Bighorn sheep

| Bighorn Sheep | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | O. canadensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ovis canadensis Shaw, 1804

| |

Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis)[1] is one of three species of mountain sheep in North America and Siberia; the other two species being Ovis dalli, that includes Dall Sheep and Stone's Sheep, and the Siberian Snow sheep Ovis nivicola. The taxononomy continues to be modified as new genetic and morphologic data becomes available but most scientists currently recognize the following subspecies of bighorn:[2][3]

- Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis)

- Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae), formerly California Bighorn Sheep, [3]* Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni) Bighorn Sheep can see thier enemy about a mile or so away.

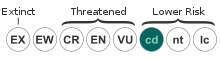

In addition, there are currently two federally endangered populations:[4]

- Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis sierrae), recognized as a unique subspecies

- Peninsular Bighorn Sheep, a distinct population segment of Desert Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni)

Origin

Wild sheep crossed the Bering land bridge from Siberia during the Pleistocene (~750,000 years ago) and, subsequently, spread through western North America as far south as Baja California and northern mainland Mexico.[5] Divergence from their closest Asian ancestor (Snow sheep) occurred about 600,000 years ago[6]. In North America, wild sheep have diverged into two extant species -- Dall sheep that occupy Alaska and northwestern Canada, and bighorn sheep that range from southern Canada to Mexico. However, the status of these species is questionable given that hybridization has occurred between them in their recent evolutionary history.[7]

History

Two hundred years ago, Bighorn Sheep were widespread throughout the western United States, Canada, and Northern Mexico. Some estimates placed their population at higher than 2 million. However, by around 1900, hunting, competition from domesticated sheep, and diseases had decreased the population to only several thousand. A program of reintroductions, natural parks, and reduced hunting, together with a decrease in domesticated sheep near the end of World War 2, allowed the Bighorn Sheep to make a comeback, though not before O. c. auduboni, a sub-species that lived on the Black Hills, went extinct.

Mythology

Bighorn sheep were amongst the most admired animals of the Apsaalooka, or Crow, people, and what is today called the Bighorn Mountain Range was central to the Apsaalooka tribal lands. In the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area book, storyteller Old Coyote describes a legend related to the bighorn sheep. A man possessed by evil spirits attempts to kill his heir by pushing the young man over a cliff, but the victim is saved by getting caught in trees. Rescued by bighorn sheep, the man takes the name of their leader, Big Metal. The other sheep grant him power, wisdom, sharp eyes, sure footedness, keen ears, great strength and a strong heart. Big Metal returns to his people with the message that the Apsaalooka people will survive only so long as the river winding out of the mountains is known as the Bighorn River.[8]

Economic Importance

Bighorn Sheep are hunted for their meat and horns, which are used in ceremonies, as food, and as hunting trophies. They also serve as a source of eco-tourism, as tourists come to see the famed Bighorn Sheep in their native habitat. [citation needed]

Characteristics

Bighorn Sheep are named for the large, curved horns borne by the males, or rams. Females, or ewes, also have horns, but they are short with only a slight curvature. They range in color from light brown to grayish or dark, chocolate brown, with a white rump and lining on the back of all four legs. Rocky Mountains bighorn females weigh up to 200 pounds (90 kg), and males occasionally exceed 300 pounds (135 kg). In contrast, Sierra Nevada bighorn females weigh about 140 pounds (63 kg) with males weighing around 200 pounds (90 kg). Males' horns can weigh up to 30 lbs (14 kg), as much as the rest of the bones in the male's body.[9]

Bighorn sheep graze on grasses and browse shrubs, particularly in fall and winter, and seek minerals at natural salt licks. Bighorns are well adapted to climbing steep terrain where they seek cover from predators such as coyotes, eagles, and cougars. They live in large herds, but because they do not have the strict dominance hierarchy of the mouflon, they cannot be domesticated. This is because bighorns do not automatically follow a single leader ram as the Asiatic ancestors of the domestic sheep did and do.

Prior to the mating season or "rut", the rams attempt to establish a dominance hierarchy that determines access to ewes for mating. It is during the prerut period that most of the characteristic horn clashing occurs between rams, although this behavior may occur to a limited extent throughout the year.[10] Ram's horns can frequently exhibit damage from repeated clashes. Bighorn ewes exhibit a six-month gestation. In temperate climates, the peak of the rut occurs in November with one, or rarely two, lambs being born in May. The lambs are then weaned for 4-6 months.

