Vedas

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

- "Veda" redirects here. For other uses, see Veda (disambiguation).

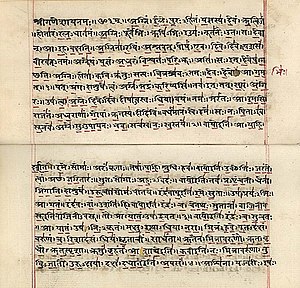

The Vedas (Sanskrit véda वेद "knowledge") are a large corpus of texts originating in Ancient India. They form the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature[1] and the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism.[2]

According to Hindu tradition, the Vedas are apauruṣeya "not human compositions"[3], being supposed to have been directly revealed, and thus are called śruti ("what is heard").[4][5] Vedic mantras are recited at Hindu prayers, religious functions and other auspicious occasions.

Philosophies and sects that developed in the Indian subcontinent have taken differing positions on the Vedas. Schools of Indian philosophy which cite the Vedas as their scriptural authority are classified as "orthodox" (āstika). Other traditions, notably Buddhism and Jainism, though they are (like the vedanta) similarly concerned with liberation did not regard the Vedas as divine ordinances but rather human expositions of the sphere of higher spiritual knowledge, hence not sacrosanct. These groups are referred to as "heterodox" or "non-orthodox" (nāstika) schools.[6] In addition to Buddhism and Jainism, Sikhism also does not accept the authority of the Vedas.[7] [8]

Etymology and usage

The Sanskrit word véda "knowledge, wisdom" is derived from the root vid- "to know". This is reconstructed as being derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *u̯eid-, meaning "see" or "know".[9]

As a noun, the word appears only in a single instance in the Rigveda, in RV 8.19.5, translated by Griffith as "ritual lore":

- yáḥ samídhā yá âhutī / yó védena dadâśa márto agnáye / yó námasā svadhvaráḥ

- "The mortal who hath ministered to Agni with oblation, fuel, ritual lore, and reverence, skilled in sacrifice."

The noun is from PIE *u̯eidos, cognate to Greek (ϝ)εἶδος "aspect, form". Not to be confused is the homonymous 1st and 3rd person singular perfect tense véda, cognate to Greek (ϝ)οἶδα (w)oida "I know". Root cognate are Greek ἰδέα, English wit, witness, German wissen (to know, knowledge), Swedish veta (to know), Latin video (I see), Czech vím (I know) or vidím (I see), Dutch weten (to know).[10]

In its narrowest sense, the term Veda is used to refer to the Samhitas (collection of mantras, or chants) associated with the four canonical Vedas (Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda and Atharvaveda) though typically the reference also includes the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and Upanishads attached to the Samhitas. In post-Vedic speculation, the term was further extended to refer to Itihasas (epics) and Puranas, each of which is sometimes designated as the "fifth Veda"; and in its widest interpretation, Veda can subsume "potentially all brahmanical texts, teachings and practices."[11] In its primary meaning, as a common noun meaning "knowledge"", veda can also be used to refer to fields of study unrelated to liturgy or ritual, freely compounded e.g. in agada-veda "medical science", sasya-veda "science of agriculture" or sarpa-veda "science of snakes"; durveda means "without knowledge, ignorant".

Dating

The Vedas are arguably the oldest sacred texts that are still used. Most Indologists agree that an oral tradition existed long before a literary tradition gradually sets in from about the 2nd century BCE.[12] Due to the ephemeral nature of the manuscript material (birch bark or palm leaves), surviving manuscripts rarely surpass an age of a few hundred years. The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Rigveda are dated to the 11th century CE.

The Vedic period lasts for at least a millennium, spanning the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age. Gavin Flood[13] sums up mainstream estimates, according to which the Rigveda was compiled from as early as 1500 BCE over a period of several centuries. The Vedic period reaches its peak only after the composition of the mantra texts, with the establishment of the various shakhas all over Northern India which annotated the mantra samhitas with Brahmana commentaries, and reaches its end in the age of Buddha and Panini and the rise of the Mahajanapadas (archaeologically, Northern Black Polished Ware). Michael Witzel gives a time span of c. 1500 BCE to c. 500-400 BCE. Witzel makes special reference to the Mitanni material of ca. 1400 BCE as the only epigraphic record of Indo-Aryan that may date to the Rigvedic period, admitting this does still not allow for an absolute dating of any Vedic text. He gives 150 BCE (Patanjali) as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature, and 1200 BCE (the early Iron Age) as terminus post quem for the Atharvaveda.[14]

Categories of Vedic texts

Vedic texts are traditionally categorized into four classes: the Saṃhitās (mantras), Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads.[15][16] Also classified as "Vedic" is certain Sutra literature, i.e. the Shrautasutras and the Grhyasutras.

- The Samhita (Sanskrit saṃhitā, "collection"), are collections of metric texts ("mantras"). There are four "Vedic" Samhitas: the Rig-Veda, Sama-Veda, Yajur-Veda, and Atharva-Veda, most of which are available in several recensions (śākhā). In some contexts, the term Veda is used to refer to these Samhitas. This is the oldest layer of Vedic texts, apart from the Rigvedic hymns, which were probably essentially complete by 1200 BC, dating to ca. the 12th to 10th centuries BC. The complete corpus of Vedic mantras as collected in Bloomfield's Vedic Concordance (1907) consists of some 89,000 padas (metric feet), of which 72,000 occur in the four Samhitas.[17]

- The Brahmanas are prose texts that discuss, in technical fashion, the solemn sacrificial rituals as well as comment on their meaning and many connected themes. Each of the Brahmanas is associated with one of the Samhitas or its recensions. The Brahmanas may either form separate texts or can be partly integrated into the text of the Samhitas. They may also include the Aranyakas and Upanishads.

- The Aranyakas, or "wilderness texts", are the concluding part of the Brahmanas that contain discussions and interpretations of dangerous rituals (to be studied outside the settlement) and various sorts of additional materials.

