76th Symphony (Haydn)

The Symphony no. 76 in E flat major composed Joseph Haydn probably in 1782.

Composition of the symphonies No. 76, 77 and 78

Haydn probably composed the symphonies No. 76, 77 and 78 in 1782 during his employment as Kapellmeister to Prince Nikolaus I Esterházy . Its creation is probably related to the efforts of Willoughby Berties to win Haydn for his “Hanover Square Grand Concerts”. The trip to England did not materialize, however, probably because Haydn canceled due to his obligations in Esterházy or because Prince Nikolaus refused to give his consent. In a letter dated July 15, 1783, Haydn replied to Boyer's offer to sell him some works:

"High, and well bored,

especially high honored gentleman!

(…) I doubt whether I will be able to contenir you here for the following reasons: Firstly, I am not allowed to send any of my own handwriting contracts that I made with my prince out of the country, because he keeps them himself. I could put a piece twice in the score, but for that the time is too short for me, and I also find no sufficient reason for the fact that when a piece is copied cleanly and correctly, it is at least subject to the engraving more quickly. Secondly, one must judge my integrity, and not believe the paper:

last year I composed 3 beautiful, magnificent and not too long symphonies consisting of 2 violins, viola, basso, 2 corni, 2 oboe, 1 bass, and 1 bassoon, but everything very easy, and without much concertante ... "

Haydn was evidently by now practiced in dealing with publishers, “sometimes looking for his advantage a little bit unscrupulously”: At first he deliberately hesitated a little and even invoked a contract with the prince, which allegedly forbade him to export his works abroad send. At that time, Haydn already had a solid business relationship with the publishers Artaria in Vienna and Forster in London. Haydn then offered Boyer the three symphonies he had written in 1782 (nos. 76 to 78), albeit with the note that one should believe one's "righteousness and not the paper" (i.e. Haydn did not want to sign a contract). This caution seemed advisable to him because he had sold the three symphonies to two other publishers at about the same time: Torricella in Vienna and Forster in London. The works were published there in 1784, then by Boyer in 1785. Haydn has therefore given at least three “authentic” copies from his hand. Furthermore, the works were copied illegally (as was not unusual at the time). Writes Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in his letter to his father dated 15 May 1784 "... I know quite reliably Hofstetter of Haydn Musique Dopelt copiert - I have his newest three symphonies really."

“It was the first three symphonies that Haydn wrote directly for the market, and they were the debut of a clever and occasionally a little unscrupulous businessman. The game was repeated in the three following works, I: 79 – I: 81 (...). "

The symphonies were very popular among contemporaries and received good reviews. They are “technically demanding, but forego virtuosity, and they are also 'light' in the sense that they are extremely witty and subtle, but also a lot for the superficially listening thanks to all sorts of effects and simple, 'popular' tones Provide entertainment. (…) It is quite obvious that the composer is preparing himself here - also - for a large audience stratified according to musical level of education and listening expectations. ”Peter A. Brown speculates that Haydn might be able to design the symphonies to Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, who were extremely popular in London at the time.

In the trio of his fourth symphony in E flat major from 1972, Robert Simpson quotes a motif with dotted rhythm from the beginning of the first movement of Symphony No. 76.

To the music

Instrumentation: flute , two oboes , two bassoons , two horns , two violins , viola , cello , double bass . On the participation of a harpsichord - continuos are competing views in Haydn's symphonies.

Performance time: approx. 22 minutes.

With the terms of the sonata form used here, it should be noted that this scheme was designed in the first half of the 19th century (see there) and can therefore only be transferred to Symphony No. 76 with restrictions. - The description and structure of the sentences given here is to be understood as a suggestion. Depending on the point of view, other delimitations and interpretations are also possible.

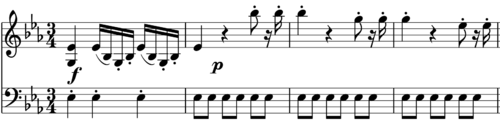

First movement: Allegro

E flat major, 3/4 time, 189 bars

Haydn opens the symphony by alternating motifs that contrast with one another (contrasting theme): the beginning forte motif with four chord hits on E-flat (hereinafter: opening motif, the violins resolve the second and third chord beats as a broken triad) is a six-bar piano - Movement in a falling line with dotted rhythm against (in the following: dotted motif). Within the dotted motif there is a change from staccato to legato , and the falling line in the violins is juxtaposed with a rising bassoon line. The opening motif is repeated with continued spinning up to bar 18. Here the movement on the dominant B flat major comes to a standstill, before the entire first theme (opening motif + dotted motif) is played again.

