LZ 129 Hindenburg

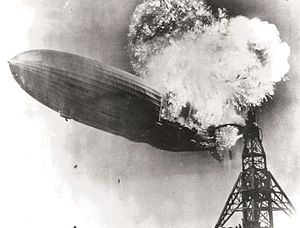

LZ 129 Hindenburg was a German zeppelin that was destroyed by fire while landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey on May 6, 1937. A total of 36 people (about one third of those on board) perished in the accident, which was widely reported by film, photographic, and radio media.

The Hindenburg

The LZ 129 Hindenburg and her sister-ship LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II were the two largest aircraft ever built. The Hindenburg was named after the President of Germany (1924-1934), Paul von Hindenburg. It was a brand-new, all-duralumin design: 245 meters long (804 ft), 41 meters in diameter (135 ft), containing 200,000 cubic meters (7,000,000 ft³) of gas in 16 bags or cells, with a useful lift of 112.1 metric tons force (1.099 MN), powered by four reversible 1,200 horsepower (890 kW) Daimler-Benz diesel engines, giving it a maximum speed of 135 kilometers per hour (84 mph).

The Hindenburg was longer than three Boeing 747s placed end-to-end. It had cabins for 50 passengers (upgraded to 72 in 1937) and a crew of 61. For aerodynamic reasons, the passenger quarters were contained within the body rather than in gondolas. It was skinned in cotton, doped with iron oxide and cellulose acetate butyrate impregnated with aluminum powder. Constructed by Luftschiffbau Zeppelin in 1935 at a cost of £500,000, it made its first flight on March 4, 1936.

The Hindenburg was originally intended to be filled with helium, but a United States military embargo on helium led the Germans to modify the design of the ship to use highly flammable hydrogen as the lift gas. This also gave the craft approximately 10 percent higher lifting capacity.

After the first season in winter 1936/37 several changes were made. Because of the greater lifting capacity, 10 passenger cabins were added. Nine of them had two beds, one four beds. During the first year of service, LZ 129 had a special aluminium Blüthner piano on board in the music salon. The Blüthner grand was the first piano in flight and hosted the first broadcast radio "air concert". It was removed to save weight and was not on board in 1937.

The Germans had experience with hydrogen, and no hydrogen-related fire accidents had occurred on civil Zeppelins, so this switch from helium did not cause alarm. Knowing the risks of hydrogen gas, the engineers used various safety measures, including treating the airship's coating to prevent electric sparks. Such was their confidence in their ability to handle hydrogen that a smoking room was present on the Hindenburg; it was pressurized to keep hydrogen out.

Successful first year

Although popular perception is that the Hindenburg was destroyed on its maiden voyage, in reality the zeppelin had been in service for quite some time before the explosion.

The early career of the Hindenburg built upon the numerous achievements of its predecessor Graf Zeppelin which had already flown for nearly 1 million miles. During 1936, its first year of commercial operation, the Hindenburg flew 191,583 miles carrying 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail. In that year the ship made 17 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean with 10 trips to the US and 7 to Brazil. It also completed a record Atlantic double-crossing in 5 days, 19 hours and 51 minutes in July. The German boxer Max Schmeling was a passenger. He was given a hero's welcome in Frankfurt after defeating Joe Louis.

In May and June 1936 the Hindenburg flew twice over the United Kingdom, primarily the north of England. It has been suggested by the historian Oliver J. Y. Denton in the book The Rose and the Swastika (2001) that the Hindenburg was spying on the north of England.

On the first of August 1936, the Hindenburg was present at the opening ceremonies of the eleventh modern day Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. Moments before the arrival of Adolf Hitler, the airship crossed over the Olympic stadium trailing the Olympic flag from its tail. (Birchall, 1936)

This success led the Zeppelin Company ('Luftschiffbau Zeppelin') to start plans to expand its airship fleet and trans-Atlantic services.