Bighorn sheep are highly susceptible to certain diseases carried by domestic sheep such as scabies and pneumonia; additional mortality occurs as a result of accidents involving rock fall or falling off cliffs (a hazard of living in steep, rugged terrain).

Scientific analysis

Bighorn Sheep are considered good indicators of land health because the species is sensitive to many human-induced environmental problems. In addition to their aesthetic value, Bighorn Sheep are considered desirable game animals by hunters. The Rocky Mountain and Sierra Nevada bighorn occupy the cooler mountainous regions of Canada and the United States. In contrast, the Desert Bighorn Sheep subspecies are indigenous to the hot desert ecosystems of the Southwest United States.

In 1940, Cowan taxonomically split the species into seven subspecies:[5]

- Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis canadensis. Habitat: from British Columbia to Arizona.

- California Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis californiana. Owens defined the habitat from British Columbia down to California and over to North Dakota. The definition of this subspecies has been updated (see below).

- Nelson's Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis nelsoni, the most common desert bighorn sheep, ranges from California through Arizona.

- Mexicana Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis mexicana, range from Arizona and New Mexico down to Sonora and Chihuahua.

- Peninsular Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis cremnobates. Habitat: the Peninsular Ranges of California and Baja California.

- Weems' Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis weemsi. Habitat: Baja California.

- Audubon's Bighorn Sheep Ovis canadensis auduboni. Habitat: North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska. Extinct since 1925.

However, starting in 1993, Ramey and colleagues,[6][11] using DNA testing, have shown that this division into seven subspecies is largely illusory. The latest science shows that Bighorn Sheep is one species, with 3 subspecies O. c. canadensis, O. c. nelsoni and O. c. sierrae. O. c. sierrae is a genetically distinct subspecies that only occurs in the Sierra Nevada. O. c. nelsoni occur throughout the southwestern desert regions of the U.S. and Mexico, whereas O. c. canadensis occupy the U.S. and Canadian Rocky Mountains and the northwestern U.S.

Bighorn Sheep in culture

The Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep is the provincial mammal of Alberta and the state animal of Colorado and as such is incorporated into the symbol for the Colorado Department of Wildlife [12].

Bighorn sheep were once known by the scientific identification argali or argalia due to assumption that they were the same animal as the Asiatic Argali (Ovis ammon).[13] Lewis and Clark recorded numerous sightings of Ovis canadensis in the journals of their exploration--sometimes using the name Argalia. In addition, they recorded the use of bighorn sheep by the Shoshone in making bows.[14] William Clark's Track Map produced after the expedition in 1814 indicates a tributary of the Yellowstone River named Argalia Creek and a tributary of the Missouri River named Argalia River, both in what is today Montana. Neither of these tributaries retained these names however. The Bighorn River another tributary of the Yellowstone, and its tributary stream the Little Bighorn River indicated on Clark's map did retain their names, the latter being the namesake of the Battle of the Little Bighorn.[15]

References

- ^ "Ovis canadensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. 18 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ Wehausen, J.D. (2000). "Cranial morphometric and evolutionary relationships in the northern range of Ovis canadensis". J. Mammology. 81: 145–161.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wehausen, J. D. (2005). "Correct nomenclature for Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep". California Fish and Game. 91: 216–218.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ a b Cowan, I. McT (1940). "Distribution and variation in the native sheep of North America". American Midland Naturalist. 24: 505–580.

- ^ a b Ramey, R. R. II (1993). "Evolutionary genetics and systematics of North American mountain sheep". Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Loehr, J. (2006). "Evidence for cryptic glacial refugia from North American mountain sheep mitochondrial DNA". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 19: 419–430.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Graetz, Rick. "Introduction to the Crow". Little Big Horn College Library. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ovis canadensis". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

- ^ Valdez, R. (1999). Mountain Sheep of North America. The University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wehausen, J. D. (1993). "A morphometric reevaluation of the Peninsular bighorn subpecies". Trans. Desert Bighorn Council. 37: 1–10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ [1] retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ^ Stewart, George R., Jr. (December 1935). "Popular Names of the Mountain Sheep". American Speech. 10 (4). Duke University Press: 283–288. doi:10.2307/451603.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tubbs, Stephenie Ambrose (2003). The Lewis and Clark Companion: An Encyclopedia Guide to the Voyage of Discovery. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 12–13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|isnn=ignored (help) - ^ Lewis, Samuel (1814). "A Map of Lewis and Clark's track across the western portion of North America, from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean". Longman, Hurst, Reese, Orme and Brown. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Other sources

- Description of Bighorn Sheep at Yellowstone Park (public domain source)

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service draft recovery plan for the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep (public domain source)