over 1500 football pitches lost a day in the Chaco |publisher=World Land Trust |date=30 November 2009 |url=http://www.worldlandtrust.org/news/2009/11/deforestation-in-paraguay-over-1500.htm |access-date=14 January 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100823025904/http://www.worldlandtrust.org/news/2009/11/deforestation-in-paraguay-over-1500.htm |archive-date=23 August 2010 |url-status=dead}}</ref> In mid-2009, a projected law, initiated by the [[Authentic Radical Liberal Party|Liberal Party]], that would have outlawed [[deforestation]] in the Paraguayan Chaco altogether, "Deforestacion Zero en el Chaco" did not get a majority in the parliament. |

||

Deforestation in the Argentinian part of the Chaco amounted to an average of {{convert|100,000|ha}} per year between 2001 and 2007.<ref>{{cite news |title=Deforestation and fragmentation of Chaco dry forest in NW Argentina (1972–2007) |first=Ignacio Gasparri |last=H. Ricardo Grau |date=27 June 2008 |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T6X-4VYMP1Y-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1166267745&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3b7d9911ef8ae04e96e043393eac2966 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130201195518/http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T6X-4VYMP1Y-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1166267745&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3b7d9911ef8ae04e96e043393eac2966 |url-status=dead |archive-date=1 February 2013}}</ref> According to [[Fundación Avina]], a local NGO, on average, {{convert|1130|ha|acre|abbr=on}} are cleared per day. The [[soy]] plantations not only eliminate the forest, but also other types of agriculture. Indigenous communities are losing their land to agribusinesses. Since 2007, a law is supposed to regulate and control the cutting of timber in the Gran Chaco, but [[illegal logging]] continues.<ref>http://www.dandc.eu/en/article/logging-subtropical-dry-forest-deprives-indigenous-people-argentina-their-livelihood</ref> |

Deforestation in the Argentinian part of the Chaco amounted to an average of {{convert|100,000|ha}} per year between 2001 and 2007.<ref>{{cite news |title=Deforestation and fragmentation of Chaco dry forest in NW Argentina (1972–2007) |first=Ignacio Gasparri |last=H. Ricardo Grau |date=27 June 2008 |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T6X-4VYMP1Y-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1166267745&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3b7d9911ef8ae04e96e043393eac2966 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130201195518/http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T6X-4VYMP1Y-1&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_searchStrId=1166267745&_rerunOrigin=google&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3b7d9911ef8ae04e96e043393eac2966 |url-status=dead |archive-date=1 February 2013}}</ref> According to [[Fundación Avina]], a local NGO, on average, {{convert|1130|ha|acre|abbr=on}} are cleared per day. The [[soy]] plantations not only eliminate the forest, but also other types of agriculture. Indigenous communities are losing their land to agribusinesses. Since 2007, a law is supposed to regulate and control the cutting of timber in the Gran Chaco, but [[illegal logging]] continues.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dandc.eu/en/article/logging-subtropical-dry-forest-deprives-indigenous-people-argentina-their-livelihood |title=Conquest by chainsaw |date=24 September 2013 |first=Julio César |last=Bernio |website=www.dandc.eu}}</ref> |

||

Among the aggressive investors in the Paraguayan Gran Chaco are U.S.-based agribusinesses [[Cargill Inc.]], [[Bunge Ltd.]], and [[Archer Daniels Midland]] Co.<ref name="MacDonald 2014">{{cite |

Among the aggressive investors in the Paraguayan Gran Chaco are U.S.-based agribusinesses [[Cargill Inc.]], [[Bunge Ltd.]], and [[Archer Daniels Midland]] Co.<ref name="MacDonald 2014">{{cite magazine |last=MacDonald |first=Christine |title=The Tragic Deforestation of the Chaco |magazine=Rolling Stone |date=2014-07-28 |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/green-going-gone-the-tragic-deforestation-of-the-chaco-20140728 |access-date=2017-07-06}}</ref> |

||

==Protected areas== |

==Protected areas== |

||

A 2017 assessment found that 176,715 |

A 2017 assessment found that 176,715 km<sup>2</sup>, or 22%, of the ecoregion is in protected areas.<ref name =Dinerstein/> |

||

In September 1995, the [[Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area]] was established in an area of the Chaco in Bolivia. It is administered and was established solely by the [[indigenous peoples]], including the [[Guarani people|Izoceño Guaraní]], the [[Ayoreode]], and the [[Chiquitano]]. |