The disaster

Historic newsreel coverage

| Oh, the humanity! | ||

The disaster is remembered partly because of extraordinary newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison's recorded radio witness report from the landing field. The crush of journalists was in response to a heavy publicity push about the first trans-Atlantic Zeppelin passenger flight to the US of the year. (The ship had already made one round trip from Germany to Brazil that year.) Morrison's recording was not broadcast until the next day. Parts of his report were later dubbed onto the newsreel footage (giving an incorrect impression to some modern eyes accustomed to live television that the words and film had always been together). Morrison's broadcast remains one of the most famous in history — his plaintive words "Oh, the humanity!" resonate with the impact of the disaster.

Herbert Morrison's famous words should be understood in the context of the broadcast, in which he had repeatedly referred to the large team of people on the field, engaged in landing the airship, as a "mass of humanity." He used the phrase when it became clear that the burning wreckage was going to settle onto the ground, and that the people underneath would probably not have time to escape it. It is not clear from the recording whether his actual words were "Oh, the humanity" or "all the humanity."

There had been a series of other airship accidents (none of them Zeppelins) prior to the Hindenburg fire, most due to bad weather. However, Zeppelins had an impressive safety record; the Graf Zeppelin had flown safely for more than 1.6 million km (1 million miles) including making the first circumnavigation of the globe. The Zeppelin company was very proud of the fact that no passenger had ever been injured on one of their airships.

The Hindenburg accident changed this. Public faith in airships was shattered by the spectacular movie footage and impassioned live voice recording from the scene. It marked the end of the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airships. This news report is available in the old time radio circles as well. (Although many transfers of this show are very high pitched, there is a compact disc available of the show in its correct pitch.)

Death toll

Most of the crew and passengers survived. Of 36 passengers and 61 crew, 13 passengers and 22 crew died. Also killed was one member of the ground crew, Navy Linesman Allen Hagaman. Most deaths did not arise from the fire but were suffered by those who leapt from the burning ship. (The lighter-than-air fire burned overhead.) Those passengers who rode the ship on its gentle descent to the ground escaped unharmed. What should also be noted is that almost double the number of casualties occurred when the helium-filled USS Akron crashed. [1]

Controversies

As with many historic events, interpretations of the causes are often coloured by politics and polemics.

On the one hand, some speculate that the German government of that era placed the blame on flammable hydrogen in order to cast the U.S. helium embargo in a bad light. Others suggest that present-day proponents of hydrogen as a transportation fuel have forwarded a "flammable fabric" analysis of the fire in order to deflect public concern about the safety of hydrogen.

Nonetheless, there remain three major points of contention: 1) How the fire started, 2) Which material (fabric or gas) started to burn first and 3) Which material (fabric or gas) caused the rapid spread of the fire.

Cause of ignition

Sabotage theory

At the time, sabotage was commonly put forward as the cause of the fire, in particular by Hugo Eckener, former head of the Zeppelin company and the "old man" of the German airships. (Eckener later publicly endorsed the static spark theory — see below.) The Zeppelin airships were widely seen as symbols of German and Nazi power. As such, they would have made tempting targets for opponents of the Nazis.

Another proponent of the sabotage hypothesis was Max Pruss, commander of the Hindenburg throughout the airship's career. Pruss flew on nearly every flight of the Graf Zeppelin until the Hindenburg was ready. In a 1960 interview conducted by Kenneth Leish on behalf of Columbia's Oral History Research Office, he described early dirigible use as safe and felt strongly that the fire was caused by sabotage. Pruss stated that on trips to South America, which was a popular destination for German tourists, both ships passed through multiple thunderstorms with lightning striking the ship without any trouble whatsoever.

Several theories as to who the alleged saboteur may have been have been put forward. In particular, some have alleged that Zionist agents working against increasingly anti-semitic Germany were behind the fire.

In 1962, A. Hoehling published a book entitled Who Destroyed the Hindenburg?. In the book, Hoehling considers and rejects all explanations except sabotage. He alleges that the most likely saboteur is one Eric Spehl, a rigger on the Hindenburg crew who was killed at Lakehurst.

