52nd Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony in C minor, Hoboken directory I: 52 wrote Joseph Haydn to the 1771st

General

The symphony No. 52, the autograph of which has not survived, was composed by Haydn around 1771 while he was employed as Kapellmeister by Prince Nikolaus I Esterházy.

“[The symphony contrasts] homophonic and contrapuntal drama [...]; the upgrading of the finale and its demarcation from the first movement through the counterpoint builds a bridge to the fugue finals in the string quartets op. 20, which was created a year later. "

"The symphony No. 52 is an extraordinary work, the expressive intensity of which at times equals the " farewell symphony " ."

To the music

Instrumentation: two oboes , two horns , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . At that time, a bassoon was used to reinforce the bass voice, even without separate notation . On the participation of a harpsichord - continuos are competing views in Haydn's symphonies. In some later sources an obligatory part is provided for the bassoon. Another special feature of the symphony is the constant change between horns in C in alto and bass register: In the first and last movements, both in C minor with longer passages also in E flat major, the 1st horn plays with a vocal arc in C ( Old position), the 2nd horn in Eb; whereas in the C major Andante and the C minor minuet (with trio in major) both horns play in C (bass range).

Performance time: approx. 20 to 25 minutes (depending on the tempo and adherence to the prescribed repetitions).

With the terms of the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this scheme was designed in the first half of the 19th century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to a work composed around 1771 with restrictions. The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

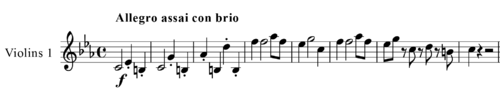

First movement: Allegro assai con brio

C minor, 4/4 time, 163 bars

The sentence is "characterized by sharp contrasts [...], jumps in tone, rhythmic contrasts and string tremolos". The first, asymmetrically structured, theme with a gloomy, impetuous character consists of a rising unison phrase in staccato and a "follow-up" with the first violin leading the voice. The unison head of the theme is repeated as a variant in the piano and with legato (instead of staccato) and merges seamlessly into the forte passage from bar 14. The continuous eighth note movement in the viola and bass creates a continuously pushing impulse. The passage is made up of three motifs (components): Motif 1 with upward scale and tone repetition ("scale motif"), motif 2 with upward intervals in full-bar notes ("interval motif ": two fourths and a seventh) and a descending tremolo sound surface in fortissimo.

The second theme (from bar 34, tonic parallel in E flat major) is only intended for strings in the piano and, thanks to its calmer character, contrasts strongly with the stormy events before. Characteristic are the tone repetitions in dotted rhythm and the movement interrupted by pauses. After five bars the whole orchestra unexpectedly breaks in with another forte block based on a variant of the scale motif. With a sweeping gesture, the 1st violin alone leads to a further appearance of the second theme, again in E flat major. Its second half is no longer "interrupted", instead it is extended as an "almost recitative resolution" in a hesitant gesture. The final group consists of an ascending, rhythmic triad motif.

The development begins with a contrasting change from the head of the second theme (piano) and the interval motif (forte, now as interval steps downwards and starting with the seventh). The interval motif is then picked up by the bass. This is followed by appearances by the heads of the first theme in F minor (from measure 82) and the second theme in A flat major (from measure 92). Further strong contrasts follow: variant of the scale motif (forte), chromatic upward sequencing of the head from the second theme (piano, strings only), scale motif (forte).

The recapitulation is different from the exposition: the first theme is not repeated. The transition to the second theme has been changed; the scale and interval motifs are missing. On the second appearance of the second theme, the delaying “recitative” is lengthened and the delay effect is reinforced: the music slows down and comes to a pianissimo stop before the final group finishes the movement in an energetic forte. The slowdown is a fully composed ritardando , an effect that Haydn uses here for the first time in a symphony. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

Second movement: Andante

C major, 3/8 time, 197 measures

The first theme of the “spacious” Andante gets a dance-like character through its alternation from legato and staccato as well as its rhythm, but after the dramatic first movement it seems almost a bit bland. The violins play (as in other slow movements of Haydn's symphonies from this period) with mutes. The upbeat thirty - second figure from measure 3 is essential for the theme and the entire rest of the movement . The theme consists of three parts: the main melody (measures 1 to 6), the continuing middle section (measures 6 to 16) and the final turn, which shortens the main melody picks up.

The transition to the second theme begins as a forte block of the whole orchestra in bar 21 and emphasizes the upbeat figure from the first theme as an energetic unison movement. What is striking are the dynamic contrasts between forte and piano with the "strange" E flat that suddenly bursts in twice, the subsequent accents on unstressed beat times and the use of chromatics . Another Fortepassage, which is formed from the opening motif, leads to the second topic.

The second “theme” (from measure 42, dominant in G major), like the first, is only played by the strings. With its tone repeater and the opening figure, it is related to the first theme and hardly contrasts with it. The use of chromatically falling lines is also striking in the second theme. The final group from bar 70 brings another variant of the material from the first topic.

After the appearance of the first theme in the dominant G major, the development merges into a longer, lively forte passage, where the opening figure alternates in unison (as from bar 21) with parallel guidance in the violins (similar to bar 38) . The second theme then establishes the tonic parallel in A minor for a few bars piano. Its downward chromatic line is now somewhat broader than in the exposition.