In September 1995, the [[Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area]] was established in an area of the Chaco in Bolivia. It is administered and was established solely by the [[indigenous peoples]], including the [[Guarani people|Izoceño Guaraní]], the [[Ayoreode]], and the [[Chiquitano]]. |

||

| Line 113: | Line 115: | ||

Other protected areas include [[Defensores del Chaco National Park]] and [[Tinfunqué National Park]] in Paraguay, and [[Copo National Park]] and [[El Impenetrable National Park]] in Argentina. |

Other protected areas include [[Defensores del Chaco National Park]] and [[Tinfunqué National Park]] in Paraguay, and [[Copo National Park]] and [[El Impenetrable National Park]] in Argentina. |

||

{{ |

{{See also|National Parks in the Chaco, Paraguay}} |

||

==Administrative divisions in the Gran Chaco== |

==Administrative divisions in the Gran Chaco== |

||

| Line 149: | Line 151: | ||

| [[Tarija Department]] |

| [[Tarija Department]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Alto Paraguay Department]] |

| [[Alto Paraguay Department]] || rowspan="3" | Paraguay |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Boquerón Department]] |

| [[Boquerón Department]] |

||

| Line 193: | Line 195: | ||

* [[Sanapaná]]<ref name=the/> (Quiativis), Paraguay |

* [[Sanapaná]]<ref name=the/> (Quiativis), Paraguay |

||

* [[Vilela people|Vilela]], Argentina |

* [[Vilela people|Vilela]], Argentina |

||

* [[Wichí people|Wichí]] ( |

* [[Wichí people|Wichí]] (Mataco),<ref name=the/> Argentina and Bolivia |

||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

Many of these peoples speak or used to speak [[Mataco–Guaicuru languages]].<ref name="Campbell-Chaco">{{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Lyle | |

Many of these peoples speak or used to speak [[Mataco–Guaicuru languages]].<ref name="Campbell-Chaco">{{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Lyle |author-link=Lyle Campbell |last2=Grondona |first2=Verónica |editor1-last=Grondona |editor1-first=Verónica |editor2-last=Campbell |editor2-first=Lyle |date=2012 |title=The Indigenous Languages of South America |chapter=Languages of the Chaco and Southern Cone |series=The World of Linguistics |volume=2 |location=Berlin |publisher=De Gruyter Mouton |pages=625–668 |isbn=9783110255133}}</ref> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 204: | Line 206: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

* Gordillo, Gastón. "Places and academic disputes: the Argentine Gran Chaco." in ''A Companion to Latin American Anthropology'' (2008): 447–465. [https://www.academia.edu/download/56353946/deborah_poole_antropologia.pdf#page=457 online] |

|||

* Hirsch, Silvia et al. eds. ''Reimagining the Gran Chaco: Identities, Politics, and the Environment in South America'' (University Press of Florida, 2021) [https://www.amazon.com/Reimagining-Gran-Chaco-Identities-Environment/dp/1683402111/ excerpt] also see [http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=57435 online review] |

|||

* Krebs, Edgardo, and José Braunstein. "The renewal of Gran Chaco studies." ''History of Anthropology Newsletter'' 28.1 (2011): 9–19. [https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1824&context=han online] |

|||

* Le Polain de Waroux, Yann, et al. "Rents, actors, and the expansion of commodity frontiers in the Gran Chaco." ''Annals of the American Association of Geographers'' 108.1 (2018): 204–225. [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/24694452.2017.1360761 online] |

|||

* Mendoza, Marcela. "The Bolivian Toba (Guaicuruan) Expansion in Northern Gran Chaco, 1550–1850." ''Ethnohistory'' 66.2 (2019): 275–300. [https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marcela-Mendoza-6/publication/332128566_The_Bolivian_Toba_Guaicuruan_Expansion_in_Northern_Gran_Chaco_1550-1850/links/5ca28d9f92851cf0aea79e05/The-Bolivian-Toba-Guaicuruan-Expansion-in-Northern-Gran-Chaco-1550-1850.pdf online] |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{ |