- The Upanishads are largely philosophical works in dialog form. They discuss question of nature philosophy and the fate of the soul, and contain some mystic and spiritual interpretations of the Vedas. For long, they have been regarded as their putative end and essence, and are thus known as Vedānta ("the end of the Vedas"). Taken together, they are the basis of the Vedanta school.

This group of texts is called shruti (Sanskrit: śruti; "the heard"). Since post-Vedic times it has been considered to be revealed wisdom, as distinct from other texts, collectively known as smriti (Sanskrit: smṛti; "the remembered"), that is texts that are considered to be of human origin. This system of categorization was developed by Max Müller and, while it is subject to some debate, it is still widely used. As Axel Michaels explains:

These classifications are often not tenable for linguistic and formal reasons: There is not only one collection at any one time, but rather several handed down in separate Vedic schools; Upanişads ... are sometimes not to be distinguished from Āraṇyakas...; Brāhmaṇas contain older strata of language attributed to the Saṃhitās; there are various dialects and locally prominent traditions of the Vedic schools. Nevertheless, it is advisable to stick to the division adopted by Max Müller because it follows the Indian tradition, conveys the historical sequence fairly accurately, and underlies the current editions, translations, and monographs on Vedic literature."[18]

The Shrauta Sutras, regarded as belonging to the smriti, are late Vedic in language and content, thus forming part of the Vedic Sanskrit corpus.[19][20] The composition of the Shrauta and Grhya Sutras (ca. 6th century BC) marks the end of the Vedic period , and at the same time the beginning of the flourishing of the "circum-Vedic" scholarship of Vedanga, introducing the early flowering of classical Sanskrit literature in the Maurya period.

While production of Brahmanas and Aranyakas ceases with the end of the Vedic period, there is a large number of Upanishads composed after the end of the Vedic period. While most of the ten mukhya Upanishads can be considered to date to the Vedic or Mahajanapada period, most of the 108 Upanishads of the full Muktika canon date to the Common Era. The Brahmanas, Aranyakas, and Upanishads often interpret the polytheistic and ritualistic Samhitas in philosophical and metaphorical ways to explore abstract concepts such as the Absolute (Brahman), and the soul or the self (Atman), introducing Vedanta philosophy, the basis of later Hinduism.

Vedic schools or recensions

Study of the extensive body of Vedic texts has been organized into a number of different schools or branches (Sanskrit śākhā, literally "branch" or "limb") each of which specialized in learning certain texts.[21] Multiple recensions are known for each of the Vedas, and each Vedic text may have a number of schools associated with it. Elaborate methods for preserving the text were originally based on memorizing by heart instead of writing. Specific techniques for parsing and chanting the texts were used to assist in the memorization process. (See also: patha)

Exegetical literature developed in the Vedic schools but comparatively few early medieval commentaries have survived. Sayana, from the 14th century, is known for his elaborate commentaries on the Vedic texts. All classes (varna) in early Vedic society were allowed to study the Vedas and there were Vedic sages that authored the Vedas(Rishis)that were women. However, the later dharmashastras, from the Sutra age, dictate and women and Shudras were neither required nor allowed to study the Veda.[citation needed] These dharmashastras regard the study of the Vedas a religious duty of the three upper varnas (Brahmins, Kshatriyas and Vaishyas).[citation needed]

The Four Vedas

The canonical division of the Vedas is fourfold (turīya) viz.,[22]

- Rig-Veda (RV)

- Yajur-Veda (YV, with the main division TS vs. VS)

- Sama-Veda (SV)

- Atharva-Veda (AV)

Of these, the first three were the principal original division, also called trayī, "the triple Vidyā", that is, "the triple sacred science" of reciting hymns (RV), performing sacrifices (YV), and chanting (SV).[23][24] This triplicity is so introduced in the Brahmanas (ShB, ABr and others), but the Rigveda is the only original work of the three with the other two largely borrowing from it.

Thus, the Mantras are properly of three forms: 1. Ric, which are verses of praise in metre, and intended for loud recitation; 2. Yajus, which are in prose, and intended for recitation in a lower tone at sacrifices; 3. Sāman, which are in metre, and intended for chanting at the Soma ceremonies.

The Yajurveda and Samaveda are not so much independent collections of prayers and hymns as special prayer- and hymn-books intended as manuals for the Adhvaryu and Udgatr priests respectively.

Subsequently, the Atharvaveda was added as the fourth Veda. Its status was probably not completely accepted till after Manusmrti, which often speaks of the three Vedas, calling them trayam-brahma-sanātanam, "the triple eternal Veda". The Atharvaveda like the Rigveda, is a collection of original hymns mixed up with incantations, borrowing little from the Rig and having no direct relation to sacrifices, but supposed by mere recitation to produce long life, to cure diseases, or effect the ruin of enemies.

Each of the four Vedas consists of the metrical Mantra or Samhita and the prose Brahmana part, giving directions for the detail of the ceremonies at which the Mantras were to be used and explanations of the legends connected with the Mantras. Both these portions are termed shruti, heard but not composed or written down by men. Each of the four Vedas seems to have passed through numerous Shakhas or schools, giving rise to various recensions of the text. They each have an Index or Anukramani, the principal work of this kind being the general Index or Sarvānukramaṇī.