“The detailed analysis shows how Haydn enriches an apparently harmless topic with targeted musical impulses that activate the listener because his listening focus has to change several times. Even in the first bar it is unclear whether the violin sixteenth notes or the quarter chords are the main musical event. The apparent relaxation in bars 2 and 3 due to the uncomplicated conditions that occur there is followed by a change that forces the listener to pursue the formulation of the postscript in the first violin. At the same time, however, he is forced to understand the new articulatory element of the legato bow and the associated change through the addition of the bassoon timbre. How the listener orients his listening focus, whether he is mistaken for legato development and first violin at the same time, or whether he neglects one of the two in favor of the other, is up to him. But he has to make an - unconscious - decision because he cannot escape the hearing process. And the repetition of the first part is also gaining interest because the listening focus can now concentrate on the elements that were neglected during the first listening. "

Unexpectedly, the first appearance of the second, vocal theme follows pianissimo with a calm arc-like quarter movement in the tonic in E flat major. This appearance is over in bar 34, and after a short pause a new section follows abruptly, which contains not only runs in the forte but also the dotted motif. The harmonies change from C minor to B major to F major. From bars 45 to 65, the second theme then has its second appearance, now in the dominant B flat major and with a different ending. The final section of the exposition (bars 66–80) is characterized both by unison movements (runs and chromatic staccato movements) and by a reversal of the opening motif.

The implementation (clock 81-126) deals with more "melodic development" as with processing of material exposure. It begins with the unison running motif from the final section of the exposition. First in C minor, then the harmony changes with the second theme in C major. The still flowing movement comes to a halt (bar 91), the dotted motif leads briefly into the subdominant A flat major, on which the movement comes to rest again, before it becomes a little stronger again with the arc-like quarter movement from the second theme. In bar 113, C major is reached again, which after another pause leads to the F minor breakout with the unison movement. The transition to the recapitulation follows via an organ point-like section with an extensive tremolo .

The recapitulation is structured similarly to the exposition. However, the second theme appears only once - in the usual place - the work with the dotted motif is reinforced and the section with the unison movement is somewhat longer. The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

Second movement: Adagio, ma non troppo

B flat major, 2/4 time, 132 bars

The following structure is suggested for the sentence:

- Part A: bars 1 to 28, B flat major, piano. Presentation of the main vocal theme (1st violin headed “cantabile”) in the strings, chamber music or “violin concert-like” character. Repetition of the main theme with decorations; entire section is repeated.

- Part B1: bars 29 - 36, B flat minor, piano. Entire orchestra, tremolo-like carpet of sound with plaintive wind melody (oboe dominates). Section is repeated.

- Part B2: bars 37-52, B flat minor, continuation of B1, increase to fortissimo.

- Part A, variant 1: bars 53-80, B flat major, piano. Only strings, chamber music-like character, many triplets and sextoles.

- Part C1: bars 81–88, G minor, continuous thirty-second movement in fortissimo, “staccato assai”. Section is repeated.

- Part C2: bars 89–96, continuation of C1. B major, F major, C minor, tapering to alternation in G minor and D major.

- Part A, variant 2: bars 97-132, e.g. T. entire orchestra, solo cadenza of the 1st violin, bars 116–119, from bar 122 unison movement of the strings with bassoon in forte, end of movement with breath in pianissimo.

According to Howard Chandler Robbins Landon (1955), the dark minor passages with their modulations often achieve " Schubertian delicacy".

"The drastic confrontation of the melodically simple but sonically" thin "sections with sonically" thick "but melodically uncharacteristic sections corresponds in an exemplary way to what the 18th century understood as" humor "."

Third movement: Menuet. Allegretto

E flat major, 3/4 time, with trio 50 bars

The folk, somewhat melancholy melody interrupted by pauses is carried by the flute, the oboes and the first violin. The middle section changes to F minor, and Ludwig Finscher (2000) speaks of a “serious tone” in the minuet that contrasts with the very dance-like trio. This is also in an E flat major and, like the minuet, has a memorable, song-like melody that is reminiscent of “Schubertsche Länders ”. In addition to the 1st violin, the leading parts are flute and bassoon (both titled “Solo”). In the trio, the entire orchestra is involved; it does not contain concertante solos - as is often the case with Haydn - (flute and bassoon are titled solo, but do not have a concertante effect, but only lead the melody).

Fourth movement: Finale. Allegro, ma non troppo

E flat major, 2/2 time (alla breve), 161 measures

The whole movement is based on material from his singing, dancing melody with characteristic suggestions. The two four-bar halves of the theme are presented up to bar 24 only by the flute and 1st violin - piano accompanied by the other strings - in a repeated sequence (scheme: half 1 - 1 - 2 - 1 - 2 - 1), which is something at the beginning of a rondo . In bar 25 the timbre changes through the use of the entire orchestra in the forte with tremolo on E flat in the bass. From bar 37, the staggered head of the theme follows briefly, before from bar 41 the final group follows with characteristic octave jumps in eighth notes and striding bass movements in quarters. After an organ point on B below the subject's head, the exposition ends “open” on the B flat major seventh chord.