{{Commons category|Gran Chaco|<br>Gran Chaco}} |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20041010034925/http://www.nmnh.si.edu/botany/projects/cpd/sa/sa22.htm The National Museum of Natural History's description of Gran Chaco] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20041010034925/http://www.nmnh.si.edu/botany/projects/cpd/sa/sa22.htm The National Museum of Natural History's description of Gran Chaco] |

||

* {{WWF ecoregion|id=nt0210|name=Chaco}} |

* {{WWF ecoregion|id=nt0210|name=Chaco}} |

||

| Line 213: | Line 222: | ||

{{coord|19.1622|S|61.4702|W|source:kolossus-huwiki|display=title}} |

{{coord|19.1622|S|61.4702|W|source:kolossus-huwiki|display=title}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Gran Chaco| ]] |

[[Category:Gran Chaco| ]] |

||

| Line 235: | Line 245: | ||

[[Category:Geography of Mato Grosso do Sul]] |

[[Category:Geography of Mato Grosso do Sul]] |

||

[[Category:Geography of Paraguay]] |

[[Category:Geography of Paraguay]] |

||

[[Category:Divided regions]] |

|||

[[Category:Environment of Mato Grosso]] |

[[Category:Environment of Mato Grosso]] |

||

[[Category:Environment of Mato Grosso do Sul]] |

[[Category:Environment of Mato Grosso do Sul]] |

||

| Line 241: | Line 250: | ||

[[Category:Physiographic provinces]] |

[[Category:Physiographic provinces]] |

||

[[Category:Neotropical dry broadleaf forests]] |

[[Category:Neotropical dry broadleaf forests]] |

||

[[Category:Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 11:22, 3 May 2024

| Gran Chaco Dry Chaco | |

|---|---|

Landscape in the Gran Chaco, Chaco Boreal, Paraguay | |

Dry Chaco as delimited by the World Wildlife Fund | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Neotropical |

| Biome | tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 786,791 km2 (303,782 sq mi) |

| Countries | |

| Conservation | |

| Protected | 176,715 km2 (22%)[1] |

The Gran Chaco or Dry Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semiarid lowland tropical dry broadleaf forest natural region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay, northern Argentina, and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, where it is connected with the Pantanal region. This land is sometimes called the Chaco Plain.

Toponymy[edit]

The name Chaco comes from a word in Quechua, an indigenous language from the Andes and highlands of South America. The Quechua word chaqu meaning "hunting land" comes probably from the rich variety of animal life present throughout the entire region.

Geography[edit]

| Regions of Argentina |

|---|

The Gran Chaco is about 647,500 km2 (250,000 sq mi) in size, though estimates differ. It is located west of the Paraguay River and east of the Andes, and is mostly an alluvial sedimentary plain shared among Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. It stretches from about 17 to 33°S latitude and between 65 and 60°W longitude, though estimates differ.

Historically, the Chaco has been divided in three main parts: the Chaco Austral or Southern Chaco, south of the Bermejo River and inside Argentinian territory, blending into the Pampa region in its southernmost end; the Chaco Central or Central Chaco between the Bermejo and the Pilcomayo River to the north, also now in Argentinian territory; and the Chaco Boreal or Northern Chaco, north of the Pilcomayo up to the Brazilian Pantanal, inside Paraguayan territory and sharing some area with Bolivia.

Locals sometimes divide it today by the political borders, giving rise to the terms Argentinian Chaco, Paraguayan Chaco, and Bolivian Chaco. (Inside Paraguay, people sometimes use the expression Central Chaco for the area roughly in the middle of the Chaco Boreal, where Mennonite colonies are established.)

The Chaco Boreal may be divided in two: closer to the mountains in the west, the Alto Chaco (Upper Chaco), sometimes known as Chaco Seco (or Dry Chaco), is very dry and sparsely vegetated. To the east, less arid conditions combined with favorable soil characteristics permit a seasonally dry higher-growth thorn tree forest, and further east still higher rainfall combined with improperly drained lowland soils result in a somewhat swampy plain called the Bajo Chaco (Lower Chaco), sometimes known as Chaco Húmedo (Humid Chaco). It has a more open savanna vegetation consisting of palm trees, quebracho trees, and tropical high-grass areas, with a wealth of insects. The landscape is mostly flat and slopes at a 0.004-degree gradient to the east. This area is also one of the distinct physiographic provinces of the Parana-Paraguay Plain division.

The areas more hospitable to development are along the Paraguay, Bermejo, and Pilcomayo Rivers. It is a great source of timber and tannin, which is derived from the native quebracho tree. Special tannin factories have been constructed there. The wood of the palo santo from the Central Chaco is the source of oil of guaiac (a fragrance for soap). Paraguay also cultivates mate in the lower part of the Chaco.

