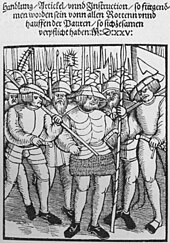

Twelve articles

The Twelve Articles (also: Twelve Articles of the Peasantry, Twelve Articles of the Peasantry in Swabia or 12 Articles of the Peasantry ) are among the demands made by the peasants in Memmingen in the German Peasants' War in 1525 against the Swabian Federation . According to the Magna Carta of 1215, they are considered to be one of the first written demands for human and civil liberties in Europe, and the assemblies leading to the Twelve Articles have been described as “a kind of constituent assembly ”, “which, if only in broad terms, attributed political power to certain institutions ”.

Happenings

On March 6, 1525, around 50 representatives of the Upper Swabian farmers' groups (the Baltringer Haufen , the Allgäuer Haufen and the Bodensee Haufen ) met in Memmingen to discuss how to act together towards the Swabian Federation . After difficult negotiations, one day later they announced the Christian Association of Peasants, also known as the Upper Swabian Confederation . On March 15 and 20, 1525, the farmers met again in Memmingen and, after further deliberations, passed the Twelve Articles and the Federal Order.

These two are the only ones of the many programs of the Peasant War that have been printed. The Twelve Articles in particular were printed within the next two months with a total of 25,000 copies, an enormous number for the time, and spread throughout the territory of the Holy Roman Empire . Since the two texts were not developed further during the peasant war, the historian Peter Blickle speaks of a “constituent peasant assembly” in Memmingen.

The Twelve Articles

One of the original documents of the twelve articles is kept in the Memmingen city archive. The following is a rough translation of the text of the Twelve Articles into today's German:

- Every congregation should have the right to choose its pastor and to disgust (dismiss) him if he behaves improperly. The pastor should preach the gospel loudly and clearly without any human additions, since the scriptures say that we can come to God only through true faith.

- The pastors are to be paid from the big tithe . Any surplus is to be used for village poverty and the payment of war tax. The little tithe is to be dismissed (given up) , since it was forged by men, because the Lord God created cattle for man freely.

- Has the custom so far been that we have been taken for own people (serfs) , which is to be merciful , seen that Christ has redeemed and bought us all with his precious bloodshed , the shepherd as well as the Most High, except none. That is why Scripture invents the fact that we are free and want to be.

- Is it unfraternal and contrary to the Word of God that the poor man should not have power to catch game, poultry and fish? For when the Lord God created man, he gave him power over all animals, the bird in the air and the fish in the water.

- Have the gentlemen appropriated the woods (forests) on their own. If the poor man needs something, he has to buy it for double the money. Therefore, all wood that has not been bought (meaning former community forests that many rulers had appropriated) should fall back to the community (be returned) so that everyone can meet their needs for construction and firewood from it.

- Should one have a fair understanding (rather reducing it) of the services (compulsory service) , which are increased from day to day and increase daily , how our parents served, solely according to the word of God.

- Should the rulers not increase the services of the peasants beyond the level fixed at the award. (An increase in the fron without an agreement was quite common.)

- Many goods can not bear the rent . Honorable people should inspect these goods and re-establish the validity according to equity, so that the farmer does not do his work in vain, because every day laborer is worthy of his wages.

- Are the great sacrilege (court fines) always made new statutes. One does not punish according to the form of the thing, but at will (increases in penalties and arbitrariness in the sentencing were common) . Is our opinion to punish ourselves with the old written punishment, according to which the matter has been dealt with, and not according to favor.

- Some have appropriated meadows and fields that belong to a community (common land that was originally available to all members) . We want to take them back to our common hands.

- Should the death (a kind of inheritance tax) be completely dismissed, and widows and orphans should never be robbed so shamefully against God and honor.

- Is our decision and final opinion, if one or more of the articles presented here were not in accordance with the word of God ..., we want to refrain from, if one explains it to us on the basis of the scriptures. If we were allowed to have a number of articles now and it would be found afterwards that they were wrong, they should be dead and gone from now on. But we also want to reserve ourselves the right to find more articles in Scripture that would be against God and a burden for one's neighbor.

The federal order

The federal system also achieved high editions and was probably popular with farmers mainly because it offered a model for a communal, federal social system. In the Black Forest , Alsace and Franconia , peasant communities can be identified that were organized accordingly.

Origin of the Twelve Articles

It is controversial who the Twelve Articles go back to. Some sources attribute it to the farmer's chancellor Wendel Hipler . As a rule, however, they are attributed to Sebastian Lotzer from Memmingen , who may have expanded existing texts together with the reformer Christoph Schappeler . Even Johann Hüglin was pulled as a helper when writing the article into consideration. At least his alleged assistance was one of the charges in his inquisition trial, which resulted in him being burned.

On February 16, 1525, about 25 villages belonging to Memmingen called for significant improvements in view of their economic situation and the general political situation at the city council. The complaints were summarized in the Memmingen articles . They touched on the corporal rule , the manorial rule , rights of use to the forest and the commons as well as church demands. The peasants wanted reform on a broad front. The city set up a committee of the villagers and counted on a long catalog of specific demands. Very unexpectedly, however, the peasants issued a uniform, fundamental declaration consisting of twelve articles. Many of these demands could not be enforced in the council, but it can be assumed that the articles of the Memmingen landscape were the basis for discussion of the twelve articles of the Upper Swabian Confederation of March 20, 1525.

It is quite possible that the demands of Joß Fritz , which he had made during the Bundschuh conspiracy in 1513, influenced the Articles of the Memmingen Landscape and thereby in turn the Twelve Articles themselves.

Luther and the Twelve Articles

The peasants bore heavily among the many burdens imposed on them, and saw in the standpoints of Luther and the Reformation that most of them were God's will not foreseen.