The recapitulation is similar to the exposition, but the winds are involved in the first theme, the middle part of the theme is extended, the third part is left out. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

Third movement: Menuetto. Allegretto

C minor, 3/4 time, with trio 60 bars

The minuet with its “gloomy and heavy” to “leaden” atmosphere is characterized by the use of chromatics, unusual intervals (diminished fourth, diminished third, excessive second), the sigh-like semitone steps and the alternation of forte and piano. The movement is predominantly two-part with parallel upper parts on the one hand (oboes, violins) and lower parts on the other (viola, bass). Due to the many upbeats, the dance character of the minuet takes a back seat, the minuet character becomes "strangely unstable". Despite the predominance of piano, the minuet "exerts an unpleasant compulsion."

The trio contrasts with the minuet through the key of C major, the solo oboes and the generally friendlier character. The opening motif is a variant of the beginning of the minuet. The semitone steps already present in the minuet with an accent on the actually unstressed third quarter of the bar now appear dominantly in energetic repetition.

Fourth movement: Presto

C minor, 2/2 time (alla breve), 188 measures

The first theme is only presented by the violins and bass piano. It is reminiscent of the beginning of a fugue: the 1st violin begins, accompanied only by the 2nd violin as a counterpoint. In bar 13, both violins repeat the theme an octave lower in parallel, while the bass plays the previous counterpoint. The second half of the topic is somewhat varied. With its semitones and syncopations, the theme is reminiscent of the minuet. Without a caesura and continuing in the piano, the second theme follows from bar 30 in E flat major with voice guidance in the 1st violin, while the other strings (now also with viola) accompany. The theme consists of two four-bar halves. Each half is repeated as a decorated variant.

Only in bar 46 does the whole orchestra begin as a stormy forte block with continuous eighth notes and tremolo of the violins. This dramatic outburst lasts until the end of the exposure, at the end with large leaps in intervals.

The development begins with the complete second theme in A flat major and then processes the first theme including counterpoint from bar 93. Surprisingly, Haydn switched on a pianissimo passage with the first theme in C minor (from bar 101), which can also be heard as the beginning of a reprise, but which is then followed by further development work. From bar 130 the long, stormy Forte section from the exposition follows as a variant. It ends on a dissonant chord, where the music interrupts in an extended general pause. Only then is the second topic "submitted" in the tonic. This structural arrangement conceals the beginning of the reprise: the half of the sentence “is an amazing example of a merged development and recapitulation”.

Haydn also designed the coda-like end of the sentence in an unusual way: after energetic chord strikes "which culminate in a shocking 'stylish' beat", the rapid eighth note chains from the previous forte block - now fortissimo - end the movement.

According to Walter Lessing, "a peculiar, almost dogged restlessness [...] meets this finale, sometimes mysteriously oppressive [...], sometimes in violent, dismaying outbursts." Howard Chandler Robbins Landon calls the sentence a "grim tour-de-force" and the “Grandfather of Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. ” Peter Brown, on the other hand, finds the corner movements of Symphony No. 44 to be more successful.

See also

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 52nd Symphony from the “Haydn 100 & 7” project of the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 52 in C minor. Philharmonia No. 752, Universal Edition, Vienna. Series: Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (ed.): Critical edition of all symphonies (pocket score)

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 52 in C minor. Ernst Eulenburg-Verlag No. 565, London / Zurich (pocket score)

- 52nd Symphony (Haydn) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Andreas Friesenhagen, Ulrich Wilker: Symphonies around 1770–1774. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Row I, Volume 5b. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 2013, ISMN 979-0-2018-5044-3, 270 pp.

Individual references, comments

- ^ Anthony van Hoboken: Joseph Haydn. Thematic-bibliographical catalog raisonné, Volume I. Schott-Verlag, Mainz 1957, p. 65.

- ↑ Information page of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ a b Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , p. 272

- ↑ a b c d James Webster: Hob.I: 52 Symphony in C minor . Information text on Symphony No. 52 by Joseph Haydn of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ↑ James Webster: The Symphony with Joseph Haydn. Episode 7: Hob.I: 45, 46, 47, 51, 52 and 64. haydn107.com , accessed June 13, 2013.

- ^ A b Michael Walter: Symphonies. In Armin Raab, Christine Siegert, Wolfram Steinbeck (eds.): The Haydn Lexicon. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2010, ISBN 978-3-89007-557-0 , p. 698.

- ↑ Similar beginnings in unison for Symphonies No. 78 and No. 95, also in C minor .

- ↑ According to Ludwig Finscher (2000, p. 272) this resolution is reminiscent of the recitative passage in the first movement of the G minor string quartet opus 20.

- ^ A b c d e f g Walter Lessing: The symphonies of Joseph Haydn, in addition: all masses. A series of broadcasts on Südwestfunk Baden-Baden 1987-89, published by Südwestfunk Baden-Baden in 3 volumes. Volume 2, Baden-Baden 1989, pp. 55-57.

- ^ HC Robbins Landon : The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. Universal Edition & Rocklife, London 1955, p. 324.

- ↑ Robbins Landon (1955, p. 336): "The slow movement, especially, seems somewhat insipid (fad, scarf) after the violent Allegro assai (e) con brio."

- ^ HC Robbins Landon , quoted in Walter Lessing (1989 p. 56).

- ^ Howard Chandler Robbins Landon: Haydn: Chronicle and works. Haydn at Eszterháza 1766 - 1790. Thames and Hudson, London 1978, p. 298.

- ↑ "This is the grand-father of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, also created with mathematical and economic precision (especially the first movement)."

- ^ A. Peter Brown ( The Symphonic Repertoire. Volume II. The First Golden Age of the Vienese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis 2002, ISBN 0-253-33487-X ; p . 128): "In contrast, I find that this movement has many of the same flaws as the first. While this piece does have dramatic gestures, they do not measure up tho the tight argument seen in Symphony No. 44 (...) / 4. "