Large tracts of the central and northern Chaco have high soil fertility, sandy alluvial soils with elevated levels of phosphorus,[2] and a topography that is favorable for agricultural development. Other aspects are challenging for farming: a semiarid to semihumid climate (600–1300 mm annual rainfall) with a six-month dry season and sufficient fresh groundwater restricted to roughly one-third of the region, two-thirds being without groundwater or with groundwater of high salinity. Soils are generally erosion-prone once the forest has been cleared. In the central and northern Paraguay Chaco, occasional dust storms have caused major topsoil loss.

History[edit]

The Chaco was occupied by nomadic peoples, notably the various groups making up the Guaycuru, who resisted Spanish control of the Chaco, often with success, from the 16th until the early 20th centuries.

Prior to national independence of the nations that compose the Chaco, the entire area was a separate colonial region named by the Spaniards as Chiquitos.

The Gran Chaco had been a disputed territory since 1810. Officially, it was supposed to be part of Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, although a bigger land portion west of the Paraguay River had belonged to Paraguay since its independence. Argentina claimed territories north of the Bermejo River until Paraguay's defeat in the War of the Triple Alliance in 1870 established its current border with Argentina.

Over the next few decades, Bolivia began to push the natives out and settle in the Gran Chaco, while Paraguay ignored it. Bolivia sought the Paraguay River for shipping oil out into the sea (it had become a land-locked country after the loss of its Pacific coast in the War of the Pacific), and Paraguay claimed ownership of the land. This became the backdrop to the Gran Chaco War (1932–1935) between Paraguay and Bolivia over supposed oil in the Chaco Boreal (the aforementioned region north of the Pilcomayo River and to the west of the Paraguay River). Eventually, Argentine Foreign Minister Carlos Saavedra Lamas mediated a ceasefire and subsequent treaty signed in 1938, which gave Paraguay three-quarters of the Chaco Boreal and gave Bolivia a corridor to the Paraguay River with the ability to use the Puerto Casado and the right to construct their own port. No oil was found in the region until 2012 when Paraguayan President Federico Franco announced the discovery of oil in the area of the Pirity river.[3]

Mennonites immigrated into the Paraguayan part of the region from Canada in the 1920s; more came from the USSR in the 1930s and immediately following World War II. These immigrants created some of the largest and most prosperous municipalities in the deep Gran Chaco.

The region is home to over 9 million people, divided about evenly among Argentina, Bolivia, and Brazil, and including around 100,000 in Paraguay. The area remains relatively underdeveloped, In the 1960s, the Paraguayan authorities constructed the Trans-Chaco Highway and the Argentine National Highway Directorate, National Routes 16 and 81, in an effort to encourage access and development. All three highways extend about 700 km (430 mi) from east to west and are now completely paved, as is a network of nine Brazilian highways in Mato Grosso do Sul state.

Flora[edit]

The Gran Chaco has some of the highest temperatures on the continent.

It has high biodiversity, containing around 3,400 plant species, 500 birds, 150 mammals, and 220 reptiles and amphibians.[4]

The floral characteristics of the Gran Chaco are varied given the large geographical span of the region. The dominant vegetative structure is xerophytic deciduous forests with multiple layers, including a canopy (trees), subcanopy, shrub layer, and herbaceous layer. Ecosystems include riverine forests, wetlands, savannas, and cactus stands, as well.[5]

At higher elevations of the eastern zone of the Humid Chaco, mature forests transition from the wet forests of southern Brazil. These woodlands are dominated by canopy trees such as Handroanthus impetiginosus and characterized by frequent lianas and epiphytes. This declines to seasonally flooded forests, at lower elevations, that are dominated by Schinopsis spp., a common plains tree genus often harvested for its tannin content and dense wood. The understory comprises bromeliad and cactus species, as well as hardy shrubs such as Schinus fasciculata. These lower areas lack lianas, but have abundant epiphytic species such as Tillandsia. The river systems that flow through the area, such as the Rio Paraguay and Rio Parana, allow for seasonally flooded semievergreen gallery forests that hold riparian species such as Tessaria integrifolia and Salix humboldtiana. Other seasonally flooded ecosystems of this area include palm-dominated (Copernicia alba) savannas with a bunch grass-dominated herbaceous layer.