Luther, however, was not pleased with the uprisings of the peasants and their appeal to him. Possibly he saw harmful consequences for the cause of the Reformation in this. He turned to the peasantry and exhorted them to peace. He also wrote to the gentlemen :

“They made twelve articles, some of which are so righteous that they bring you to shame before God and the world. But they are almost all geared towards their use and their benefit and are not worked out in the best possible way. [...] Well in the long run it is unbearable to tax and harass people like that. "

In May 1525, Luther published Against the Murderous and Robbery Rotten der Bauern peasantry , in which he sided with the authorities and called on them to destroy the peasants out of concern for the God-ordained order. The specific reason for this was the bloody deed in Weinsberg , in which the farmers under Jäcklein Rohrbach killed the Obervogt Count Ludwig Helferich von Helfenstein and his followers after storming the town and castle of Weinsberg .

After-effects

The basic ideas laid down in the demands seem to have lasted much longer than their leading representatives and fighters.

A comparison with the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 shows some correspondences in the motifs and the implementation in the text. Parallels can also be found in the results of the French Revolution from 1789.

In the following three centuries of the early modern period , the farmers hardly revolted. It was only with the revolution of 1848/49 that the goals mentioned in the Twelve Articles of 1525 could be implemented.

literature

- Peter Blickle : Again on the genesis of the twelve articles. In the S. (Ed.): Bauer, Reich, Reformation. (= Festschrift for Günther Franz on his 80th birthday). Ulmer, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-8001-3057-2 , pp. 286-308.

- Peter Blickle: The Revolution of 1525. 4th revised and bibliographically expanded edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2004, ISBN 978-3-486-44264-9 .

- Peter Blickle: The history of the city of Memmingen. Volume 1: From the beginning to the end of the imperial city. Theiss, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-8062-1315-1 .

- Heinrich Böhmer: The origin of the twelve articles of the farmers from 1525. In: Leaves for Württemberg church history. New episode, 14th year. Stuttgart 1910, pp. 1–14 ( digitized version) and p. 97–118 ( digitized version ).

- Martin Brecht: The theological background of the twelve articles of the peasantry in Swabia from 1525. Christoph Schappeler's and Sebastian Lotzer's contribution to the peasant war. In: Heiko A. Obermann (Ed.): German Peasant War 1525 (= magazine for church history . Volume 85, issue 2). Kohlhammer, Stuttgart et al. 1974, ISSN 0044-2925 , pp. 30-64 (178-208).

- Günther Franz : The Origin of the "Twelve Articles" of the German peasantry. In: Archive for the history of the Reformation . Volume 36. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh 1939, ISSN 0003-9381 , pp. 195-213.

- Görge Knut Hasselhoff, David von Mayenburg (ed.): The twelve articles of 1525 and the “divine right” of the peasants - legal historical and theological dimensions. Ergon, Würzburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-89913-914-3 .

- David von Mayenburg: Common Man and Common Law. The twelve articles and rural law in the age of the Peasants' War . In: Studies on European Legal History . 1st edition. tape 311 . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-465-04333-1 (plus habilitation thesis, University of Bonn, 2012).

- Heide Ruszat-Ewig: The 12 Farmer's Articles . Pamphlet from 1525. Memmingen Historical Association, Memmingen 2018, ISBN 978-3-946241-10-2 .

- Günter Vogler: The revolutionary content and the spatial distribution of the Upper Swabian Twelve Articles. In: Peter Blickle (Ed.): Revolt and Revolution in Europe. (= Historical magazine. New series, supplement 4). Oldenbourg, Munich 1975, DNB 760044139 , pp. 206-231.

- Ernst Walder: The political content of the twelve articles of the German peasantry from 1525. In: Swiss contributions to general history. Volume 12. Lang, Bern 1954, ISSN 0080-7222 , pp. 5-22.

Web links

- Twelve articles in a facsimile in the Memmingen city archive

- Julia Huber: There is an origin of human rights in the Allgäu . In: Sueddeutsche.de , January 6, 2018

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Twelve Articles and Memmingen on memmingen.de. Retrieved March 11, 2009 (archive version of the website). The presentation on the website of the City of Memmingen is based on the speech by Johannes Rau at the Memmingen commemoration for the 475th anniversary of the writing of the Twelve Articles . - Peter Blickle: The history of the city of Memmingen, from the beginning to the end of the imperial city period. P. 393 ff .; Twelve articles and federal regulations for farmers, pamphlet “An die versamlung gemayner pawerschetzt”, Memmingen City Archives, materials on Memmingen's city history, Series A, Issue 2, pp. 1 and 3 ff .; Unterallgäu and Memmingen, Edition Bayern, House of Bavarian History, 2010, p. 60; Memmingen town law, statute of the town of Memmingen on the Memmingen Freedom Prize 1525, preamble.

- ↑ Federal Order of the Upper Swabian Farmers 1525. Accessed on May 16, 2020 .

- ↑ Peter Blickle: The history of the city of Memmingen, from the beginnings to the end of the imperial city period. Stuttgart 1997, p. 393.

- ↑ Julia Huber: The history of human rights also lies in the Allgäu. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. January 6, 2018, accessed June 17, 2020 .

- ↑ The full text after the facsimile can be found in: David von Mayenburg: Gemeiner Mann und Gemeines Recht. The twelve articles and rural law in the age of the Peasants' War . In: Studies on European Legal History . 1st edition. tape 311 . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-465-04333-1 , p. 365–372 (including habilitation thesis, University of Bonn, 2012).

- ↑ For large and small tithe see tithe rule .

- ↑ Georg Ernst Waldau : Materials on the history of the peasant war. Karl Gottlieb Hoffmann, Chemnitz 1791, p. 16 .