Ten years later, Michael MacDonald Mooney published his own book, The Hindenburg. He, too, alleges that Spehl was the saboteur.

Those putting Spehl forward as the alleged saboteur focus on several historic threads including: the course of Spehl’s own life, his girlfriend’s anti-Nazi connections (she was reportedly a suspected communist opposed to the Nazis); that the fire started near Gas Cell 4 (Spehl’s duty station); the discovery of a dry-cell battery among the wreckage; the fact that Spehl was an amateur photographer familiar with flashbulbs that could have served as an igniter (presumably wired to the above mentioned dry cells); and rumors about Spehl’s involvement dating from a 1938 Gestapo investigation.

However, opponents of the sabotage theory claim that no firm evidence, only suppositions, supporting sabotage as a cause of the fire was produced at any of the formal hearings on the matter. The opponents also claim that the sabotage theory rests on selective use of the available evidence. They point out that Spehl could be viewed as a convenient scapegoat as he died in the fire and was hence unable to refute the accusations made against him. These opponents also believe that the sabotage theory was fostered by the children of Max Pruss in an effort to exonerate their father. They also point out that neither of the postwar memoirs of Eckener nor von Schiller contained any support for the notion of "suppressed investigation findings" and, given the timing of the memoirs, there would be little incentive for these two airshipmen to perpetuate a cover-up of the then fallen Nazi regime. This is particularly true of Eckener who had been extremely vocal in his opposition to the Nazis during their rise to power.

And finally, opponents point to the fact that neither of the formal investigations (American and German) concluded in favor of any of the sabotage theories.

Static spark theory

Although the evidence is by no means conclusive, a reasonably strong case can be made for an alternative theory that the fire was started by a spark caused by a buildup of static electricity. Proponents of the "static spark" theory point out that the airship's skin was not constructed in a way that allowed its charge to be evenly distributed, and the skin was separated from the duralumin frame by nonconductive ramie cords. This may have allowed a potential difference between the wet Zeppelin and the ground to form. In order to make up for a delay of over 12 hours in its trans-atlantic flight, the ship passed through a weather front with a high electrical charge and where the humidity was high (rather than delay its approach). This made the mooring lines wet and therefore conductive. As the ship moved through the air, its skin may have become charged. When the wet mooring lines connected to the duralumin frame touched the ground, they would have grounded the duralumin frame. The grounding of the frame may thus have caused an electrical discharge to jump from the skin to the grounded frame. Some witnesses reported seeing a glow consistent with St. Elmo's fire along the tail portion of the ship just before the flames broke out, although these reports were made after the official inquiry was completed.

Puncture theory

Another popular theory put forward referred to the film footage taken during the disaster, in which the Hindenburg can be seen taking a rather sharp turn prior to bursting into flames. Some experts speculate that one of the many bracing wires within the structure of the airship may have snapped and punctured the fabric of one or more of the internal gas cells. They refer to gauges found in the wreckage that showed that the tension of the wires was much too high. The punctured cells would have allowed hydrogen out of the Hindenburg, which could have been ignited by the static discharge mentioned previously. Advocates of this theory believe that the hydrogen began to leak approximately eight minutes prior to the explosion, building up until the spark ignited the gas. This theory, however, remains speculation, because no concrete evidence has shown that the gas cells were punctured and no witness accounts back up this hypothesis.

Initial fuel for combustion

Most current analysis of the accident assumes that the static spark theory is correct. However, there is still a debate as to whether the fabric covering of the ship or the hydrogen used for buoyancy was the fuel for the fire.

Proponents of the "flammable fabric" or incendiary paint theory (IPT), first posited by Addison Bain in 1997, point out that the coatings on the fabric contained both iron oxide and aluminium-impregnated cellulose acetate butyrate dope. These components were potentially reactive. In fact, iron oxide and aluminium are sometimes used as components of solid rocket fuel or thermite (However, the oft-stated claim that the ship was "coated in rocket fuel" is a significant overstatement.)