To the west, in the Semiarid/Arid Chaco, medium-sized forests consists of white quebracho (Aspidosperma quebracho-blanco) and red quebracho (Schinopsis lorentzii) with a slightly shorter subcanopy made up of several species from the family Fabaceae, as well as several arboreal cacti species that distinguish this area of the Chaco. There is a scrub-like shrub and herbaceous understory. On sandy soils, the thick woodlands turn into savannas where the aforementioned species prevail, as well as species such as Jacaranda mimosifolia. The giant Stetsonia coryne, found throughout the western Semiarid/Arid region becomes very conspicuous in these sandy savannas. Various upland systems of plant associations occur throughout the Gran Chaco. The Highlands of the Argentinian Chaco are made up of, on the dry, sunny side (up to 1800m), Schinopsis haenkeana woodlands. The cooler side of the uplands hosts Zanthoxylum coco (locally referred to as Fagara coco) and Schinus molleoides (locally referred to as Lithrea molleoides) as the predominant species. Other notable species include Bougainvillea stipitata, and several species from the Fabaceae. The Paraguayan uplands have other woodland slope ecosystems, notably, those dominated by Anadenanthera colubrina on moist slopes.[5] Both of these upland systems, as well as numerous other Gran Chaco areas, are rich with endemism.

Fauna[edit]

Faunal diversity in the Gran Chaco is also high. The Gran Chaco has around 3,400 plant, 500 bird, 150 mammal, and 220 reptile and amphibian species. Animals typically associated with tropical and subtropical forests are often found throughout the eastern Humid Chaco, including jaguars, howler monkeys, peccaries, deer, and tapirs. Edentate species, including anteaters and armadillos, are readily seen here, as well.[6] Being home to at least 10 species, the Argentinian Chaco is the location of the peak diversity for the armadillo, including species such as the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), whose range extends north to the southern US, and the southern three-banded armadillo (Tolypeutes matacus).[7] The pink fairy armadillo (Chlamyphrous truncatus), is found nowhere else in the world.[8] The giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), while not found in the eastern Humid Chaco, can be seen in the drier Arid Chaco of the west. Some other notable endemics of the region include the San Luis tuco-tuco (Ctenomys pontifex).[6] This small rodent is only found in the Argentinian Chaco. All of 60 species of Ctenomys are endemic to South America. The Chacoan peccary (Catagonus wagneri), locally known as tauga, is the largest of the three peccary species found in the area. This species was thought to be extinct by scientists until 1975, when it was recorded by Ralph Wetzel.[9]

Due to the climate of the Gran Chaco, herpetofauna are restricted to moist refugia in various places throughout the chaco. Rotting logs, debris piles, old housing settlement, wells, and seasonal farm ponds are examples of such refugia.[10] The black-legged seriema (Chunga burmeisteri), blue-crowned parakeet (Aratinga acuticadauta), Picui ground dove (Columbina picui), guira cuckoo (Guira guira), little thornbird (Phacellodomus sibilatrix), and many-colored Chaco finch (Saltaitricula multicolor) are notable of the 409 bird species that are resident or breed in the Gran Chaco; 252 of these Chaco species are endemic to South America.[11]

Conservation issues[edit]

The Chaco is one of South America's last agricultural frontiers. Very sparsely populated and lacking sufficient all-weather roads and basic infrastructure (the Argentinian part is more developed than the Paraguayan or Bolivian part), it has long been too remote for crop planting. The central Chaco's Mennonite colonies are a notable exception. Between 2000 and 2019, it was estimated that the Dry Chaco forest cover decreased by 20.2%, including territory in Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay, with the latter showing the most dramatic land cover change.[12]

Two factors may substantially change the Chaco in the near future: low land valuations[13][14] and the region's suitability to grow fuel crops. Suitability for the cultivation of Jatropha has been proven.[15][16] Sweet sorghum as an ethanol plant may prove viable, too, since sorghum is a traditional local crop for domestic and feedstock use. The feasibility of switchgrass is currently being studied by Argentina's Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria,[17] as is the Karanda’y palm tree in the Paraguayan Chaco.[18]

While advancements in agriculture can bring some improvements in infrastructure and employment for the region, loss of habitat and virgin forest is substantial and will likely increase poverty. Paraguay, after having lost more than 90% of its Atlantic rainforest between 1975 and 2005, is now losing its xerophytic forest (dry forests) in the Chaco at an annual rate of 220,000 hectares (540,000 acres) (2008).[19] In mid-2009, a projected law, initiated by the Liberal Party, that would have outlawed deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco altogether, "Deforestacion Zero en el Chaco" did not get a majority in the parliament.