The Rig-Veda

The Rig-Veda Samhita is the oldest significant existent Indian text.[25] It is a collection of 1,028 Vedic Sanskrit hymns and 10,600 verses in all, organized into ten books (Sanskrit: mandalas).[26] The hymns are dedicated to Rigvedic deities.[27]

The books were composed by sages and poets from different priestly groups over a period of at least 500 years, which Avari dates as 1400 BCE to 900 BCE, if not earlier[28] According to Max Müller, based on internal evidence (philological and linguistic), the Rigveda was composed roughly between 1700–1100 BCE (the early Vedic period) in the Punjab (Sapta Sindhu) region of the Indian subcontinent.[29] Michael Witzel believes that the Rig Veda must have been composed more or less in the period 1450-1350 BCE.[30]

There are strong linguistic and cultural similarities between the Rigveda and the early Iranian Avesta, deriving from the Proto-Indo-Iranian times, often associated with the Andronovo culture; the earliest horse-drawn chariots were found at Andronovo sites in the Sintashta-Petrovka cultural area near the Ural mountains and date to ca. 2000 BCE.[31]

The Yajur-Veda

The Yajur-Veda ("Veda of sacrificial formulas") consists of archaic prose mantras and also in part of verses borrowed from the Rig-Veda. Its purpose was practical, in that each mantra must accompany an action in sacrifice but, unlike the Sama-Veda, it was compiled to apply to all sacrificial rites, not merely the Soma offering. There are two major recensions of this Veda known as the "Black" and "White" Yajur-Veda. The origin and meaning of these designations are not very clear. The White Yajur-Veda contains only the verses and sayings necessary for the sacrifice, while explanations exist in a separate Brahmana work. It differs widely from the Black Yajurveda, which incorporates such explanations in the work itself, often immediately following the verses. Of the Black Yajurveda four major recensions survive, all showing by and large the same arrangement, but differing in many other respects, notably in the individual discussion of the rituals but also in matters of phonology and accent.

The Sama-Veda

The Sama-Veda (Sanskrit sāmaveda ) is the "Veda of chants" or "Knowledge of melodies". The name of this Veda is from the Sanskrit word sāman which means a metrical hymn or song of praise.[32] It consists of 1549 stanzas, taken entirely (except 78) from the Rig-Veda.[33] Some of the Rig-Veda verses are repeated more than once. Including repetitions, there are a total of 1875 verses numbered in the Sama-Veda recension published by Griffith.[34] Two major recensions remain today, the Kauthuma/Ranayaniya and the Jaiminiya.

Its purpose was liturgical and practical, to serve as a songbook for the "singer" priests who took part in the liturgy. A priest who sings hymns from the Sama-Veda during a ritual is called an udgātṛ, a word derived from the Sanskrit root ud-gai ("to sing" or "to chant").[35] A similar word in English might be "cantor". The styles of chanting are important to the liturgical use of the verses. The hymns were to be sung according to certain fixed melodies; hence the name of the collection.

The Atharva-Veda

The Artharva-Veda is the "Knowledge of the [atharvans] (and Angirasa)". The Artharva-Veda or Atharvangirasa is the text 'belonging to the Atharvan and Angirasa' poets. Apte defines an atharvan as a priest who worshipped fire and Soma.[36] The etymology of Atharvan is unclear, but according to Mayrhofer it is related to Avesta athravan (āθrauuan); he denies any connection with fire priests.[37] Atharvan was an ancient term for a certain Rishi even in the Rigveda. (The older literature took them as priests who worshipped fire).

The Atharva-Veda Saṃhitā has 760 hymns, and about 160 of the hymns are in common with the Rig-Veda.[38] Most of the verses are metrical, but some sections are in prose.[39]

It was compiled around 900 BCE, although some of its material may go back to the time of the Rig Veda,[40] and some parts of the Atharva-Veda are older than the Rig-Veda.[41]

The Atharvana-Veda is preserved in two recensions, the Paippalāda and Śaunaka.[42] According to Apte it had nine schools (shakhas).[43] The Paippalada version is longer than the Saunaka one; it is only partially printed and remains untranslated.

Unlike the other three Vedas, the Atharvana-Veda has less connection with sacrifice.[44][45] Its first part consists chiefly of spells and incantations, concerned with protection against demons and disaster, spells for the healing of diseases, and for long life.[46][47]

The second part of the text contains speculative and philosophical hymns. R. C. Zaehner notes that:

"The latest of the four Vedas, the Atharva-Veda, is, as we have seen, largely composed of magical texts and charms, but here and there we find cosmological hymns which anticipate the Upanishads, -- hymns to Skambha, the 'Support', who is seen as the first principle which is both the material and efficient cause of the universe, to Prāna, the 'Breath of Life', to Vāc, the 'Word', and so on.[48]

In its third section, the Atharvaveda contains Mantras used in marriage and death rituals, as well as those for kingship, female rivals and the Vratya (in Brahmana style prose).

Gavin Flood discusses the relatively late acceptance of the Atharva-Veda as follows:

"There were originally only three priests associated with the first three Saṃhitās, for the Brahman as overseer of the rites does not appear in the Ṛg Veda and is only incorporated later, thereby showing the acceptance of the Atharva Veda, which had been somewhat distinct from the other Saṃhitās and identified with the lower social strata, as being of equal standing with the other texts."[49]

Brahmanas

The mystical notions surrounding the concept of "Veda" that would flower in Vedantic philosophy have their roots already in Brahmana literature, notably in the Shatapatha Brahmana. The Vedas are identified with Brahman, the universal principle (ŚBM 10.1.1.8, 10.2.4.6). Vāc "speech" is called the "mother of the Vedas" (ŚBM 6.5.3.4, 10.5.5.1). The knowledge of the Vedas is endless, compared to them, human knowledge is like mere handfuls of dirt (TB 3.10.11.3-5). The universe itself was originally encapsulated in the three Vedas (ŚBM 10.4.2.22 has Prajapati reflecting that "truly, all beings are in the triple Veda").

Vedanta

While contemporary traditions continued to maintain Vedic ritualism (Shrauta, Mimamsa), Vedanta renounced all ritualism and radically re-interpreted the notion of "Veda" in purely philisophical terms. The association of the three Vedas with the bhūr bhuvaḥ svaḥ mantra is found in the Aitareya Aranyaka: "Bhūḥ is the Rigveda, bhuvaḥ is the Yajurveda, svaḥ is the Samaveda" (1.3.2). The Upanishads reduce the "essence of the Vedas" further, to the syllable Aum (ॐ). Thus, the Katha Upanishad has:

- "The goal, which all Vedas declare, which all austerities aim at, and which humans desire when they live a life of continence, I will tell you briefly it is Aum" (1.2.15)

The Vedas in post-Vedic literature

Vedanga

Six technical subjects related to the Vedas are traditionally known as vedāṅga "limbs of the Veda". V. S. Apte defines this group of works as:

"N. of a certain class of works regarded as auxiliary to the Vedas and designed to aid in the correct pronunciation and interpretation of the text and the right employment of the Mantras in ceremonials."[50]

These subjects are treated in Sutra literature dating from the end of the Vedic period to Mauryan times, seeing the transition from late Vedic Sanskrit to Classical Sanskrit.

The six subjects of Vedanga are:

- Phonetics (Śikṣā)

- Meter (Chandas)

- Grammar (Vyākaraṇa)

- Etymology (Nirukta)

- Astronomy (Jyotiṣa)

- Ritual (Kalpa)

Puranas

A traditional view given in the Vishnu Purana (likely dating to the Gupta period[51]) attributes the current arrangement of four Vedas to the mythical sage Vedavyasa.[52]. Puranic tradition also postulates a single original Veda that, in varying accounts, was divided into three or four parts. According to the Vishnu Purana (3.2.18, 3.3.4 etc) the original Veda was divided into four parts, and further fragmented into numerous shakhas, by Vishnu in the form of Vyasa, in the Dvapara Yuga; the Vayu Purana (section 60) recounts a similar division by Vyasa, at the urging of Brahma. The Bhagavata Purana (12.6.37) traces the origin of the primeval Veda to the syllable aum, and says that it was divided into four at the start of Dvapara Yuga, because men had declined in age, virtue and understanding. In a differing account Bhagavata Purana (9.14.43) attributes the division of the primeval veda (aum) into three parts to the monarch Pururavas at the beginning of Treta Yuga. The Mahabharata (santiparva 13,088) also mentions the division of the Veda into three in Treta Yuga.[53]

Other "Vedas"

The term upaveda ("secondary knowledge") is used in traditional literature to designate the subjects of certain technical works.[54][55] They have no relation to the Vedas, except as subjects worthy of study despite their secular character. Lists of what subjects are included in this class differ among sources. The Charanavyuha mentions four Upavedas:

- Medicine (Āyurveda), associated with the Rigveda

- Archery (Dhanurveda), associated with the Yajurveda

- Music and sacred dance (Gāndharvaveda), associated with the Samaveda

- Military science (Shastrashastra), associated with the Atharvaveda

But Sushruta and Bhavaprakasha mention Ayurveda as an upaveda of the Atharvaveda. Sthapatyaveda (architecture), Shilpa Shastras (arts and crafts) are mentioned as fourth upaveda according to later sources.

Some post-Vedic texts, including the Mahabharata, the Natyasastra and certain Puranas, refer to themselves as the "fifth Veda".[56] The earliest reference to such a "fifth Veda" is found in the Chandogya Upanishad. "Dravida Veda" is a term for canonical Tamil Bhakti texts.

Notes

- ^ see e.g. MacDonell 2004, p. 29-39; Sanskrit literature (2003) in Philip's Encyclopedia. Accesed 2007-08-09

- ^ see e.g. Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3; Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 68

- ^ Apte, pp. 109f. has "not of the authorship of man, of divine origin"

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 887

- ^ Muller 1891, p. 17-18

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 82

- ^ Chahal, Dr. Devindar Singh (2006). "Is Sikhism a Unique Religion or a Vedantic Religion?". Understanding Sikhism - The Research Journal. 8 (1): 3–5.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Aad Guru Granth Sahib. Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, Amritsar. 1983.

- ^ Monier-Williams 2006, p. 1015; Apte 1965, p. 856

- ^ see e.g. Pokorny's 1959 Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch s.v. u̯(e)id-².

- ^ Holredge 1995, p. 7

- ^ For written texts during second century BCE see: Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 69; For composition and oral transmission for "many hundreds of years" before being written down, see: Avari 2007, p. 76.

- ^ 1996, p. 37)

- ^ Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 68

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 69.

- ^ 37,575 are Rigvedic. Of the remaining, 34,857 appear in the other three samhitas, and 16,405 are known only from Brahmanas, Upanishads or Sutras)

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 69.

- ^ For a table of all Vedic texts see Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 100–101.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3; Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 68

- ^ MacDonell 2004, p. 29-39

- ^ Witzel, M., "The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools : The Social and Political Milieu" in Witzel 1997, p. 257-348

- ^ For Rig Veda as the "oldest significant extant Indian text" see: Avari 2007, p. 77.

- ^ For 1,028 hymns and 10,600 verses and division into ten mandalas, see: Avari 2007, p. 77.

- ^ For characterization of content and mentions of deities including Agni, Indra, Varuna, and Surya, see: Avari 2007, p. 77.

- ^ For composition over 500 years dated 1400 BCE to 900 BCE, see: Avari 2007, p. 77.

- ^ India: What Can It Teach Us: A Course of Lectures Delivered Before the University of Cambridge by F. Max Müller; World Treasures of the Library of Congress Beginnings by Irene U. Chambers, Michael S. Roth.

- ^ Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 68.

- ^ Drews, Robert (2004). Early Riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe. New York: Routledge. p. 50.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 981.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 51.

- ^ For 1875 total verses, see numbering given in Ralph T. H. Griffith edition. Griffith's introduction mentions the recension history for his text. Repetitions may be found by consulting the cross-index in Griffith pp. 491-99.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 271.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 37.

- ^ Mayrhofer, EWAia I.60

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 37.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 37.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Witzel, Michael, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: Flood 2003, p. 76.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Zaehner 1966, p. vii.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 42.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 387.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 111 dates it to the 4th century CE.

- ^ Vishnu Purana, translation by Horace Hayman Wilson, 1840, Ch IV, http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/vp/vp078.htm

- ^ Muir 1861, pp. 20–31

- ^ Monier-Williams 2006, p. 207. [1] Accessed 5 April 2007.

- ^ Apte 1965, p. 293.

- ^ Sullivan 1994, p. 385

References

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965), The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary (4th revised & enlarged ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0567-4

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help). - Avari, Burjor (2007), India: The Ancient Past, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Flood, Gavin (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43878-0

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Flood, Gavin, ed. (2003), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Malden, MA: Blackwell, ISBN 1-4051-3251-5

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Holdrege, Barbara A. (1995), Veda and Torah, SUNY Press, ISBN 0791416399

- MacDonell, Arthur Anthony (2004), A History Of Sanskrit Literature, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 1417906197

- Michaels, Axel (2004), Hinduism: Past and Present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08953-1

- Monier-Williams, Monier, ed. (2006), Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary, Nataraj Books, ISBN 18-81338-58-4.

- Muir, John (1861), Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and Progress of the Religion and Institutions of India (PDF), Williams and Norgate

- Muller, Max (1891), Chips from a German Workshop, New York: C. Scribner's sons.

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli; Moore, Charles A., eds. (1957), A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (12th Princeton Paperback ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01958-4.

- Smith, Brian K., Canonical Authority and Social Classification: Veda and "Varṇa" in Ancient Indian Texts-, History of Religions, The University of Chicago Press (1992), 103-125.

- Sullivan, B. M. (1994). "The Religious Authority of the Mahabharata: Vyasa and Brahma in the Hindu Scriptural Tradition". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 62 (1): 377–401.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Witzel, Michael (ed.) (1997), Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora vol. 2, Cambridge: Harvard University Press

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Zaehner, R. C. (1966), Hindu Scriptures, London: Everyman's Library

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Literature

- Overviews

- J. Gonda, Vedic Literature: Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas, A History of Indian literature. Vol. 1, Veda and Upanishads (1975), ISBN 9783447016032.

- J. A. Santucci, An Outline of Vedic Literature (1976).

- S. Shrava, A Comprehensive History of Vedic Literature — Brahmana and Aranyaka Works, Pranava Prakashan (1977).

- Concordances

- M. Bloomfield, A Vedic Concordance (1907)

- Vishva Bandhu, Bhim Dev, S. Bhaskaran Nair (eds.), Vaidika-Pāda-Nukrama-Koṣa: A Vedic Word-Concordance, Vishveshvaranand Vedic Research Institute, Hoshiarpur, 1963-1965, revised edition 1973-1976.

- Conference proceedings

- Griffiths, Arlo and Houben, Jan E. M. (eds.), The Vedas : texts, language & ritual: proceedings of the Third International Vedic Workshop, Leiden 2002, Groningen Oriental Studies 20, Groningen : Forsten, (2004), ISBN 90-6980-149-3.

S A K S I

- 63, 13th Main, 4th Block East, Jayanagar, Bangalore - 560011 [India]

Tel/Fax: 080-22456315, Mobile: 93412 33221 Email: info@vedah.com Web: http://www.vedah.org

Publications on Veda

- The Four Veda Overviews: 10,20, 27, 32

- Complete Sanskrit texts: 1,11

- Books with very little Sanskrit: 3, 7, 13,14, 15, 22, 17, 36,

- Detailed translations: 2,4,5,18,37,38,39,40,41,42

- Deities, Mantras and explanation: 6,8,9,12, 16, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35

1. Rig Veda Mantra Samhita (Pp. xiv + 962; $ 50) An user-friendly and aesthetically produced edition. *Text of the entire Rig Veda Samhita *Text of the Rig Veda Khila Suktas *List of popular Suktas and Mantras

- Essays to understand Vedic lore

- Topical index of contents of Mantr¢s

- Ashtaka, adhyaya and mandala concordance

- Concordance with Yajur Veda Samhita.

2. Secrets of Rig Veda: First 121 sukta (Pp. xxii + 639; $ 40) This book contains the first 121 sukt¢s (or 1370 mantras) of the Rig Veda Samhit¢. This is the first book in which the text of all the 1370 mantr¢s is given both in Devan¢gari and Roman scripts. The original text is split into separate words using the traditional pada-p¢°ha with some modifications. The English meaning of every Sanskrit word (in Roman script) is given below the Sanskrit word. 3. Why Read Rig Veda? (Pp. vi + 90 ; $ 4) The book emphasises the universal values which are upheld in Rig Veda like liberty and equality for one and all in society. 4. Kri¾h´a Yajur Veda Taittir¤ya Samhit¢ (3 Volumes Set ; $ 120) This translation is unique in several ways. This is the first time that the Devanagari text, transliteration and the English translation are printed side by side. The format is so arranged that the meaning of each word can be figured out with relative ease. 5. KYTS Mantras (Pp. xv + 579 ; $ 45) Text in Devanagari with transliteration and English Translation. This is the first ever attempt to print only mantras from Krishna Yajur Veda Taittirya Samhita leaving aside the Brahmana (ritual expositions) portion. 6. Sarasvati - Goddess of Inspiration in Rig Veda (Pp. iv + 60 ; $ 2) Sarasvati is the goddess of inspiration in all the Vedas. Rig Veda has 72 mantras dedicated to her. Even though many persons prize inspiration, its nature is vague to most persons. Inspiration is a power of a Truth which leads to a perfect action pervaded by beauty and harmony. This power is useful to all professionals and it can be developed by following the hints given in the Rig Veda Mantras. Of course the level of inspiration developed by a person depends on his/her efforts and aptitude. The associated mantras from the Rig Veda with an explanation of their meanings in English is given. Contemplation of these mantras with faith and their chanting will lead to the development of the power of inspiration. 7. The Light of Veda - A practical approach (Pp. xvi + 70 ; $ 2) It helps to understand the hidden meaning in the mantras, gives a glimpse of vedic literature. 8. How to Manifest Bliss (from Rig Veda) (Pp. vi + 34 ; $ 1) This book explains about 38 mantras from Rig Veda dealing with the manifestation of bliss in everyone. It contains four chapters. The first chapter deals with the knowledge needed for getting bliss. The key idea is the openness for all knowledge and not dwelling on negative thoughts and limitations. Each one of us is infinite. The second chapter deals with the doctrine of bliss which includes the prayer stating why we should live long. The third chapter deals with the methods of manifesting and sustaining the bliss in us. This section has many popular mantras such as Gayatri Mantra, Tryambaka mantra for Shiva-Rudra, the morning mantras for both the spiritual and physical Sun. Chapter four indicates some preparations needed for the manifestation of bliss. It includes the mantras for the purification of our mental apparatus using the divine energies called as waters. The associated mantras from the Rig Veda with an explanation of their meanings in English is given. Contemplation of these mantras with faith and their chanting will lead to the development of the associated psycholigal powers. 9. Rudra Mantr¢s (From Taittiriya Samhita) Namaka, Chamaka, Shiva-Sankalpa, Inner Yajna and Supar´a (with Text & Roman Transliteration). (Pp. viii +136; $ 6) This commentary helps the aspirants to lead a happy life overcoming the obstacles. 10. Essentials of Atharva Veda (Pp. vi +105 ; $ 5) Essays on the unique principles of education, health, longevity, v¢stu, polity and governance, selection of spouse, marriage etc. 11. Kri¾h´a Yajur Veda Taittir¤ya Samhit¢ (Complete Text in Devan¢gari) (Pp. xii + 404 ; $ 20) Elegant format, hard-bound, user-friendly fonts. 12. Prayers (Sanskrit text, transliteration and translation) (Pp. iv + 44 ; $ 2) The prayers, in this book are meant for those who are interested in cultivating a direct relationship with the Divine. Composed by T.V.Kapali Sastry. 13. Pr¢´¢y¢ma with Postures - for Specific Benefits (Pp. viii + 60 ; $ 5) The book helps to learn the art of breathing for healthy living and well being. 14. Work, Enjoyment and Progress (Pp. x+142; $ 7)

A series of essays in question-answer format intended to enrich the creativity and enhance the quality of life.

15. Veda, Upanishad and Tantra in Modern Context (Pp. iv + 76; Price $ 2) The book answers some key questions: (i) what are the various books in the collection called Vedas in the broad sense of the word? (ii) What is the relevance of these texts to the modern seekers? (iii) Does this core of the Vedas indicate new paths of spiritual knowledge? (iv) Are there other modes of knowledge besides intellectual knowledge made familiar to most of us because of advances made by western science and technology?

16. Shanti Mantras-From the Upanishads and Veda Samhitas (Pp. xiv + 58 ; Price $ 3); The Shanti mantras help us to have close association with the cosmic powers and to lead a creative and harmonious life. In some periods of our life we feel peaceful. Later, we feel that the peace has left us. The problem is that, we are systematically squandering the power of peace without replenishing. The varieties of mantras in this book help us in establishing the plenitude in us.

17. Essence of Tantra (Pp. vi + 58 Price : $ 3 ) : The fundamental thought of the Tantra can be traced to the veda in general and Rig veda in particular. The occult truth in the Veda are elaborated in the Tantrik texts.

This book explores certain aspects of tantra and their relevance to everyday life. It also tries to answer some questions posed often.

18. Divinizing Life: The Path of Atri Rishi in Rig Veda (Pp. xxi + 350; $ 30) (Text, transliteration, translation & notes of all 727 mantras of Fifth Mandala of Rig Veda); Has also the Shri-sukta. It helps one to understand the spirit and thrust of RigVeda in viewing life as a journey towards light without neglecting the realities of transactional existence. 19. Veda Mantr¢s and S¦ktas - Widely used in Worship (Pp. ix + 149 ; $ 5) Purusha Sukta, Shri Sukta, Vishnu Sukta, Navagraha mantra, Vastu mantra, Bhu Sukta, Durga Sukta, Sarasvati Sukta, Pavamana Sukta, Mantra Pushpa and several other mantras used in house & temples. The mantras are given along with the meaning and notes. 20. Essentials of Krishna & Shukla Yajur Veda (Pp. ix + 166 ; Price: $ 7). The focus of this book is on the Light that Yajur veda gives us to enrich the human potential and enhance the quality of life. The book contains key ideas contained in two recensions (Shakha) of Yajur Veda, Taittiriya Samhita from the Krishna Yajur veda and Vajasaneyi samhita from Shukla Yajur Veda.

21. Lights on the Upani¾hads

(Pp. x + 196 ; $ 10)

The author Sri T. V. Kapali Sastry has presented the vision and ecstacy of spiritual experience hidden in the Upanishads. 22. Symbolism of Marriage (Pp. vi + 60; $ 1) The meaning and process of marriage as envisaged in Hindu culture. 23. Om - the Ultimate Word

(Pp. iv + 56; Price: $ 3)

Om is a patent word. Om is a one-lettered mantra. Om is the foothold of man. Om is transcendental. Transformation is possible through Omkara. Omkara leads to enlightenment. Brief and specific information on above mentioned matter is covered in this book. 24. Soma - The Delight of Existence in Rig Veda (Pp. viii + 36; $ 1) The mantras in this book will help us to know about Soma deva and interact with him. 25. Ganapati - Brahmanaspati & Kumara in Vedas (Pp. vi + 58 ; $ 3) This book contains several mantras both from the Rig Veda Samhita, Yajur Veda Samhita and the Upanishads invoking the deity Brahmanaspati and Ganapati.

26. Secrets of Effective Work: Agni's Guidance in Rig Veda (Pp. viii + 40; Price: $ 3) This book gives the psychological powers associated with the cosmic power Agni which are useful for everyone in everyday life, especially in all sorts of works done in waking hours. This book focuses on how to develop the psychological powers within us such as the will-power. The book quotes more than one hundred mantras from Rig veda Samhita and Yajurveda Samhita in support of the ideas delineated here. The book focuses on the performance of work aimed at perfection. 27. Essentials of Rig veda (with the text, translation and explanation of 62 Mantras) (Pp. ix + 79; Price $ 5) This is a book on Rig Veda summarizing the key ideas in its ten Mandalas. The book is divided into three parts. They are: I. Overviews, II. Topics and mantras addressed to them, III. Topics and Associated mantras. Apart from this, separate overviews of all the ten mandalas are given in one chapter. The book has 44 chapters. 28. Indra, Lord of Divine Mind in Rig Veda (Veda Mantras for manifestation of Mental Powers in us ) (Pp. iv + 40; Price: $ 2) Rig Veda has about 2,500 mantr¢s dedicated to the God Indra out of the total of 10,552 mantr¢s. Indra can be understood only if we study all of them (or most of them) and meditate on them. This book describes the powers of Indra relevant for us today using about one hundred mantr¢s from the Rig Veda and Yajur Veda. 29. Agni in Rig Veda - First 300 Mantras from 12 Rishis (Pp. xvi + 192 ; Price $ 9) This book contains the text, transliteration, translation and commentary of all the 315 mantr¢s in the first 34 S¦kt¢s dedicated to Agni in the first Ma´²ala and in the 2 other S¦kt¢s of the First Ma´²ala of Rig Veda. The translation is based on the Sanskrit commentary of Sri Kapali Sastry entitled, "Siddh¢njana' and also Sri Aurobindo's insights contained in his two books, "The Secret of the Veda' and "Hymns to Mystic Fire'. There are notes on potentials within us, the wisdom behind them and how to develop these inner powers. This aspect is the focus of this book. 30. Internal Yaj®a (Pp. viii + 48; $ 1) Spiritual interpretation of Rig Veda and Krishna Yajur Veda Taittiriya Samhita. 31. Hymns on creation and Death in Veda

(PP vii + 88; Price $ 5)

This collection has 124 rik mantr¢s (119 from Rig Veda and 5 from Upani¾hads), four prose mantr¢s from the Upani¾hads and passages from Shatapatha Br¢hma´a and Taittir¤ya ¡ra´yaka. It is divided into three parts. Part I has the S¦kt¢s primarily dealing with creation in one form or another. It includes the famous Puru¾ha S¦kta which is in Rig Veda and Yajur Veda. It includes the S¦kta (10.72) entitled "The Birth of Gods'. The part II deals with the Word, which is the agency from which creation actually proceeds. It has 2 s¦kt¢s including the V¢k S¦kta. The topic of creation cannot be separated from the topic of destruction. The B¨had¢ra´yaka U. mantra on creation mentions the maxim, "Hunger that is death'. The famous phrase from the Taittir¤ya Upani¾had, "Eater is eaten' (¢dyena atti, Tai. U. 2.3) indicates the intimate connection. Part III deals with Death viewed in the broad sense of the word.

32. Essential of Samaveda and Its Music

(Pp. vii + 60; Price $ 5)

This book has 32 chapters divided into 3 parts. The Part I having 10 chapters deals with the general information regarding the texts, ri¾his, translators, connection to Upani¾hads and Rig Veda etc. Part II delineates some aspects of S¢ma Veda related to music. Even though the information given here is not original, the presentation of this body of knowledge in a compact form is a highlight of this book. The chapter 19 is particularly interesting because of the use of relatively advanced mathematics in devising a scheme for detecting the errors in the pronunciation of accents during chanting. One of the section in the book deals with the psychological powers associated with the various deities occurring in S¢ma mantr¢s and the text and meaning of the associated mantr¢s. Note that symbolism is an integral part of the meaning behind these mantr¢s. The psychological powers associated with the deities such as the will-power, clarity of mental operations, inspiration can be developed with the help of these mantr¢s. Understanding the meanings of words in a mantra and their deeper meanings is of great help in this process. 33. Purusha Sukta (Pp. viii + 87; Price : $ 5) This is a book by the eminent scholar, Veda Kamala Professor S.K. Ramachandra Rao. Puru¾ha S¦kta is the most well-known hymn in all the Ved¢s. But its deep meaning has not been explained in some detail anywhere using the traditional sources. In his preface to the first edition, author states that "the idea of the Puru¾ha has been explained in some detail and the enigmatic concept of Puru¾ha-medha has also been considered in its proper perspective. It is hoped that by presenting this traditional interpretation, many of the misconception will be removed.' The author's great contribution is excerpts from the Veda books such as the massive "Shatapatha Br¢hma´a, Taittir¤ya ¡ra´yaka, Taittir¤ya Br¢hma´a and other Upani¾had and Br¢hma´a books. The concept of Puru¾ha has been discussed in some detail by all the major Upani¾hads, and this fact is not widely known. This book contains many of the relevant excerpts and their translation. Another great contribution is the handling of the topic of Creation and Praj¢pati. The author is concerned here with the simplistic views of these topics in the Pur¢´a. But the Br¢hma´a and ¡ra´yaka books throw a wealth of light on this topic. 34. Wisdom of Atharva veda (Hymns to Earth, Education, Skambha, Wedding, Family, Body structure, Healthy longevity and epigrams) ( Pp viii + 80; Price $ 5)

This book contains the text and translation of about 150 mantras from Atharva Veda Samhita. This book compliments our another publication, " Essentials of Atharva veda'.

35. Semantics of Rig Veda (Pp. ix + 188; Price $ 12) This book is designed to help the beginners in the study of Veda mantr¢s to understand the meanings of the individual words and the phrases in Veda mantr¢s. The chapters three to nine deal with the individual words. A beginner needs to become familiar with at least 500 words. The words are divided into 10 groups, each group dealing with one topic. For instance, the group A1 given in chap. 5 gives over sixty words dealing with mental operations and consciousness. The idea of keywords in RV is introduced. These words in RV occur in many mantr¢s, say at least 100. Clearly if we make a mistake in assigning a meaning to a keyword, we are making mistakes in at least 100 places. In chapter 9, the author discuss 60 families of words, each family consisting of words which sound similar but are different in meaning. The author refers frequently to the double meaning of words, one is its surface meaning, the other is its deep meaning.

36. A New Light on the Veda (Based on the Traditional and modern Sources) (Pp. xxvii + 153; $ 12) This book gives an excellent picture of the spiritual/ psychological viewpoint of veda from ancient times like those of Brahamana books to the middle of twentieth century. Specifically it stresses the importance of both the chanting of the mantra and the understanding of their meaning. The book has five sections, namely I. overview II. Yajna, mimasa and the scret revealed by mantras III. Nirukta, Brihed - devata, Brahamana and Upanishads IV. Resuscitating the Spritual view in the 2nd Millenium: Ananda Teertha; V. Deities.

This is a magnificent work by Sri T. V. Kapali sastry (1886-1953). He was a multiple personality. Among his several services to the national heritage, the one which comes most prominently to the mind is his solid contribution in building a strong bridge between the ancient past and the evolutionary thought of the present.

37. Rig Veda: Tenth Mandala

(Pp. xix + 582; Price: $ )

Among the ten Mandalas of Rig Veda, tenth Mandala has considerable attraction for many persons since it contains several suktas which are widely used or widely referred to such as the Purusha Sukta, the hymn of creation, the hymn of the Goddess of speech (vak), the suktas dealing with health and healing etc. The book contains all the 1754 mantras pertaining to 191 Suktas of the tenth Mandala along with the text, translation and explanation. Along with this book, a booklet of 33 pages containing introductory essays, "The Basics of Rig Veda' is given.

38. Rig Veda: Third Mandala

The translation of all the 617 mantr¢s in the 62 S¦kt¢s of the Third Ma´²ala of Rig Veda along with the text and some explanation. All the mantr¢s of this Ma´²ala are associated with the Ri¾hi Vishv¢mitra or his father G¢thi Kaushika or the sons of Vishv¢mitra.

As in our all SAKSI publications, the focus is on the wisdom in the Veda conveyed by the spiritual/psychological meanings of the mantr¢s. The primary aim of our book is to make the translation understandable to lovers of Veda in all walks of life, not limited to academics or the experts in English language. The translation follows the paradigm described in detail in our earlier books, "Rig Veda Samhit¢: Tenth Ma´²ala' and "Rig Veda Samhit¢: Fourth Ma´²ala. It is needless to say that the meanings of many words in the mantr¢s, assigned by Sri Aurobindo are quite different from those found in the commentary of S or the translations of Indologists. Sri Aurobindo made a deep study of the Sansk¨t of the Veda mantr¢s which is very different from the classical Sansk¨t. This study coupled with his intuition regarding the secrets in the Veda helped him to reveal the correct meanings of the words given here. In the appendix 9 of this book, we mention the meanings of some of the important words in the mantr¢s. We request and urge our readers to read the first 2 essays in the Part II of the book, Appendices, whose titles are listed here: 1. The Basic ideas in Rig Veda 2. Insight into the journey of inner yajna (workings of Agni and Indra) The reading will greatly help the reader in understanding the contents of Ma´²ala 3. Note that our compact book, "Essentials of Rig Veda' gives an excellent overview of several aspects of Veda including mantra, metre, rishis, power of deities and some of the interesting topics in it.

39. Rig Veda: Fourth Mandala Translation of all the 589 mantr¢s in the 58 S¦kt¢s of the Fourth Ma´²ala of Rig Veda along with the text and some explanation. As in all SAKSI publications, the focus is on the wisdom in the Veda conveyed by the spiritual/psychological meanings of the mantr¢s. The primary aim of our book is to make the translation understandable to lovers of Veda in all walks of life, not limited to academics or the experts in English language. The translation follows the paradigm described in detail in the introduction to, "Rig Veda Samhita: Tenth Ma´²ala'

40. Rig Veda: Six Mandala Translation of all the 765 mantr¢s in the 75 S¦kt¢s of the Sixth Ma´²ala of Rig Veda along with the text and some explanation. As in our earlier SAKSI publications, the focus is on the wisdom in the Veda conveyed by the spiritual/psychological meanings of the mantr¢s. The primary aim of our book is to make the translation understandable to lovers of Veda in all walks of life, not necessarily academics or the experts in English language. The translation follows the paradigm described in detail introducing "Rig Veda Samhita: Tenth Ma´²ala'.

41. Rig Veda: Seventh Mandala Translation of all the 841 mantr¢s in the 104 S¦kt¢s of the Seventh Ma´²ala of Rig Veda along with the text and some explanation. All the mantr¢s of this Ma´²ala are associated with the Ri¾hi Vasi¾h°ha. As in all SAKSI publications, the focus is on the wisdom in the Veda conveyed by the spiritual/psychological meanings of the mantr¢s. The primary aim of our book is to make the translation understandable to lovers of Veda in all walks of life, not limited to academics or the experts in English language. The translation follows the paradigm described in detail in the introduction to the book, "Rig Veda Samhit¢: Tenth Ma´²ala'.

(Sanskrit/English Publications 37 (available) + 4 (O.P.) = 41)