The development processes the motifs of the first half of the topic and offers the listener several surprises: After the short simple cadence that changes to C minor, the movement stops again, then tries a new "start" in A flat major, but breaks again and goes into strong quarter beats. This is followed by the section already known from the exhibition, with the motif staggered from the top of the topic. From bars 75 to 87, on the other hand, a motif from the end of the first half of the theme dominates, which is vigorously repeated and creates a monotonous soundscape, but which is changed somewhat harmoniously in each bar. Measure 89 ff. Then take up the head of the topic in staggered use. A final turn is then announced quite abruptly, but this leads to the fallacy in bar 97 with fermata (G major - seventh chord). The first half of the theme tries again to start again in C major, but breaks off - as at the beginning of the development. The second attempt in E flat major, on the other hand, is successful and ultimately turns out to be a recapitulation (bars 100 ff.). This is structured similar to the exposure. After the organ point, however, it shows an extended final section with the motif from the end of the first half of the theme, which can be viewed as a coda . The exposition, development and recapitulation are repeated.

Individual references, comments

- ↑ Information page of the Haydn Festival Eisenstadt, see under web links.

- ↑ a b c d Michael Walter: Haydn's symphonies. A musical factory guide. CH Beck-Verlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-44813-3 , p. 74 ff.

- ^ A b c d e Walter Lessing: The Symphonies by Joseph Haydn, in addition: all masses. A series of broadcasts on Südwestfunk Baden-Baden 1987-89, published by Südwestfunk Baden-Baden in 3 volumes. Volume 2, Baden-Baden 1989, pp. 211-214.

- ↑ a b c d e Ludwig Finscher: Joseph Haydn and his time . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-921518-94-6 , p. 309 ff.

- ^ Howard Chandler Robbins Landon: The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn. Universal Edition & Rocklife, London 1955, p. 389 ff.

- ^ Peter A. Brown: The Symphonic Repertoire, Vol. II. The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 2002, ISBN 0-253-33487-X , pp. 195 ff.

- ^ A b Anthony Hodgson: The Music of Joseph Haydn: The Symphonies. The Tantivy Press, London 1976, p. 103.

- ↑ Examples: a) James Webster: On the Absence of Keyboard Continuo in Haydn's Symphonies. In: Early Music Volume 18 No. 4, 1990, pp. 599-608); b) Hartmut Haenchen : Haydn, Joseph: Haydn's orchestra and the harpsichord question in the early symphonies. Booklet text for the recordings of the early Haydn symphonies. , online (accessed June 26, 2019), to: H. Haenchen: Early Haydn Symphonies , Berlin Classics, 1988–1990, cassette with 18 symphonies; c) Jamie James: He'd Rather Fight Than Use Keyboard In His Haydn Series . In: New York Times , October 2, 1994 (accessed June 25, 2019; showing various positions by Roy Goodman , Christopher Hogwood , HC Robbins Landon and James Webster). Most orchestras with modern instruments currently (as of 2019) do not use a harpsichord continuo. Recordings with harpsichord continuo exist. a. by: Trevor Pinnock ( Sturm und Drang symphonies , archive, 1989/90); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (No. 6-8, Das Alte Werk, 1990); Sigiswald Kuijken (including Paris and London symphonies ; Virgin, 1988-1995); Roy Goodman (e.g. Nos. 1-25, 70-78; Hyperion, 2002).

- ↑ a b The repetitions of the parts of the sentence are not kept in some recordings.

- ↑ Or, according to Walter 2007, can also be interpreted as a variant of the B part.

- ^ Robbins Landon (1955, p. 391): "The slow movement of No. 76, with its sombre passages in the minor and its curiously moving modulations, often approaches a Schubertian subtlety. "

- ↑ Michael Walter (2007) discusses the main melody of the movement as an example of irony in Haydn's music.

Web links, notes

- Recordings and information on Haydn's 76th Symphony from the “Haydn 100 & 7” project of the Eisenstadt Haydn Festival

- Thread on Symphony No. 76 by Joseph Haydn in the Tamino Klassikforum

- Joseph Haydn: Sinfonia No. 76 in E flat major. Philharmonia No. 776, Universal Edition, Vienna 1965, series: Howard Chandler Robins Landon (ed.): Critical edition of all of Joseph Haydn's symphonies. Pp. 101-149.

- Symphony No. 76 by Joseph Haydn : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- Sonja Gerlach, Sterling E. Murray: Symphonies 1782–1784. In: Joseph Haydn Institute Cologne (ed.): Joseph Haydn works. Series I, Volume 11. G. Henle-Verlag, Munich 2003.