Deforestation in the Argentinian part of the Chaco amounted to an average of 100,000 hectares (250,000 acres) per year between 2001 and 2007.[20] According to Fundación Avina, a local NGO, on average, 1,130 ha (2,800 acres) are cleared per day. The soy plantations not only eliminate the forest, but also other types of agriculture. Indigenous communities are losing their land to agribusinesses. Since 2007, a law is supposed to regulate and control the cutting of timber in the Gran Chaco, but illegal logging continues.[21]

Among the aggressive investors in the Paraguayan Gran Chaco are U.S.-based agribusinesses Cargill Inc., Bunge Ltd., and Archer Daniels Midland Co.[22]

Protected areas[edit]

A 2017 assessment found that 176,715 km2, or 22%, of the ecoregion is in protected areas.[1]

In September 1995, the Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area was established in an area of the Chaco in Bolivia. It is administered and was established solely by the indigenous peoples, including the Izoceño Guaraní, the Ayoreode, and the Chiquitano.

Other protected areas include Defensores del Chaco National Park and Tinfunqué National Park in Paraguay, and Copo National Park and El Impenetrable National Park in Argentina.

Administrative divisions in the Gran Chaco[edit]

The following Argentine provinces, Bolivian and Paraguayan departments, and Brazilian states lie in the Gran Chaco area, either entirely or in part.

Indigenous peoples[edit]

- Abipón, Argentina, historic group

- Angaite (Angate), northwestern Paraguay

- Ayoreo[23] (Morotoco, Moro, Zamuco), Bolivia and Paraguay

- Chamacoco (Zamuko),[23] Paraguay

- Chané, Argentina and Bolivia

- Chiquitano (Chiquito, Tarapecosi), eastern Bolivia

- Chorote (Choroti),[23] Iyojwa'ja Chorote, Manjuy), Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay

- Guana[23] (Kaskihá), Paraguay

- Guaraní,[23] Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay

- Bolivian Guarani

- Eastern Guarani (Chiriguano), Bolivia

- Guarayo (East Bolivian Guarani)

- Chiripá (Tsiripá, Ava), Bolivia

- Pai Tavytera (Pai, Montese, Ava), Bolivia

- Tapieté (Guaraní Ñandéva, Yanaigua),[23] eastern Bolivia

- Yuqui (Bia), Bolivia

- Bolivian Guarani

- Guaycuru peoples, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay

- Kaiwá,[23] Argentina and Brazil

- Lengua people (Enxet),[23] Paraguay

- North Lengua (Eenthlit, Enlhet, Maskoy), Paraguay

- South Lengua, Paraguay

- Lulé (Pelé, Tonocoté), Argentina

- Maká[23] (Towolhi), Paraguay

- Nivaclé (Ashlushlay,[23] Chulupí, Chulupe, Guentusé), Argentina, and Paraguay

- Sanapaná[23] (Quiativis), Paraguay

- Vilela, Argentina

- Wichí (Mataco),[23] Argentina and Bolivia

Many of these peoples speak or used to speak Mataco–Guaicuru languages.[24]

See also[edit]

- Campo del Cielo

- Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area

- Tributaries of the Río de la Plata

References[edit]

- ^ a b Eric Dinerstein, David Olson, et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 6, June 2017, Pages 534–545; Supplemental material 2 table S1b. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014

- ^ Don Nicol. "A postcard from the central Chaco" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2009-01-23.

alluvial sandy soils have P (phosphorus) levels of up to 200–300 ppm

- ^ "Paraguay encontró petróleo cerca de la frontera con la Argentina" La Nación, 26 November 2012 (in Spanish)

- ^ "The Gran Chaco". WWF. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

The Gran Chaco was one of the last frontiers in South America – but agricultural development, largely driven by soy, is gathering pace.

- ^ a b What is Gran Chaco vegetation in South America? I. A review. Contribution to the study of flora and vegetation of Chaco. V. Candollea, 48: 145–172, 1993.

- ^ a b Napamalo: The Giant Anteater of the Gran Chaco, 2003.

- ^ Conservation ecology of armadillos in the Chaco region of Argentina, 1: 16-17, Edentata, 1994.

- ^ Guiá de los Mamiferos Argentinos, 19840.