Opponents of the IPT point out that cellulose acetate butyrate dope is rated within the plastics industry as combustible but nonflammable. It will burn when placed within a fire but will not readily ignite by itself. It is considered to be self-extinguishing. While the coating components were potentially reactive, they were not only in the wrong proportion, they were separated by a layer of material (cellulose acetate butyrate) that would have prevented their mingling and reaction.

Proponents of the IPT also point out that, after the disaster, the Zeppelin company's engineers determined this skin material, used only on the Hindenburg, was more flammable than the skin used on previous craft and changed the composition for future designs. Opponents of the IPT counter that Hindenburg had flown for over a year (and through several lightning storms) with no reports of adverse chemical reactions, much less fires on the fabric.

Proponents of the IPT also point to fact that the naturally odorless hydrogen gas in the Hindenburg was "odorised" with garlic so that any leaks could be detected, and that there were no reports of garlic odors during the flight or prior to the fire. Opponents of the flammable fabric theory point out that odorized hydrogen would only be detected in the area of a leak. The fire started near the ship's top, an area devoid of personnel. Since any leaking hydrogen would have moved upward, away from any personnel, there could possibly have been a hydrogen leak in the area where the fire started with no odor detected.

Proponents of the IPT point out that Hindenburg was also seen to stay aloft for a relatively long amount of time after the fire started, instead of immediately tilting and falling as it would have if the hydrogen cells were ruptured. Opponents of the IPT reply that any delay in the ship's descent was the result of buoyancy forces and their effect upon the inertia of the ship's considerable mass. The total event, initiation of the fire and its near total destruction upon the ground, took scarcely 37 seconds. According to opponents of the IPT, burning hydrogen alone can explain the event. [1]

Rate of flame propagation

Regardless of the source of ignition or the initial fuel for the fire, there remains a third point of controversy with regard to the cause of the rapid spread of the flames along the length of the ship. Here again the debate has centered on the culpability of fabric covering of the ship vs. the hydrogen used for buoyancy.

The proponents of the "flammable fabric" theory also contend that the fabric coatings were responsible for the rapid spread of the flames. They point out that hydrogen burns invisibly (emitting light in the UV range), so the visible flames (see photo) of the fire could not have been caused by the hydrogen gas. The motion picture films show downward burning.

Opponents of the "flammable fabric" theory point out that once the fire started, all of the components of the ship (fabric, gas, metal, etc.) burned. So, while it may be that the combustion of the metal and fabric changed the color of the flame, the presence of color does not imply that hydrogen did not also burn. Further, while all fires generally tend to burn upward, including hydrogen fires, the enormous radiant heat from the burning of all of the materials of the ship would have quickly led to ignition over the entire surface of the ship, thus explaining the downward propagation of the flames.

Further, the recent technical papers [2] point out that even if the ship had been coated with typical rocket fuel (as is often stated in the press), it would have taken many hours to burn — not the 37 seconds that it actually took.

Also, a set of modern [3] experiments that recreates the fabric and coating materials contradicts the "flammable fabric" theory. These experiments conclude that it would have taken about 40 hours for the Hindenburg to have burned if the fire had been driven by a fabric fire. These experiments, as well as other industrial tests of the coating materials, conclude that the covering materials were combustible but nonflammable. Two additional scientific papers [4] also strongly reject the "flammable fabric theory".

Cultural references

Audio

- The 1938 radio drama version of "War of the Worlds" uses the reporting of the Hindenburg disaster as inspiration for their style of reporting the Martian invasion.

- British hard rock group Led Zeppelin's eponymous first album has a picture of the Hindenburg disaster on the front cover. The band's name is a reference to Keith Moon's (of The Who) quotation that the band would "go over like a lead balloon"

- Mentioned in the Arrogant Worms song, "History Is Made By Stupid People".

Television

- A Two Pints of Lager and a Packet of Crisps episode has the character Johnny inflate a condom to impress Louise, he then pops the condom with a cigarette lighter before shouting 'It's the Hindenburg disaster - that's history! I am intelligent!', much to the disgust of Donna and Janet who call Johnny "insensitive".

- A DuckTales episode features a dirigible named "The Uncrashable Hindentanic," a spoof of the Hindenburg and the Titanic. Its voyage from Duckburg to London is an unqualified disaster. The Hindentanic catches on fire, blows up and crashes into an iceberg, ultimately sinking into the North Atlantic.

- A Saturday Night Live sketch from a season six episode (host: Robert Hays, musical guests: Joe "King" Carrasco and the Crowns and 14 Karat Soul) has Eddie Murphy as a professional "Space Invaders" player who shoots down a Goodyear Blimp, which sends sportscaster Joe Piscopo into a rant reminiscent of the Hindenburg disaster broadcast.

- In The Simpsons episode, "Bart the Fink" (where Krusty the Clown fakes his death in order to escape punishment for tax evasion), Bart Simpson opens a checking account and shows off his first checkbook, which features a flip book animation of the Hindenburg disaster. Briefly on the cover page, there is a bit of text that says "Herbert Morrison series—Oh the Humanity!"

- In another Simpsons episode, this time the season four episode, "Lisa the Beauty Queen", Barney Gumble rides a blimp that crashes into a radio tower like the Hindenburg during the opening of a Danish superstore. Kent Brockman (who is reporting live) shouts, "Oh, the humanity!" before announcing the opening of the "Severe Tire Damage" spikes by Amber Dempsey (the girl chosen as Little Miss Springfield before Lisa took over).

- Yet another Simpsons episode, "Marge vs. the Monorail", has a scene where celebrities are drinking at a bar on the new monorail and the opening shot shows a framed picture of the Hindenburg disaster.

- In "The Crest of Kindess" of Digimon Adventure 02 there is a scene where Ken's flying base (shaped like an airship) falls and hits the ground. As it does, one of the Digimon cries, "OH, the humanity!"

- A first season episode of WKRP in Cincinnati relates a disastrous Thanksgiving promotion, which includes Carlson dropping live turkeys out of a helicopter. The scene is reported live on the air by the station's news director, Les Nessman (Richard Sanders), breathlessly describing the unseen birds plummeting to the ground, in the same manner as Herbert Morrison's coverage of the Hindenburg disaster, “It's a helicopter, and it's coming this way. It's flying something behind it, I can't quite make it out, it is a large banner and it says, uh - Happy... Thaaaaanksss... giving! ... From ... W ... K ... R... P!! No parachutes yet. Can't be skydivers... I can't tell just yet what they are, but - Oh my God, they're turkeys!! Johnny, can you get this? Oh, they're plunging to the earth right in front of our eyes! One just went through the windshield of a parked car! Oh, the humanity! The turkeys are hitting the ground like sacks of wet cement! Not since the Hindenburg tragedy has there been anything like this!”

- In another Simpsons episode where Santa's Little Helper is now owned by Mr Burns, Burns shows the dog a film of what Dogs might find disturbing. One sketch is the Hindenburg disaster.

- In an episode of Family Guy when Peter and Lois try to get Cleveland and Loretta back together after an affair, Peter shouts "To the HindenPeter!" he runs outside and gets inside a Zeppelin with his face on the front of it. But the Zeppelin blows up and crashes on the Swanson lawn. This happened again earlier in the episode but with The Petecopter.

- In the episode of The Waltons titled "The Inferno" (10 Feb 1977), John-Boy is a witness to the Hindenberg crash. Shots of a horrified John Boy with bit of burning rubbish floating around him were inserted into the famous newsreel footage.

- On I Love the 70s: Volume Two comedians ponder what Goodyear was thinking when they launched the Goodyear Blimp. "Haven't we learned anything from a little thing called the Hindenburg?

Other

- In the Massive Multiplayer Online Role-playing Game (MMORPG) World of Warcraft, a non-playable character (NPC) named "Hin Denburg" operates the zeppelin traveling to Grom'Gol.

- In a Simpsons comic book, the Duff Blimp is shot at by police because it has the infamous El Barto (Bart Simpson) vandalising the side along with El Grampo (Abraham Simpson). The Blimp explodes, and Homer Simpson cries; "D'oh! the humanity!"

- A major part in The Never War (the Pendragon Series by D. J. MacHale centers around the Hindenburg; the main character must allow the disaster to happen to save the world from a Nazi conspiracy.

- The Hindenburg is the primary motif of the first section of Three Tales by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot.

- In the movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Indy secures a flight for his father and himself out of Germany on "the first flight they had". Ominous music then plays as we see that they're headed for a zeppelin flight. Though the ship's name is unstated, the year (around 1936-1937) and the music cue suggest that it is the Hindenburg. Indy and his father escape in a biplane, and the airship's fate is unknown.

- In the movie The Rocketeer, the Hindenburg's sister ship LZ 130 is destroyed on a secret mission over Hollywood. However its fictitious, strange enough name here is Luxembourg, not Graf Zeppelin II (Luxembourg had never been a German state and is spelled Luxemburg in German).

- The opening scene of the film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, which is set in 1939 (two years after the actual Hindenburg disaster) shows a zeppelin, named the Hindenburg III, docking at the mooring mast of the Empire State Building (which, in reality, was never put into function).

- When George W. Bush created the Department of Homeland Security, the media called it a rearrangement of the deck chairs on the Titanic. In 2006, Stephen Colbert, in his keynote address to the White House Correspondents' Association dinner, rebuked the media on that statement, saying, "This administration is not sinking. This administration is soaring. If anything, they are rearranging the deck chairs on the Hindenburg!"

- In the video game Timesplitters: Future Perfect a level on the Arcade mode is a Zeppelin and there is a picture of the Hindenburg flying next to the radio tower before it crashed.

- U.S. film star Jan Sterling was scheduled to take the doomed flight on the Hindenburg, but was turned away for having too much luggage.

See also

- Hindenburg Disaster Newsreel Footage

- Herbert Morrison

- The Hindenburg (1975 Movie)

- List of Airship Accidents

- Zeppelin

- Harold G. Dick was an American engineer who flew on most of the Hindenburg flights.

References

- Birchall, Frederick (August 1, 1936). "100,000 Hail Hitler; U.S. Athletes Avoid Nazi Salute to Him". The New York Times, p. 1.

- Duggan, John (2002). LZ 129 "Hindenburg" — The Complete Story. Ickenham, UK: Zeppelin Study Group. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9.

- ^ Source for the cause of death is secondary. Found on page 35 of Hawken, P, Lovins, A & Lovins H, 1999, "Natural Capitalism", Little Brown & Company, New York. Their footnote references Bain, A, 1997, "The Hindenberg Disaster: A Compelling Theory of Probable Cause and Effect", Procs. Natl. Hydr. Assn. 8th Ann. Hydrogen Mtg. (Alexandria, VA) March 11-13 pp. 125-128.

External links

- Video of the incident

- Page at Great Zeppelins website, with various pictures

- Complete passenger and crew listing

- Footage from Castle and Pathé coverage of the Hindenburg disaster

- An Article Supporting the Flammable Fabric Theory

- Two Articles Rejecting the Flammable Fabric Theory

- Experiments Reject the Flammable Fabric Theory

- FBI investigation into the Hindenburg disaster

- Harold G. Dick was an American engineer who flew on most Hindenburg flights.

- CD of the Hindenburg Disaster WLS news report

- Hindenburg Fire Video at Internet Archive

- "The Hindenburg" - Failure Magazine (January 2002)

- Hindenbush Created by a fan, inspired by Colbert's, "This administration is Soaring!" line from the 2006 White House Press Correspondents' Dinner

- Zeppelin Company -- the company is still in the airship business today