Rigveda

The Rig Veda ( Vedic , Sanskrit ऋग्वेद Rgveda m., From veda , knowledge ' , and RC , German, Verses') is the oldest part of the four Vedas , making it one of the most important writings of Hinduism .

The term is often used for the Rigvedasamhita , the core of the Rigveda, although this actually comprises a larger collection of texts. The Rigvedasamhita is a collection of 1028 (according to other counts 1017) hymns, divided into ten books, called mandalas (song circles ).

In addition to the Rigveda, the four Vedas also include Samaveda , Yajurveda and Atharvaveda . All Hindu religions accept the inviolability of these four Vedas, but individual beliefs often add other scriptures to them.

Like all Vedas, the entire Rig Veda consists of several layers of text, of which the Samhitas and the hymns form the oldest. The Brahmanas , the next layer of text, consist primarily of ritual texts. Then come the forest texts called Aranyakas , and finally the Upanishads , which for the most part contain philosophical treatises. While the language of the hymns is Vedic , the final layers are written in Sanskrit .

Historical and geographical context

The time of origin of the Rksamhita is in the dark and has therefore always been the subject of speculation. Speculations that based on astronomical information in the Rigveda this was 6000–4000, 8000 or even 12,000 BC. Chr., Or based on geological information dating back to the Pliocene , are incompatible with today's knowledge of the history of language and with the social structure assumed in the Rigveda in view of archaeological findings. According to the current state of Indo-European Studies and Indology , a date of origin appears in the second half of the second millennium BC. BC as likely, whereby books II to IX were written earlier than books I and X. Individual hymns can be a few centuries older.

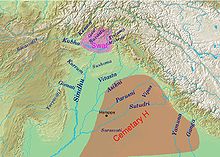

The oldest layers of the Rigveda Samhita are among the most original texts in an Indo-European language , perhaps of a similar age to texts in the Hittite language . Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that most of the Rigveda Samhita originated in the northwest region of the Indian subcontinent, most likely between 1500 and 1200 BC. Chr.

The poets of these hymns from priestly families are people of one people who called themselves Aryans . Their language is related to Avestan and Old Iranian; In terms of content, too, the poems of the Rigveda and the oldest sacred poetry of Iran touch each other . During the creation of the Rig Veda, the Indo-Aryans are said to have immigrated to the Indus Valley , today's Punjab . In Afghanistan and western Punjab, the livestock-dependent people depended on rain and water from rivers, especially when the snowmelts. This is why the life-giving rain and its bringers, the storm gods, the Maruts , are sung in many hymns .

In RV 10.75 An der Rivers , 18 rivers are listed with their Rigvedic names, interestingly in the order from east to west, then from north to south. Among them it is above all the Sindhu (Indus) and its tributaries, which are praised by the singers for their amount of water.

The Vedic tribes are said to have been semi-nomads who had bullock carts, horse-drawn carts and bronze weapons. The sacrificial ceremonies took place in the great outdoors. In contrast to later Hinduism, they are said not to have had images of gods or statues.

Structure and content

While the first circle of songs contains the works of 15 Rishis , the mandalas or circles of songs two to seven represent the traditions of certain families or clans who have passed on the poetry to generations. These so-called 'family song circles' contain the oldest core of the Rig Veda. The song circles one and ten are accordingly considered to be younger. The ninth circle of songs deals exclusively with songs that are linked to the making of the somatopotion and the soma offering. In the tenth circle of songs, group songs and individual songs are combined that cannot be clearly assigned or that were composed for specific, special occasions.

| song cycle | family | Number of songs |

|---|---|---|

| First circle of songs | Different authors | 191 |

| Second circle of songs | Book of Grtsamadas | 43 |

| Third circle of songs | Book of the Visvamitras | 62 |

| Fourth circle of songs | Book of the Vamadevas | 58 |

| Fifth circle of songs | Book of the Atris | 87 |

| Sixth circle of songs | Book of the Bharadvajas | 75 |

| Seventh circle of songs | Book of the Vasisthas | 104 |

| Eighth circle of songs | Book of small groups of poets | 103 |

| Ninth circle of songs | Soma Pavamana songs | 114 |

| Tenth circle of songs | The big addendum | 84 |

| Single songs | 107 |

The Rigveda contains those texts that are important for the Hotri ("caller"), one of the priests in the Vedic sacrificial cult . They are songs of praise to gods like Agni , Indra or Varuna . These existed, under similar or completely different names, with other peoples of the Indo-European or Indo-European language group .

According to the Shatapatha Brahmana , the Rigveda consists of 432,000 syllables, which corresponds to the number of muhurtas (1 day has 30 muhurtas ) in 40 years. This statement emphasizes the underlying philosophy of the Vedas of a connection between astronomy and religion.

Deities

The focus of the Rigveda religion is on fire and animal sacrifice. Therefore, the first hymns of each song circle are addressed to Agni , the god of fire, who as messenger of the gods leads the host of gods to the place of sacrifice (example: RV 1,1.). Most of the hymns, however, are for Indra , who with his great deeds freed the water and brought out the sun, the sky and the dawn (example: RV 1, 32). He once stole the soma and freed the cows. He is considered a great drinker of Soma, which gives him irresistible strength.

Standing behind the natural phenomena, certain deities are invoked in the hymns: Ushas , the dawn and daughter of heaven, who drives away the darkness (examples: RV 7,75-81); Surya , the sun god (example: RV 1.50); Vayu , the wind god (example: RV 1,134 and 135); Parjanya , the rain god, who together with the Maruts , the thunderstorms, brings the invigorating rain (example: RV 5,83,4). Soma, the drink and the plant are sometimes addressed as gods (RV 9th song circle).

The Adityas , the sons of the Aditi, form a group of gods . They form a group of seven or eight gods (later twelve) of which six are named. They represent the embodiment of ethical principles: Mitra , the god of contract, watches over the sanctity of the contract word; Varuna , the god of the word of truth, is the maintainer of law and order in the cosmos, on earth and in society; Aryaman , the god of the hospitality contract, watches over the hospitality.

The divine twins, the Ashvins , are among the gods of protection who are invoked in times of need . They are called for help in a number of hymns, or they are thanked for wonderful salvations and healings (example: RV 1,157,4 or RV 1,158,3). Often several deities are invoked together in the individual hymns, and there are individual hymns that address all gods (examples: RV 7,34 - 55).

Individual hymns

While most hymns are addressed to one or more deities, there are also those in which statements are made about the origin and order of the world. That's what it says in RV. 10.90:

"

- Purusa is a thousand heads, a thousand eyes, and a thousand feet ; it completely covered the earth and rose ten fingers above it.

- Purusa alone is this whole world, the past and the future, and he is the master of immortality (and also of that which grows through food).

- Such is its greatness, and Purusa even greater than this. A quarter of him are all creatures, three quarters of him is immortal in heaven. "

This idea of Purusha is carried further in the Upanishads , which emerged many centuries later.

The first reference to the caste system is found in verse 12 of this hymn :

"His mouth became a Brahmin , his two arms were made into Kshatriyas , his two thighs into Vaishya , and Shudra arose from his feet ."

This is only so clearly stated here in the entire Rigveda. Although it is a late book, it can be assumed that at that time the caste system in social life was not fully developed. The mythological legitimation of social stratifications is remarkable here.

Knowledge transfer

The texts of the Rigveda are written orally, without knowledge of the scriptures, and have been passed down from father to son and from teacher to student for at least three millennia. The belief that only the precisely recited poet's word produces the power that dwells in it has resulted in a faithful tradition that cannot be found anywhere else, which by far exceeds that of the classical or biblical texts. The accuracy is so great that one can think of a type of sound recording from around 1000 BC. Can speak. The knowledge of the Vedas was considered a power, which is why it was not written down, even when the scriptures already existed, as it was feared that this power could fall into the wrong hands.

Comments and translations

In the 14th century, Sayana was one of the first to write a detailed commentary on the Rig Veda. The most common edition (in Latin transcription) is that of Theodor Aufrecht (Leipzig 1861–1863). German translations: Hermann Graßmann (Leipzig 1876, two volumes, metric, reprinting unchanged: Minerva-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1990), Alfred Ludwig (Prague 1876–1888, six volumes , prose) and Karl Friedrich Geldner (1923). In the meantime a complete translation into Russian by Tatjana Elizarenkova (Moscow 1989–1999) is available, in which the more recent research literature up to around 1990 is taken into account.

literature

- Michael EJ Witzel , Toshifumi Goto: Rig-Veda: The Holy Knowledge, First and Second Circle of Songs , Verlag der Welteligionen, 2007, ISBN 978-3-458-70001-2 .

- Salvatore Scarlata, Toshifumi Goto, Michael EJ Witzel: Rig-Veda: The holy knowledge, third to fifth circle of songs , Verlag der Welteligionen, 2013, ISBN 978-3-458-70042-5 .

- Karl Friedrich Geldner : Rig-Veda: Das Heilige Wissen Indiens , 1923, complete translation, newly published by Peter Michel, Marix-Verlag, 2008, ISBN 978-3-86539-165-0 .

- Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty: The Rig Veda. New Delhi 1994.

- Alfred Ludwig: Alfred Ludwig's English translation of the Rigveda (1886-1893). Part 1: Books I – V. Edited by Raik Strunz. [Publications of the Indological Commission of the Academy of Sciences and Literature, Mainz. 6.] Wiesbaden 2019. ISBN 978-3-447-11306-9 .

- Walter Slaje: Where Yama feasts with the gods under a beautiful leafy tree: Bilingual samples of Vedic poetry . [Indologica Marpurgensia. 9.] Munich 2019. ISBN 978-3-87410-148-6 .

- Axel Michaels : Hinduism. Munich 2006.

- Thomas Oberlies: The Rigveda and its religion. Verlag der Welteligionen im Insel Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-458-71035-6 .

- Jutta Marie Zimmermann: Rig-Veda. Impressions from the Rigveda. Hymns of the seers and sages. 1st edition. Raja Verlag, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-936684-12-4 .

Web links

- sacred-texts.com - Text of the Rigveda (English translation)

- sanskritweb.net (Rigveda in Devanagari)

- thombar.de (German translation)

- detlef108.de (Rigveda in ITRANS, Devanagari and Transliteration)

- sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de Hermann Grassman's dictionary for Rigveda, 1873

- deutschelyrik.de Vedic poetry in excerpts as an audio book. Translated into German by Walter Slaje. Voiced by Fritz Stavenhagen

Individual evidence

- ^ Klaus Mylius : History of ancient Indian literature. Wiesbaden 2003, p. 18.

- ^ Richard Mercer Dorson: History of British Folklore , 1999, ISBN 978-0-415-20477-4 , p. 126.

- ^ Gavin D. Flood: An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 37

- ↑ Michael Witzel: Early Sanskritization: Origin and Development of the Kuru state. (1995), p. 4

- ^ David W. Anthony: The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2007, p. 454

- ↑ Michael Witzel, Toshifumi Goto: Rig-Veda. First and second circle of songs. P. 432.

- ^ KF Geldner: Rig-Veda. Volume 1, overview XXIII - XXVIII

- ↑ Michael Witzel, Toshifumi Gotō: Rigveda. P. 455.

- ^ KF Geldner: Rig-Veda II. Book. P. 286.

- ^ KF Geldner: Rig-Veda. II. Book. P. 288 (spelling adapted to the present day).

- ↑ Michael Witzel, Toshifumi Goto: Rig-Veda. Publishing House of World Religions, p. 475.

- ^ Heinrich von Stietencron: The Hinduism. P. 19.