- ^ Catagonous, an "extinct" peccary, alive in Paraguay, 189:379-381, Science, 1975. doi:10.1126/science.189.4200.379

- ^ Ecological Notes on the Paraguayan Chaco Herpetofauna, 12(3), 433-435, Journal of Herpetology, 1978. JSTOR 1563636

- ^ "A Zoogeographic Analysis Of The South American Chaco Avifauna", 154(3), 165–352, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, 1975. hdl:2246/608

- ^ de la Sancha, Noé U., Sarah A. Boyle, Nancy E. McIntyre, Daniel M. Brooks, Alberto Yanosky, Ericka Cuellar Soto, Fatima Mereles, Micaela Camino, and Richard D. Stevens. "The disappearing Dry Chaco, one of the last dry forest systems on earth." Landscape Ecology 36 (2021): 2997-3012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-021-01291-x

- ^ "Impenetrable olvido (..tan bajo el valor de la tierra que con dos campañas, sobra..)" (in Spanish). AMBIENTE-ARGENTINA. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "Cada vez más Uruguayos compran campos Guaranés" (PDF) (in Spanish). Consejo de Educacion Secundaria de Uruguay. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009.

- ^ "Jatropha en el Chaco" (in Spanish). Diario ABC Digital. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "Jatropha Chaco" (in Spanish). Incorporación del cultivo Jatropha Curcas L en zonas marginales de la provincia de chaco. Archived from the original on 2008-10-11. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "Aprovechamiento de recursos vegetales y animales para la produccion de biocombustibles" (PDF) (in Spanish). INTA. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2010.

- ^ "Varias iniciativas están en marcha con vistas a la producción de biodiesel" (in Spanish). RIEDEX / Ministerio de Industria y Comercio (de Paraguay). Archived from the original on 2009-03-08. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- ^ "Deforestation in Paraguay: Over 1500 football pitches lost a day in the Chaco". World Land Trust. 30 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- ^ H. Ricardo Grau, Ignacio Gasparri (27 June 2008). "Deforestation and fragmentation of Chaco dry forest in NW Argentina (1972–2007)". Archived from the original on 1 February 2013.

- ^ Bernio, Julio César (24 September 2013). "Conquest by chainsaw". www.dandc.eu.

- ^ MacDonald, Christine (2014-07-28). "The Tragic Deforestation of the Chaco". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2017-07-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Cultural Thesaurus." Archived 2011-04-29 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the American Indian. (retrieved 18 Feb 2011)

- ^ Campbell, Lyle; Grondona, Verónica (2012). "Languages of the Chaco and Southern Cone". In Grondona, Verónica; Campbell, Lyle (eds.). The Indigenous Languages of South America. The World of Linguistics. Vol. 2. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 625–668. ISBN 9783110255133.

Further reading[edit]

- Gordillo, Gastón. "Places and academic disputes: the Argentine Gran Chaco." in A Companion to Latin American Anthropology (2008): 447–465. online

- Hirsch, Silvia et al. eds. Reimagining the Gran Chaco: Identities, Politics, and the Environment in South America (University Press of Florida, 2021) excerpt also see online review

- Krebs, Edgardo, and José Braunstein. "The renewal of Gran Chaco studies." History of Anthropology Newsletter 28.1 (2011): 9–19. online

- Le Polain de Waroux, Yann, et al. "Rents, actors, and the expansion of commodity frontiers in the Gran Chaco." Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108.1 (2018): 204–225. online

- Mendoza, Marcela. "The Bolivian Toba (Guaicuruan) Expansion in Northern Gran Chaco, 1550–1850." Ethnohistory 66.2 (2019): 275–300. online

External links[edit]

Gran Chaco.

- The National Museum of Natural History's description of Gran Chaco

- "Chaco". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- photos of the Paraguay Chaco

- Gran Chaco

- La Plata basin

- Natural regions of South America

- Regions of Argentina

- Regions of Bolivia

- Regions of Paraguay

- Ecoregions of South America

- Ecoregions of Argentina

- Ecoregions of Bolivia

- Ecoregions of Brazil

- Ecoregions of Paraguay

- Grasslands of Argentina

- Grasslands of Bolivia

- Grasslands of Brazil

- Grasslands of Paraguay

- Grasslands of South America

- Geography of Argentina

- Geography of Bolivia

- Geography of Mato Grosso

- Geography of Mato Grosso do Sul

- Geography of Paraguay

- Environment of Mato Grosso

- Environment of Mato Grosso do Sul

- Quechua words and phrases

- Physiographic provinces

- Neotropical dry broadleaf forests

- Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests